INNOVATIVE FINANCING

FOR DEVELOPMENT:

Scalable Business Models that

Produce Economic, Social, and

Environmental Outcomes

September 2014

Innovative Financing Initiative

An initiative of the Global

Development Incubator

www.globaldevincubator.org

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study builds on the existing knowledge and research

of many financing and development experts from the public

and private sectors. The findings and analysis in the pages

that follow would not have been possible without the indi-

viduals from more than 50 organizations who shared data,

insights, and perspectives.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the

sponsors of this work—the Citi Foundation and the Agence

Française de Développement (AFD)—for their support

and financing.

The authors would also like to thank the members of the

project’s advisory committee. Specifically, we would like to

acknowledge Graham Macmillan and Hui Wen Chan from

Citi Foundation, Agnès Biscaglia from AFD, Andrew Stern

and Alice Gugelev from the Global Development Incubator,

and Henrik Skovby from Dalberg Group. Their generous

contribution of time, direction, and energy has been vital to

the success of this research.

This study was authored by Dr. Serena Guarnaschelli, Sam

Lampert, Ellie Marsh, and Lucy Johnson of Dalberg Global

Development Advisors, in collaboration with Sara Wallace,

who provided editorial expertise.

This is an independently drafted report and so all views ex-

pressed are those of Dalberg Global Development Advisors

and do not necessarily represent the views of the report’s

sponsors. Although the authors have made every effort to

ensure that the information in this report was correct at

time of print, Dalberg Global Development Advisors does

not assume and hereby disclaims any liability for the accu-

racy of the data, or any consequence of its use.

i

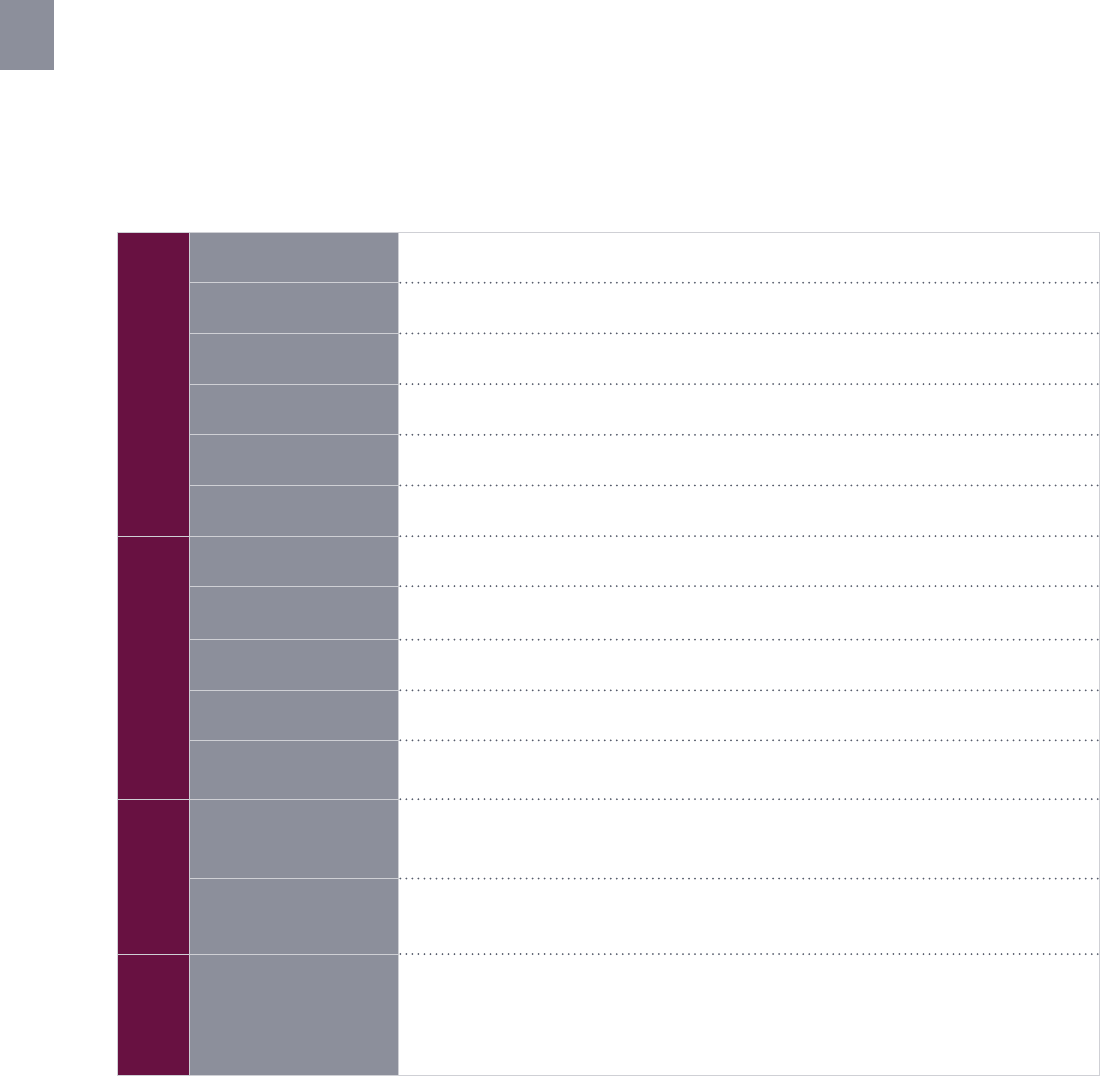

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................. iii

Introduction: The Unrealized Potential Of Innovative Financing ....................................................................................... v

Chapter 1: What Is Innovative Financing? ........................................................................................................................... 1

Definition .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1

Market Overview ................................................................................................................................................................. 3

Trends And Evolutions Of Innovative Financing Mechanisms ............................................................................................. 7

Chapter 2: How Does Innovative Financing Create Value? ...............................................................................................10

Outcomes For Consumers And Private Companies ............................................................................................................10

Outcomes For National Governments ............................................................................................................................... 12

Outcomes For International Donors ................................................................................................................................... 18

Chapter 3: What Are The Next Steps For Innovative Financing? ..................................................................................... 20

Opportunities ..................................................................................................................................................................... 20

Constraints ......................................................................................................................................................................... 21

Proposed Solutions And Roles For Different Actors ........................................................................................................... 23

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................................... 25

Annex 1: Methodology And Definitions ............................................................................................................................ 26

Annex 2: Selected References ........................................................................................................................................... 30

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomesii

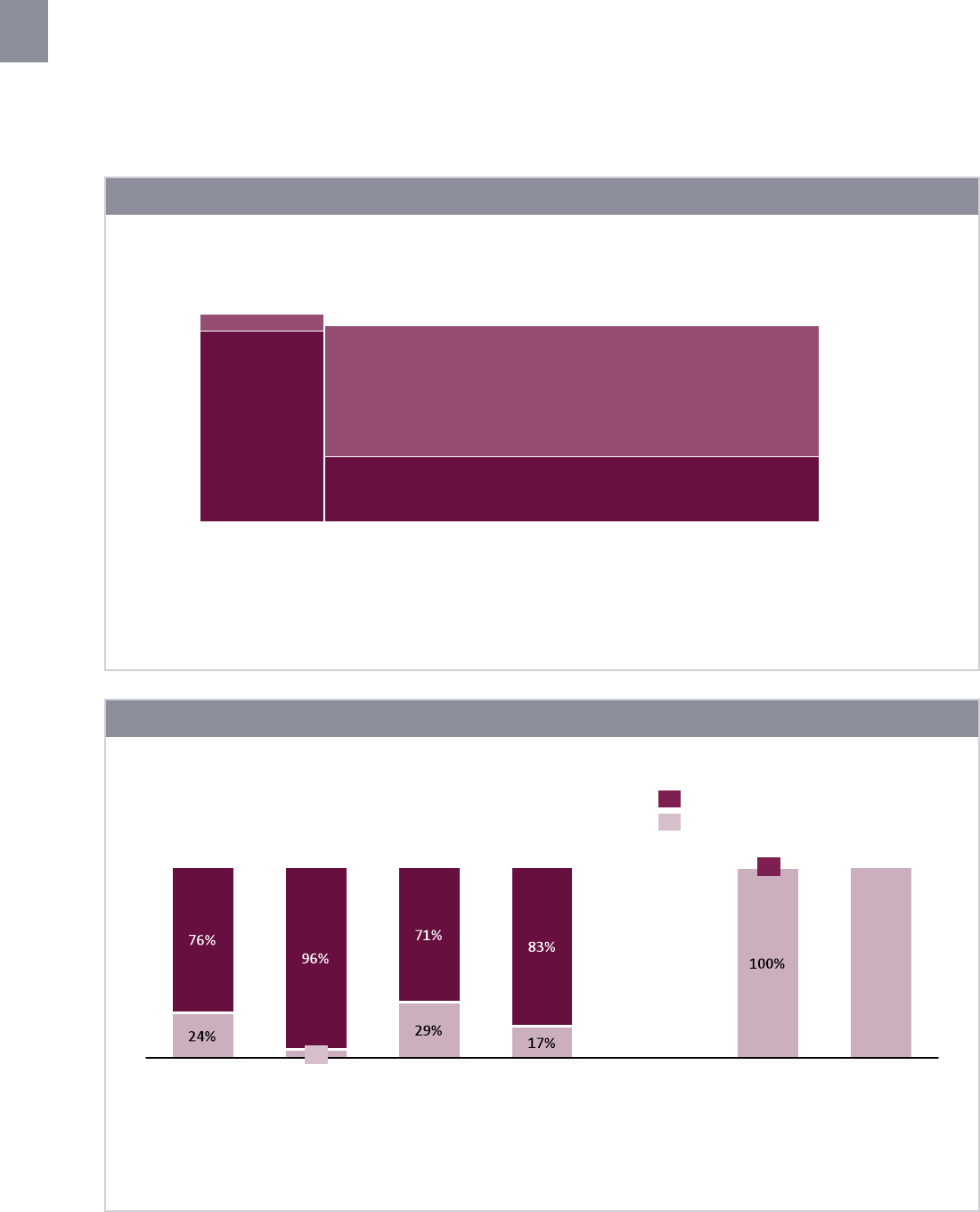

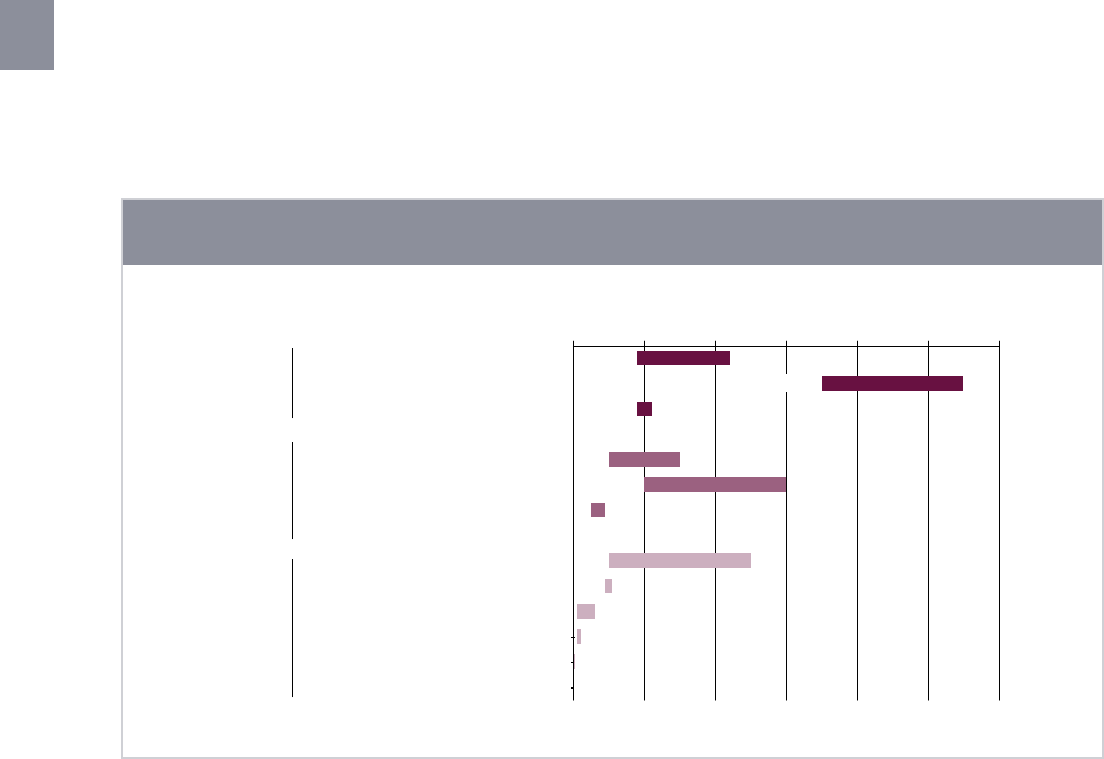

Figure 1: A successful transition to sustainable development will require substantial resources ......................................... vi

Figure 2: Innovative financing is a small component of public assistance............................................................................. vii

