relevance •

effectiveness

• coordination and partnership • efficiency • national ownership • international cooperation •

managing for results

• sustainability • relevance • effectiveness

coordination and partnership • efficiency •

national ownership

• international cooperation •

managing for results •

sustainability

• relevance • effectiveness • coordination and partnership •

efficiency • national ownership • international cooperation •

managing for results

• sustainability • relevance •

effectiveness •

coordination and partnership

• efficiency • national ownership • international cooperation • managing

for results • sustainability •

relevance

• effectiveness • coordination and partnership • efficiency • national ownership •

international cooperation • managing for results •

sustainability

• relevance • effectiveness • coordination and partnership •

efficiency •

national ownership

• international cooperation • managing for results • sustainability •

relevance • effectiveness • coordination and partnership •

efficiency

• national ownership •

international cooperation

• managing for results • sustainability • relevance • effectiveness

coordination and partnership • efficiency • national ownership • international cooperation • managing for results • sustainability • relevance • effectiveness • coordination and partnership •

efficiency • national ownership •

international cooperation • managing for results • sustainability •

relevance •

effectiveness • coordination and partnership • efficiency • national ownership • international cooperation • managing for results • sustainability • relevance • effectiveness

coordination and partnership • efficiency •

national ownership • international cooperation •

managing for results •

sustainability

• relevance • effectiveness • coordination and partnership •

efficiency • national ownership • international cooperation •

managing for results • sustainability • relevance •

effectiveness •

coordination and partnership • efficiency • national ownership • international cooperation • managing

for results • sustainability •

relevance • effectiveness • coordination and partnership • efficiency • national ownership •

international cooperation • managing for results •

sustainability • relevance • effectiveness • coordination and partnership •

efficiency •

national ownership • international cooperation • managing for results • sustainability •

relevance • effectiveness • coordination and partnership •

efficiency • national ownership • international cooperation • managing for results • sustainability • relevance • effectiveness

coordination and partnership • efficiency • national ownership • international cooperation • managing for results • sustainability • relevance • effectiveness • coordination and partnership •

efficiency • national ownership •

international cooperation • managing for results • sustainability •

INDEPENDENT EVALUATION UNIT

In-depth evaluation of the

United Nations Global Initiative

to Fight Human Trafficking

(UN.GIFT)

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME

Vienna

In-depth evaluation of the

United Nations Global Initiative

to Fight Human Trafficking

(UN.GIFT)

GLOS83

Independent Evaluation Unit

M ay 2 011

UNITED NATIONS

New York, 2011

ii

is evaluation report was prepared by Dalberg Global Development Advisors (www.dalberg.com), an internatio-

nal development consulting rm, in collaboration with the Independent Evaluation Unit (IEU) of the

United Nations Oce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). e evaluation team included the external evaluation

team of Dalberg Global Development Advisors: Veronica Chau, Gaurav Gupta, Michael Tsan, and Tim Carlberg.

e desk research and interviews were supported by a dedicated team of Dalberg researchers and interviewers

including Nupur Kapoor, Chris Denny-Brown, Tarun Mathur, and Vaibhav Garg.

In constructing this report, the many stakeholders who generously gave their time for interviews and electronic

surveys are thanked, as well as the UN.GIFT programme management and sta for their excellent cooperation

with the evaluation team’s data requests.

Independent Evaluation Unit of the United Nations Oce on Drugs and Crime

United Nations Oce on Drugs and Crime

Vienna International Centre

P.O. Box 500

1400 Vienna, Austria

Telephone: (+43-1) 26060-0

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.unodc.org

Dalberg Global Development Advisors

Washington D.C. Oce

818 18th Street, Suite 505

Washington, DC, 20006, USA

Telephone: (+1) 202 659 6570

Telefax: (+1) 202 659 6863

Email: V[email protected] (Lead Evaluator)

Email: Gaurav[email protected] (Project Director)

Email: Michael.T[email protected] (Project Manager)

Website: www.dalberg.com

Independent Project Evaluations are scheduled and managed by the project managers and conducted by external

independent evaluators. e role of the Independent Evaluation Unit (IEU) in relation to independent project

evaluations is one of quality assurance and support throughout the evaluation process , but IEU does not directly

participate in or undertake independent project evaluations. It is, however, the responsibility of IEU to respond

to the commitment of the United Nations Evaluation Group (UNEG) in professionalizing the evaluation func-

tion and promoting a culture of evaluation within UNODC for the purposes of accountability and continuous

learning and improvement.

Due to the disbandment of the Independent Evaluation Unit (IEU) and the shortage of resources following its

reinstitution, the IEU has been limited in its capacity to perform these functions for independent project evalu-

ations to the degree anticipated. As a result, some independent evaluation reports posted may not be in full

compliance with all IEU or UNEG guidelines. However, in order to support a transparent and learning environ-

ment, all evaluations received during this period have been posted and as an on-going process, IEU has begun

re-implementing quality assurance processes and instituting guidelines for independent project evaluations as of

January 2011.

© United Nations, September 2011. All rights reserved.

e designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of

any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any

country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

is publication has not been formally edited.

Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Oce at Vienna.

iii

CONTENTS

Page

Executive summary ..................................................................... vii

