Blended Finance Solutions for

Clean Energy in Humanitarian

and Displacement Settings

Lessons Learnt – An Initial Overview

January 2022

Acronyms

BMZ German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development

DESCO Distributed energy service companies

DIB Development Impact Bond

EDM Energy Delivery Models

ESDS Energy Solutions for Displacement Settings

EU European Union

GCR Global Compact for Refugees

GPA Global Platform for Action on Sustainable Energy in Displacement Settings

HIB Humanitarian Impact Bond

IB Impact Bond

ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross

IDP Internally Displaced Persons

IOM International Organisation for Migration

KKCF Kakuma Kalobeyei Challenge Fund

LPG Liquied Petroleum Gas

MRV Measuring, reporting and verication

NORAD The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation

NRC Norwegian Refugee Council

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PA Practical Action

PAYG Pay-As-You-Go

RBF Results Based Financing

RE4R Renewable Energy for Refugees

SDG Sustainable Development Goal

SEED Soutien Energétique et Environnemental dans la région de Diffa

SER Staff Eciency Ratio

SHS Solar Home System

SIB Social Impact Bond

Sida Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency

SNV (Netherlands) Foundation of Netherlands Volunteers

UN United Nations

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

WEF World Economic Forum

WFP World Food Programme

1. Introduction

05

2. Funding challenges for energy

programming in displacement settings

06

3. Blended nance

08

3.1.

3.2.

3.3.

3.4.

3.5.

3.6.

3.7.

What is blended nance?

What is the role of blended nance?

Why is blended nance relevant to humanitarian energy programming?

What does blended nance look like?

When and how to use blended nance solutions

Blended nance, subsidies and policy reform

Supporting mechanisms

4. Blended nance solutions for energy

programming in displacement settings

11

4.1.

4.2.

4.3.

4.4.

4.5.

Direct funding for the removal of commercial barriers

Technical assistance

Risk transfer mechanisms

Market incentives

Using more than one blended nancing mechanism

5. Conclusions, recommendations and next

steps

32

5.1.

5.2.

Conclusions

Recommendations

Works cited and consulted

36

Authors and acknowledgements

39

Contents

Cover Photo: The local volunteer Michael Gatluak clean the new solar panels at the

NRC oce in Mankien – South Sudan. Photo: NORCAP / Iban Colón

05

1. Introduction

04

Currently, over 235 million people require humanitarian assistance (UN OCHA,

2021). Of these, 91.9 million people have been recorded as displaced as a result of

persecution, conict, violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing

public order (UNHCR, 2021).

Energy is recognised as an enabler of basic human rights, however, a majority of

displaced populations still lack sucient access to clean, sustainable, reliable,

appropriate and affordable energy (GPA, 2021). According to estimates, 80 per cent

of refugees and displaced people in camps have minimal access to energy, with high

dependence on traditional biomass for cooking and no access to electricity (Lahn and

Grafham, 2015).

Limited access to energy can have severe repercussions on the health, safety and

security of displaced populations and limits their opportunities to learn, become

self-reliant and socialise with peers. Additionally, where the energy needs of the

displaced community are being met, the nancial and environmental costs tend to

be high because of poor practices, inecient appliances, high fuel costs and limited

monitoring of energy consumption. Furthermore, diesel-powered generators are one

of the most prevalent energy solutions for humanitarian operations due to the off-

grid location of the response or their connection to grids that suffer from brownouts

(drop in voltage) or blackouts. Although humanitarian organisations recognise their

moral and nancial obligation to ‘green’ their operations to minimise their climate and

environmental footprint, it is an economic challenge to do so even when the transition

to renewable sources of energy offers an opportunity to save money over the medium

to long term.

Unfortunately, traditional grant-based funding, which humanitarian organisations rely

on, is not sucient to deliver the energy needs of the displaced (household cooking,

household access to electricity, energy at service centres, such as health clinics and

schools, and for livelihood opportunities) or to support the required institutional energy

transition (see Chapter 2). In addition, due to its limitations, grant funding rarely results

in self-sustaining energy solutions. Also, grant funding is not readily accessible to

humanitarian actors to support their transition to more sustainable energy solutions.

As such, if humanitarian actors were to rely on grant funding, it is unlikely that SDG7

(ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy) will be achieved

in displacement settings. Blended nance may, however, be part of the solution to

bridging the funding gap and drive self-sustaining solutions in displacement settings

by accessing nancing from the private sector.

This report aims to provide an overview of blended nance mechanisms, their role

in delivering sustainable energy solutions as part of the humanitarian response,

highlighting key lessons learnt from their use in displacement settings and making

recommendations for their continued development.

1. Introduction

Woman cooking in the communal kitchen

of the Biogas plant at the POC (Protection

of Civilians Site) of Malakal – South Sudan.

Photo: NORCAP / Iban Colón

Blended Finance Solutions for Clean Energy in Humanitarian and Displacement Settings

0706

2. Funding challenges for energy programming in displacement settings

DELIVERING SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS AMIDST

SHORT-TERM BUDGET CYCLES

Traditionally, humanitarian actors have delivered energy

access solutions in displacement settings through free

distributions of goods and services funded by grants

from a variety of donors. Such approaches, however, do

not result in sustainable solutions, as the provision of

the goods and services usually cease once the grant

funds have been spent. In addition, the scalability of

most energy access projects is limited by the donors’

contributions and ongoing interest in the energy topic,

geographic location, humanitarian emergency or

protracted situation. This is further compounded by the

problem posed by annual budget cycles, which make

it almost impossible for the humanitarian sector to

implement energy projects, which can take up to ve

years, from the initial planning stage, to complete.

Furthermore, grant funding for decarbonising the

humanitarian response (e.g. transitioning from diesel-

based energy systems to solar solutions) or providing

electricity access to a displacement setting provides

additional challenges to traditional donors. For instance,

many donors offer core funding to humanitarian actors

and expect the grant to be used in the most resource-

ecient manner. Therefore, if solar solutions are more

cost-ecient than existing diesel-based systems, the

donor expects the humanitarian actor to transition to

the cheaper solution with the core funding it already

receives.

ADDITIONALITY OF ENERGY PROGRAMMING

Energy access programmes can, however, create

positive long-term effects that outweigh the original

project funds spent. For instance, it has been

calculated that every dollar spent on increased energy

access results in a return on investment to the value

of 1.40 USD to 1.70 USD from employment, improved

health, productivity, and time-saving.(Shell, Dalberg

& Vivid Economics, 2020). In addition, added benets

of displaced populations accessing clean energy can

also lead to higher education rates, reduced protection

risks, reduced environmental impact and access

to information through smart technology, including

phones and the internet, helping individuals make more

informed choices.

WHOSE ROLE IS IT; HUMANITARIAN OR

DEVELOPMENT ACTORS?

When traditional donors provide grants to humanitarian

organisations, they typically seek results with a direct

humanitarian impact and, as such, often view energy

projects, especially those that increase access to

electricity, as ‘development’ initiatives as the projects

tend to stretch over an extended time period and

results in long-term energy access solutions. The

energy or development colleagues of traditional

humanitarian donors, however, feel that providing

energy infrastructure in displacement settings should

be funded by their humanitarian counterparts, given the

context and the ‘temporary’ nature of the displacement.

Hence, we end up in a situation where donors see the

value in supporting energy projects but feel unable to

provide the necessary funding.

FINANCIAL CONTROLS AND LIMITATIONS ON

PROCUREMENT MODALITIES

Many humanitarian partners, especially those within

the UN system, have very restrictive nancial rules and

regulations which limit their ability to experiment with

new nancing strategies. For example, they are unable

to take loans or benet from any nancial mechanisms

that could be construed as a loan. Furthermore,

humanitarian partners have limited experience with

new procurement modalities such as “energy-as-a-

service” or energy asset leasing models, which limit

this potential avenue of private sector engagement and

nancing the delivery of sustainable solutions.

HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE IS UNDERFUNDED

Although we are at an all-time peak in terms of the

number of people in need of humanitarian assistance,

global funding for the humanitarian response has

plateaued, resulting in an unparalleled funding gap of

52 per cent (Chatham House, 2021). More specically,

current spending on cooking and power in displacement

2. Funding challenges for energy

programming in displacement

settings

settings has been estimated to be around 1.6 billion

USD. By 2030 future spending could be as high as 5.3

billion USD (Shell, Dalberg & Vivid Economics, 2020).

How will humanitarian organisations address this

future nancial need when they are already struggling

to meet today’s nancial demands?

CHALLENGING COMMERCIAL ENVIRONMENT

The acknowledgement of such shortfalls with

traditional grant-based solutions has resulted in the

promotion of market-based approaches where the

provision of energy services in displacement settings

are delivered by the private sector, with assistance from

humanitarian and/or government actors. In addition,

the private sector is showing an increased interest in

commercial opportunities to deliver energy access

for cooking (cookstoves and/or fuel) and electricity

(solar home systems and mini-grids) to the ‘bottom of

the pyramid’ and ‘last mile’ end-users. Many displaced

communities fall under such classication.

Commercial environments within refugee or migrant

camps are, however, subject to a unique set of rules and

regulations, which can be dicult for non-humanitarian

actors to navigate. In addition, there is a clash of

cultures. While humanitarian actors are focused on

providing protection to the displaced, the majority of

private sector actors a seeking commercially viable

business models, even if they have a strong stance

towards social responsibility. Overcoming this clash

can be problematic because the two entities speak

different ‘languages’ and have very different operational

risk proles. Furthermore, the lack of integration

of displaced populations into national strategies

perpetuates dependence on humanitarian aid. As such,

policies and the supporting ecosystem (e.g., recognition

of registration documents, right to work, cash-based

interventions, access to bank accounts, mobile money,

etc.) can be unfavourable for private sector investment

and associated delivery models.

Given the perceived ‘temporary’ nature of such settings

and the assumed lack of commercial opportunity

within displaced communities, the private sector is

cautious in its approach to delivering energy services

to the displaced. Refugee settlements, however, have

an average lifespan of 18 years (Haselip; 2022), and in

protracted situations, there is a demand for commercial

energy solutions. For instance, 53% of surveyed

refugees in Tanzania purchased their cooking fuel,

spending on average 12 USD a month per family, which

is approximately three times the national average. Of

those surveyed, 95% expressed a willingness to pay for

Liquied Petroleum Gas (LPG) as a cooking fuel (Rivoal

and Haselip, 2018).

Although such commercial opportunities exist, the

range of risks and uncertainties for commercial

entities and investors remain, especially with regards to

affordability of potential solutions. As such, traditional

approaches to nancing energy programmes cannot

be supported by the risk-return characteristics of

displacement settings. Therefore, alternative nancial

mechanisms are required and hence the interest in

innovative nance solutions for energy programmes in

the humanitarian sector.

Innovative nancing to replace grant funding

There is no agreed denition of ‘innovative nancing.’