Figure 3: Innovative financing instruments introduce new products, expand into new markets, and attract

new participants ........................................................................................................................................................ 2

Figure 4: Bonds and guarantees are the largest innovative financing mechanisms ................................................................ 4

Figure 5: Innovative financing mechanisms have focused on a range of development challenges ......................................... 5

Figure 6: Most innovative financing mechanisms support transfers between the public and private sectors ........................ 6

Figure 7: The majority of instruments target risk-adjusted market returns .............................................................................. 6

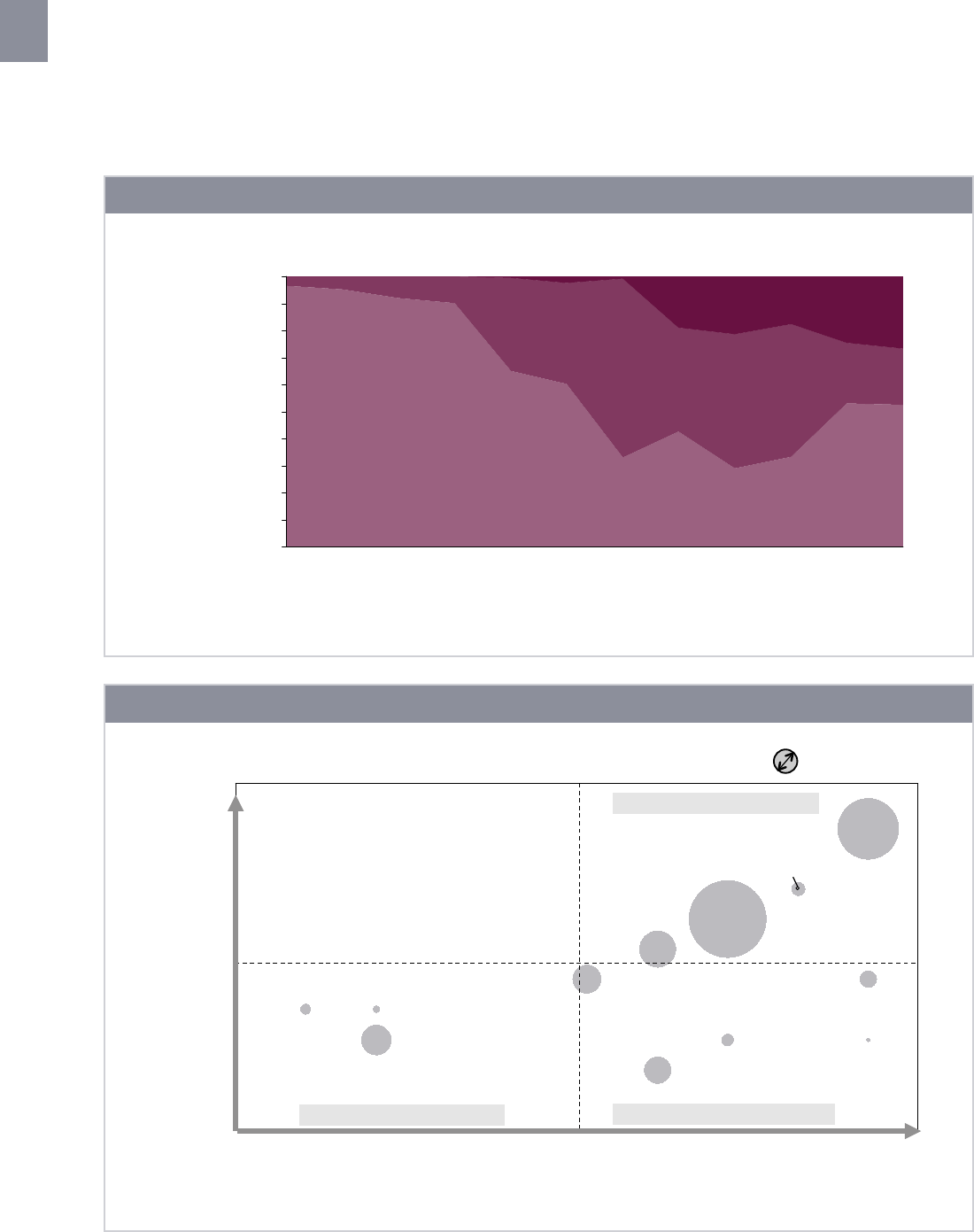

Figure 8: Innovative financing has grown through the introduction of new instruments ........................................................ 7

Figure 9: Innovative financing increasingly targets market returns ......................................................................................... 8

Figure 10: Established instruments rely on standards and mobilize more resources .............................................................. 8

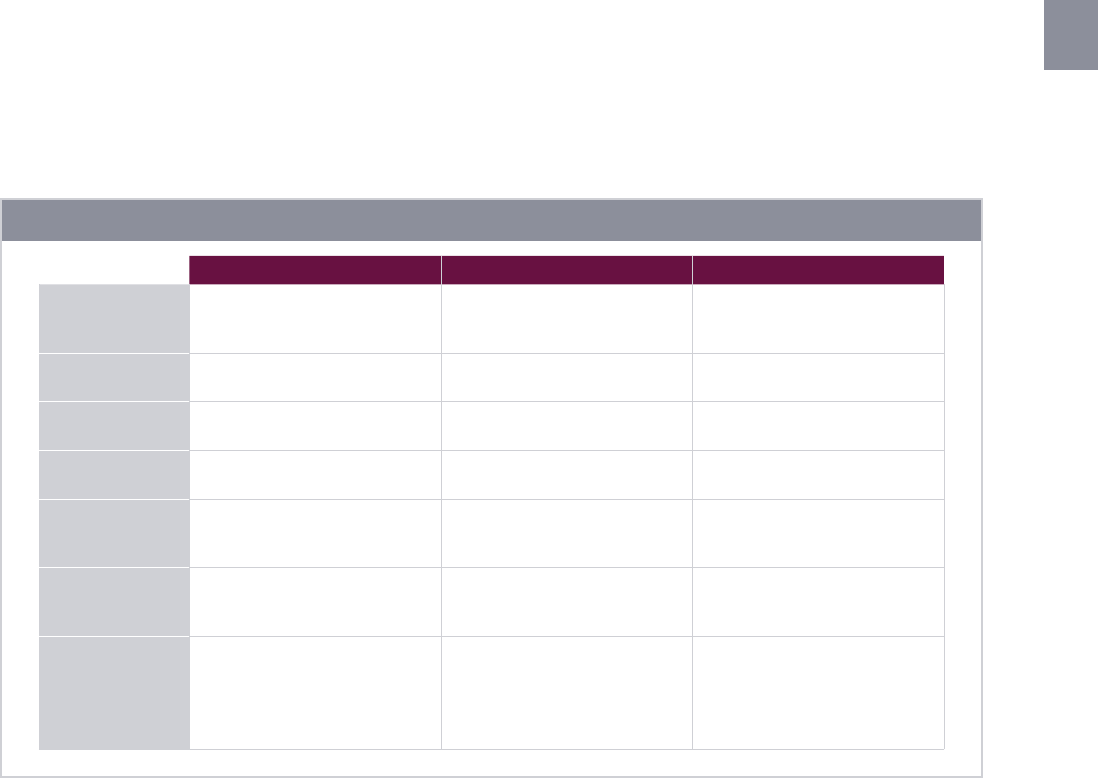

Figure 11: Innovative financing instruments produce a range of outcomes ...........................................................................11

Figure 12: The market for green bonds is growing ................................................................................................................ 13

Figure 13: Impact investing focuses on social sectors .......................................................................................................... 15

Figure 14: MIGA exposure has shifted to Sub-Saharan Africa ............................................................................................... 16

Figure 15: Political risk is perceived as a barrier to investment and demand for investment insurance is growing ............... 17

Figure 16: Long-term political risk insurance is becoming more widely available .................................................................. 17

Figure 17: Illustrative cash flows of a Development Impact Bond ......................................................................................... 19

Figure 18: The focus of innovative financing is changing ....................................................................................................... 21

Figure 19: Innovative financing mechanisms are projected to mobilize $24 billion per year by 2020 based

on historical performance ...................................................................................................................................... 22

LIST OF FIGURES

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii

Innovative financing is the manifestation of two impor-

tant trends in international development: an increased

focus on programs that deliver results and a desire to

support collaboration between the public and private

sector. Innovative financing instruments complement

traditional international resource flows—such as aid, foreign

direct investment, and remittances—to mobilize additional

resources for development and address specific market

failures and institutional barriers. Innovative financing is

an essential tool as the development community strives

to eliminate poverty, raise living standards, and protect

the environment.

This report aims to accelerate the growth of innovative

finance by creating a common language and vision for

leaders in both the public and private sector to use as

they explore innovative financing opportunities. Thus

far, a lack of clarity about what innovative financing is and

how standards can help compare the performance of dif-

ferent mechanisms has inhibited broader participation in

the sector and increased transaction costs associated with

the creation of new products. We believe that this report

can help by creating a common understanding of innova-

tive financing, providing an overview of the market, and

identifying opportunities for public and private sector actors

to make innovative financing commitments.

Innovative finance is not financial innovation. It encom-

passes a broad range of financial instruments and assets

including securities and derivatives, results-based financing,

and voluntary or compulsory contributions—all of which

this report explores in more detail. Established financial

instruments, such as guarantees and bonds, constitute

nearly 65% of the innovative financing market; while new

products dominate many conversations about innovative

financing, most resources mobilized through innovative

financing use existing products in new markets, or involve

new investors. Our definition of the “innovation” aspect of

innovative financing includes the introduction of new prod-

ucts, the extension of existing products to new markets,

and the presence of new types of investors.

Within this broad definition, innovative financing

has mobilized nearly $100 billion and grown by ap-

proximately 11% per year between 2001 and 2013. This

growth reflects the emergence of results-based financing

as an important tool for achieving development outcomes

and the capability of instruments such as bonds and invest-

ment funds to provide risk-adjusted returns for private

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomesiv

investors. Innovative financing instruments are emerging in

a variety of additional development areas—a few examples

include low-carbon infrastructure, mechanisms to improve

access to finance, and tools to reduce the cost of life-sav-

ing commodities.

Successful innovative financing instruments address

a specific market failure, catalyze political momentum

to increase and coordinate the resources of multiple

governments, and offer contractual certainty to inves-

tors. Often, innovative financing instruments reallocate

risks from investors to institutions better positioned to

bear the risk and, in the process, enable participation from

mainstream investors. Instruments that have mobilized

significant resources benefit from relatively simple financial

structures and a proven track record that clearly describes

the financial and social returns for investors.

The focus of innovative financing is shifting from the

mobilization of resources through innovative fundrais-

ing approaches to the delivery of positive social and

environmental outcomes through market-based instru-

ments. We anticipate three primary drivers of growth in the

innovative financing sector:

• Increased use of established financial instruments.

Established instruments that investors can evaluate

through existing risk frameworks, such as green bonds,

will attract new participants including pension funds

and institutional investors. Channeling the proceeds of

these instruments to productive development goals will

require new standards that specify how funds can be

used most effectively.

• Expansion into new markets through growth of repli-

cable products. Over the past ten years, the interna-

tional development community has experimented with

new instruments such as performance-based contracts.

These instruments do not yet have the track record

to attract institutional investors, but offer promising

opportunities to improve development outcomes in

new sectors.

• Creation of new innovative financing products. Finally,

we have seen the emergence of new products that are

theoretically promising, but have not yet demonstrated

results. While these products will remain a small portion

of the market in the short-term, we encourage donor

governments and other funders to continue experiment-

ing with these products so they can mature into the

next important asset class.

This report is the cornerstone of the Innovative Financing

Initiative, a coordinated effort led by public and private

institutions to facilitate more efficient markets by providing

performance data on past investments, catalyzing invest-

ments through engagement with new actors, and develop-

ing and promoting new products through work with leading

international development organizations. Building on past

efforts to describe innovative finance schemes, we identify

common characteristics of different initiatives, assess the

market demand for new models, and propose mechanisms

that can unlock the sector’s potential. These proposed

mechanisms include an innovative financing exchange to

provide performance data and technical assistance, a mar-

keting facility to expand the reach of established products,

and an incubator to reduce the costs associated with creat-

ing new instruments.

The future we want—a future that meets the needs of

people and the planet—will require an estimated trillions of

dollars in investment over the next ten years. We will need

to harness all possible sources of financing to address

global economic, social, and environmental challenges.

We hope to explore existing questions and promote new

solutions with our partners, expert advisors, and other par-

ticipants. If you are interested in joining the conversation,

please contact us at innovativefinance@dalberg.com. We

look forward to talking with you.

INTRODUCTION: The Unrealized Potential Of Innovative Financing v

INTRODUCTION:

The Unrealized Potential of Innovative Financing

The public sector will require trillions of dollars in capi-

tal and significant expertise from the private sector to

meet development objectives. The initial investments and

ongoing costs needed to eradicate poverty, provide public

goods (such as health and education), and manage the

natural resource base for economic and social development

will cost an estimated one trillion dollars per year or more.