Management response

................................................................... xi

Steering Committee response

............................................................ xiii

I. Introduction ............................................................................ 1

A. Background

........................................................................ 1

B. Evaluation scope, methodology and limitations

..................................... 12

II. Major evaluation ndings and analysis

................................................... 17

A. Relevance

.......................................................................... 17

B. Eectiveness

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

C. Eciency

.......................................................................... 47

D. Partnerships, management and governance

.......................................... 49

III. Impact and sustainability

................................................................ 55

A. Impact

............................................................................. 55

B. Sustainability

....................................................................... 55

IV. Case studies

............................................................................. 57

A. Case study: South Asia Regional Conference (SARC)

............................... 57

B. Case study: Serbia Joint Programme

................................................ 63

V. Lessons learned and best practices

....................................................... 67

A. Lessons learned

.................................................................... 67

B. Best practices

....................................................................... 68

VI. Recommendations

...................................................................... 71

A. Interim recommendations and actions taken since October 2010

.................... 72

B. Final recommendations

............................................................. 73

C. Detailed level recommendations

.................................................... 77

iv

Page

Annexes

I. Summary matrix of ndings, supporting evidence and recommendations .......... 85

II. Terms of reference

.................................................................... 95

III. List of persons interviewed

............................................................ 97

IV. Evaluation interview guide sample

.................................................... 103

V. Evaluation survey sample

.............................................................. 105

VI. Mission schedule (Serbia)

............................................................. 117

VII. Mission schedule (India)

.............................................................. 119

VIII. UN.GIFT documents consulted

...................................................... 121

IX. External documents consulted

......................................................... 127

Figures

I. UN.GIFT Logical Framework with pillars, outputs and key activities ............ 2

II. UN.GIFT’s Organizational Structure (June 2010) ........................... 4

III. UN.GIFT’s Organizational Structure (December 2010) ...................... 4

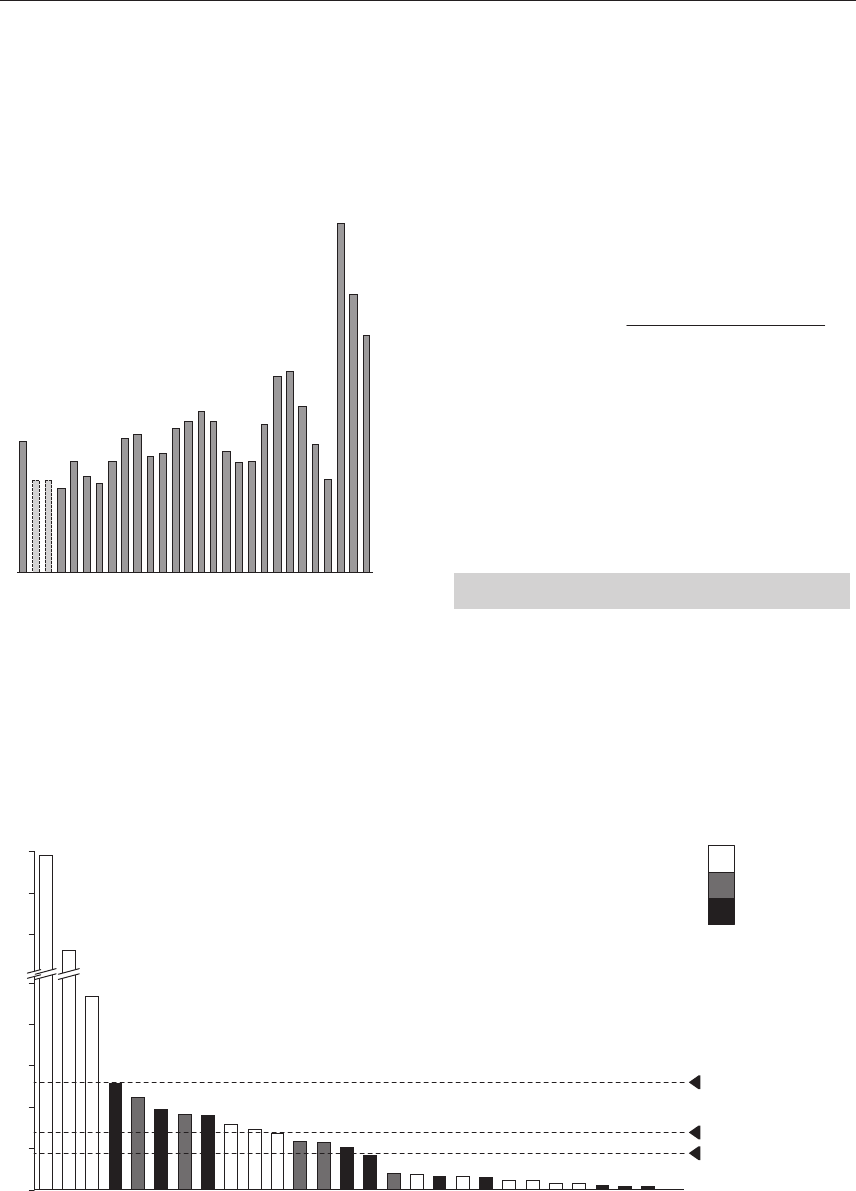

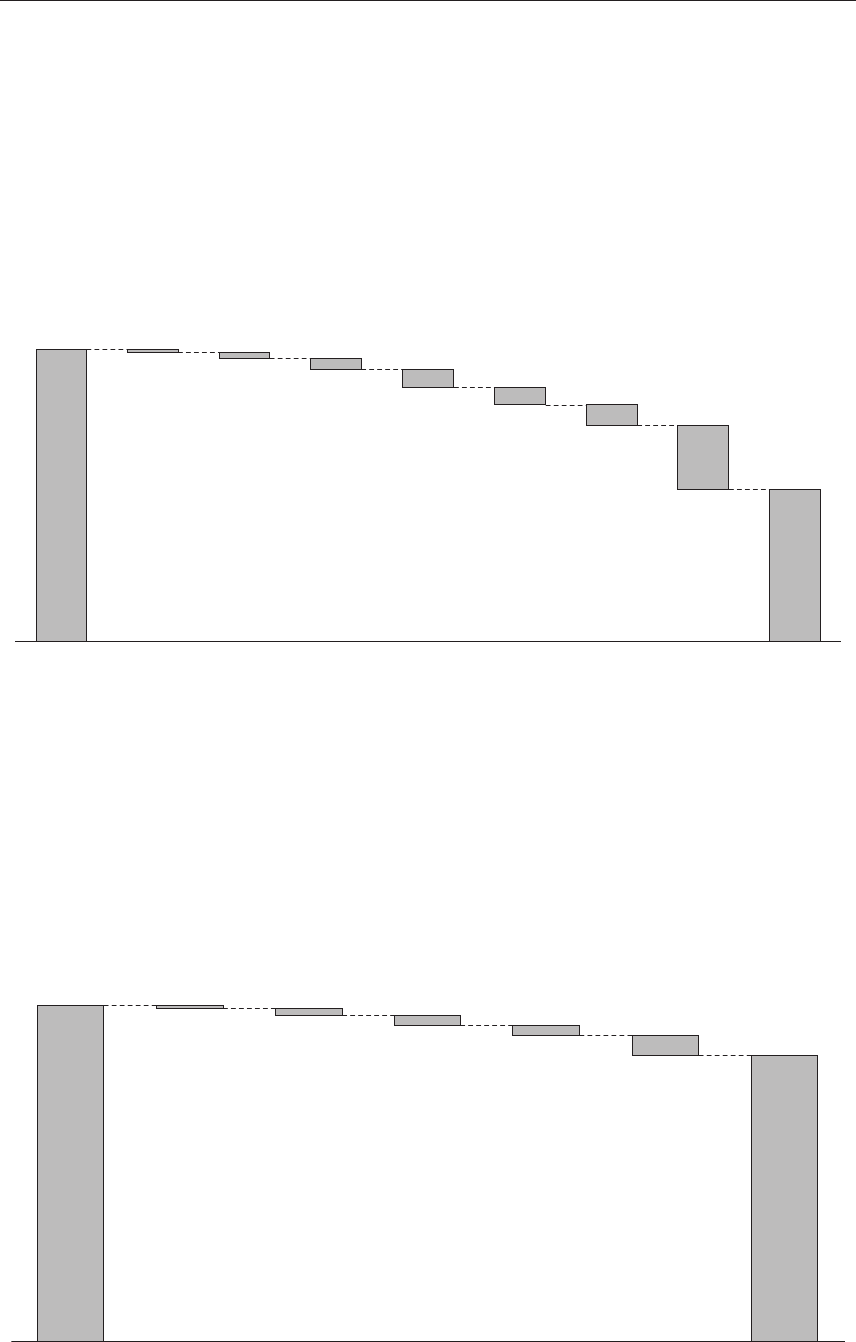

IV. UN.GIFT expenditures (2007-2011) ..................................... 9