It is understood that relevant stakeholders consider

innovative nancing to encompass one or more of the

following:

● Is everything that is not direct, traditional grant

funding;

● The generation of additional money from non-

traditional sources;

● Combining funds from multiple sources to

accomplish one nancing objective;

● Increasing the effective use of existing nancial

resources, including money received from

traditional humanitarian donors, i.e., achieving

more impact with the same amount of money;

● A nance mechanism that is new in the

humanitarian system or one in which there is little

experience; and/or

● Creating platforms which connect providers of

capital/funds with borrowers.

It is important to note that many innovative nance

solutions are designed in a way in which end users

(displaced people) - at least partially - pay for goods

or services. As such, it comes as no surprise that

innovative nance solutions remain underdeveloped in

the humanitarian system.

One type of innovative nancing is blended nancing. A

denition for blended nancing, an overview of blended

nance mechanisms, their role in delivering sustainable

energy solutions as part of the humanitarian response

is outlined in the remainder of this report, which

concludes with recommendations for their further

development.

Blended Finance Solutions for Clean Energy in Humanitarian and Displacement Settings

0908

3. Blended nance

3.1. What is blended nance?

Blended nance is dened as an approach for

increasing the amount of project funding by combining

different types of nancing from different sources

and/or for different purposes, which contribute to

development, social, environmental or humanitarian

goals and generate nancial returns. It is common

for one source of funding within the blended nance

solution to act as a catalyst for raising additional

funds.

In essence, blended nance is a mechanism that

allows organisations with different objectives to

‘invest’ alongside each other while achieving their own

objectives (International Bank for Reconstruction and

Development & World Bank, 2020).

There are three key characteristics associated with

blended nance, which are:

● Leverage: Use of humanitarian or development

nance and philanthropic funds to attract

commercial nance into projects.

● Impact: Investments that drive development,

social, environmental or humanitarian progress.

● Returns: Financial returns for private investors in

line with market expectations, based on real and

perceived risks (WEF & OECD, 2015).

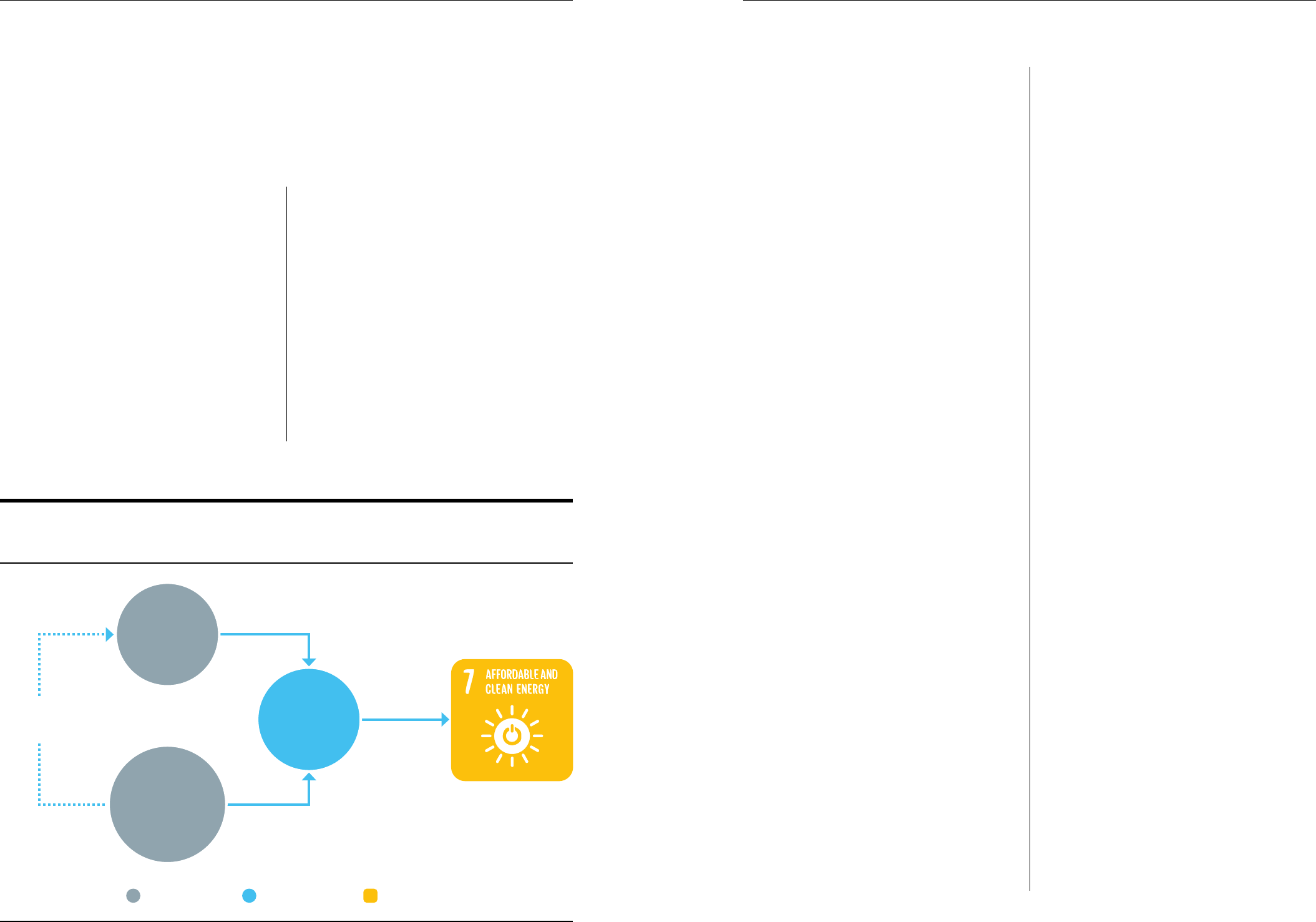

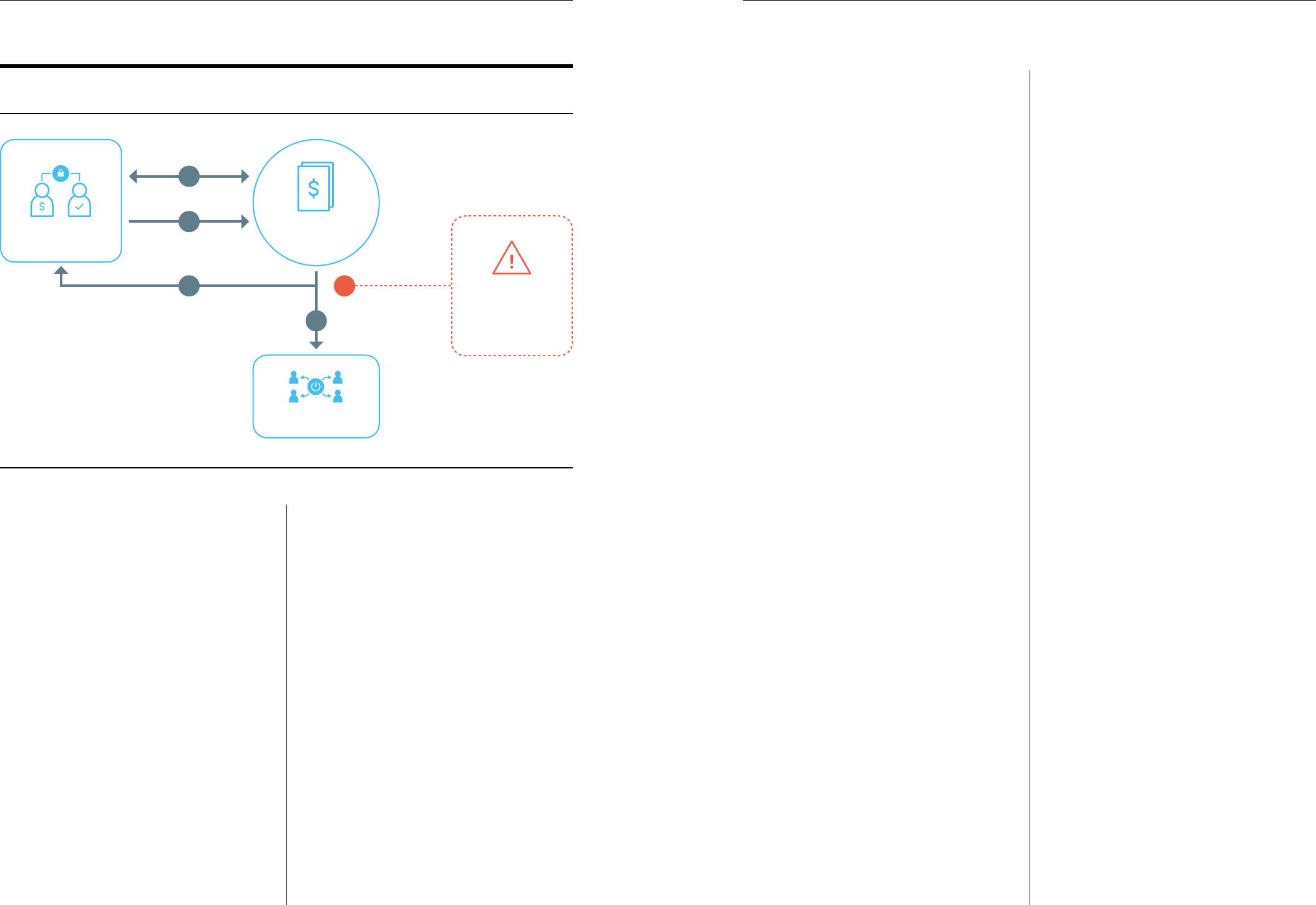

Figure 1 provides a pictorial overview of blended

nance with regards to delivering SDG7 in displacement

settings.

3. Blended nance

3.2. What is the role of blended

nance?

The role of blended nance is to increase returns and/or

lower risks for a commercial entity, which in turn allows

it to mobilise private capital to develop markets it would

not normally enter (WEF & BSG, 2019). In providing an

improved risk-return proposition for the private sector,

blended nance can help bridge funding gaps as the

private sector invests its own money into the solution.

At present there is no estimate on the investment

potential of the private sector for energy projects in

displacement settings. It has, however, been noted that

the impact investment market, who tolerate higher risks

and below-market returns to generate positive social

and environmental impacts, equated to approximately

$715 billion at the end of 2019 (WEF, 2021).

3.3. Why is blended nance

relevant to humanitarian energy

programming?

Blended nance was rst considered as a tool to ll the

funding gap associated with delivering the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs), as most of the nance

ow was through intergovernmental mechanisms,

multilateral grants and bilateral cooperation, which was

not enough to achieve the SDGs (United Nations, 2021).

Blended nance is, therefore, seen as a mechanism

to mobilise private sector investment to support the

delivery of the SDGs.

The rationale behind blended nance is to support

projects with potentially high social benets, which

would not obtain traditionally funding on commercial

terms due to the perceived high risk of operating in

such contexts (WEF & OECD, 2015). Humanitarian

actors are therefore interested in blended nance due

to its ability to mobilise private sector investment in

delivering long-term, sustainable solutions in what are

perceived to be high-risk settings while addressing their

own funding gap.