1

Mitigating the effects of climate change and adapting to

new climate realities will also require hundreds of billions

of dollars. Resources required to achieve milestones set

out by development agendas, including the Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs) and their post-2015 successor,

the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), will be lower

than costs associated with adapting to and mitigating the

effects of climate change, but will still likely exceed $100

billion per year. The public sector does not have the resourc-

es to support all of these needs alone.

Governments, international institutions, and private

actors recognize the magnitude of this challenge. They

have begun to understand the limitations of existing ap-

proaches to international assistance and have made efforts

1 These estimates are based on the literature review found in “Financing

for sustainable development: Review of global investment requirement

estimates”, UNTT Working Group on Sustainable Development

Financing, 2013.

to improve aid effectiveness and engage the private sector

through agreements such as the 2005 Paris Declaration

on Aid Effectiveness, the 2008 Accra Agenda for Action,

and the 2011 Busan Partnership for Effective Development

Cooperation. Likewise, many private sector actors have

made public commitments to promoting sustainability

in their activities. For example, the 1260 signatories of

the United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible

Investment Initiative—including asset owners, investment

managers, and service providers—have $45 trillion dollars

in assets under management.

2

This commitment and oth-

ers reflect a growing recognition by the private sector of

the rewards of promoting economic and social prosperity

and environmental sustainability through their operations.

Innovative financing is critical to creating opportunities

for public-private sector collaboration that will help ad-

dress global challenges. Innovative financing has several

benefits compared to traditional financial approaches. For

example, it:

• Deploys significant, new private sector capital that

would otherwise not participate in social investments.

While not all of innovative financing capital is additional

2 See http://www.unpri.org/about-pri/about-pri/ for more information

(accessed September 2014).

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomesvi

Figure 1: A successful transition to sustainable development will require substantial resources

10 100 1,000 10,000

MDGs/SDGs

Infrastructure (non energy)

Land and Agriculture

Energy Efficiency

Renewable Energy

Universal Access to Energy

Climate Change Adaptation

Climate Change Mitigation

Biodiversity

Forests

Oceans

Estimates of annual investment needs for selected sustainable development sectors

USD billions

Notes: The x-axis is in logarithmic scale. There is significant overlap across sectors. MDGs/SDGs stand for the Millennium Development Goals and their post-2015

successors, the Sustainable Development Goals.

Source: UNTT Working Group on Sustainable Development Financing, “Financing for Sustainable Development: Review of global investment requirement esti-

mates”, 2013.

Box 1: Innovative Financing has evolved from mobilizing resources to private sector engagement

Policies and conferences

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Creation of the MDGs

Sri Lanka Development Bonds

EU ETS

Solidarity Levy on Airline Tickets

IFFIm

Product (RED)

Debt2Health

Green Bonds

AMC for Pneumococcal

Results-based financing

Financial Transaction Tax

Development Impact Bonds

Prominent Initiatives

Engaging

the

private

sector

(2006-

2015)

Aid-based

pilots

(2000-

2005)

International Conference on Financing for Development, Monterrey

Geneva & New York Declaration: Initiative to fight hunger and poverty; First global

intergovernmental dialogue on innovative means for financing development

Millennium Summit; Declaration on Innovative Sources of Financing for Development

Paris Conference on Innovative Development Financing Mechanisms:

Leading Group on Innovative Finance for Development created

International Conference for Financing for Development, Doha:

Doha Declaration on Innovative Financing for Development

I-8 Group created

General Assembly resolution devoted to innovative sources of financing for development

Busan Declaration to further develop innovative finance mechanisms to mobilize private

finance for share development goals; Rio Declaration to scale up innovative financing

UN General Assembly to develop post-2015 goals

Source: World Economic Social Survey 2012 “In Search of New Development Finance”, Department of Economic and Social Affairs UN; “Delivering the Post-2015

Development Agenda: Options for a New Global Partnership”, Center on International Cooperation 2013; Dalberg analysis.

INTRODUCTION: The Unrealized Potential Of Innovative Financing vii

to either government official direct assistance (ODA) or

private philanthropic contributions, successful mecha-

nisms often channel resources to projects that would

not otherwise receive them. For example, guarantees

that enable investments in public goods (such as infra-

structure) and impact investing funds support small and

medium enterprises that might otherwise struggle to

access capital.

• Transforms financial assets through financial structuring

and intermediation to meet the needs of development

programs by distributing risk, enhancing liquidity, reduc-

ing volatility, and avoiding timing mismatches. Innovative

financing mechanisms channel funds from people and

institutions that want to make investments, to projects

that require more resources than traditional donors and

philanthropies can provide. For example, green bonds

and other thematic bonds provide capital to support

investments in low-carbon infrastructure such as wind

farms, sustainable forestry management, and urban

infrastructure. In addition, innovative financing mecha-

nisms such as the Pledge Guarantee for Health provide

bridge financing for projects and institutions during the

gap period between when resources are committed and

resources are disbursed.

• Supports a cooperative public-private sector approach

to scale socially beneficial operations that require

significant capital outlays and traditionally sit squarely in

the realm of the public sector. In many sectors—such as

health, financial services, and agriculture—private com-

panies with the expertise to design, produce, market,

and distribute new products are crucial to creating social

change. Innovative financing mechanisms can adjust

incentives to encourage private companies to make

the investments necessary to create new products

and enter new markets. For example, the pneumococ-

cal advance market commitment sponsored by GAVI

reallocated demand risk for pneumococcal vaccines

in developing countries, which allowed pharmaceuti-

cal companies to produce more vaccines at scale and

dramatically lower the vaccines’ cost per dose.

Private sector actors have also benefited from innova-

tive financing mechanisms. In addition to creating chan-

nels for private actors to deploy capital to support develop-

ment, innovative financing mechanisms also offer private

sector actors risk-adjusted financial returns and access to

new markets. Bonds guaranteed by AAA rated international

organizations and issued in currencies with low volatility

offer a low-risk opportunity for both institutional and retail

investors to buy low-risk assets while channelling resources

to sectors that support positive development outcomes.

Most microfinance investment funds and impact invest-

ing funds also aim to offer risk-adjusted market returns.