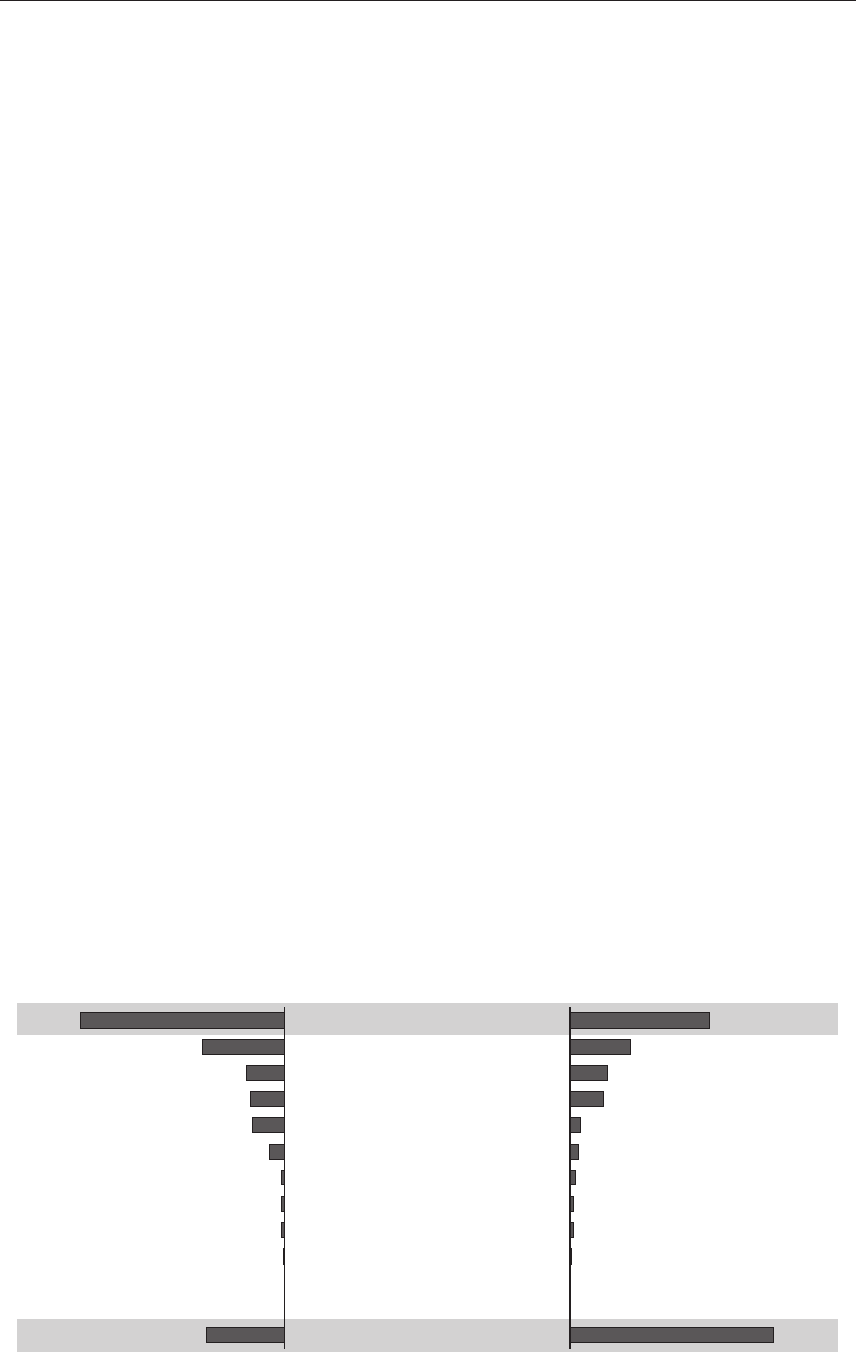

V. Shift of expenditures to capacity-building and victim support after 2008 .......... 11

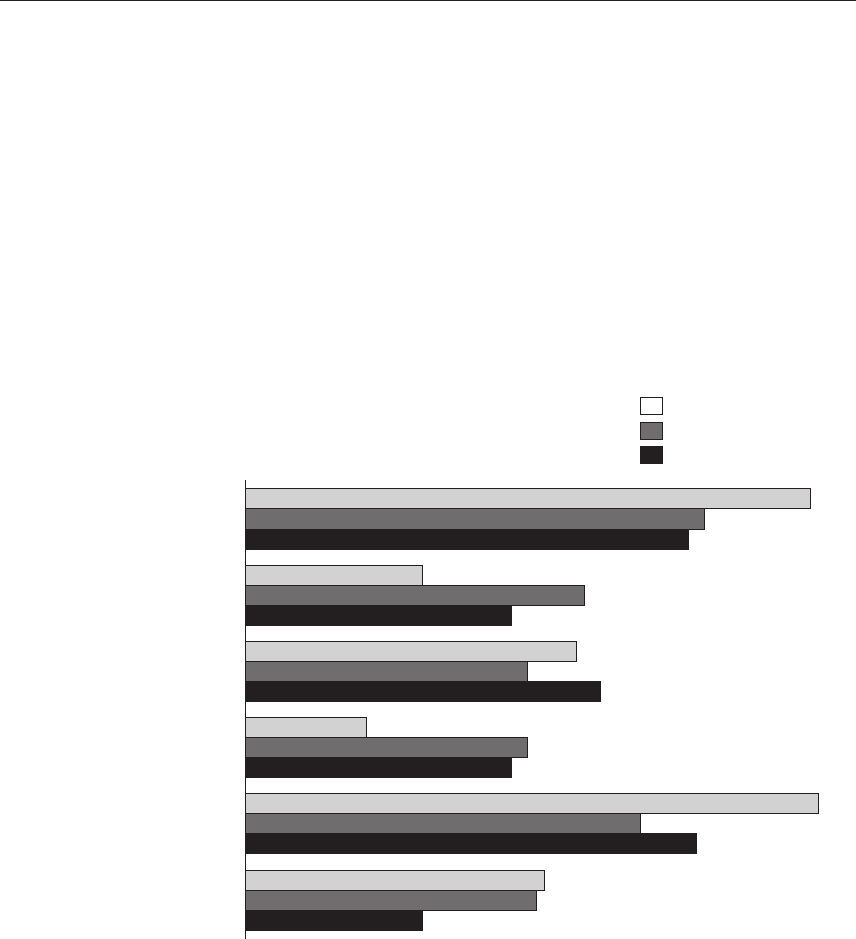

VI. e relevance of the broad UN.GIFT output areas is high ..................... 20

VII. UN.GIFT assessments of AHT needs match perception of external stakeholders .... 20

VIII. UN.GIFT allocation of expenditures to global and regional initiatives ............ 22

IX. UN.GIFT activity mix by output area .................................... 23

X. Overall UN.GIFT eectiveness—contribution towards UN.GIFT outcomes ...... 24

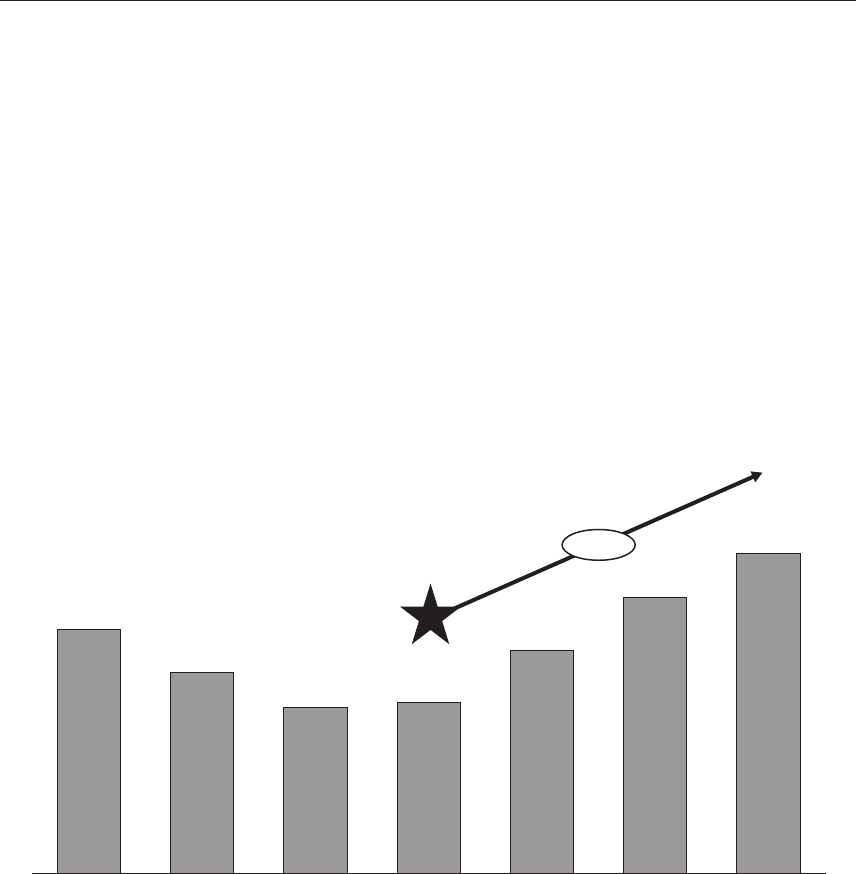

XI. Rise in political commitment at state level ................................. 26

XII. Awareness of human tracking on the internet ............................. 27

XIII. UN.GIFT website statistics (prior to launch of Virtual Knowledge Hub) .......... 28

XIV. Comparison of UN.GIFT PSAs with those of other stakeholders ................ 28

XV. Web mentions and citations of UN.GIFT publications ....................... 29

XVI. Virtual Knowledge Hub website trac (May-November 2010) ................. 31

XVII. End-user feedback on the Virtual Knowledge Hub ........................... 32

XVIII. SGF eectiveness—positive outcomes on many dimensions .................... 45

XIX. UN.GIFT cost eectiveness ............................................ 47

XX. Break-down of Vienna Forum costs ...................................... 49

XXI. UN.GIFT Member States briengs (2007-2010) ............................ 51

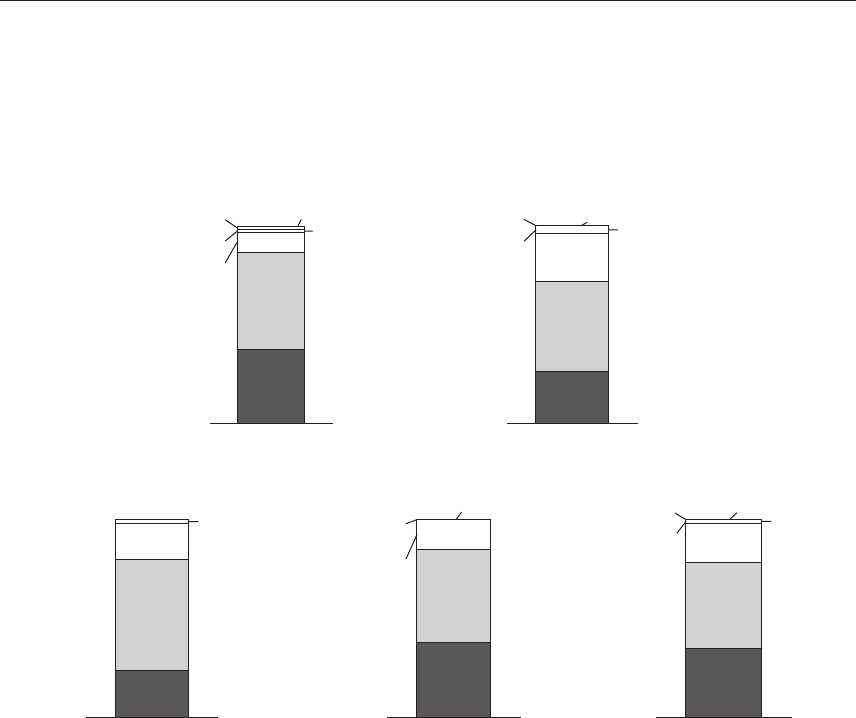

XXII. Demographic of SARC participants by type ................................ 58

XXIII. Demographic of SARC participants by nationality ........................... 58

XXIV. Overview of UN.GIFT South Asia budget and activities ...................... 59

XXV. Stakeholder feedback on SARC impact ................................... 60

v

Page

XXVI. Knowledge sharing and networking at SARC ............................... 61

XVII. Stakeholder perspectives on UN.GIFT continuation ......................... 71

Tables

1. Project budget and expenditures (2007-2011) ................................. 5

2. Project budget, expenditures and activities by output area ........................ 7

3. Evolution of UN.GIFT (2007-2010) ....................................... 10

4. Terms of reference evaluation criteria ....................................... 13

5. Methodology and stakeholder engagement ................................... 15

6. Comparison of UN.GIFT and ICAT objectives and activities/priorities ............. 18

7. List of UN.GIFT Regional Conferences ..................................... 25

8. UN.GIFT Expert Group Initiative tools and manuals ........................... 33

9. Joint Programme status as of December 2010 ................................. 34

10. List of partnerships secured and type of involvement ............................ 38

11. Funds raised for UN.GIFT’s budget ........................................ 40

12. In-kind donations and co-funding for UN.GIFT .............................. 41

13. UN.GIFT Small Grant Facility recipients .................................... 43

vi

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

AHT Anti-Human Tracking

AHTMSU Anti-Human Tracking and Migrant Smuggling Unit of UNODC

ECOSOC Economic and Social Council

ERP Enterprise Resource Planning

EGI Expert Group Initiative(s)