With respect to energy programming in displacement

situations, blended nance is a mechanism that can

leverage the mobilisation of private capital through

grant funding, which, when combined, can deliver

sustainable energy solutions in emerging or frontier

markets that exist in and around many displacement

settings.

3.4. What does blended nance

look like?

As outlined by the Organisation for Economic Co-

operation and Development (OECD) and the World

Economic Forum (WEF), blended nance can include

one or more of the following nancial support

mechanisms:

1. Direct funding for the removal of commercial

barriers;

2. Technical assistance;

3. Risk transfer mechanisms; and/or

4. Market incentives.

A summary of each mechanism in presented in Table

1 and an overview of each, including examples from

humanitarian energy programming, is provided in

Chapter 4.

No one blended nance solution, however, will t all

situations. Therefore, the structure of a particular

blended nance instrument must be specic to the

aims, nancial needs, delivery model, and risk prole

of the programme it aims to support (Cohen & Patel,

2019).

3.5. When and how to use blended

nance solutions

Blended nance should only be used in situations where a

market failure prevents traditional market development

by the private sector, which results in humanitarian,

development, social and/or environmental impacts that

outweighs the expected nancial returns of the private

investors supporting project. It is, therefore, crucial that

the nancial package offered to the private sector is

not greater than that deemed necessary to induce the

intended investment. This approach is referred to as

the minimum concessionality principle (OECD, 2020

1

).

To assess whether blended nance is needed and

how it can be effectively structured, it is essential to

understand the restrictions and market failures and

the sectoral, country and humanitarian context, and

to articulate how blended nance is supporting the

creation of markets or is helping them move toward

commercial sustainability (IFC, 2018). As a result, it

is important to ensure the blended nance solution is

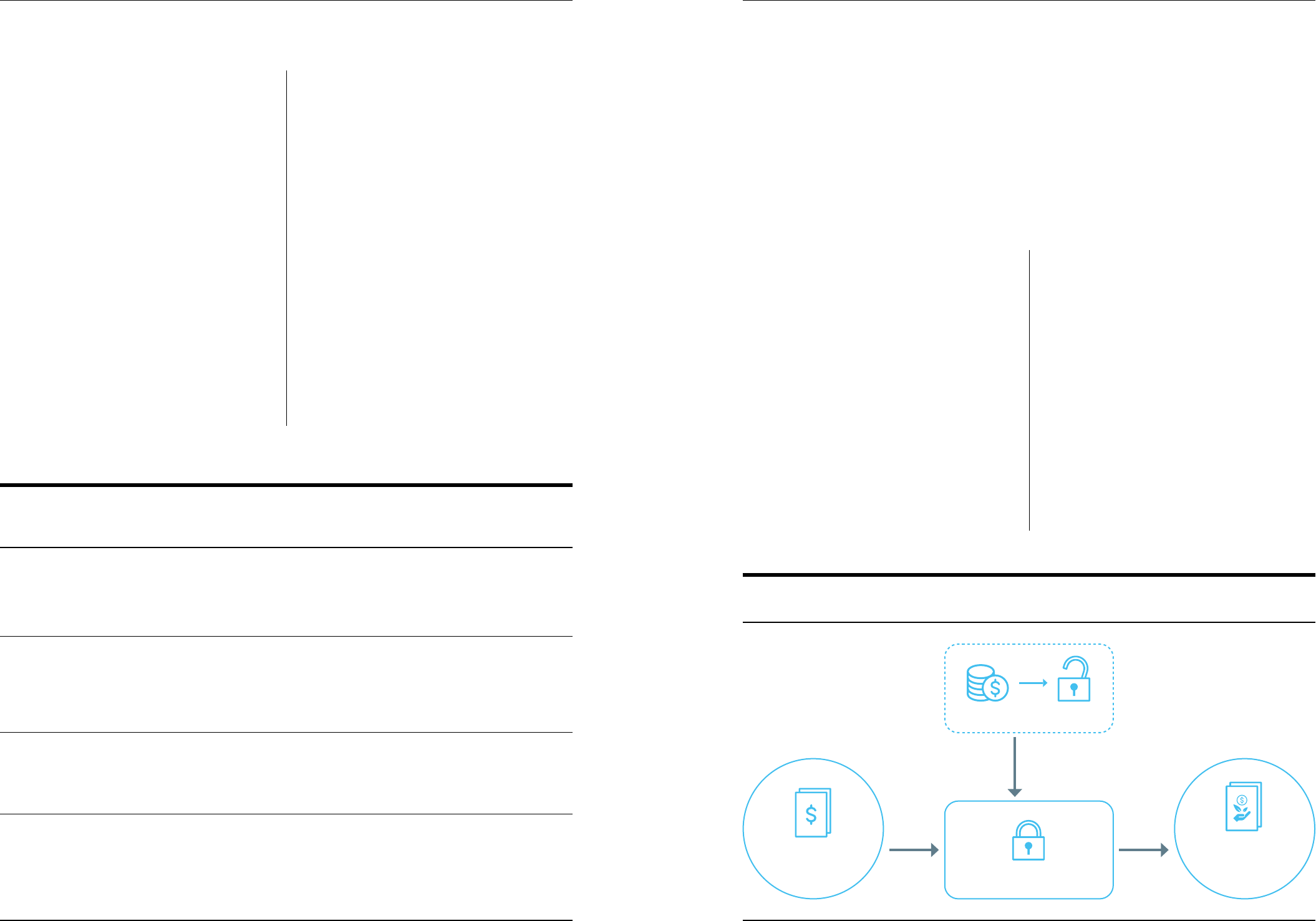

Figure 1: Overview of Blended Finance in Delivering SDG7

Adapted from OECD 2020

Financing sources Financing structure Use of nance

Mobilising /

Catalysing

In Displacement Settings

Non-concessional

Concessional /

Non-concessional

Humanitarian /

Development/

Philantropic

Finance

Commercial

Finance

Blended

Finance

Transactions /

Approaches

Blended Finance Solutions for Clean Energy in Humanitarian and Displacement Settings

1110

4. Blended nance solutions for energy programming in displacement settings

Table 1: Summary of Blended Finance Mechanisms

Adapted from WEF 2015

Direct funding for the

removal of commercial

barriers

Direct funding is provided to unlock a barrier that is preventing an otherwise

commercially viable project from commencing. Direct funding is in effect a grant but

unlike traditional grants the aim of the one-off donation is to create a commercially

sustainable business by removing an identied market barrier.

Technical assistance Technical assistance addresses risks in new, uncertain and fragmented markets

for investors. Costs and risks associated with exposure to new markets, technical

uncertainty, and the inability to build a pipeline can be reduced, lowering the high

transaction costs for investors and reducing operational risks which often dissuade

a commitment of funds.

Risk transfer

mechanisms

Risk transfer reduces specic risks associated with a transaction. This mechanism

provides direct compensation or assumes losses for specic negative events,

addressing the concern of private capital providers to ensure their capital can be

preserved related to project/company specic risks.

Market incentives Market incentives address critical sectors that do not support market fundamentals.

This helps new and distressed markets that require either scale to be commercially

viable or reduced volatility, by providing xed pricing for products in order for private

capital to justify committing to the sector.

designed to meet the identied challenge or challenges

and does not provide nancial support to commercial

risks that can be addressed by the private sector alone.

It is also noted that blended nance should only be used

to address temporary challenges in the marketplace.

For instance, where an initial push to provide a ‘safe’

operating space is required, from which the private

sector can build a self-sustaining commercial presence

that requires no additional concessional funds.

3.6. Blended nance, subsidies

and policy reform

A subsidy is dened as a direct or indirect payment

to individuals or commercial entities that remove a

‘problem’ to promote a social good or an economic

policy. In economic terms, a subsidy is used to offset

market failures and externalities in order to achieve

greater economic eciency (Investopedia, 2021). As

such, it can be argued that blended nance is a form

of subsidy.

Financing on commercial terms should, however, always

be the preferred option to avoid distorting markets

or creating private sector dependence on subsidies.

Blended nance is, therefore, not the solution to long-

term structural issues where permanent subsidies are

called for. Nor is it the solution for inadequate policies

where policy reforms are required (IFC, 2018).

3.7. Supporting mechanisms

Climate funds and carbon nancing can be used to

support blended nance initiatives in humanitarian

situations. In addition, cash-based interventions,

end-user nance and payment systems can play an

important role in supporting the introduction of private

sector solutions to displacement settings. However,

they usually require a long-term approach that many

humanitarian operations cannot commit to. They are,

however, subject matters in their own right and, as

such, it is envisioned that these topics will be covered

by the Global Platform for Action on Sustainable Energy

in Displacement Settings (GPA) in future reports.

The following chapter provides an overview of the four

blended nance mechanisms noted in Section 3.4.

The overview includes a summary of the mechanism,

how it works, its pros and cons, its relevance to energy

programming in displacement settings, and examples

of relevant projects; highlighting lessons learnt.

4.1. Direct funding for the removal

of commercial barriers

4.1.1. What is it and how does it work?

Funding is provided by a donor to a project to unlock

a barrier that is preventing an otherwise commercially

viable project from starting. The direct funding is in

effect a grant, so does not have to be paid back, but

unlike traditional grants the aim of the one-off donation

is to create a commercially sustainable business by

removing the identied barrier, as noted in Figure 2.

Direct funding should only be used if there is a clearly

identiable barrier, which has been identied during the

baseline survey and is recognised as the main barrier to

an energy programme.

4.1.2. How can it be applied to

displacement settings?

Barriers to entry that are relevant to displacement

settings could include costs, amongst others,

associated with construction, logistics, technology,

appliances and import taxes for project infrastructure.

As an example, an energy service company could have

a commercially viable business to sell electricity to a

4. Blended nance solutions

for energy programming in

displacement settings

Commercially

Viable Project

Commercially

Sustainable

Business

Financial Barrier

Donor

Direct Funding

One-off donation unlocking an

identied nancial barrier

Figure 2: Overview of Direct Funding Mechanism

Blended Finance Solutions for Clean Energy in Humanitarian and Displacement Settings

1312

4. Blended nance solutions for energy programming in displacement settings

humanitarian actor from a solar plant that the energy

service company will own and operate. However, before

being able to use this electricity, the humanitarian

partner would need to invest in upgrading their electrical

wiring system. This project attribute is a nancial hurdle,

which - if incorporated into the business model – could

make the project more expensive than an existing

diesel-based solution, preventing the humanitarian

actor from transitioning to a cleaner source of energy. A

direct payment from a donor could, however, cover that

cost of the wiring upgrade and unlock a commercially

viable activity, that has development, humanitarian,

social and/or environmental benets. Other project

attributes associated to decarbonising activities that

could be supported by a one-off grant could include:

● Preliminary works associated with:

● Upgrading existing electrical cabling within the

building and the extension to the new solar

plant;

● Strengthening roong or foundations to

support the solar solution;

● Moving existing infrastructure to make space

for the solar solution; and/or

● Replacing existing equipment with more

energy-ecient solutions, such as energy

ecient appliances, air conditioning units,

lighting, etc., which in turn would reduce the

size of the solution and reduce costs.