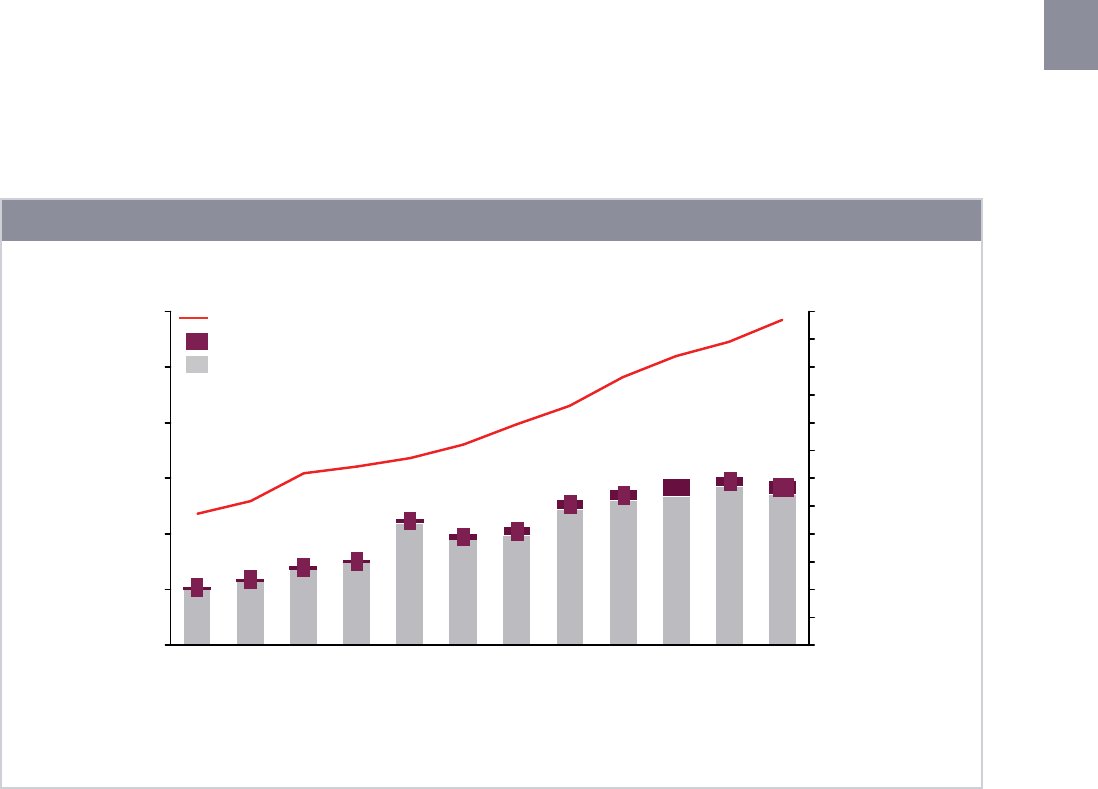

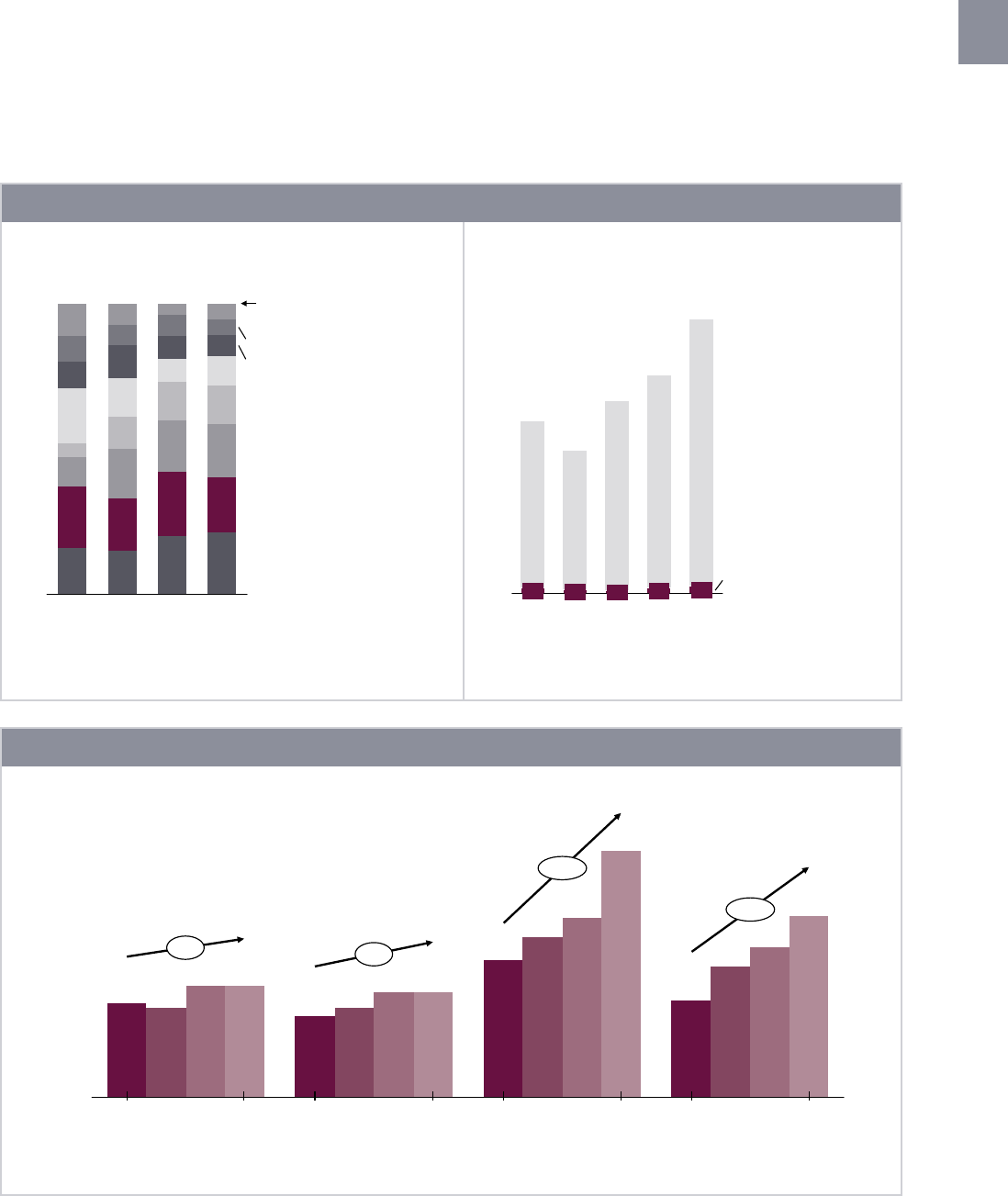

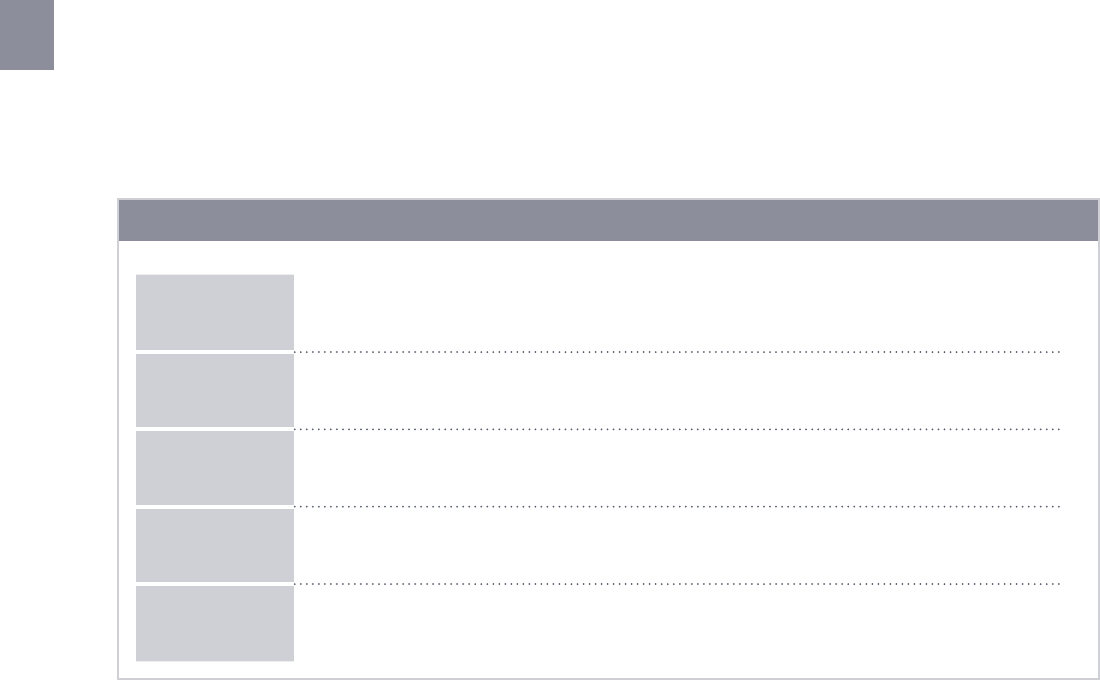

Figure 2: Innovative financing is a small component of public assistance

Evolution of funding for public goods in developing countries, 2001-2012

$ billions

1,000

150

300

0

250

200

100

50

0

4,000

4,500

6,000

3,000

3,500

2,000

2,500

1,500

500

5,000

5,500

72

200

4

200

5

3

13

61

5

200

9

2

96

9

77

110

137

200

8

2010

75

69

143

9

99

132

2011

59

148

200

6

200

3

Official aid flows and innovative financing resources mobilized

152

114

4

3

2012

Net Total Developing Country Government Expenditure

11

107

9

200

7

147

131

8

140

123

200

2

135

100

200

1

3

54

51

Innovative financing resources mobilized (left axis)

Official aid flows (left axis)

Net government expenditure (right axis)

Notes: Net Government expenditure does not include general budget support and loan disbursement to public sector; Official aid flows include Official

Development Assistance and Others Official Flows; Innovative finance data is based on 278 innovative finance initiatives where volume data broken down by year

was available. It assumes that innovative financing is additional to official aid.

Source: Development initiatives, “Investments to End Poverty,” 2013; OECD DAC Table 1; Innovative Financing Initiative Database; Dalberg analysis.

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomesviii

Guarantees can facilitate investments in new markets,

while results-based financing and performance-based con-

tracts create opportunities for private companies to profit-

ably provide goods and services in markets they otherwise

would not touch.

Despite its benefits, innovative financing remains a

small component of public sector development as-

sistance. While the public sector has expressed renewed

interest in engaging the private sector, few successful

partnerships have been formed. Innovative financing is a

small component of ODA, and an even smaller percentage

of government expenditures in developing countries and

foreign direct investment.

Innovative financing is hampered by an inefficient mar-

ket that constrains supply and diminishes demand. The

cost of developing and deploying new mechanisms, the

limited participation of investors beyond the traditional aid

community, and the lack of effective feedback loops have

thus far prevented innovative financing from reaching its

potential. If the sector can recognize and surmount these

barriers, it will be able to grow and create opportunities for

bankable investments to drive new solutions to develop-

ment challenges.

Within the development community, there is a clear

need—and a professed desire—to collaborate on in-

novative financing. This report asks: how can private

and public sector funders collaborate to channel more

resources to achieve development outcomes? Beyond

focusing on innovative financing as a source of capital that

complements traditional assistance, the report focuses on

how specific innovative financing mechanisms can support

development goals. The report is the cornerstone of a larger

initiative that mobilizes investors, companies, and policy-

makers to use innovative financing approaches to achieve

development goals.

A common language that appeals to actors in both

the private and public sector will facilitate the growth

of innovative financing. Through over 100 discussions

with representatives of government agencies, banks,

foundations, non-profits, and private companies, we have

heard concerns that innovative financing advocates fail to

understand the business models of private investors, fears

that private companies will earn extraordinary profits at the

expense of the world’s poor, and disappointment at the

lack of transparency and performance history within the

market. This report, which was co-sponsored by a corporate

foundation and a donor government, aims to address these

issues directly by highlighting how novel instruments and

initiatives can produce positive outcomes for both public

and private actors.

This report intends to demonstrate how innovative

financing can align with the strategic objectives of mul-

tinational corporations, financial institutions, interna-

tional development agencies, and private foundations—

and enable collaboration among these groups.

It is our hope that after reading this report:

• Multinational corporations and financial institutions

will understand opportunities for investment and col-

laboration that support their business models and align

with shareholder expectations.

• International development agencies will recognize the

potential for innovative financing mechanisms to sup-

port engagement with the private sector and address

specific global challenges.

• Private foundations will identify ways to engage with

public and private institutions to mobilize resources,

share information, and make strategic investments in

novel ideas.

CHAPTER 1: What is Innovative Financing? 1

Definition

Innovative financing means different things to different

people. In our interviews, we heard two distinct dimen-

sions of innovative financing. The first focuses on innovative

financing as a source of capital that complements existing

flows, particularly those from governments and philan-

thropies. Within this vision, innovative financing provides

resources that are stable, predictable, and supplemental to

official development assistance (ODA) from donor coun-

tries. The second dimension focuses on innovative financing

as a deployment (or use) of capital. This dimension focuses

on ways that innovative financing mechanisms can make

development initiatives more effective and efficient by

redistributing risk, increasing liquidity, and matching the

duration of investments with project needs. Our definition

of innovative financing mechanisms for development (“in-

novative financing”) encompasses both visions: approaches

to mobilize resources and to increase the effectiveness and

efficiency of financial flows that address global social and

environmental challenges.

The innovative financing landscape is showing a shift

from basic resource mobilization tools to a diverse

range of solutions-driven financing instruments. In

2001, bonds and guarantees focused primarily on resource

mobilization by leveraging the balance sheets of internation-

al finance institutions. Instead of providing funding at the

present time, public institutions either promised to repay

loans in the future or accepted the risk that projects may

not succeed, in order to encourage commercial investment.

In recent years, however, instruments through which the

private sector shares the risks and rewards from develop-

ment have gained more traction. This balance can occur

through an equity stake—which we often see in microfi-

nance and investment funds—or through results-based

financing mechanisms such as performance based con-

tracts or awards and prizes. Within international develop-

ment, which relies extensively on grant financing, this is an

important paradigm shift.

Our description of the market considers three dimen-

sions of existing innovative financing instruments:

type of instrument, characteristics of the innovation,

and financial function. We identified 14 different types

of instruments that are frequently classified as innovative

financing. For each type instrument, we found examples of

instruments that successfully mobilized resources for a de-

veloping country, demonstrated innovation, and used finan-

cial solutions to support positive development outcomes.

Figure 3 provides an overview of what these instruments

CHAPTER 1:

What is Innovative Financing?

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomes2

are, why we consider them innovative, and how they sup-

port international development.

Innovation is in the eye of the beholder. Innovative

financing is innovative when it deploys proven approaches

to new markets (including both new customers and new

segments), introduces novel approaches to established

problems (including new asset types), or attracts new

participants to the market (such as commercially-oriented

investors). For example, microfinance pioneers extended an

established service to a new market and, eventually, new

participants. Advance market commitments developed a

new approach to create incentives for commercial suppli-

ers to bring their products to market. Green bonds use an

established product—bonds issued by companies and in-

stitutions—to channel capital from institutional investors to

address a global challenge. Collectively, these mechanisms

represent innovative ways of achieving development goals.

Innovative financing creates value by producing posi-

tive development outcomes. In our survey of innovative

financing mechanisms, we identified three distinct chan-

nels by which innovative financing creates value: resource

mobilization, financial intermediation, and resource delivery.

While many schemes achieve two or three of these goals

simultaneously—and almost all mobilize resources—

this framework provides a high-level overview of the

main channels:

• Resource mobilization. Innovative financing brings ad-

ditional resources to bear for development challenges.

The mobilization of resources includes mandatory

mechanisms that capture the effects of negative exter-

nalities (e.g., Pigouvian taxes), voluntary mechanisms

(e.g., lotteries), and mechanisms that combine commer-

cial and philanthropic objectives (e.g., Product(Red)).

• Financial intermediation. Innovative financing creates

efficiencies by distributing risks across many parties, en-

hancing liquidity, and pooling resources. The intermedia-

tion function includes the development of institutional

capacity to reduce transaction costs (e.g., by pooling

small investment opportunities) and to reduce or share

financial and delivery risks (e.g., by promoting invest-

ment insurance).

• Resource delivery. Delivery refers to the allocation and

expenditure of resources either as part of an invest-

ment or as direct funding for development programs. It

includes initiatives that support a more effective deploy-

ment of resources by increasing the level of transpar-

ency (e.g., through commonly accepted metrics),

creating and aligning incentives (e.g., through pay-for-

performance contracts), and coordinating the activities

of different actors.

Figure 3: Innovative financing instruments introduce new products, expand into new markets, and attract new

participants

What is innovative? How does it support development?

New

Product

New Market New

Participants

Mobilize

Resources

Financial

Intermediations

Deliver

Resources

Securities and Derivatives

Bonds and Notes

X X X

Guarantees

X X X

Loans

X X

Microfinance Investment Funds

X X X

Other Investment Funds

X X X

Other Derivative Products

X X X X

Results-based Financing

Advanced market commitments

X X X

Awards and Prizes

X X

Development Impact Bonds

X X

Performance-based contracts

X X

Debt-swaps and buy-downs

X X

Voluntary contributions

Carbon Auctions (voluntary)

X X X X

Consumer Donations

X X

Compulsory charges

Taxes

X X

CHAPTER 1: What is Innovative Financing? 3

Market Overview

Using our broad definition, innovative financing

mechanisms have mobilized $94 billion since 2000. To

gain a better understanding of this market, we conducted

a survey of nearly 350 financing mechanisms that have

been recognized as innovative financing. In this survey, we

identified four distinct clusters that encompass 14 different

categories of instruments. Figure 4 provides an overview of

the categories that constitute innovative financing. In this

report, we use the term “amount mobilized” to compare

different mechanisms. “Amount mobilized”—which ac-

counts for the amount disbursed directly (for example, by

an investment fund) or indirectly (for example, by a com-

pany as a result of a guarantee)—differs from “total amount

committed,” which represents the amount originally

promised by investors, or the total amount invested. For

example, in the case of guarantees, “amount mobilized”

represents the total contingent liability of the mechanisms,

and in the case of investment funds, it represents the

total assets under management. More information about

our methodology, including a definition of each instrument

category, is in Annex 1.

3

3 While our definition of innovative financing is broad, we decided to

exclude some asset classes from our survey. We did not include bonds

to fund infrastructure or public private partnerships (PPPs) that focus on

infrastructure investment. In addition, we only considered mechanisms

where resources were deployed in developing countries. For example,

the Social Impact Bonds in the UK were intentionally excluded from our

study because they mobilized resources from within the UK that were

used within the UK.

Innovative financing is not financial innovation. The two

asset classes that mobilize the most resources, bonds and

guarantees, have existed for centuries. Bonds were first

issued by city-states in renaissance Italy in the 14th century

and insurance was first provided in 2500 BC to support the

transport of goods in Babylonia.

4

Even within the context of

international development, bonds and guarantees are not

new tools. The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency

(MIGA) was established in 1988, for example, and the Asian

Development Bank introduced partial risk guarantees in

1995. While the use of thematic bonds is relatively recent,

the World Bank has been issuing general purpose bonds

since 1947. Other instruments, such as microfinance funds

and impact investing funds, represent new and innovative

models for providing access to finance, but their underly-

ing business models are also well established within the

financial services industry.