FRMS Financial Resources Management Service

ICAT Inter-Agency Coordination Group against Tracking in Persons

IEU Independent Evaluation Unit

ILO International Labour Organization

IOM International Organization for Migration

GA General Assembly

Global Report UNODC/UN.GIFT Global Report on Tracking in Persons

GPA United Nations Global Plan of Action to Combat Tracking

in Persons

JP Joint Programme

MS Member State(s)

NGO Non-Governmental Organization

OHCHR Oce of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

OSCE Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

PSA Public Service Announcement

PSC Programme/Project Support Costs

SARC UN.GIFT South Asia Regional Conference (Delhi 2007)

SAARC South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation

SGF Small Grants Facility

SC UN.GIFT Steering Committee

TIP Tracking in Persons

TOR Terms of Reference

UN.GIFT United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Tracking

UN.GIFT Secretariat UN.GIFT Project team (also referred to as the Project team or sta)

UN.GIFT Management Project Senior Manager and UNODC managers responsible for

UN.GIFT

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UNIAP United Nations Inter-Agency Project on Human Tracking

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

UNIFEM United Nations Development Fund for Women

UNODC United Nations Oce on Drugs and Crime

UNTOC United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime

Vienna Forum UN.GIFT Vienna Forum to Fight Human Tracking

(13-15 Feb. 2008)

vii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Tracking in persons (TIP) is one of the worst forms of human rights abuse, and one of the most

brutal forms of crime. It is a multi-dimensional phenomenon aecting both adults and children and

touching on nearly all countries of the world. Estimates of tracked persons are controversial and vary

widely depending on denition and methodology used, with over 800,000 people tracked across

borders annually (United States Department of State, 2007), over 2.4 million victims of labour traf-

cking (ILO 2005), and up to 27 million people in modern slavery across the world (Bales 1999),

with recognition of widespread under-reporting. Estimates on the prots from this illicit trade are at

US$32billion annually (ILO 2005).

In 2000, the General Assembly adopted e Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Tracking in

Persons, Especially Women and Children (“Tracking in Persons Protocol”), supplementing the

United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC). e Protocol laid the

foundation for global action on tracking in persons. However, while many organizations and Mem-

ber States developed anti-human tracking (AHT) programmes, a global spotlight on the issue and a

globally coordinated approach remained elusive, with a lack of consensus on a baseline of global traf-

cking patterns and varying views among Member States and other stakeholders about the specic

actions that should be taken to address the issue.

Recognizing these challenges, the Emirate of Abu Dhabi reached out to the United Nations Secretary-

General in 2006 proposing an international conference on anti-human tracking. In subsequent

discussions involving UNODC, as the custodian of the UNTOC and the Tracking in Persons Pro-

tocol, and a number of other stakeholders, the government of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi committed

US$ 15 million to launching a global conference and broader global initiative to ght tracking in

persons. e development of the project design was led by the Anti-Human Tracking and Migrant

Smuggling Unit (AHTMSU) of UNODC and UN.GIFT was launched in March 2007 as UNODC

Project GLOS83.

UN.GIFT was launched as a global initiative to foster awareness, global commitment and action to

counter human tracking, with an initial focus on ten regional conferences and one global confer-

ence. Additional output areas included increasing AHT related political commitment and capacity of

Member States, resource mobilization, and creating and strengthening support structures for victims

of human tracking. UNODC has managed UN.GIFT in cooperation with a Steering Committee

comprised of the International Labour Organization (ILO); the International Organization for Migra-

tion (IOM); the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); the Oce of the High Commissioner

for Human Rights (OHCHR); the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE);

and the donor government of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi.

By the end of 2010, total funds pledged by the initial donor and additional contributors amounted to

US$15.49 million and the Project had total expenditures of US$ 13.46 million,

1

including management

1

December 2010 expenditures are based on the FRMS interim report and cross-checked against UN.GIFT expenditure

tracking (showing minimal variance). As of 22 February 2011, nal corrections, including those resulting from currency

uctuations, are still pending.

viii

and programme support costs (PSC). All remaining pledged funds US$ 1.3 million of which were only

collected in 2011 have been allocated and will be disbursed in 2011. By February 2011, the remaining

UN.GIFT Secretariat activities were completed according to plan, with a number of ongoing activities to

be implemented by Small Grants Facility grantees and Joint Programme fund recipients.

is document is the report on the nal evaluation of the United Nations Global Initiative to Fight

Human Tracking (UN.GIFT), which was conducted by Dalberg Global Development Advisors, an

external evaluator, in collaboration with the Independent Evaluation Unit (IEU) of the United Nations

Oce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). It builds on the abridged preliminary evaluation, which was

submitted to the Fifth Session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention

against Transnational Organized Crime (18-22 October, 2010). e nal phase of the evaluation

focused on UN.GIFT activities, which were still ongoing in October 2010, most importantly the

Small Grants Facility, the Virtual Knowledge Hub and Joint Programmes. In addition, this nal report

incorporates feedback on preliminary results from various stakeholders, in particular from Member

States, UN.GIFT Steering Committee members, UNODC Management and the UN.GIFT Secre-

tariat. Findings and recommendations of this nal evaluation are based on the most recent data

available, including expenditures until December 2010 and 2011 allocations.

e evaluation was conducted in an independent, transparent, and participatory fashion, featuring an

in-depth desk review of Project documents and publications, six electronic surveys of several stake-

holder groups, and semi-structured interviews with 114 stakeholders, including Member States repre-

sentatives, UN.GIFT Steering Committee members, UN.GIFT and UNODC sta and management,

civil society organizations and, private sector partners. e methodological approach also included

two eld visits and in-country case studies of a regional conference in India and a Joint Programme in

Serbia. e results of this evaluation are thus based on a triangulation of a wide range of sources and

dierent data collection methods.

Based on evaluation ndings, the overall recommendation is to continue certain aspects of UN.GIFT

with renewed funding, a conclusion that is in line with the views of the majority of consulted stake-

holders. e key rationale for UN.GIFT’s continuation is that the Project continues to be the sole

inter-agency technical cooperation and coordination mechanism for AHT with institutional experi-

ence in piloting successful global AHT interventions. Despite some relevant but addressable short-

comings, a large number of activities have been successfully implemented and, critically, healthy

cooperation relationships have been built, particularly between UN.GIFT’s Steering Committee

member agencies, which represent many of the key players in the global ght against human track-

ing. In addition, the Project managed to establish a relatively strong brand with global AHT decision

makers and practitioners, though not necessarily on the regional or country levels.

is nal evaluation report notes that important progress has been made by UNODC, the UN.GIFT

Steering Committee and the UN.GIFT Secretariat on interim evaluation recommendations in the

months since the release of the preliminary evaluation report in October 2010. e evaluation team

commends UN.GIFT management for having already taken action on ideas triggered by this evalua-

tion. Most important, UN.GIFT management has engaged in extensive consultations with Member

States and other stakeholders, and a number of the key portfolio strategy and governance recommen-

dations are in the process of being incorporated into a new strategy, as part of the ongoing strategic

planning process for a potential new phase of UN.GIFT. Another important example of the imple-

mentation of evaluation recommendations regards the knowledge transfer from UN.GIFT’s Small

Grants Facility to the United Nations Voluntary Trust Fund for Victims of Human Tracking, called

for by the Global Plan of Action to Combat Tracking in Persons (GPA), which was adopted by the

General Assembly on 30 July 2010 and launched on 31 August, 2010.

e fact that some of the recommendations made in this evaluation report may already be in the pro-

cess of being adopted or implemented does not render this report obsolete but rather reinforces the

importance of its ndings and recommendations.

ix

ere is important context to consider when evaluating this initiative. UN.GIFT attempted to achieve

a very ambitious goal of creating a “global movement” to address the abhorrent crime of human traf-

cking. However, the approach for addressing this crime is quite complex, and requires coordination

across multiple agencies and disciplines. Furthermore, UN.GIFT’s multi-agency structure, involving

both United Nations agencies and non-United Nations global (IOM) and regional (OSCE) bodies, is

novel and unprecedented within the setting of UNODC. ere are only very few examples of global

inter-agency structures within the United Nations system (e.g. UNAIDS, UN-Water, UN-Energy)

and only one example of an AHT inter-agency structure at the regional level, the United Nations

Inter-Agency Project on Human Tracking (UNIAP) in the Mekong region. It is also generally

acknowledged—as demonstrated by reform eorts such as the “One UN” process—that achieving

consensus and implementing a coordinated and innovative agenda within the constraints of the United

Nations system are very challenging tasks. It often takes multiple years of evolution and learning

before an eective working relationship is achieved.