● Moving and transporting high-value goods:

● Over long distances and through terrain, where

there is a signicant risk of goods becoming

damaged, and insurance is unavailable or too

expensive; or

● Through conict zones, where there is a

signicant risk of goods becoming damaged

or stolen as a result of an ambush.

● Technological solutions, such as battery storage

in areas where alternative emergency back-up

solutions are essential but not readily available,

e.g. diesel supply is sporadic and limited.

● Appliances, which once distributed, allow the

private sector to sell services, including electricity

and fuel, to the end-user.

● Taxes associated with importing project

infrastructure into a country, which only requires a

single payment.

Similarly, barriers to household cooking projects could

include the cost of a vehicle for distribution, a safe storage

compound for a fuel, the initial cost of an appropriate

cook stove, training technicians and users, etc.

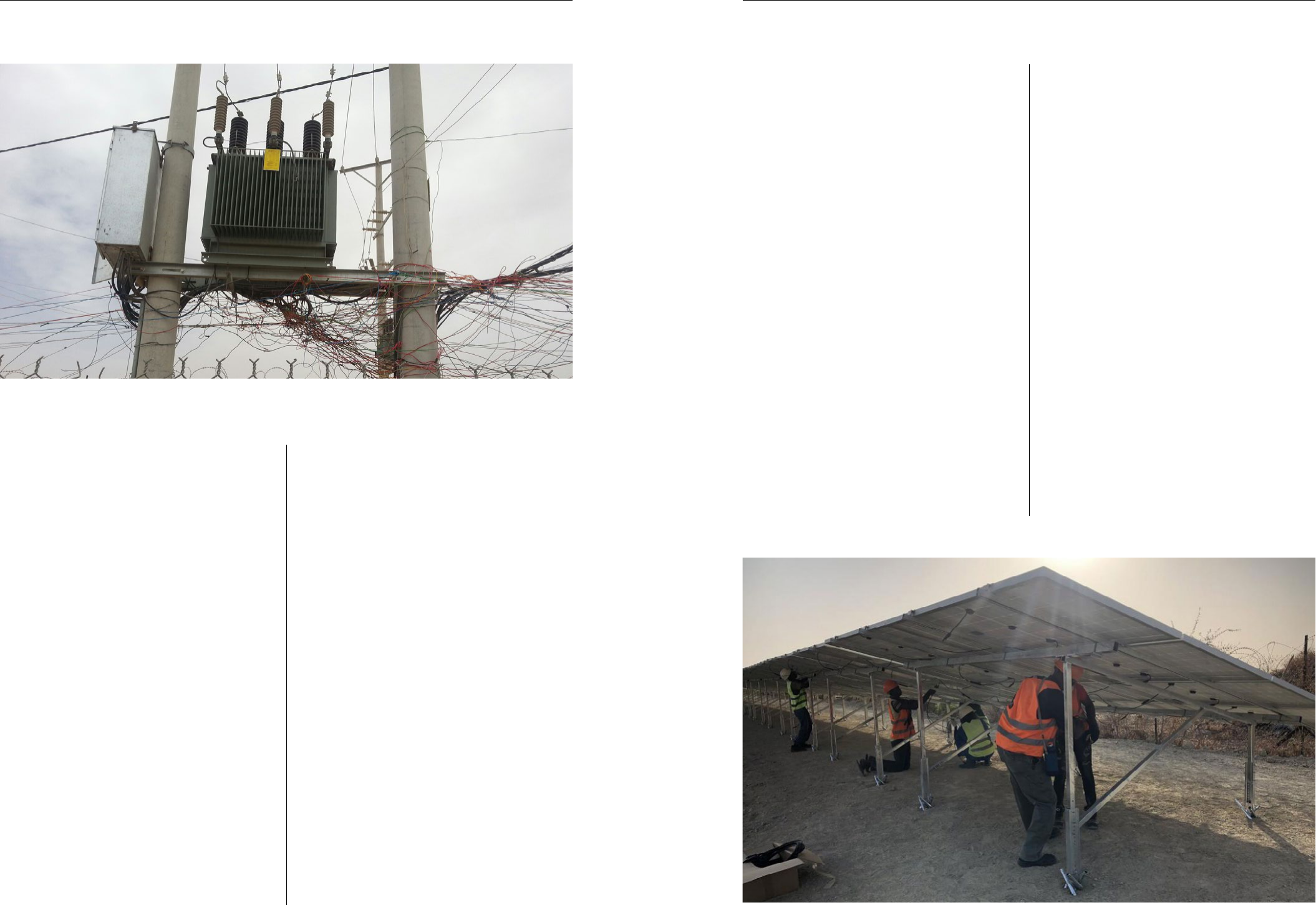

Figure 3: Wiring from the main cables without protection. Photo copyright: UNHCR / Yanal Almadanat

4.1.3. Example project: Humanitarian Hub

in Malakal, South Sudan

The signicant capital investment costs of launching

new clean energy access projects in displacement

settings are often the most challenging hurdle and

can keep a project on hold until appropriate funding

is found. The sourcing of high-quality equipment and

technical expertise in remote areas, or the logistics

and delivery of materials through high-risk areas

(sometimes via helicopter or convoy), can signicantly

increase the capital needed. In some cases, these start-

up costs can be prohibitive.

One such example involved an energy transition project

at the Humanitarian Hub in Malakal, South Sudan,

which is managed by the International Organisation

for Migration (IOM). The Hub hosts about 300

employees from 34 organisations who are supporting

the nearly 30,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs),

host community members and returnees affected by

years of severe conict. As is the case in many similar

remote hubs, the existing energy infrastructure relied

exclusively on diesel-powered generators, leading to

fuel supply risks and lack of autonomy, impacting local

air quality, noise, and contributing to permanently high

energy costs as well as carbon emissions (Scatec

Solar, 2020).

When IOM examined the possibility of transitioning

the facility to run on solar, instead of opting for the

traditional donor-funded capital investment model, they

decided to sign an energy service agreement to reduce

the level of their own capital investment. This contract,

subject to a condentiality agreement, allowed IOM to

purchase energy-as-a-service from Scatec Solar, the

project developer and independent distributed power

producer, who installed the 700 kWp solar photovoltaic

system (IOM, 2020).

As part of the terms of the deal, IOM had to cover a

portion of the initial hardware and installation costs

and then pay for the solar panels and batteries for the

duration of their operations in Malakal. The cost were

to cover commercial barriers to the project. Thanks to a

donor grant of 300,000 GBP from the UK’s Department

for International Development (DFID, now FCDO), the

project was greenlighted and completed in June 2020.

The Malakal project accounts for an 80% reduction

in the Hub’s consumptions of diesel fuel (IOM, 2020),

equating to a saving of around 800 litres per day,

or 292,000 litres per year (equivalent to a saving of

approximately 76 tonnes of CO2 per year), resulting

in annual energy savings of approximately 18%. It is

believed that further cost savings could have been

achievable if a suitable de-risking mechanism was

available to de-risk the termination clause within the

long-term agreement between the two parties (see

section 4.3.3).

Figure 4: Final stages of the solar power plant installation at the Humanitarian Hub in Malakal, South Sudan. Photo copyright: IOM 2020 / Omar Patan

Blended Finance Solutions for Clean Energy in Humanitarian and Displacement Settings

1514

4. Blended nance solutions for energy programming in displacement settings

4.1.4. Example project: Commercial

development of an LPG market by UNHCR

Niger

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

(UNHCR) Niger, with approximately 2 million Euros

of funding from the European Union (EU), developed

the SEED programme (Soutien Energétique et

Environnemental dans la région de Diffa), with the

aim of supporting the commercial development of a

regional, self-sustaining LPG market for clean cooking.

The intervention was focussed on the Diffa region

of Niger, where the wider ecosystem is supportive of

blended nance solutions. The Niger government has

afforded refugees with the legal right to work, study,

move freely, access nance and open bank accounts.

In addition, the displaced are fully integrated into local

communities, which also include IDP.

Prior to the SEED programme, households were paying

up to 24 USD per month for rewood; their main source

of cooking energy. Although LPG was available and

cheaper, approximately 10 USD per month, households

could not transition to LPG as a cooking fuel, as the

cost of the LPG kit (rst cylinder, gas regulator and

cookstove) was too high. The cost of the LPG kit was

approximately 40 USD, around 80% of the maximum

monthly household income of 50 USD per month

(UNHCR, 2017).

The SEED programme used the EU funding to purchase

25,000 LPG kits and distribute them freely to the most

vulnerable families in Diffa, together with vouchers to

rell the 6-kg LPG cylinders eight times, enough for

an average-sized household to cook with LPG for ve

to six months. By distributing LPG kits to vulnerable

households, UNHCR unlocked the barrier to entry and

created a commercial demand for cooking fuel. The

commercial demand was met by SONIHY, a Nigerien

gas company. SONIHY also invested 1.5 million Euros

in the scheme to construct ve new 10-tonne lling

stations, to service 30 new LPG selling points across

the region. UNHCR Niger also acted as a reference to

support SONIHY’s negotiations with a local bank to

obtain loans for the required infrastructure (Patel &

Gross, 2019).