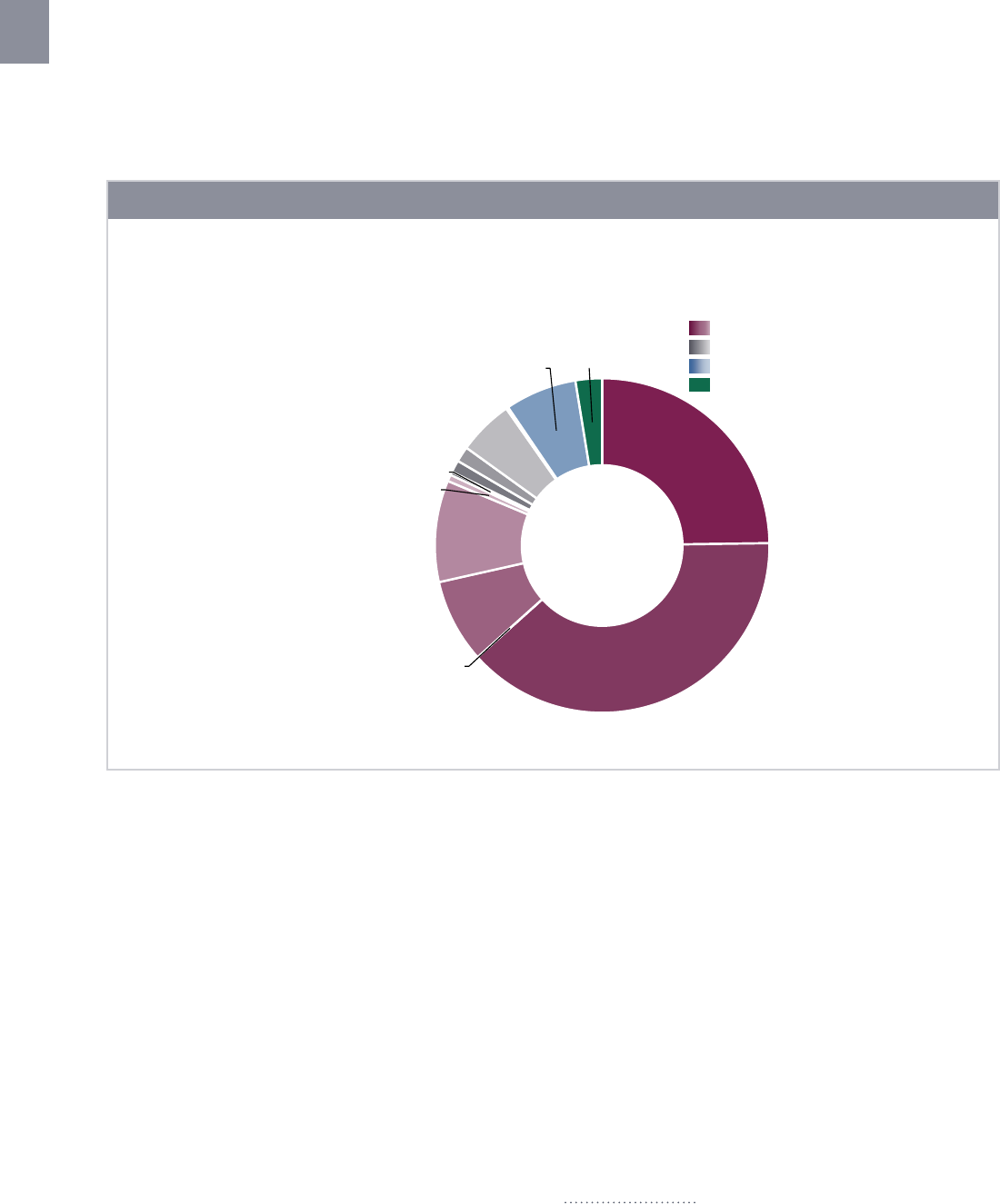

Securities and derivatives constitute more than 80%

of the amount mobilized between 2000 and 2013. The

largest category within securities and derivatives is guar-

antees ($36 billion, or 39% of the total), which reflects the

public sector’s ability to leverage capital by providing credit

enhancements. It also reflects the importance of MIGA,

which is the largest single mechanism in the database and

mobilized $24 billion between 2000 and 2013 (26% of the

total). Even when removing this large mechanism from the

database, securities and derivatives mobilized $53 billion

4 World Economic Forum, Rethinking Financial Innovation - Reducing

Negative Outcomes While Retaining The Benefits, 2012

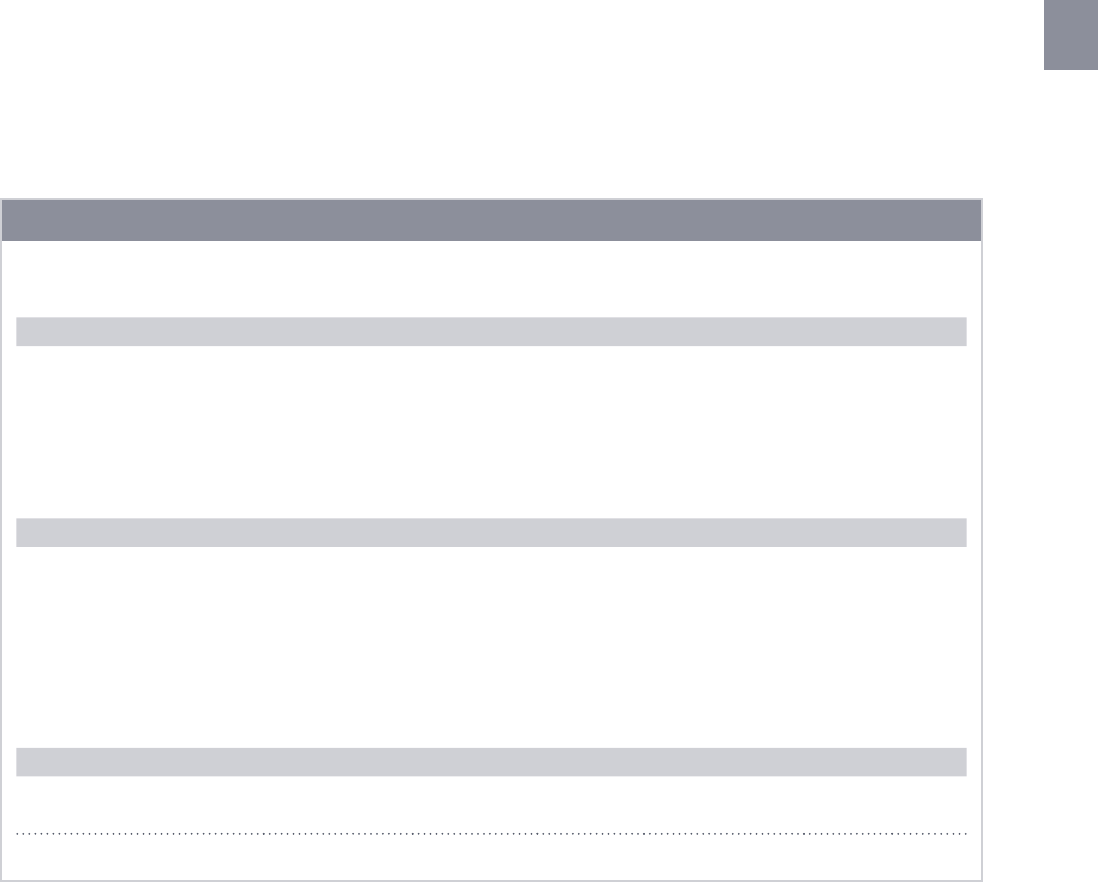

Box 2: Definitions of innovative financing from leading institutions

World Bank

“Innovative financing involves non-traditional applications of

solidarity, public private partnerships, and catalytic mechanisms

that (i) support fundraising by tapping new sources and engaging

investors beyond the financial dimension of transactions, as

partners and stakeholders in development; or (ii) deliver financial

solutions to development problems on the ground.”

—World Bank (2009), Innovating Development Finance:

From Financing Sources to Financial Solutions.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD)

“Innovative financing comprises mechanisms of raising funds or

stimulating actions in support of international development that

go beyond traditional spending approaches by either the official

or private sectors, such as: 1) new approaches for pooling private

and public revenue streams to scale up or develop activities for

the benefit of partner countries; 2) new revenue streams (e.g.,

a new tax, charge, fee, bond raising, sale proceed or voluntary

contribution scheme) earmarked to developmental activities on

a multi-year basis; and 3) new incentives (financial guarantees,

corporate social responsibility or other rewards or recognition)

to address market failures or scale up ongoing developmental

activities.”

—OECD (2009), Innovative Financing to Fund Development: Progress

and Prospects.

Leading Group on Innovative Financing for Development

“An innovative development financing mechanism is a mecha-

nism for raising funds for development. The mechanisms are

complementary to Official Development Assistance. They are

also predictable and stable. They are closely linked to the idea of

global public goods and aimed at correcting the negative effects

of globalization.”

—Leading Group on Innovative Financing

for Development (2012), FAQs: Innovative Financing

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomes4

from 2000 to 2013 (56% of the total). After guarantees,

thematic bonds—which dedicate resources to specific

development goals such as low-carbon infrastructure—have

mobilized the most resources ($23 billion or 25% of the to-

tal). Combined, these two asset classes make up over half

of the total amount mobilized through innovative financing.

Results-based financing is the second largest category

of mechanisms. Results-based financing refers to mecha-

nisms which use incentive-based payments to increase the

performance of investments and to transfer risk from the

investor that funds the delivery of goods and services to

the company or NGO that provides the goods and services.

The mechanism is an explicit contract between the out-

come funder and the delegated implementer who receives

a payment. Most results-based financing mechanisms,

such as performance based contracts ($5 billion mobilized

or 5% of the total) and advance market commitments ($1

billion mobilized or 1% of the total) are direct contracts be-

tween the public sector and a private sector implementer.

While small, results-based financing has grown rapidly from

$4 million in 2003 to $1.3 billion in 2012 (80% per year on

average). In addition, development impact bonds (DIBs) pro-

vide a new way to pool performance-based contracts and

facilitate private investment. While DIBs did not mobilize

resources between 2000 and 2013, new opportunities are

coming to market.

5

Voluntary and compulsory contributions contribute

only 10% of the total innovative financing mechanisms.

The largest mechanism within this category is the voluntary

carbon market in which companies purchase carbon credits

to offset emissions. Other voluntary mechanisms, such as

efforts to tie a percentage of companies’ profits to global

challenges, have limited scale and are difficult to replicate.

For example, since 2001, Product(Red) has contributed

$215 million to the Global Fund—this amount represents

less than 1% of total contributions to the fund.

6

Within the

category of compulsory contributions, the largest single

example is the “solidarity levy on airline tickets,” a small tax

5 For example, D. Capital launched a DIB to support malaria prevention

and control in Mozambique in 2013. In 2014, UBS Optimus Foundation

and the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation recently approved

funding for the first DIB in education, supporting the work of Educate

Girls, an NGO operating in government-run schools in Rajasthan, to

enroll and retain girls as well as improve learning outcomes for all

children.

6 Global Fund Pledges and Contributions to Date, http://

www.theglobalfund.org/documents/core/financial/

Core_PledgesContributions_List_en

Figure 4: Bonds and guarantees are the largest innovative financing mechanisms

Amount mobilized by innovative financing mechanisms, 2000-2013

Percent of total mobilized (n=278)

Bonds ; 24.8%

Guarantees

;

38.6%

Development Impact Bonds; 0.0%

Investment funds

; 8.1%

Microfinance

; 9.8%

Other derivative products

; 0.6%

Awards and Prizes

; 0.3%

Advanced Market Commitments

; 1.2%

Debt-swaps and buydowns

- - ; 1.5%

Performance-based contracts

; 5.3%

Consumer purchases

; 0.2%

Auctions

; 6.9%

Taxes and

Levies

; 2.6%

Source: Innovative Financing Initiative Database; Dalberg analysis

Securities and Derivatives

Results-based mechanisms

Voluntary Contributions

Compulsory Charges

Source: Innovative Financing Initiative Database; Dalberg analysis.