In light of this context, this evaluation nds that UN.GIFT has lled an important gap as a platform

for facilitating inter-agency cooperation in AHT eorts at the global level, within and outside the

United Nations system. e Project has made important contributions towards raising awareness

among global decision makers, the funding, production, and dissemination of knowledge and capacity-

building tools, and the broadening of the anti-human tracking coalition, including partnerships

with select private and civil society organizations. e Project’s contributions and relevance have been

recognized by multiple United Nations resolutions and its role was highlighted by the General

Assembly in the Global Plan of Action to Combat Tracking in Persons.

After an initially challenging period, the governance and management of UN.GIFT have substantially

improved. In response to strong interest of Member States, UN.GIFT management invested signi-

cant time and resources in increasing the level of consultation. e Project was also responsive to

Member State guidance by re-focusing its activities on capacity-building after 2008. ere is now

greater role clarity among Steering Committee members and their participation has evolved from a

largely advisory function at the inception of UN.GIFT to more equitable, coordinated joint develop-

ment and oversight of UN.GIFT’s strategic approach, resource allocation and activities. e experi-

ence of UN.GIFT has also pointed to important lessons learned about the investments—both in

terms of budget and sta time—that are required to develop an eective infrastructure for facilitating

coordination and ensuring that important follow-through activities occur.

However, given the magnitude of its objectives, UN.GIFT is still at a nascent stage of promoting

global awareness and coordinated AHT action. Progress to date on the objectives of strengthening

victim support structures and resource mobilization, despite some accomplishments and increasing

investment, has been relatively limited. A number of governance and management challenges continue

to be an issue and will need to be addressed. In connection with measuring long-term impact, many

of the Project’s objectives were dened too broadly and featured few baselines and metrics to establish

impact conclusively. ere is also little clear evidence for sustainability at this point, though improved

inter-agency cooperation at the Steering Committee level suggests potential for a more sustainable

eort in the future.

If UN.GIFT is to continue, substantial lessons should thus be incorporated into any subsequent Pro-

ject phase. e UN.GIFT Steering Committee, in close consultation with Member States and other

key stakeholders, should ensure that the recommendations of this evaluation are reected in any new

phase by re-aligning the portfolio of activities to build on UN.GIFT’s strengths and key areas of need

going forward. Additionally, the Steering Committee and UNODC Senior Management should con-

tinue to ensure that UN.GIFT’s governance structure and management approach is revised, with

improved ability to engage with Member States, increased Project autonomy from UNODC, broader

stakeholder participation, and more transparent and better dened results indicators, leading to greater

accountability.

x

e Summary Matrix in annex I provides an overview of the nal key evaluation ndings and recom-

mendations. Subsequent report sections and a detailed methodological appendix provide in-depth

information on UN.GIFT Project background, evaluation methodology, ndings, recommendations,

as well as lessons learned and best practices.

xi

MANAGEMENT RESPONSE

UNODC Senior Management agrees with the recommendation to continue and renew the UN.GIFT

Project, pending Member States’ consultation and donor funding, leveraging its core strengths in

order to meet the substantial ongoing need for inter-agency technical cooperation in the eld of anti-

human tracking.

Lessons learned

UNODC Senior Management agrees with the need to fully engage Member States in a consultative

process to dene the future phase of UN.GIFT and to work with Member States to identify eective

means of engagement.

UNODC is pleased to note the positive impact of the UNODC/UN.GIFT Global Report. e

Global Plan of Action has called for the production of a biennial UNODC report on “patterns and

ows of tracking in persons at the national, regional and international levels in a balance, reliable

and comprehensive manner, in close cooperation and collaboration with Member States”. To support

the development of the continuing, eective, consultative and transparent reporting process requested

by Member States, UNODC plans to establish a dedicated Global TIP programme of work, which

will incorporate lessons learned from the preparation of the UNODC/UN.GIFT Global Report as

well as of periodic global reports, such as the UNODC World Drug Report.

UNODC Senior Management has acted upon the recommendation to ensure that the results and the

lessons learned from the UN.GIFT Small Grants Facility are conveyed to the management of the

United Nations Voluntary Trust Fund for Victims of Human Tracking. At the Board of Trustees’

rst meeting, a detailed presentation of the UN.GIFT Small Grants Facility was held and all relevant

documents were shared with the Board members, who decided to base the Trust Fund’s Small Grants

Facility on the UN.GIFT pilot.

e lessons learned from the development and implementation of a series of Joint Programmes will

inform future joint anti-tracking activities at the country and regional level.

Draft Strategic Plan UN.GIFT 2011-2015

UNODC Senior Management agrees with the recommendation made in the preliminary and nal

report to develop a strategy that features both an agenda for global level inter-agency cooperation, and

region-specic agendas. Together with the SC members and in consultation with Member States, the

process of developing a draft strategy for a proposed next phase of UN.GIFT was started in November

2010. A series of recommendations put forward in the evaluation are addressed in the draft strategy

and will guide UN.GIFT’s future action.

xii

e draft strategy identies three main areas of work, which will complement and promote the activi-

ties of the individual SC organizations: Knowledge Management, Strategic Support and Interventions

and Promoting Global. e knowledge management activities include the continuation and expan-

sion of the Virtual Knowledge Hub and the collection and dissemination of lessons learned. is

component also includes the systematic documentation of outcome level results data, base-line studies

and investments in developing feedback from end-beneciaries and partners as suggested in the nal

evaluation report.

e strategic support and interventions cater to the recommendation to strengthen the regional

dimension of UN.GIFT’s work by ensuring that global inter-agency anti-human tracking activities

and outputs are designed to be leveraged regionally and locally. ey further embrace the recommen-

dation to direct more technical assistance toward strengthening victim support structures as an integral

component of global, regional and national capacity-building activities and to increase the level of

interagency cooperation at the regional and country level. e component will also draw on the

lessons learned from UN.GIFT’s ongoing Joint Programmes.

e component of promoting global dialogue captures the recommendations to make inter-agency

cooperation an explicit objective and to develop a detailed pro-active stakeholder communication plan

for the next phase. It also draws on the recommendation to utilize lower cost events at the local level

with more clearly dened deliverables.

Governance and management

UNODC Senior Management agrees to continue to host UN.GIFT and to support the autonomy of

the UN.GIFT Secretariat in line with UN.GIFT’s role as a multi-agency platform. UNODC Senior

Management will ensure further clarication of roles and responsibilities of UN.GIFT vis-à-vis other

UNODC anti-human tracking eorts and will present a coherent and integrated response to human

tracking within its ematic Programme on Transnational Organized Crime.

Regarding the composition of the UN.GIFT SC, discussions have already taken place within the SC

on the potential to broaden participation and increase external stakeholder involvement. A careful

review of interested organizations and their operational capacities should take place to ensure an ade-

quate balance in broader participation, while maintaining an ecient and operational decision- making

structure. UNODC will also continue to increase the equity of participation in UN.GIFT through

clear decision-making rules and potentially, a rotating Steering Committee chair.

UNODC Senior Management agrees that the next phase of UN.GIFT should focus on multi-year

projects and allow for joint fundraising by SC members. is should include striving for a more diver-

sied donor base, while maintaining and sustaining the high quality partnerships already established

by UN.GIFT.

e component of promoting global dialogue captures the recommendations to make inter-agency

cooperation an explicit objective and to develop a detailed pro-active stakeholder communication plan

for the next phase. It also draws on the recommendation to utilize lower cost events at the local level

with more clearly dened deliverables.

xiii

STEERING COMMITTEE RESPONSE

Recommendations on relevance

Pending Member States’ consultation and donor funding, the UN.GIFT Steering Committee (SC)

2

agrees with the recommendation to develop further and jointly implement the UN.GIFT Project. It

will do so by leveraging its core strengths in order to meet the substantial ongoing need for inter-

agency technical cooperation in the eld of anti-human tracking while taking into account and capi-

talizing on the respective mandates of each of the member organizations, their expertise, accumulated

experience and developed partnerships and networks.

e SC accepts that UN.GIFT should maintain its role in networking and providing technical inter-

agency cooperation at the global level, while at the same time increasing the level of multi-agency

activity at the regional and country level where such inter-agency coordination eorts do not exist

today.