As a result of economies of scale, through the SEED

programme and SONIHY investment in infrastructure,

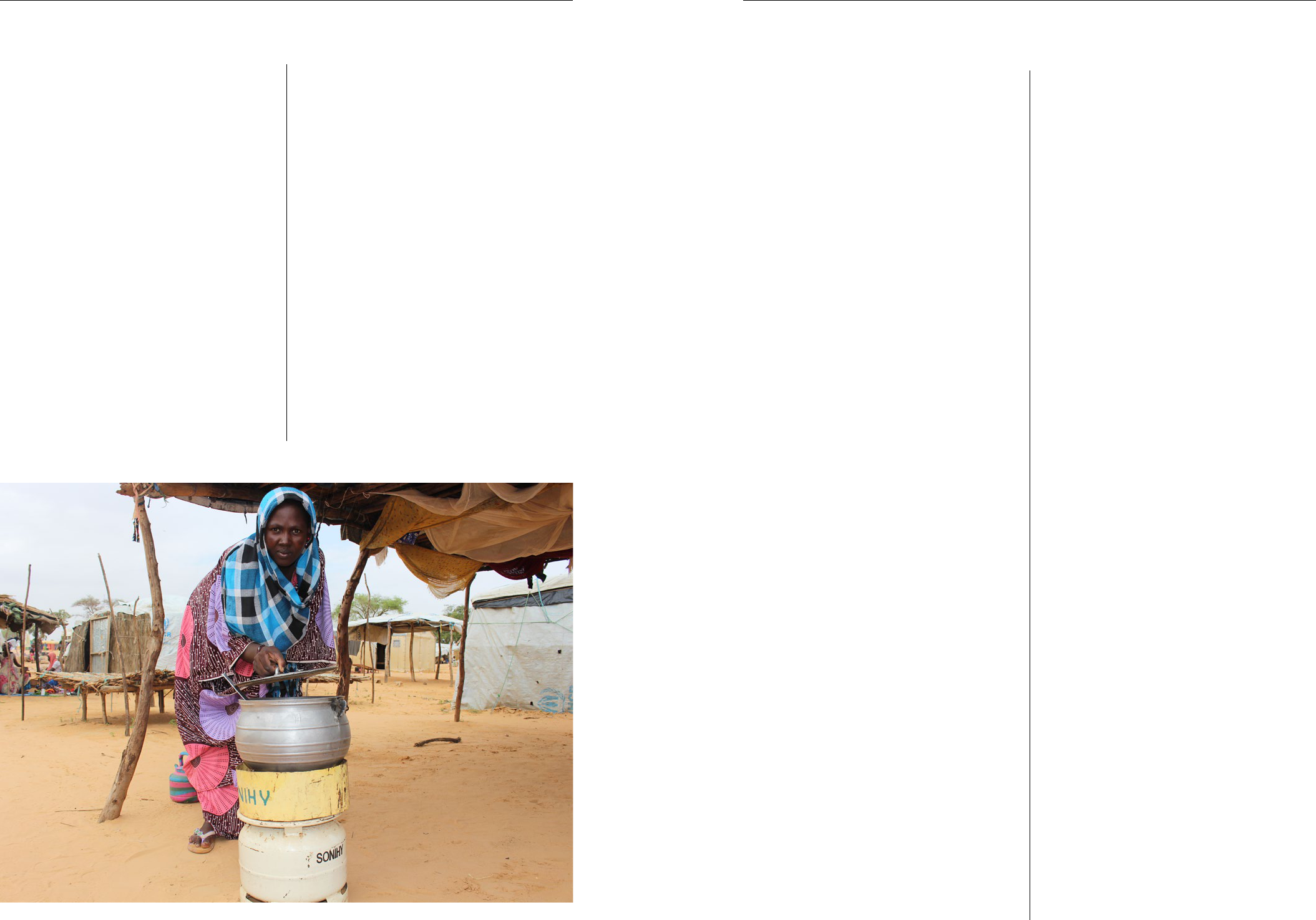

Figure 5: Women refugee in Abala (Tillabery). Photo copyright: UNHCR/Boubacar Younoussa Siddo

the price of LPG has fallen from approximately 10 USD

per 6-kg cylinder to 3 USD per cylinder. An average family

now pays between 3 USD and 5 USD per month on energy

to meet its cooking needs. This cost reduction has

improved the sustainability of the LPG market beyond

the initial UNHCR subsidy period, with 70 per cent of

the 25,000 UNHCR-supported households continuing to

purchase LPG after their initial vouchers had been used

up. The low price of LPG has also attracted between

4,000 and 5,000 new LPG customers in the region who

were not SEED beneciaries (UNHCR, 2017).

Sellers of rewood who were negatively affected by

the fuel-switching programme were compensated

through cash or redeployed into the LPG supply chain

by opening small retail shops or supporting the delivery

of LPG with donated donkeys and carts.

Within 15 months, the total amount of EU funding for

SEED was recovered in savings from fuel purchases

by people living in the region. This household income

boost also supports other donor investments in

livelihood-improvement activities (UNHCR, 2017).

A number of project-specic lessons learnt have been

documented, which include:

● The most vulnerable households struggled to pay

the 3 USD for a 6-kg cylinder rell but could have

beneted from a smaller 2.5-kg cylinder bottle.

● Many of the 30% of households that stopped using

LPG after the SEED programme rells ran out did

so because they were forced to sell their cylinders

to pay for food.

● Development of livelihood opportunities should be

undertaken in parallel to energy access projects

to increase cash ows and the purchasing power

of end-users to increase the sustainability of the

energy projects.

Publicly available information of the lessons from the

UNHCR / SONIHY partnership has not been identied,

although the relationship building between partners is

a key part of any successful blended nance solution.

It would also be of value to understand the medium to

long term impacts of the project.

4.1.5. Lessons learnt

Targeted funding, delivered at the right moment, can

sometimes unlock a commercially viable project that

has a long-term impact. Direct funding could also be

used to kickstart local market demand for certain

energy products or services (e.g. clean cooking fuels)

by overcoming the initial capital investment hurdle.

It is noted that the successful outcomes of the project

examples were supported by:

● Accurate and relevant data on energy demand and

market dynamics was available.

● There was a clear economic model to help support

the transition of an existing energy customer to a

cleaner energy solution.

● Strong government support, with regards to the

cooking project in Niger.

● Relevant skills were available to review the project’s

commercial viability and ensure the sustainability

of the energy intervention.

● Donors were willing to act outside of the box.

● Internal champions who believed in the projects

and can advocate for a new way of working.

While each of the projects is a one-off piecemeal

solution, the solutions could be replicable in similar

environments, especially the example associated

with decarbonising energy infrastructure. Although

the condentiality agreement between the parties

is a challenge to discussing the business case and

identifying possible improvements to the approach.

Based on the above, however, a specic fund aimed

at identifying and unlocking commercial barriers in

displacement settings would prepare the ground for

large scale interventions.

4.2. Technical assistance

4.2.1. What is it and how does it work?

Technical assistance is a mechanism that can attract

private nance to humanitarian energy projects by using

‘in-kind’ technical expertise or a ‘technical assistance

grant’ to address knowledge gaps. It can be directly

incorporated within a nance solution or operate as a

discrete service.

Technical assistance can take the form of advisory

and consulting services for project preparation. It can

also include operational assistance, skills training,

knowledge sharing, and other professional services,

such as legal, nancial or procurement assistance to

improve the business viability of the project and thus

enhance its investment performance (IDFC, 2019 and

OECD & WEF, 2015).

Blended Finance Solutions for Clean Energy in Humanitarian and Displacement Settings

1716

4. Blended nance solutions for energy programming in displacement settings

Technical assistance can only be considered a

blended nance mechanism if the outputs result in

a collaboration with the private sector to deliver an

energy solution.

4.2.2. How can it be applied to displaced

settings?

Expertise and capacity to design and implement modern

energy access and renewable energy interventions in

displacement settings are severely limited; as a result,

energy programmes have not been, and are not always

being, developed by energy specialists. Consequently,

it is rarely possible to get a clear understanding of

the energy needs of displaced communities, energy

programming is slow to adapt to new delivery models,

and there is limited understanding of the inputs and

supporting ecosystem required to move towards

sustainable private sector lead solutions. In addition,

internal support mechanisms tend to be most

responsive to energy programming that has gone on

before, which maintains the status quo.

Designing and implementing a modern energy solution

is complex, requires solid technical, economical

and implementation know-how, and can take up to

ve years to implement. Especially with regards to

undertaking baseline needs assessments and market

surveys, creating partnerships, developing sustainable

delivery models, balancing humanitarian needs against

commercial incentives and nding non-traditional

nancing. As a result, there is a need for energy

specialists across the project spectrum and throughout

the project lifecycle to undertake data collection,

interpret the data to establish the needs, develop

appropriate delivery models, support the creation of

business plans and nancial models, build project

partnerships, provide legal and procurement support,

implement projects, and monitor the results. Rarely can

one ‘expert’ undertake all these tasks, and rarely can

an specialist switch from delivering cooking projects to

developing a solar solution.

Humanitarian actors have, however, relied on

deployment programmes for years, where specialists

in a particular eld can be sent by a deployment agency

to support a humanitarian operation free of charge.

In addition, grants have also been used to pay for

specialist programming support. This can, however,

lead to procurement challenges if the initial support

has been provided by a commercial entity that could

also deliver the solution, as this would be dened as a

conict of interest under UN procurement rules.