CHAPTER 1: What is Innovative Financing? 5

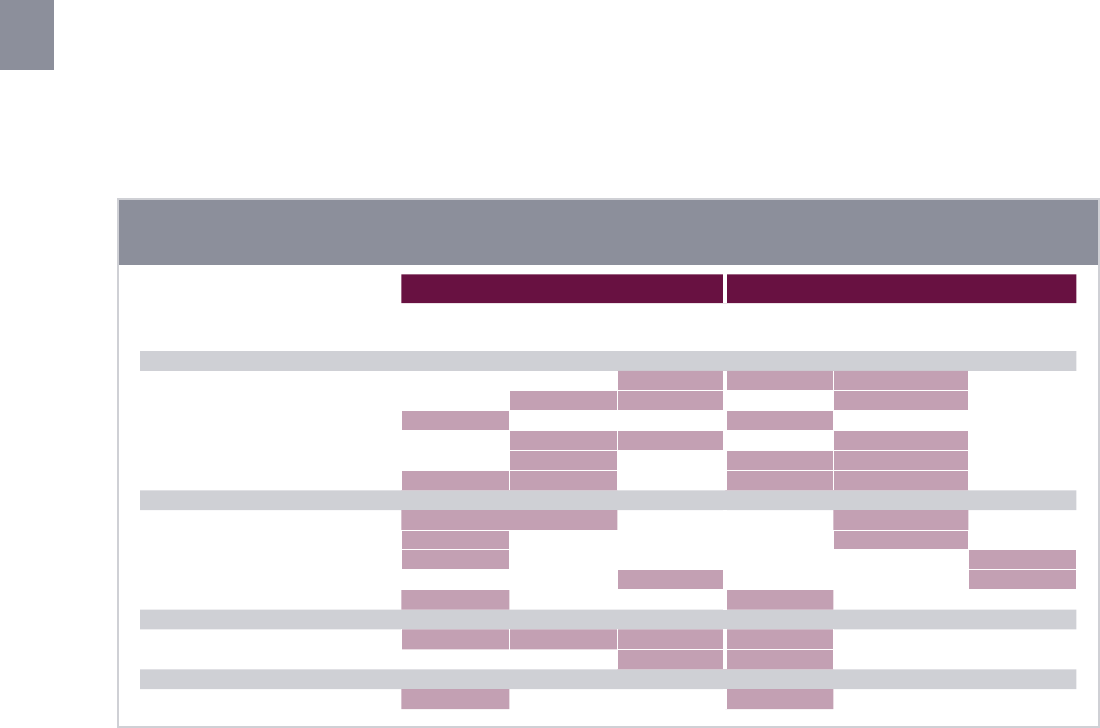

Figure 5: Innovative financing mechanisms have focused on a range of development challenges

Innovative financing mechanism by sector

1.2

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.0

Average size of mechanism (USD billion)

Number of mechanism

Access to

Finance

155

24

27

44

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

4

4

2

5

83

Energy and

Environment

Agriculture Health Disaster

Response

Education Housing Technology Multiple

Number (left axis)

Average instrument size (right axis)

E.g. microfinance, SMEs,

investment funds

E.g. guarantee facilities,

funds, currency swaps with

multi-sector mandates

Note: Sector information was available for 348 mechanisms. Average initiative size was based on data for 278 mechanisms. Other smaller sectors not shown

include Technology, Housing and Urban Development, Water and Sanitation, ICT and Media.

Source: Innovative Financing Initiative Database; Dalberg analysis.

on airline tickets in certain countries that mobilizes private

sector funds to support UNITAID.

7

It has raised $1.9 billion,

or 65% of UNITAID’s funds, since its inception in 2006.

An independent evaluation found that the levy has had no

negative effects on airline revenue or profitability, air traffic,

travel industry jobs, or tourism. While taxes and levies are

established tools for transferring resources from the private

sector to public purposes, novel mechanisms such as the

solidarity levy have successfully given international develop-

ment actors an additional and predictable revenue source.

Many innovative financing initiatives seek to effect

change in various sectors, which indicates a desire by

initiative sponsors to diversify exposure and highlights

the need for cross-cutting solutions to address financial

challenges shared by many sectors. Since 2000, innova-

tive financing mechanisms have mobilized over $30 billion

to support investments in energy and environment ($14

billion), access to finance ($9 billion), and global health ($7

billion), with an additional $43 billion across multiple sec-

tors. Innovative financing has had limited interaction with

the agriculture, education, and water sectors.

7 Nine countries have implemented the air ticket levy: Cameroon, Chile,

Congo, France, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritius, Niger and the Republic of

Korea.

Nearly all innovative financing mechanisms combine

public sector resources with private sector resources

and expertise. In terms of amount mobilized, both the pub-

lic and private sectors have been important sources of capi-

tal. The largest category of innovative financing ($44 billion)

is public sector investments in the private sector through

mechanisms such as guarantees, which mobilize invest-

ment, and results-based financing mechanisms, through

which the public sector hires private companies to provide

public goods. Public investments in the public sector ($4

billion) occur through mechanisms such as debt-swaps and

dedicated levies. The private sector provides capital ($30

billion) to the public sector through voluntary and compul-

sory contributions and investments, such as bonds. The last

category, private sector investments in the private sector

($15 billion), captures resources from microfinance funds

and impact investing funds.

Most securities aim to provide risk-adjusted market

returns.

8

While mechanisms that offer below-market

returns remain an important part of the innovative financing

landscape, mechanisms that target risk-adjusted returns

are increasingly prominent. Bonds, which make up 30%

of the amount mobilized by innovative financing securities,

8 It is too early to determine the actual financial returns of many

innovative financing mechanisms. For this survey, we used targeted

returns.

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomes6

Figure 6: Most innovative financing mechanisms support transfers between the public and private sectors

Private sector participation in innovative financing mechanisms, 2000-2013

Number of mechanisms (x-axis) and amount mobilized, USD million (y-axis) (n=278)

Invests capital (source)

280 260 240 220 180 160 120 140 60 80 20 40 200 100 0

15,000

Private Sector

(n=222)

Public Sector

(n=56)

Public Sector

45,500

Private Sector

30,500

44,300

48,100

3,800

Receives capital (use)

Source: Innovative Financing Initiative Database; Dalberg analysis.

Figure 7: The majority of instruments target risk-adjusted market returns

Target Financial Performance for Securities, Funds and Derivatives, 2000-2013

$ million (n=225)

Other investment

funds

(n=82)

0%

Loans

(n=4)

5,800

Other derivative

products

(n=8)

Guarantees

(n=17)

36,000 23,200

Microfinance

investment

funds (n=112)

Bonds

(n=14)

4%

1,800 9,100 600

Securities and Funds

Derivatives

Below Market Returns

Risk-Adjusted Market Returns

Source: Innovative Financing Initiative Database; Dalberg analysis.

CHAPTER 1: What is Innovative Financing? 7

are typically guaranteed by AAA rated international orga-

nizations. Returns vary with the issuing currency, and the

majority of bonds are issued in currencies with low volatil-

ity. Derivative products, including guarantees, tend to offer

below-market returns, but this is difficult to assess because

of the dominant role of the public sector.

Trends and Evolutions of Innovative

Financing Mechanisms

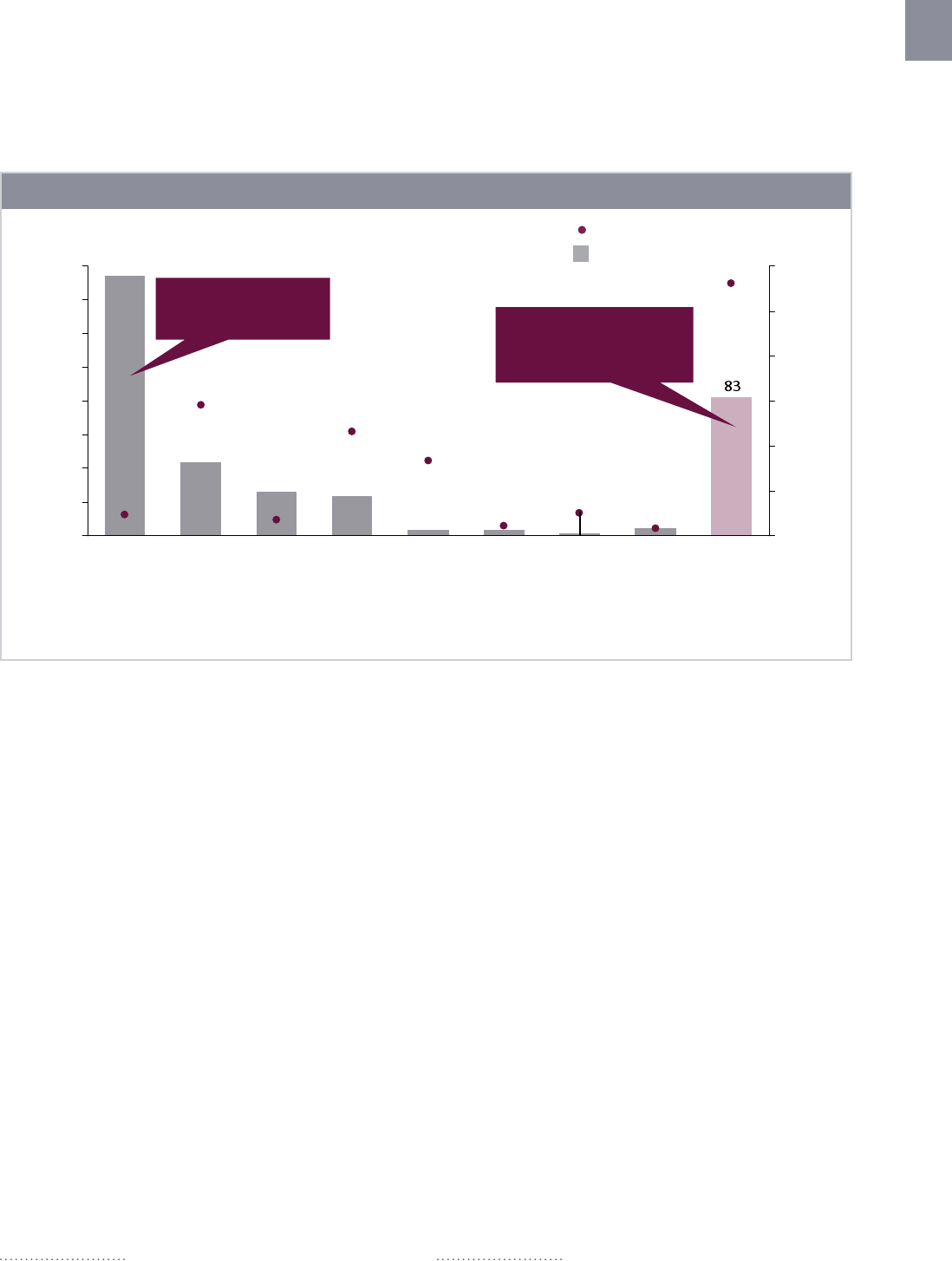

Since 2001, innovative financing for development has

experienced 11% annual growth. Starting at approxi-

mately $2 billion in 2001, the market has grown to nearly

$9 billion in 2012.

9

As shown in Figure 8, this reflects the

emergence of new instruments within the universe of

innovative financing, rather than the growth of existing

instruments. In particular, the emergence of microfinance

funds, thematic bonds, and auctions - such as the voluntary

carbon market - has driven most of the growth.

Market-based mechanisms that target risk-adjusted

returns have grown since 2001.

10

While mechanisms that

target below-market returns remain an important compo-

9 These calculations reflect a conservative estimate based on 137

mechanisms for which annual amounts were available.

10 Debt-swaps and buy-downs, donations as part of consumer purchases,

and taxes were excluded from this analysis.

nent of the landscape (53% of the total in 2012), there is an

increased focus on opportunities that target both social and

financial returns. There are two aspects of this trend. The

first aspect, from an investor perspective, is the emergence

of investments that offer risk-adjusted market returns. This

includes low-risk investments, such as green bonds that

are backed by development bank balance sheets, and more

risky propositions, such as microfinance funds and impact

investment funds. The second aspect, from an implementer

perspective, is the emergence of results-based financing

opportunities in which private companies and NGOs com-

pete to provide social goods.

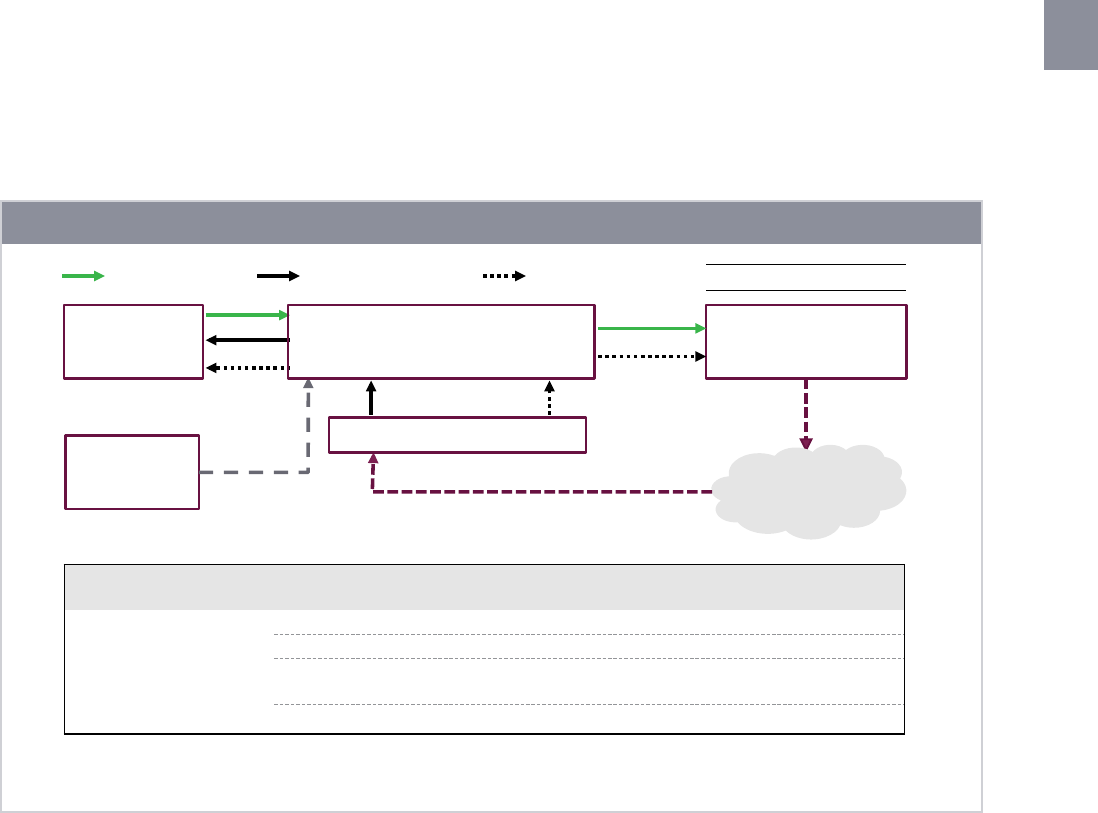

The innovative financing market is still evolving—some

models have proven to be successful, some are ripe for

scaling, and others are still new ideas in the testing

stage. Proven models, such as guarantees and bonds, have

easily replicated and scaled structures, benefiting from

clear standards for assessing risk and determining payment

terms; many have established track records. Models that

are ripe for scaling, such as performance-based contracts,

are also easy to create, but do not have enough perfor-

mance data to establish a mature asset class. Newer ideas,

such as AMCs and DIBs, are still being developed and

will require substantial support from concessional donors

before they can attract private capital and scale beyond the

pilot stage.