3

e UN.GIFT SC agrees with the need to clarify UN.GIFT’s role vis-à-vis the Inter-Agency Coordi-

nation Group against Tracking in Persons (ICAT) and will take steps to identify opportunities for

synergy between the two.

Recommendations on effectiveness

e UN.GIFT SC agrees to continue to review the progress of ongoing eorts such as the Joint

Programmes.

e UN.GIFT SC is pleased to inform that a strategy is currently being developed featuring an agenda

for global level inter-agency cooperation and opportunities for region-specic agendas tailored to spe-

cic needs where relevant local coordination platforms do not exist today. UN.GIFT will focus its

activities where it has demonstrated success to date and where it is well-positioned to do so with

improved execution, including the prioritization of activities with measurable impact and with a clear

need for cross-disciplinary, inter-agency eorts. It will develop joint activities at the global level, capi-

talizing on the mandates and expertise of the various member organizations involved and aimed at

nding ground breaking solutions.

e global agenda could feature:

(a) Providing an ongoing forum for inter-agency technical cooperation of agencies active in

human tracking;

(b) Producing and disseminating multi-agency anti-human tracking knowledge products,

including serving as a multi-stakeholder anti-human tracking knowledge hub;

2

Comprised of ILO; IOM; OHCHR; OSCE; UNICEF and UNODC.

3

Such inter-agency coordination does exist in Brussels where joint work has been undertaken on the EU directives.

xiv

(c) Documenting and sharing globally good practices and lessons learnt in ghting human

tracking;

(d) Facilitating engagement with civil society, worker’s organizations and private sector on anti-

human tracking issues;

(e) Involving survivors of tracking in persons when developing anti-tracking activities;

(f) Developing, rening and disseminating multi-disciplinary inter-agency capacity-building

tools and training programmes;

(g) Developing innovative sectoral and thematic responses and ways of working that are cutting

edge and which hold promise in reducing human tracking;

(h) Supporting awareness-raising campaigns, with emphasis on more targeted and measurable

inter-agency advocacy eorts;

(i) Fundraising for inter-agency coordination and technical cooperation projects, including the

mobilization of resources for victim support and prevention structures.

e UN.GIFT SC also agrees that inter-agency technical assistance geared toward strengthening vic-

tim support structures should be an integral component of global capacity-building activities and

regional and national activities via Joint Programmes.

e SC acknowledges that fundraising for inter-agency coordination and technical cooperation pro-

jects should be an integral component of the Project’s next phase. Subject to the specic regulatory

restrictions within each respective organization, SC members should have equal and shared fund-

raising responsibilities for UN.GIFT.

e UN.GIFT Secretariat will track and report on future in-kind contributions in a consistent manner

so as to ensure that all contributions are fully captured.

e SC agrees that a clear logical framework with distinct and well dened activities should be

established for the next phase of the project, including a comprehensive needs assessment to be

embedded in its future strategy. UN.GIFT’s future strategy should include detailed and measura-

ble impact as well as operational performance indicators. In addition, resources should be allocated

into base-lining studies to ensure that all inter-agency activities can be better managed and

evaluated.

Recommendations on efficiency

e SC agrees with the recommendation to prioritize inter-agency activities that can be leveraged at

local levels and utilizing lower cost events with more clearly dened deliverables.

e UN.GIFT Secretariat has invested in output-budget recording for UN.GIFT activities and com-

pilation of lessons learned logs. e SC agrees that UN.GIFT would benet from activity-level budget

and process tracking and investments in collecting and documenting feedback from end- beneciaries

and partners. ese should form part of the strategy development exercise and costing of the next

phase.

In order to further improve eciency among partner organizations, the SC will build on existing tem-

plates and lessons learned to establish standard agreements for Joint Programmes in the framework of

UN.GIFT.

xv

Recommendations on impact

UN.GIFT SC agrees that the strategy for subsequent phases of UN.GIFT should feature more realistic

objectives tied to time-delimited and measurable metrics as well as guiding principles to inform activ-

ity prioritization, such as by focusing on activities that cannot be implemented by any single agency

independently.

Another aspect of prioritization will be to strengthen the regional dimension of UN.GIFT’s work, to

ensure that global inter-agency activities and outputs are designed to be leveraged regionally and

locally.

Recommendations on sustainability

UN.GIFT SC agrees that a new strategy should focus on multi-year projects and allow for joint

fundraising by SC members. is should include striving for a more diversied donor base, while

maintaining and sustaining the high quality partnerships already established by UN.GIFT.

Recommendations on partnerships, management and governance

UN.GIFT SC agrees that a new strategy should focus on multi-year projects and allow for joint

fundraising by SC members. is should include striving for a more diversied donor base, while

maintaining and sustaining the high quality partnerships already established by UN.GIFT.

In order to improve the governance of UN.GIFT, clearer branding and communication on UN.GIFT’s

role should be sought and communicated by all SC members. In a next phase of UN.GIFT, a clear

communication plan with a focus on Member States and other relevant stakeholders should be devel-

oped. To this eect, the UN.GIFT HUB containing up to date online information on anti-human

tracking activities of UN.GIFT and its partners provides a solid basis for improved communication,

information gathering, knowledge generation and sharing of relevant information on anti-human

tracking initiatives worldwide.

e UN.GIFT SC acknowledges that there were serious and sustained tensions within the SC for

some parts of the rst phase of the initiative. Important lessons were learnt from the process of estab-

lishing an inter-agency initiative and it is worth highlighting the good will and mutual understanding

among SC members in this current stage.

Regarding the composition of the UN.GIFT SC, discussions have already taken place within the SC

on the potential to broaden participation and increase external stakeholder involvement by creating an

associate member track. A careful review of interested organizations as potential associate members is

taking place so as to ensure an adequate balance in broader participation, while maintaining an ecient

and operational decision-making structure.

e UN.GIFT SC agrees that UNODC should continue to host UN.GIFT for the next phase, while

ensuring accountability to Member States through:

(a) Engagement of Member States in a consultative process to dene the future phase of

UN.GIFT and to identify eective means of engagement on an ongoing basis;

(b) Agreement at the SC on prioritization of activities and work plans, while retaining UNODC’s

reporting role to its Member States on behalf of the SC and duciary nancial responsibility, transpar-

ency and administrative relationship;

xvi

(c) Increased emphasis on leveraging existing expertise and capabilities from SC members;

(d) Continuing to increase the equity of participation in UN.GIFT through clear decision-

making by consensus and in line with the mandates of the SC members and rotating Chairs for the

Steering Committee meetings;

(e) Clear division of tasks preferably where all those who are being coordinated have responsi-

bilities for at least one element of delivery.

1

I. INTRODUCTION

Background

UN.GIFT project background

United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Tracking (UN.GIFT) is a multi-stakeholder part-

nership against human tracking launched in March 2007 and managed by the United Nations

Oce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in collaboration with a Steering Committee. Members of the

Steering Committee are the International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Organization

for Migration (IOM), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the United

Nation’s Children Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Oce of the High Commissioner for Human

Rights (OHCHR), UNODC and a representative of the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi. A small

UN.GIFT Secretariat, hosted by UNODC, provides support to the Steering Committee and drives

the implementation and coordination of Programme activities.

In accordance with the initial project document, the overall objective of UN.GIFT is to prevent traf-

cking in persons and reduce the number of tracked persons worldwide. e immediate objectives

are to (a) foster awareness, global commitment and action to counter human tracking in partnership

with dierent stakeholders including Governments, the international community, non-governmental

organizations and other elements of civil society and media, and (b) to create and strengthen support

structures for victims of human tracking.

Aside from these explicit objectives, the original project document and progress reports refer to implicit

goals of “setting in motion a broad-based global movement that will attract the political will and

resources needed to stop tracking in persons” and producing a “turning point in the ght against

tracking in persons.” is was to be accomplished by “fostering cooperation and coordination by

creating synergies among ongoing endeavours led by United Nations agencies, international organiza-

tions and other stakeholders, taking into account their respective areas of expertise, accumulated

knowledge and experience, as well as existing networks”.

In line with these objectives, UN.GIFT has been managed against ve output areas since 2007

(gureI):

(a) Output 1: Increase awareness and knowledge on human tracking;

(b) Output 2: Increase political commitment and capacity of Member States to counter human

tracking and implement the Tracking Protocol;

(c) Output 3: Mobilize resources to implement the action required to combat tracking at the

international, regional and national level;

(d) Output 4: Organize a Global Conference to assess the global tracking situation and to

promote global action against human tracking.