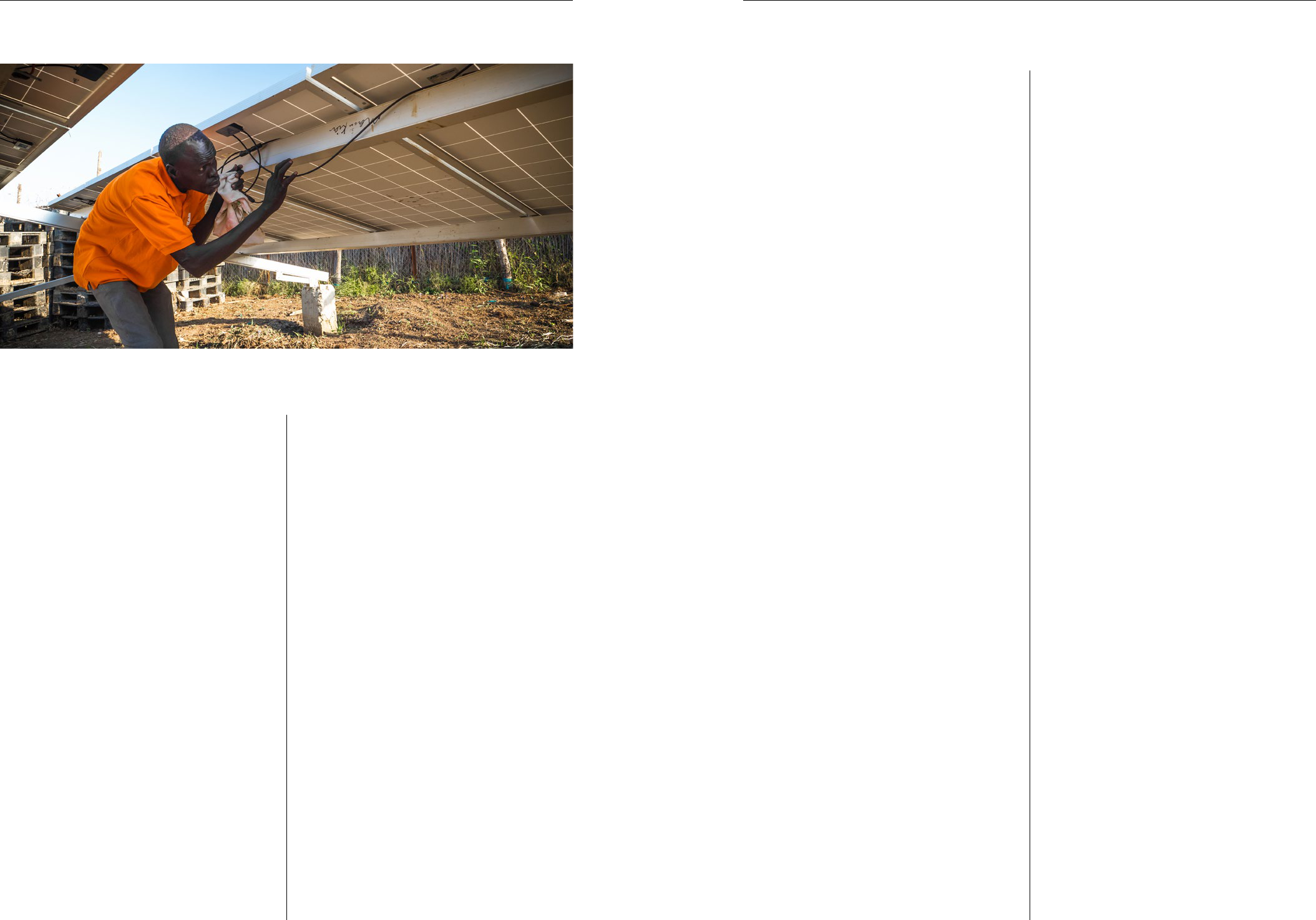

4.2.3. Example project: NORCAP energy

expert deployment programme

NORCAPs clean energy project provides humanitarian

agencies with much needed energy expertise along

three strategic areas: improving energy access (cooking

and electrication) for end users; decarbonisation

of humanitarian responses through increased

renewable energy supply; and global coordination

through dedicated staff to the GPA Coordination Unit

and headquarters of humanitarian agencies. The

programme has been funded by the Norwegian Agency

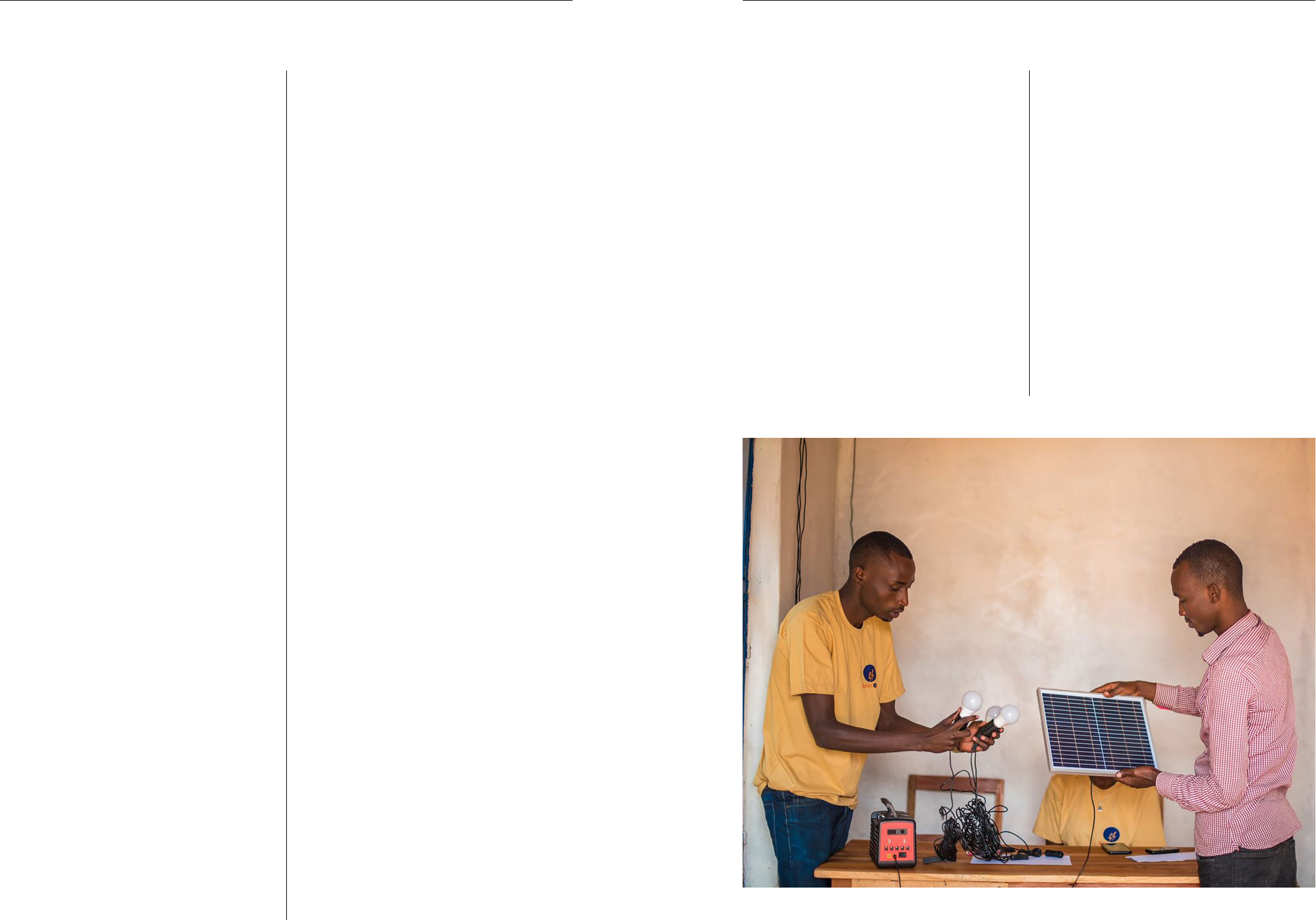

Figure 6: Solar panel wires being checked by the local volunteer Michael Gatluak at the NRC oce in Mankien, South Sudan. Photo copyright: NORCAP/

Iban Colón

for Development Cooperation (NORAD) for four years

to the value of approximately 6,700,000 USD. The

programme is geographically focused on supporting

energy solutions in Africa, given the need and impact.

In 2021, NORCAP provided energy expertise to partners

such as UNHCR, IOM, the Norwegian Refugee Council

(NRC), the World Food Programme (WFP), and the

United Nations Institute for Training and Research

(UNITAR) / GPA Coordination Unit. The experts have a

wide range of experience and expertise in the areas of

bioenergy, solar energy, energy eciency, coordination

and cooking energy and work in several countries in

Africa, including Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and South

Sudan, as well as Jordan and UN agency headquarters

in Geneva and Rome.

NORCAP energy Specialists have undertaken initial

research, data collection, developed proposals and/

or engaged with potential partners on 15 projects to

support private sector lead solutions in displacement

settings.

From its experience in providing energy expertise

to humanitarian partners, NORCAP has noted the

following:

● Humanitarian agencies do not always have the

nancial means to move a particular energy

programme forward once developed by the energy

specialist.

● Not all humanitarian partners are aware of the

benets associated with private sector lead energy

solutions, and it can take a signicant amount of

advocacy to convince partners to transition to new

delivery models.

● A number of NORCAP energy specialists have

taken the GPA Energy Delivery Models (EDM)

Training Programme in order to support the

development of new energy interventions. This has

led to the creation of private sector-lead energy

project proposals that may not otherwise have

been written.

4.2.4. Example project: GIZ Energy

Solutions for Displacement Settings

The Energy Solutions for Displacement Settings

(ESDS) project is one of four components of a global

programme sponsored by the German Federal Ministry

of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) to

support UNHCR in the implementation of the Global

Compact on Refugees (GCR). The focus of ESDS is on

providing sustainable energy solutions to refugee and

host communities in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda to

enhance self-reliance. The 12 million Euro programme

began in November 2018 and is funded until the end

of December 2022. It is understood that a project

extension, along with an additional funding request, is

presently being prepared.

ESDS activities are structured along with three

intervention areas, namely:

● Improving the Policy Framework by working with

policy makers to create the required framework to

implement the GCR and ensure sustainable energy

access for refugees and host communities at a

national, regional and district levels.

● Greening UNHCR Infrastructure, by providing

technical advice to UNHCR to support the

implementation of energy eciency measures

to reduce its diesel consumption and to help its

transition to solar based energy infrastructure via

market-based approaches.

● Improving market-based access to energy by

promoting markets for sustainable energy products

and services for refugee and host communities

in collaboration with UNHCR and private sector

actors (Energypedia, 2021).

The ESDS project team works towards these objectives,

in selected regions, in collaboration with UNHCR

and local and national authorities. ESDS has also

provided technical assistance to UNHCR to support the

nalisation of the technical designs and comparative

nancial modelling for all sites that are to be solarised

under the Green Finance Facility (see section 4.3.3). In

addition, ESDS designed a nancial model adapted to

UNHCR requirements regarding tariff setting and cost

comparison for its solarisation programme.

The project is ongoing, and a mid-term review is

presently being drafted. It is, however, noted that:

● ESDS Uganda is working with Results Based

Financing (RBF) schemes for improved cookstoves

and SHS. Two stove companies and two solar

companies have been contracted, with 2,000 stoves

and 3,750 solar PV systems sold so far (numbers

are currently being veried independently). A

similar RBF scheme is planned for Ethiopia.

● A key learning from the RBF programme is that

although it enhances access to quality products,

the scheme can lead to conict with local

traders who are selling poor quality (sometimes

counterfeit) products.

19

4. Blended nance solutions for energy programming in displacement settings

18

● The programme is only focused on one

humanitarian actor and working in three East

African countries, and, as a result, a structure

dissemination plan for the lessons learnt from the

various programmes and contexts would be of

value to the wider community.

● The technical capacity programme also comes

with its own project funding to support market-

based interventions, which brings additionality to

the programme.

4.2.5. Lessons Learnt

The provision of technical support is probably the

easiest blended nance solution to develop with

humanitarian actors. The results of which can lead to

improved project performance and, therefore, enhanced

investment opportunities.

There are, however, a few important considerations to

use this solution successfully:

● The receiving partner should provide a conducive

support structure (such as technical and personal

support or travel budget for the expert).

● Clear goals and deliverables should be identied

before the deployment with a commitment to apply

them.

● Community engagement, government support and

accountability need to be incorporated into the

project development process to identify the best

solution for a particular context.

● The receiving partner should consider developing

its own energy team at a regional or country level

and reducing the reliance on deployed, short-term

expertise.

● Exchanging knowledge and sharing data are

essential to avoid duplicating efforts and partners

working in the same context should join forces to

complement each other, not compete.

● At the global level, key partners join forces to create

standardised tools that help collect comparable,

quality data based on an agreed set of indicators.

Studies and exploratory work can be undertaken by a third

party, ensuring the independence of the conclusion and

removing potential conicts of interest with a potential

service provider. During long term deployments, which

include a knowledge transfer component, provide an

opportunity to increase local capacity and local knowledge.

4.3. Risk transfer mechanisms

4.3.1. What are they and how do they work?

Risk transfer mechanisms are management tools that

transfer risks to a third party. They involve one party

assuming the liabilities and nancial consequences

of another party, ensuring that any nancing gap that

might emerge is partially or fully covered (Economic and

Social Commission for Asia and the Pacic Committee

on Disaster Risk Reduction, 2017).

Risk transfer mechanisms can either: improve the

credit prole of energy projects or companies who are

seeking project capital; or provide comfort to investors

that they will be able to recover their investment or

absorb smaller losses if events negatively impact their

returns. Therefore, risk transfer instruments shift the

risk-return prole of an investment opportunity, moving

it from un-investable to investable. Two of the most

common types of risk transfer tools are insurance

policies and guarantees (IDFC, 2019).

Insurance policies are contracts issued by a third party

agreeing to make a payment in the case of a particular

event occurring, thus preserving the capital of the

insured party. In this way, they can reduce actual or

perceived risks.