Figure 8: Innovative financing has grown through the introduction of new instruments

0

11,000

10,000

9,000

8,000

7,000

6,000

5,000

4,000

3,000

2,000

1,000

12,000

13,000

Annual amount mobilized, 2001–2012

$ millions (n=278)

2012

Auctions

Performance-

based contracts

Awards and prizes

2011 2010

AMC

2009

Bonds

Investment funds

2008

Microfinance Funds

Loans

Consumer Donations

2007

Other derivative products

Taxes

2006

Guarantees

Debt-swaps and

buy-downs

2005 2004 2003 2002 2001

Note: Annual mobilized data was not available for 141 instruments. For these instruments, we assumed that the entire amount mobilized was mobilized in the

launch year.

Source: Innovative Financing Initiative Database; Dalberg analysis.

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomes8

Figure 9: Innovative financing increasingly targets market returns

Resources mobilized for outcome-based solutions, 2000-2012

$ million (n=137)

2010 2011 2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2009

2008

Results based finance

Below Market Returns

Risk-Adjusted Market Returns

Note: Debt-swaps and buy-downs, Donations as part of consumer purchases, and Taxes were excluded from this analysis

Source: Innovative Financing Initiative Database; Dalberg analysis.

Figure 10: Established instruments rely on standards and mobilize more resources

Landscape of innovative financing mechanisms

Taxes

Carbon Auctions

Consumer Donations

Simpler structures

Longer track record

Bonds and Notes

AMCs

Performance-based Contracts

Microfinance Funds

Debt-swaps/buy-downs Awards and Prizes

Loans

Other Investment Funds

Other Derivative Products

---Development Impact Bonds

Guarantees

Newer Ideas

Scaling Opportunities

Proven models

Bubble size = Total

$B mobilized

Note: No known Development Impact Bonds have been successfully issued to date although many are under development.

Source: Innovative Financing Initiative Database; Dalberg analysis.

CHAPTER 1: What is Innovative Financing? 9

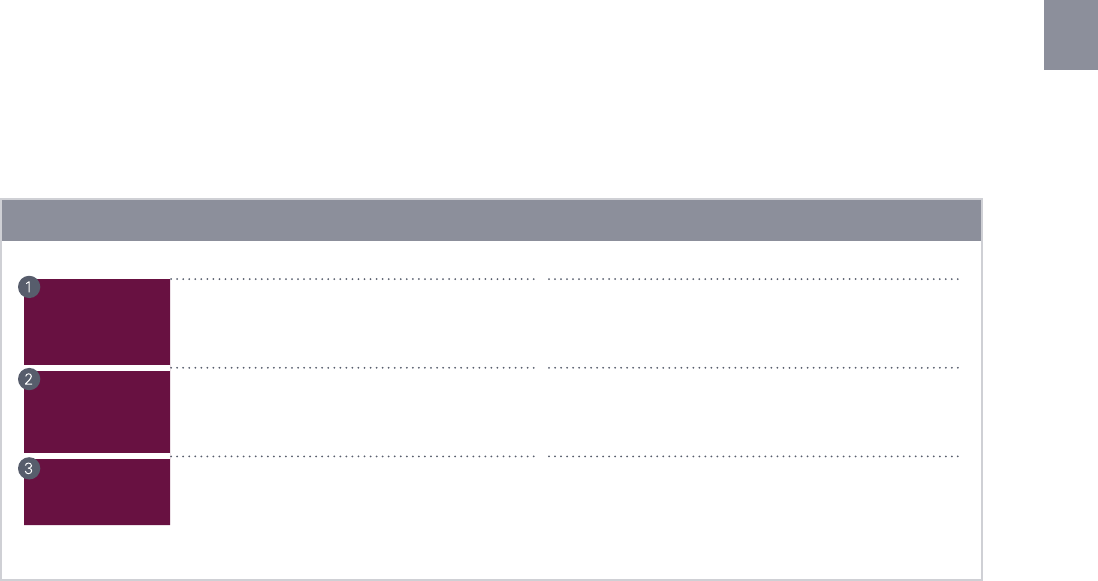

Box 3: Characteristics of dierent market segments

Newer Ideas Opportunities to Scale Proven Models

Funds mobilized

to date

Less than USD 100 million or

only one instrument

Between USD 100 million and

USD one billion from multiple

instruments

Greater than USD one billion

from multiple instruments

Track record Little or none One or more clear success

stories since 2006

In use before 2006

Complexity Technically difficult to structure Structure may be complex, but

there are existing templates

Simpler structures or many pre-

existing templates

R&D cost High R&D cost and lengthy

development runway

Moderate R&D cost and

development runway

Relatively low R&D cost and

quick to launch

Stakeholder

coordination

Multiple stakeholders required

for success, across public/

private/civil sectors

Multiple stakeholders required

for success

Coordination needed for a few

stakeholders or stakeholders

within only one group

Applicability Potentially limited to only certain

applications

Many applications but still

limited number demonstrated

so far

Has been applied to many

sectors and asset classes

Examples • AMC (AMC for Pneumococcal)

• DIBs (Malaria in Mozambique

Performance Note)

• Impact Investing Funds (The

Global Health Investment

Fund)

• Performnce-Based Contracts

(Mexico PES)

• Microfinance

• Bond (WB Green Bond)

• Guarantees (DCA Guarantees)

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomes10

CHAPTER 2:

How Does Innovative Financing Create Value?

Innovative financing mechanisms are tools to ad-

dress specific market failures and institutional barriers

that hinder global development. Innovative financing

mechanisms encompass a broad range of structures that

can allow investors, company managers, and government

officials to develop new strategies to address develop-

ment challenges. However, not all innovative financing

mechanisms are appropriate for every challenge. This

chapter highlights how different types of innovative financ-

ing solutions can produce positive outcomes and address

specific barriers.

Innovative financing instruments have been used to

produce a range of development outcomes. Innovative

financing has provided people in developing countries

access to goods, services, and capital. Microfinance

alone, for example, has provided loans to nearly a billion

people in 2012.

11

For private companies, innovative financing has been a

source of capital as well as a mechanism to create markets.

Guarantees enable investments, while performance-based

contracts create opportunities to deliver services. Financial

intermediaries have benefited primarily through access to

markets. For example, the market for green bonds is on

11 Source: MixMarket.com (accessed May 2014).

track to grow to $40 billion in 2014 through bonds issued

both by governments and corporations.

12

National governments and international donors have ben-

efited from innovative financing that funds public goods,

such as low-carbon infrastructure. Finally, innovative financ-

ing has also increased value for money within international

development, allowing donor agencies to achieve more

with the same—or fewer—resources. Figure 11 provides an

overview of how different innovative financing mechanisms

produce different outcomes for different actors. Bonds,

for example, provide capital for international donors, new

markets for financial intermediaries, and both capital and

public goods for national governments. The outcomes of

various innovative financing mechanisms are described in

more detail below.

Outcomes for Consumers and Private

Companies

Innovative financing has provided consumers with ac-

cess to essential goods and services and has provided

companies with access to markets. Successful innovative

financing mechanisms remove barriers to entry and enable

commercial investments in new products and markets.

12 Green Bonds Market Outlook 2014, Bloomberg New Energy Finance,

http://about.bnef.com/white-papers/green-bonds-market-outlook-2014/

(accessed June 2014)

CHAPTER 2: How Does Innovative Financing Create Value? 11

Typical barriers include: business models that are below

scale to be sustainably viable, market failures (such as lack

of information) that prevent the cost-effective delivery of

services, lack of facilities to manage and reallocate risk,

and inefficient markets that create high transaction costs.

Innovative financing mechanisms address these prob-

lems through resource mobilization, (e.g., driving invest-

ments as the microfinance industry became commercially

sustainable), financial intermediation, (e.g., reallocating

the business risk associated with producing health com-

modities), and improved resource delivery (e.g., sharing

information about new products such as product-linked

savings accounts.)

Case study 1: Access to essential health commodities

through Advance Market Commitments accelerates

the flow of capital to public goods that are not

economically viable without public support.

How it works: In an advance market commitment (AMC),

a buyer—typically a government or international organiza-

tion—agrees to a predetermined purchase price for a good

or service with a provider—typically a private company.

Originally, AMCs were conceived as a means to encourage

companies to invest in research and development for new

products, but it has also been used to increase production

for an existing product. Under the Pneumococcal AMC, for

example, donors pledged $1.5 billion to fund the subsidized

purchase of 2 billion doses of pneumococcal conjugate

vaccine (PCV) beginning in 2009.

13

In exchange for this

subsidy, manufacturers agreed to sell PCVs to low-income

countries at a price no greater than $3.50 for the next ten

years. As a point of comparison, the Pneumococcal AMC’s

prices for PCV are over 90% lower than those in high-

income markets.

13 As of December 2013, $652 million had been disbursed, which is the

number used to calculate amount mobilized in the database.

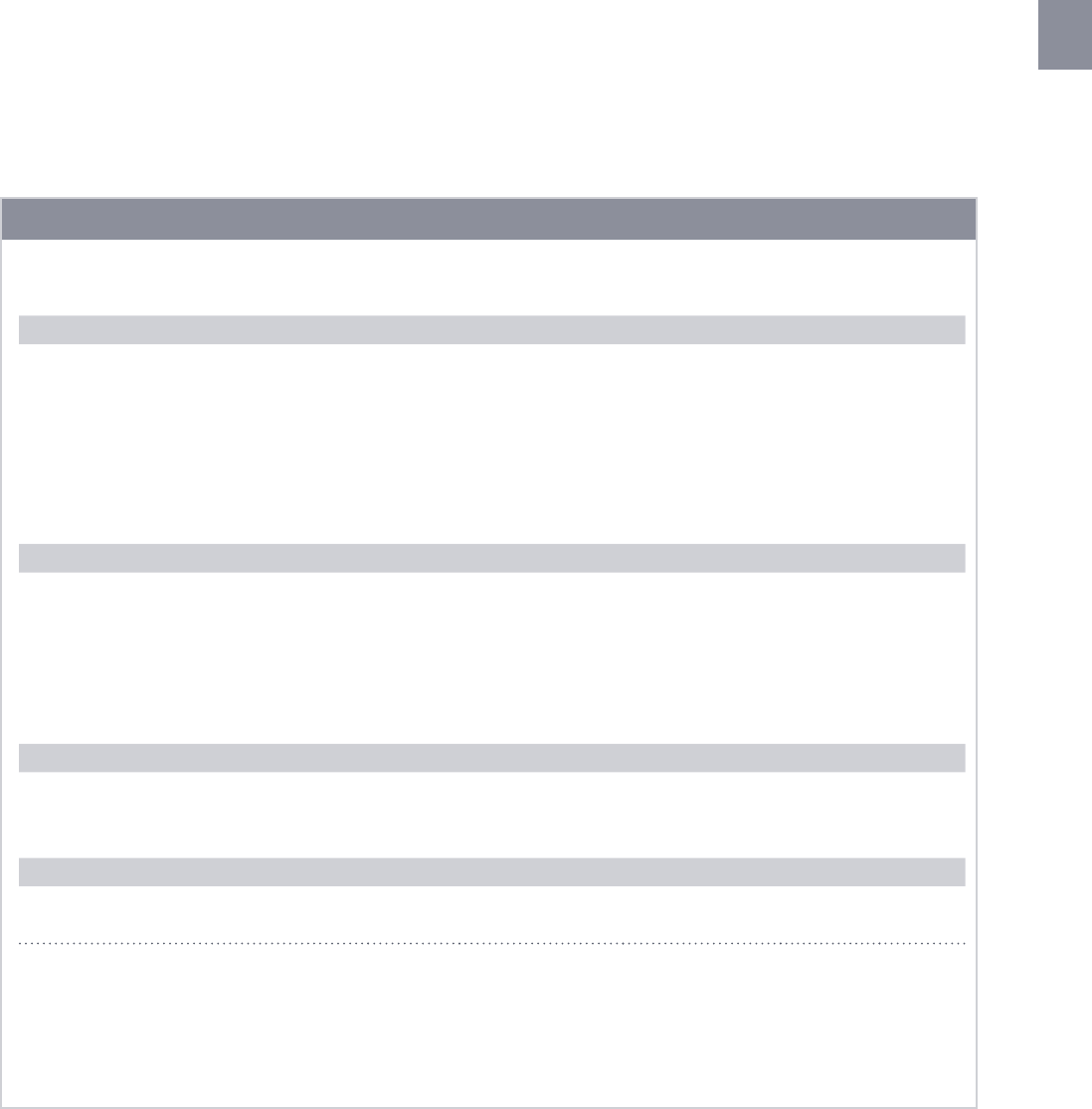

Figure 11: Innovative financing instruments produce a range of outcomes

Outcomes of selected innovative financing instruments for different stakeholders

Access to Markets Public Goods Access to Goods Access to Services Access to Capital Value for Money

Customers/

Beneficiaries

Performance-Based

Contracts

Bonds

Taxes and Levies

Guarantees

Microfinance

Advance Market

Commitments

Development

Impact Bonds

Impact Investing

Funds

Private

Companies

Financial

Intermediaries

National

Governments

International

Donors

Proven

Models

Opportunities

to Achieve

Scale

Experiments

and New

Ideas

Note: The outcomes for proven models have been demonstrated while outcomes for replication opportunities and new ideas are more theoretical.