2

IN-Depth evaluatIoN: uN.GIFt

Project documents additionally refer to four Project pillars cutting across these output areas. Consid-

ering the multiple objectives of many UN.GIFT initiatives, complex overlaps between “pillars” and

“outputs”, and several revisions to Programme activities over the past three years, there is signicant

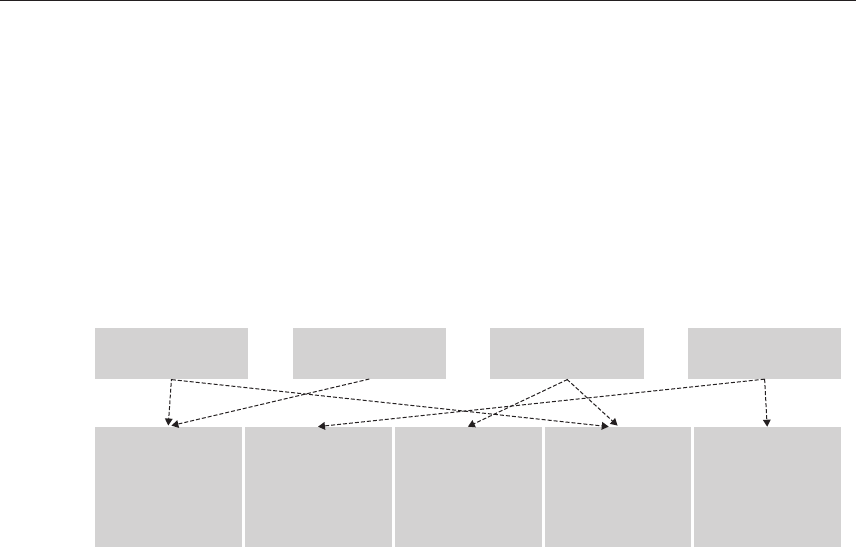

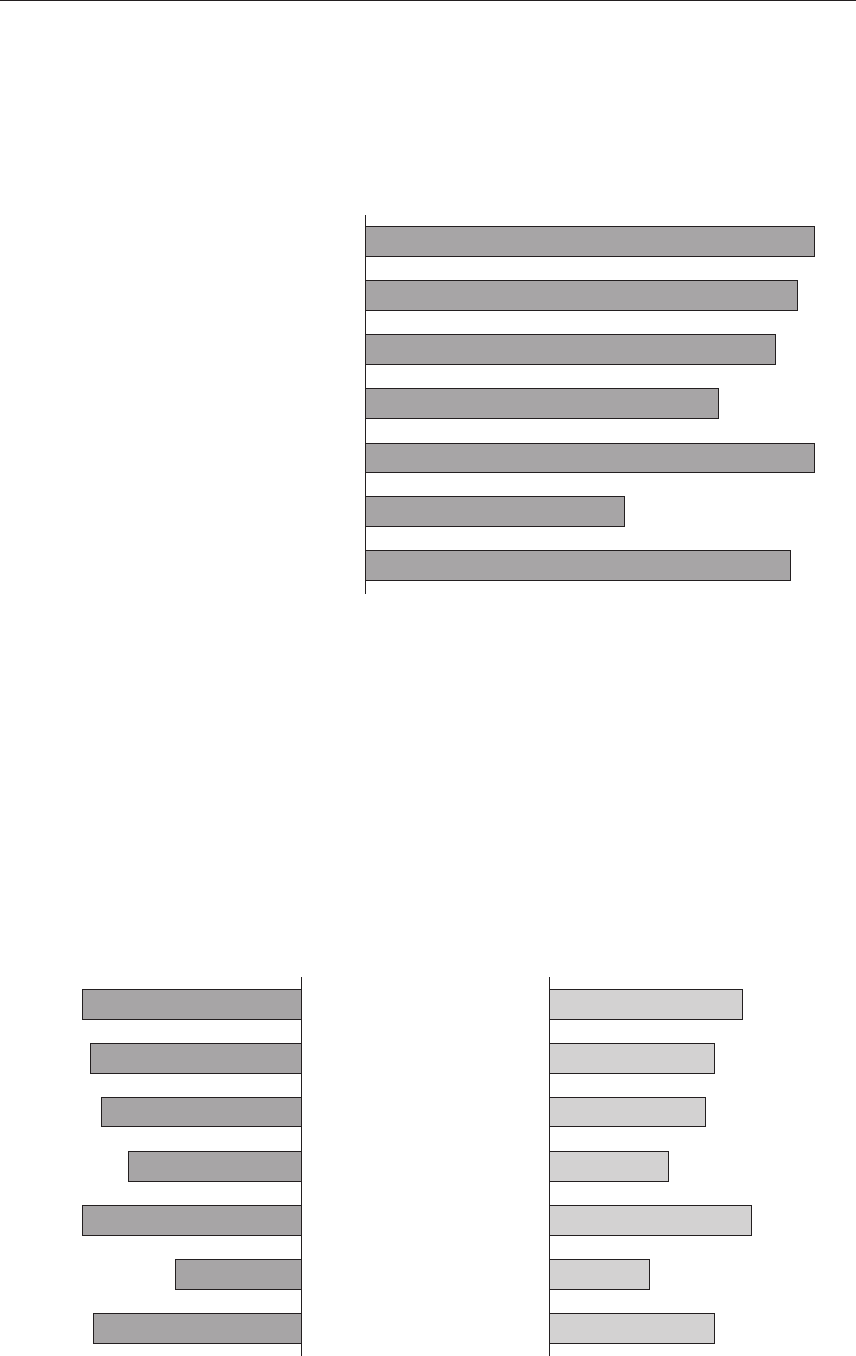

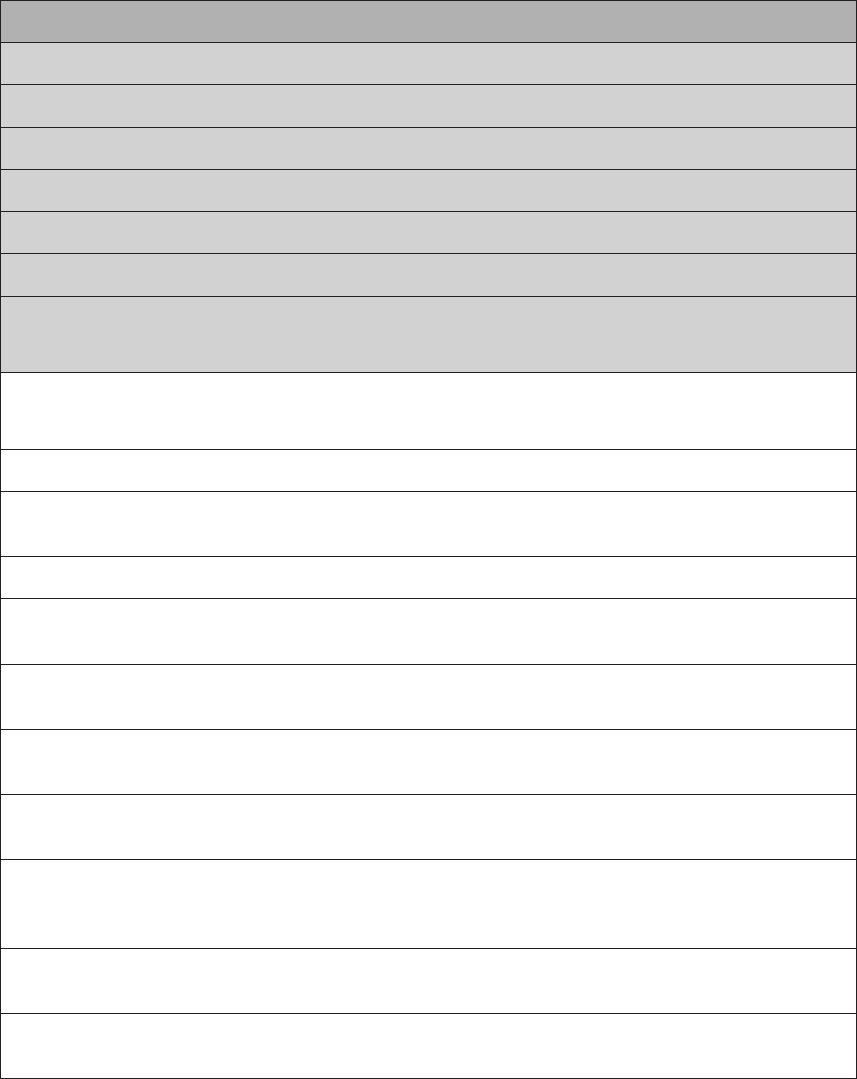

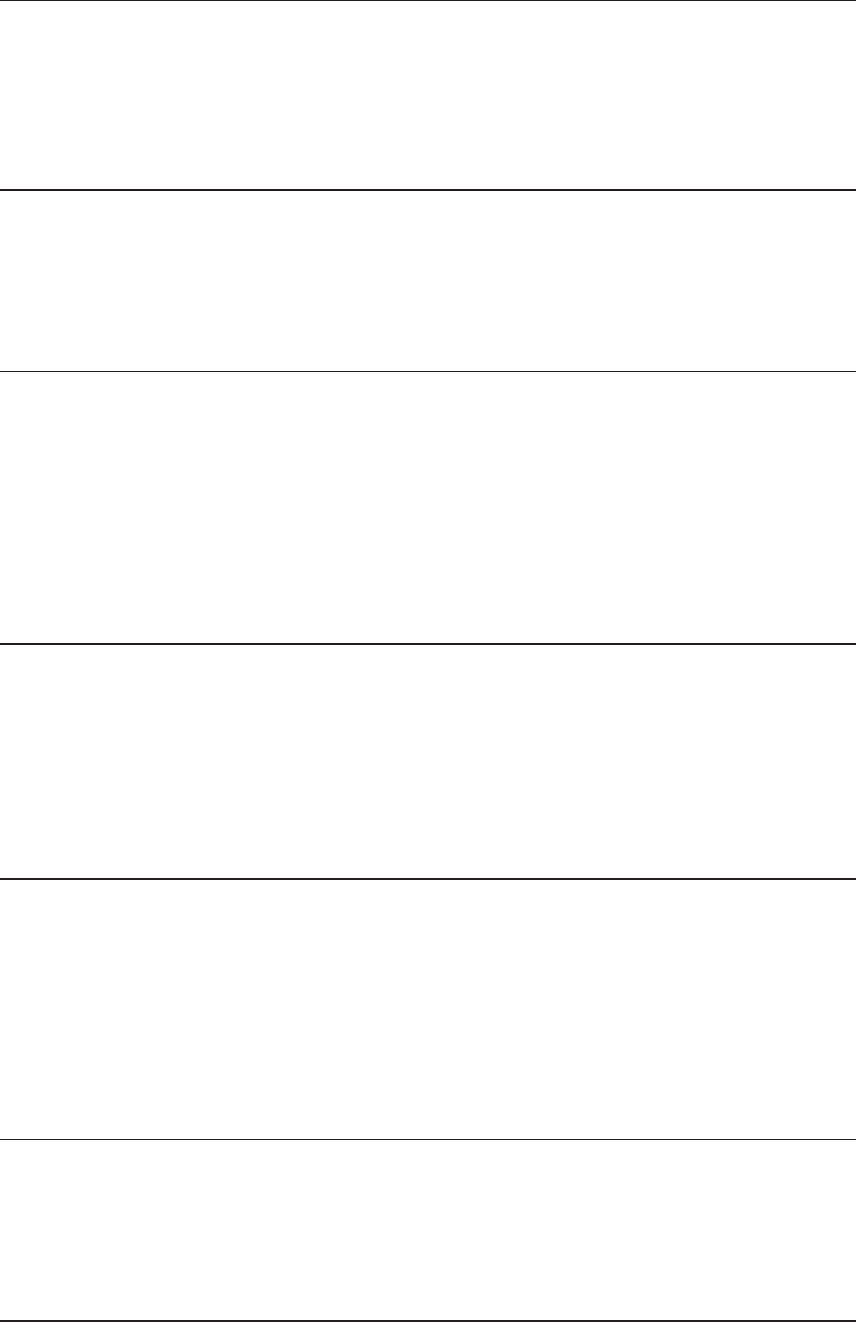

complexity in the initial logical framework (gure 1):

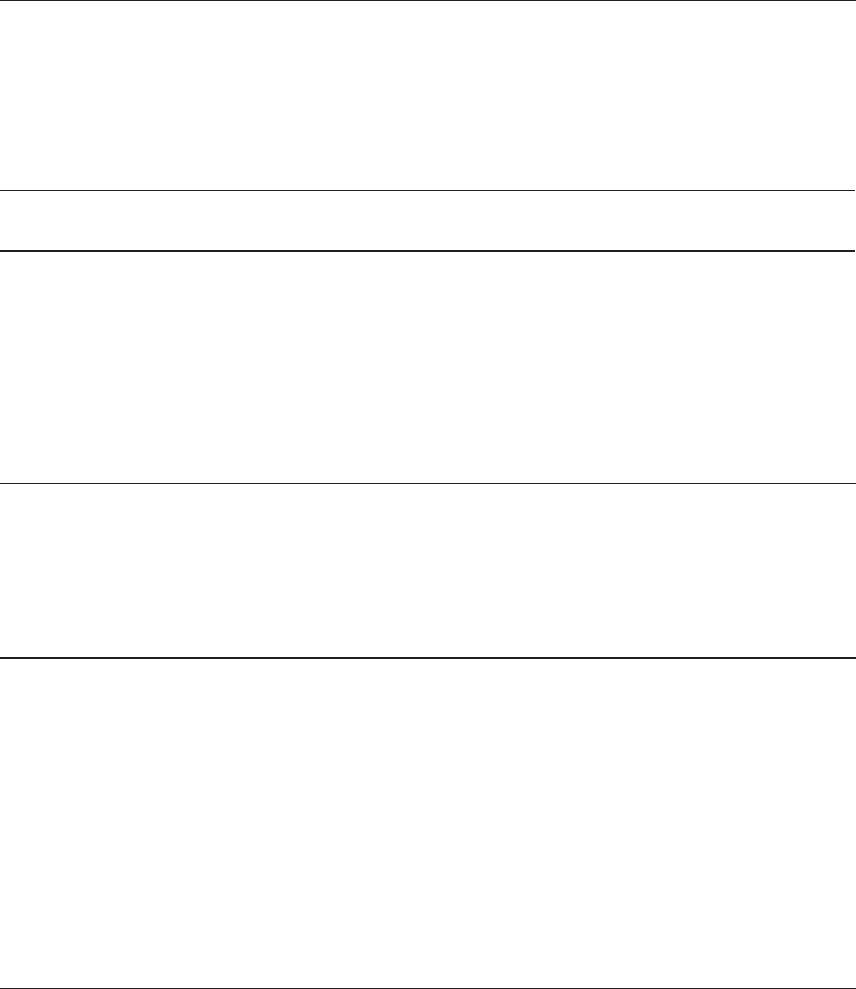

Figure I. UN.GIFT Logical Framework with pillars, outputs and key activities

Background on management and governance

e United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Tracking (UN.GIFT) is managed by the

United Nations Oce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) as a global technical assistance Project

(GLOS83), nanced primarily through a Funding Agreement between UNODC and the Govern-

ment of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi.

e UNODC, guardian of the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) and

the “Tracking Protocol”, has acted as the Executing Agency and host of UN.GIFT’s Secretariat from

the Project’s inception. UNODC has implemented the Project under its Division for Operations

(DO) and, with internal re-alignment in mid-2010, under its Division for Treaty Aairs (DTA).

roughout the project period, UNODC has provided all necessary administrative and operational

support, including IT, nance, and logistics.

Pillars

Output

areas

Key

activities

2007-2008

Key

activities

2009-2010

4. Organize a global

conference to assess

the global trafficking

situation and to

promote global action

against human

trafficking

3. Mobilize resources

to implement the

action required to

combat trafficking at

the international,

regional and national

level

2. Increase political

commitment and

capacity of MS to

counter human

trafficking and

implement the

Tr afficking Protocol

1. Increased

awareness and

knowledge of

human trafficking

• Public awareness

campaigns (TV series,