A guarantee is a formal assurance that if an undesirable

event occurs, the guarantor will act on behalf of the

guaranteed party and assumes responsibility. For

example, a guarantee can be used to ensure that if an

individual fails to repay the costs associated with a

solar home system (SHS), the guarantor will cover all

or part of the repayment. Guarantees can help ensure

that commercial entities receive a minimum level of

return or can limit an investor’s losses if a business

opportunity underperforms.

More specically, a guarantee fund is money that has

been set aside and earmarked to underwrite a project

and acts as a formal assurance to the guaranteed party,

in this case the energy solution provider, see Figure 7. As

such, a guarantee fund provides direct compensation

to, or assumes losses for, a specied negative event

and in doing so offsets a nancial risk associated to

an energy intervention, which in turn facilitates private

capital investment.

For example, a loan guarantee is a nancial instrument

aimed at facilitating micro, small and medium-sized

enterprises’ access to formal lending through the

provision of credit guarantees that mitigate the risk of

non-repayment. In practice, a loan guarantee replaces

or reduces the need for other forms of collateral,

resulting in a larger number of enterprises having

The NORCAP expert Geophrey Oyugi

checking the levels of pressure at the

Biogas plant in Malakal – South Sudan.

Photo: NORCAP / Iban Colón

Blended Finance Solutions for Clean Energy in Humanitarian and Displacement Settings

2120

4. Blended nance solutions for energy programming in displacement settings

access to loan facilities. Essentially, a loan guarantee

is a commitment by a third party to cover all or some of

the risks associated with a loan to its client, who may

not have sucient collateral or may not be deemed

creditworthy. As such, if for any reason the borrower

fails to repay, the lender can resort to partial repayment

from the guarantor. Therefore, the loan guarantee

removes barriers to nancing the borrower and permits

nancing on more favourable terms. In addition,

loan guarantees can be used by commercially viable

enterprises but face additional barriers to nancing

(IFAD, 2014).

Insurance policies and guarantees typically require no

immediate outlay of capital, but payment is triggered

when a specied event occurs, which will only happen

in a small proportion of cases. This enables a given pot

of guaranteed funding to be spread across multiple

projects (WEF & OECD, 2015).

4.3.2. How can it be applied to displaced

settings?

In addition to the SHS example noted above,

humanitarian actors, especially within the United

Nations, must include termination clauses within

long term agreements, given the nature of their work.

The termination clause may give the supplier as little

as 30 days’ notice that the humanitarian actor is

intending to cancel the contract. Where the supplier

requires upfront investment to deliver the requested

services, such as constructing a solar system to

supply electricity to a humanitarian agency under a

power purchase agreement, the termination clause is

seen as a signicant contractual risk. As such, it may

be impossible or uneconomic for the energy supply

company to secure nancing for the upfront costs

associated with the solar system, even if the contract

is for a 10-year period. A guarantee underwriting the

termination risk within a contract could therefore

unlock private sector investment in solar solutions for

humanitarian actors.

Similar contractual risks may exist with other electricity

off-takers in displacement settings, such as health

centres, schools and/or commercial entities supporting

livelihood opportunities, which could be de-risked

through guarantees.

A loan guarantee could, for example, reduce the cost of

the goods as a result of reducing the cost of nancing.

This could be signicant, as the cost of nancing has

been identied as a major reason for the rise in costs to

the consumer for a pay-as-you-go solar home system

when compared to the costs associated with buying

the same system up front in a single payment. This

cost differential can result in PAYG SHS costing three

times as much when compared to an outright purchase

of the same system.

In addition, guarantee mechanisms could also be used

to secure loans to individuals in displacement settings

to pay for energy products in instalments (or via

PAYG models) to transfer excessive risk or to support

displaced and host community run energy projects.

On the other hand, there has been little use of risk

underwriting and insurance products as a blended

nance mechanism in displacement settings. The

anticipated high cost of such risk mitigation tools may

limit their role in the future.

4.3.3. Example project: UNHCR Green

Finance Facility

UNHCR’s compounds, premises, and oces generate

greenhouse gas emissions amounting to approximately

97,000 tons of carbon dioxide annually (UNHCR, 2020).

Diesel generators for the production of electricity are a

major source of these emissions. In 2019, the Swedish

International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida)

commissioned a study showing that converting diesel-

based infrastructure to solar energy could signicantly

reduce carbon emissions and costs. As a result, Sida

provided UNHCR with approximately 4 million USD to

establish an internal Green Finance Facility to support

its transition from diesel to solar energy.

The Green Finance Facility will be used as a guarantee

mechanism to de-risk contracts with the private sector,

providing clean energy as a service via long-term power

purchase agreements, which will:

● Allow UNHCR to leverage the technical and

nancing capabilities of the private sector to

undertake the design, ownership, operations, and

maintenance of the solar system.

● Support open and competitive procurement to

encourage fair and effective competition while

seeking the best possible technical solution.

● Support a termination payment in the event that

UNHCR has to terminate the contract(s) before the

end of the payback period.

● Reduce carbon generation at facilities by 60 to

100%, reduce costs by up to 35% and create

commercially viable opportunities for the private

sector in humanitarian settings (UNHCR, 2020).

UNHCR are initially targeting 3 sites; Kakuma in

Kenya and Adjumani and Yumbe in Uganda, following

an expression of interest, which closed in early

2021. The Request for Proposal was issued at the

beginning of September 2021 and will be directed to

preferred bidders who have been identied through the

expressions of interest process.

As the projects have yet to be established under the

Green Finance Facility, there is little to share with

regards to lessons learned, however, it is noted that:

● UNHCR’s energy transition programme, under

the Green Finance Facility and its energy access

programmes, is currently limited to their own

premises (oces). A solution suitable for

energy programmes in displaced or local host

communities (for example, using UNHCR or other

humanitarian agencies as an anchor client) still

needs to be developed.

● Financial guarantee mechanisms within the UN

system must follow UN nancial rules. With the

exception of the International Fund for Agricultural

Development and the United Nations Capital

Development Fund, reportedly, nancial guarantee

mechanisms within the UN are only permitted

when cash reserves match the nancial exposure

dollar to dollar, i.e., the value of the guarantee fund

must match the value of the guaranteed services

(UNDP Global Energy & Finance Advisor, 2020,

personal conversation; UNCDF Investment Lead,

2021, personal conversation).

● The Green Finance Facility is for one agency. Other

agencies have set up similar funds in the past for

other purposes. The existence of multiple funds

across multiple agencies can lead to competition

for donor funding. It would be more resource-

ecient if such a guarantee fund could be accessed

by multiple partners, including organisations

outside the UN.

● In relation to the previous two bullet points, a

global guarantee mechanism has been explored

by the GPA Coordination Unit. The results of the

study suggest a guarantee facility housed outside

of the UN, accessible by all, with 6 million USD of

capitalisation could underwrite 65 million USD

of private investment. This equates to 1 USD

of guarantee underwriting just under 11 USD of

investment (EMRC, Shell & GPA, 2020).

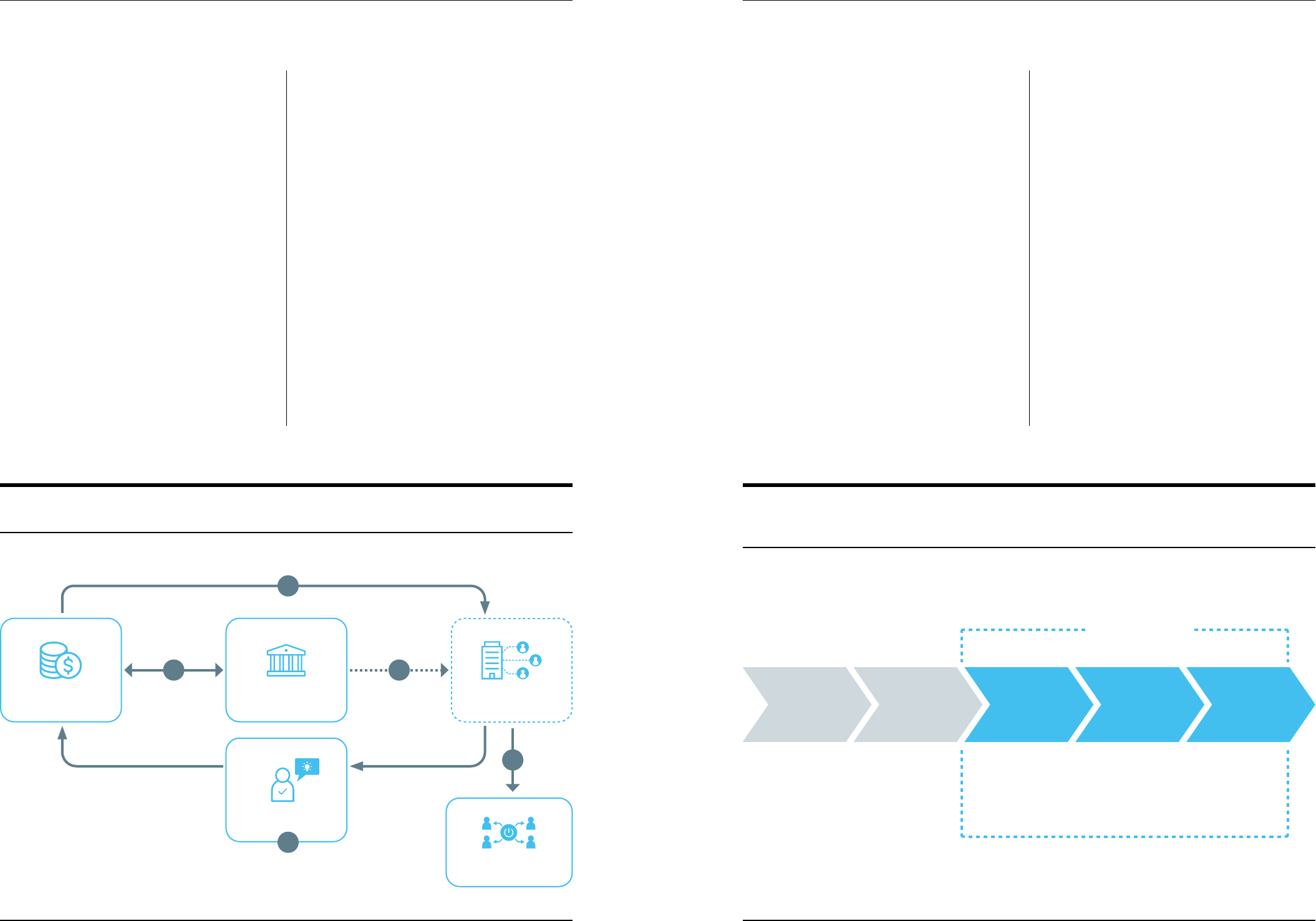

Figure 7: Overview of Guarantee Fund

Commercially

Viable Project

End Users

Guarantor

Potential negative

event or risk that

inhibits a commercially

viable project

Selling goods

and services

Independently veried

underperformance

Guarantee

Agreement

Payment based on

underperformance

1

4

2

!3

Blended Finance Solutions for Clean Energy in Humanitarian and Displacement Settings

2322

4. Blended nance solutions for energy programming in displacement settings

4.3.4. Example project: IOM Research in

Mozambique

In 2020 as part of Shell’s Enter Energy project and its

partnership with IOM, a consulting study done by the

Differ Group assessed the feasibility of setting up a

guarantee fund to support local Distributed Energy

Service Companies (DESCOs) that sell household

energy access products such as solar home systems

(SHS) to customers in displacement affected areas

in Mozambique. The study’s main objective was to

understand whether a particular guarantee mechanism

could overcome the following barriers: uncertainty

regarding the permanence of resettlement areas;

limited DESCO presence in resettlement areas; sparsely

populated rural and resettlement areas; high working

capital requirements for the DESCOs; and high capital

cost of productive use equipment which makes it risky

to sell on PAYG (Differ, 2021). The key ndings of the

study are noted in the proceeding paragraphs.