Source: Dalberg analysis.

Pneumococcal AMC

Start Year:

2009

Amount

Mobilized:

$1.5 billion pledged

$652 billion disbursed to date

Investors:

y Italy ($635 million)

y UK ($485 million)

y Canada ( $200 million)

y The Russian Federation ($80 million)

y Norway ($50 million

y The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation ($50

million).

Why is it

innovative:

The AMC created incentives for vaccine

research and production for developing

countries as donors commit funds to

guarantee the price of the vaccines once they

have been developed.

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomes12

How it achieves outcomes: An effectively designed AMC

creates value for consumers by making essential goods

available and by lowering prices, and creates value for pro-

ducers by creating a market for the good. Ideally, the prede-

termined price for the good or service would be calibrated

so that the provider has incentives to produce the good but

does not earn excessive profits—but this calibration is dif-

ficult to achieve in practice. For example, the designers of

the Pneumococcal AMC did not (and could not) know the

necessary capital expenditure and unit costs of scaling up

production of the vaccine when they set the upfront sub-

sidy and purchase price. As a result, they established prices

that they believed would attract suppliers to the market

while maximizing value for money.

14

The Pneumococcal AMC was the first attempt to use

an AMC to accelerate the introduction of a vaccine in

developing countries. Since its launch, two suppliers -

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Pfizer - have produced and

distributed 82 million doses of PCV to 24 low-income coun-

tries. While precise return data is not available, an indepen-

dent evaluation found that manufacturers likely earn returns

that are at or above 10-20% per year, which is consistent

with historic industry performance.

15

The AMC combined long-term commitments and tem-

porary subsidies to lower prices and create a market for

health commodities. Since its launch, participating suppliers

have expanded capacity and additional manufacturers have

expressed interest in joining the initiative. It is impossible to

know if the opportunity to provide the vaccine to millions of

people in new markets would have been enough to entice

low-cost manufacturers to participate without the advance

guarantee that vaccines would be purchased.

How it can be replicated: Beyond the pneumococcal

example, few AMCs have been considered as success-

ful in furthering development goals.

16

An AMC is a useful

innovative financing tool when private suppliers of goods or

services are involved, when providing the good or service

requires a high fixed-cost investment, and when demand

risk makes private companies reluctant to make the upfront

investment. However, when only these three criteria exist,

the AMC funder would typically find it more efficient to

14 See the pneumococcal AMC process and design evaluation (http://

www.gavialliance.org/results/evaluations/pneumococcal-amc-process-

design-evaluation/) for a more detailed discussion of the challenges of

designing the pneumococcal AMC.

15 (Chau, 2013)

16 In addition to the Pneumococcal AMC, there has been discussions of

using an AMC for rural energy in Rwanda and bioenergy in Sri Lanka.

offer a more traditional forward contract or a volume

guarantee with a single supplier. For example, power-

purchase agreements, in which a power purchaser (often

a state-owned utility) agrees to purchase energy from a

power utility for the next 10-20 years, are common tools

for financing electricity generating investments, including

renewable energy. Unlike advance market commitments,

power-purchase agreements do not aim to create a market

with multiple participants.

The more complex advance market commitment structure

is useful when the funders want to create a market in addi-

tion to providing a good and service. Specifically, AMCs are

well-suited for challenges with the following characteristics:

first, when private suppliers are not willing to be or cannot

be transparent about their costs. As a result, it is difficult

to determine the fair price that will attract new suppliers to

the market. Second, when payers can calculate a financial

benefit that allows them to set a price based on benefits

and not costs. This allows the donor that issues the AMC

to determine the ceiling of how much it is willing to pay to

induce market entry. Finally, AMCs are appropriate when

there is a benefit in having multiple companies compete for

the market rather than a funder partnering with one or two

organizations upfront. For some development challenges,

such as providing health commodities, donors will want to

work with multiple suppliers to avoid being dependent on

a single supplier. In other circumstances, such as provid-

ing electricity, the nature of the product requires a limited

number of suppliers.

Outcomes for National Governments

Innovative financing has attracted private resources

to fund development projects and public goods.

Successful innovative financing mechanisms create incen-

tives for private companies to invest in projects that benefit

people in developing countries, in particular people at the

base of the pyramid. These incentives include: enhancing

profit margins by blending capital from socially motivated

investors with more profit-oriented organizations, enhanc-

ing credit by shifting project risk to organizations with more

creditworthy balance sheets, and creating marketing op-

portunities by being associated with socially responsible in-

vestments. We provide examples of different mechanisms

that provide these incentives for private companies below.

Case study 2: Capital for investments in low-carbon

infrastructure through green bonds.

How it works: The World Bank first issued green bonds in

2008 to finance investments in low-carbon infrastructure,

CHAPTER 2: How Does Innovative Financing Create Value? 13

such as renewable energy infrastructure and energy ef-

ficiency improvements. In the past five years, green bonds

have grown considerably. According to Standard & Poor,

government and corporations issued $10.4 billion in green

bonds in 2013. A recent report by Bloomberg New Energy

Finance points out that the market is growing fast; at its

current pace, total volume of green bonds will surpass $40

billion by the end of 2014.

Green bonds have grown quickly because they can be eval-

uated using standard risk models, provide a risk-adjusted

return that meets investor expectations, and offer investors

the opportunity to be associated with a positive environ-

mental outcome.

17

To date, institutions with excellent credit

ratings and strong balance sheets have issued green bonds.

Notably, the yield for green bonds is the same as traditional

bonds offered by the same institution that are not dedicated

to low-carbon infrastructure.

How it achieves outcomes: Green bonds have suc-

cessfully channeled capital to low-carbon infrastructure,

which supports climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Furthermore, the use of green bonds by multinational cor-

porations suggests that this mechanism will scale beyond

the public sector and become a mainstream investment

product.

While the mainstreaming of green bonds is an impres-

sive achievement, given the lack of standards about what

constitutes a green investment, it is unclear how multina-

tional corporations will use the proceeds of these bonds.

This uncertainty presents a significant investment risk and,

if left unaddressed, might limit green bonds’ effective-

ness to raise funds that support development goals in the

future. Based on an independent review with the Center for

17 For example, a two-year green bond issued by the World Bank in August

2013 had an issue yield equivalent to a spread of +8.3 basis points over

a comparable U.S. Treasury.

World Bank

Green Bonds

Start Year:

2008

Amount

Mobilized:

$4.4 billion

Investors:

y Institutional investors (e.g., Blackrock, Calvert

Investments, Nikko Asset Management)

Pension Funds

y DFIs

y Government backed funds

Why is it

innovative:

Green bonds provide an instrument through

which investors who are concerned with

the effects of climate change can make a

difference by specifically supporting climate

change related projects.

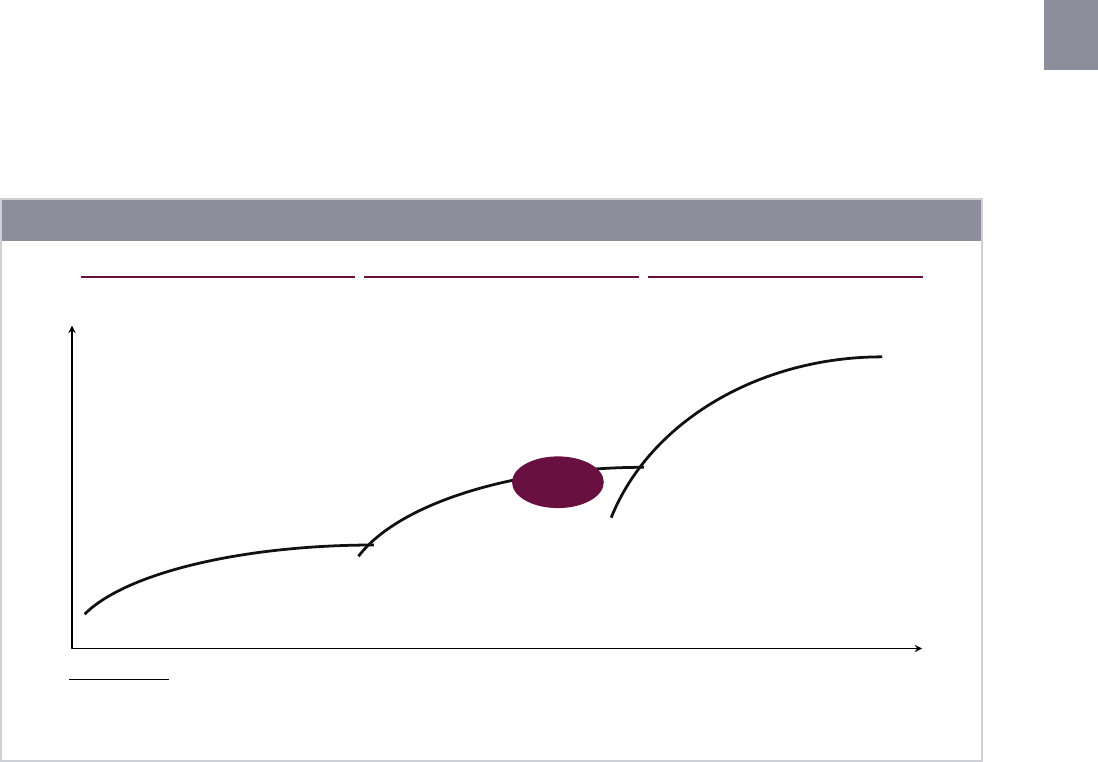

Figure 12: The market for green bonds is growing

Growth in green bonds issued by select international finance institutions, 2008–2013

$ million

2010 2009

414

414

2008 2013 2011

2,735

889

726

267

595

2012

730

793

480

2,119

714

451

1,381

0

0

0

0

12

24

EBRD

World Bank

EIB

Source: Innovative Finance Initiative Database; Dalberg analysis.

Innovative Financing for Development: Scalable Business Models that Produce Economic, Social, and Environmental Outcomes14

International Climate and Environmental Research at the

University of Oslo (CICERO), the World Bank identified cri-

teria for projects that can be financed through green bonds

to mitigate the effects of climate change and help countries

adapt to the effects of climate change. In addition, 24 banks

have signed green bond principles that provide voluntary

guidelines on the use of proceeds, process for project

evaluation, management of proceeds, and reporting.

18

As

shown in Table 1, the criteria for green bonds is very broad.

In addition, while individual institutions monitor the use of

green bond proceeds and evaluate the effects, there are no

standard mechanisms to verify that the bonds are actually

used to finance green projects or to compare the environ-

mental benefits of different bonds.

How it can be replicated: Green bonds demonstrate the

potential of using the balance sheets of international fi-

nance institutions to channel capital to global priorities. The

concept does not need to be limited to environmental proj-

ects. It can be used when there is a need for investment

in global priorities that surpasses the current resources of

18 As of May 2014, the following institutions are members of the Green

Bond Principles: Banca IMI S.p.A., Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria

(BBVA), Banco Santander S.A., Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Barclays

Plc, BlackRock, Inc., BNP Paribas, California State Teachers’ Retirement

System (CalSTRS), Citi, Crédit Agricole CIB, Danske Bank A/S, DNB,

HSBC Bank Plc, International Financial Corporation (IFC), JP Morgan

Chase & Co, KBC Bank NV, Mitsubishi UFJ Securities International Plc,

Natixis, Natixis Asset Management—Mirova, Nomura International

Plc, Nordea Bank Finland Oyj, RBC Europe Ltd, Société Générale CIB,

Standish Mellon Asset Management Company LLC, The Royal Bank of

Scotland plc (RBS), TIAA-CREF, Westpac Institutional Bank, World Bank.