For instance, a product default guarantee mechanism

would compensate the DESCO for a pre-agreed share

of their nancial losses in the event where a customer

stops paying for a PAYG product during the repayment

phase (e.g. after three months of non-payment, and

lasting up to six months), also preventing the need

for product repossession. While this mechanism

would give such customers increased time to restart

their payments, which might help those with seasonal

revenues bridge to the next harvest season and avoid

repossession of the system, it also creates a strong

perverse incentive for customers to simply stop

making their monthly payments while continuing to use

their SHS. This would result in a very high likelihood of

rapid depletion of funds. Furthermore, the measuring,

reporting and verication (MRV) of this scheme would

be very challenging in practice as it would require

checking that the product was installed, that payments

were not made for the past three months, that support

was not already claimed for the device and that once

the guarantee support is provided, that the DESCO

would not be double compensated in the event that the

customer resumes making payments.

Lack of working capital was identied by some DESCOs

as a barrier to entering the SHS market in resettlement

areas. A working capital loan guarantee mechanism

could be used to create a fund, through the help of a

nancial institution/ intermediary to provide a credit

backstop in the event that DESCO defaults on their

working capital loan to their creditor. This scheme

has a much lower risk of being abused due to adverse

incentives and has a low likelihood of resulting in

depletion of funds.

A portfolio guarantee mechanism is similar to the

product default guarantee in that it absorbs a portion of

Figure 8: Energy assessment conducted by IOM Energy Ocers in a resettlement site in Sofala Province, Mozambique. Photo copyright: IOM 2020 /

Isaac Mwang

the risk of high customer defaults in resettlement areas.

It is, however, applied at the portfolio level, meaning

that it compensates a DESCO for nancial losses if the

average default rate on its entire pool of customers

exceeds the average default rate that it would

normally experience in a given country and covers this

difference. The result should be that the companies can

operate under the assumption that resettlement areas

perform the same way as the rest of the country and

are a normal part of the business. In terms of adverse

incentives, the scheme could potentially incentivize

DESCOs to sell to anyone regardless of income or ability

to pay, not follow up with delinquent accounts, and then

harvest the guarantee support in lieu of revenue. As a

consequence, there is a risk of fund depletion, which is

higher early on, and then diminishes over time.

The minimum income guarantee mechanism is

envisioned to support the sale or leasing of productive

uses equipment, which are usually outside the scope of

PAYG schemes due to their high capital costs and risks

of default. A minimum income guarantee could be used

to supplement customer repayments (which could

uctuate depending on seasonality or other factors)

and ensure that the DESCOs stay above the minimum

threshold of commercial viability in terms of income.

A return and default results-based framework

incentivises the return and repossession of unutilized

equipment, which could lower costs of defaults for the

DESCOs and make their operations more sustainable.

The scheme could help to create an ecient

secondary market for refurbished systems no longer

in use, while also potentially creating local employment

opportunities and kickstarting a circular economy

focused on the recycling of used systems. The scheme

would give already non-paying customers an incentive

to return (and received a deposit back) instead of

keeping unused equipment, especially if they are no

able to manage the payments. Less stranded assets

and electronic waste is an additional positive impact of

this mechanism.

4.3.5. Lessons Learnt

Risk transfer mechanisms can make energy projects

commercially viable in humanitarian settings by shifting

the risk-return ratio and reducing the cost of capital.

Risk transfer mechanisms can be tailored to address

specic problematic risks for a given type of project,

ensure funds are channelled to where they are

most needed, thereby unlocking a hurdle preventing

private sector engagement. In addition, a single local,

regional, national, or global guarantee can enable the

development of more than one project.

Guarantee mechanisms can, however, generate moral

hazards and adverse incentives that must be considered

in the project’s design, implementation, and MRV

phases. The biggest adverse incentives are: non-paying

customers having little incentive to resume payments;

over-incentivising product repossessions (where

DESCOs rush to seek compensation for delinquent

contracts); trouble targeting the right populations (e.g.

IDP versus host community); underreporting successes

(especially where system sales data are not used as

a baseline); repeatedly reporting the same defaults;

and overstating the level of defaults in the case of

portfolio approaches. These adverse incentives can be

partially counter-balanced by effective MRV programs.

In practice, however, MRV is also costly and presents

its own challenges in terms of ensuring 100 percent

accuracy of results.

In general, guarantee mechanisms are fairly complex

and require signicant time and investment to set

up, with engagement from multiple stakeholders to

ensure a context-appropriate design and prudent

implementation strategy. If, however, structured and

administered well, they do have the opportunity to

remove specic barriers or risks from the market

and attract new market participants to otherwise

underserved areas.

Loan guarantees lower the risk of lending to small

businesses. However, the primary constraint at the

lender level is the lack of relevant products, trained

staff, and an outreach strategy, which can result in a

block to accessing credit.

Though quite effective for high-risk situations,

insurance mechanisms can be expensive and may not

therefore be applicable or appropriate for all situations.

4.4. Market incentives

4.4.1. What are they and how do they work?

Market incentives aim to support investment with

high-impact outcomes in situations where normal

market conditions do not exist, for instance, in a

refugee settlement. In doing so, they look to create

commercial markets where they did not originally

exist by encouraging capital to move into areas

with humanitarian and/or development needs. Such

incentives are particularly important to markets

that require innovative solutions to deliver impactful

products and services.

Blended Finance Solutions for Clean Energy in Humanitarian and Displacement Settings

2524

4. Blended nance solutions for energy programming in displacement settings

Market incentives are generally structured as a

guarantee for payments against products and services

based on performance or supply, or in exchange for

upfront investment in new or distressed markets.

Examples include Results Based Financing (RBF),

impact bonds and challenge funds, among others. The

following sections provide an overview and examples

of RBF, impact bonds and challenge funds.

4.4.2. Results Based Financing

WHAT IS IT AND HOW DOES IT WORK?

Results Based Financing (RBF), commonly referred to

as ‘payment by results’ is an umbrella term referring to

any program or intervention that provides rewards to

individuals or institutions after agreed-upon results are

achieved and veried (World Bank, 2019).

RBF involves three key principles. Firstly, payments

are made only after the results have been achieved.

Secondly, the recipient may independently choose how

to achieve these results. And lastly, an independent

verication of the results triggers the agreed nancial

disbursements (Sida, 2015). The rationale behind

this approach is to directly link nancing with outputs

and outcomes rather than inputs and processes. The

objective is to increase accountability and create

incentives for service providers to improve programme

effectiveness and achieve agreed results while

providing the service providers with the autonomy

and exibility to adjust their project implementation

strategies to deliver the most impact (OECD, 2014).

Therefore, results-based approaches shift the nancial

risk associated with the non-delivery of results from the

donor to the recipient of the funding.

RBF schemes begin with a contractual agreement

between a funder (donor) and an implementing

organisation who both agree on the outputs, outcomes

and impacts that are desired. The implementing party

either launches the program or intervention themselves

or invites third party service providers to participate

in the delivery of the solutions. Once the results are

veried by an independent body, the payment or

incentive is released by the funder to the the service

provider(s) as noted in the contractual agreement. A

pictorial overview of RBF is presented in Figure 9.

In contrast to traditional funding approaches, RBF

can drive innovation that leads to greater impact for

beneciaries and lowers the costs for funders (GPRBA,

2020). It is also regarded as being a reliable nancing

mechanism once its purpose has been clearly dened.

There are many different approaches to RBF, including

output-based aid, outcomes-based aid, and impact

bonds. Impact bonds are discussed in more detail in

the following section. Output-based aid is a nancial

mechanism that aims to increasing access to products,

goods and services that result in changes relevant to

the desired output. It is used in situations where people

are being excluded from basic services because

they cannot afford to pay the full cost of a service or

associated connection fees. Outcome-based nancing

includes mechanisms that tie funding to metrics more

closely related to the ultimate development objective,

i.e., ‘outcomes’ as opposed to intermediary results,

such as system actions, inputs, activities, and outputs.

Figure 10 provides an overview of the triggers for RBF

nancing.

HOW CAN IT BE APPLIED TO DISPLACED

SETTINGS?

Output-based aid could be used to target displaced

household connections to a solar mini-grid or increase

sales of clean cookstoves within a displacement

setting. While outcome-based nancing could be tied

to humanitarian programmes that reduce the amount

of greenhouse gasses, upscale and replicate new

business models or technologies, or reduce household

cost from shifts in spending on cooking fuels.

EXAMPLE PROJECT: SNV NETHERLANDS

Foundation of Netherlands Volunteers (SNV

Netherlands) is a non-prot international development

organisation that was among the rst organisations

to successfully implement RBF schemes to support

modern energy services in displacement settings and

for isolated off-grid communities.

In Mozambique, SNV is leading the implementation

of BRILHO – a ve-year programme started in 2019

to increase energy access. BRILHO’s main goal is to

improve energy access for both people and businesses

within the low-income population, leading to nancial

Results that trigger

disbursments

Financial and

human resources

used

Steps taken or

work performed to

transform inputs

into outputs

Products capital

goods and services

resulting in changes

relevant to outcome

Likely or achieved

short-term and

medium-term

effects

Long-term effects

produced

ImpactOutcomesOutputsActivitiesInputs

Figure 10: Overview of RBF Triggers

Adapted from OECD, 2014

Figure 9: Overview of Results Based Financing

End Users

Funder

Implementing Agency

Independent Verier

Service Provider(s)

Contractual

Agreement

Implementing

Agreement

1 2

Improved

Energy

Access

5

Payment for Results

Verication of Results

4

3

Blended Finance Solutions for Clean Energy in Humanitarian and Displacement Settings

2726

4. Blended nance solutions for energy programming in displacement settings

savings, better well-being and increased livelihood

opportunities. The program is targeting three product

segments: improved cooking solutions, SHS and mini-

grids and hopes to impact as many as 1.5 million

people. To reach this target, BRILHO works with

selected companies to provide a mix of catalytic grants