films, publications,

PSAs)

• UN Global TIP Report

and small topical

reports

• 10 regional conferences

• Expert Group Initiatives

(e.g. manuals, tools)

• Parlamentarian

handbook and events

• Inter-agency

coordination at SC level

• Capacity-building

training events

• Women Leaders’

Council

• Fundraising activities

• Public-private

partnership activities

• Vienna Forum and

affiliated promotional

events (e.g. Film Forum,

Journey Against Sex

Tr afficking installation)

and publications

• Engagement and

funding for select global

NGOs (e.g. Stop the

Tr afik)

• Study exchanges and

training sessions with

service providers

• Public awareness

campaigns targeting

public at large, youth

and private sector

• Virtual Knowledge

Hub

• Methodology for UN

multi-agency report

on TIP

• 6 Joint Programmes

1. Activities under output area 3 mostly focuses on the private sector.

2. Joint Programmes typically have a victim support component but are listed under output area 2.

• Increased private

sector engagement

through awareness,

Business Leaders’

Award and PPP pilot

projects at global and

national/regional levels

• N/A • Victim Tr anslation

Assistance Tool (MP3

audio tool)

• Small Grants Facility

(US$ 529,000)

5. Increase support

to victims of

trafficking through

NGOs and other

service providers

1. Advocacy efforts to

raise awareness

2. Knowledge

creation to impact policy

3. Coordination

between intl. orgs.

4. Capacity-building of

stakeholders

3

IntroductIon

UN.GIFT has been governed by UNODC in partnership with a Steering Committee (SC), consisting

of four United Nations agencies (UNODC, ILO, UNICEF, and OHCHR), one international organi-

zation, IOM and one regional organization, OSCE, as well as the donor government of Abu Dhabi.

Over the course of the initiative, the role of the SC has evolved steadily from a more advisory function

into a more participatory joint oversight mechanism (also see Management and Governance ndings).

Currently, the role of the Steering Committee is to provide advice on the substantive implementation

of the Project and to act as its coordinating body.

Steering Committee decisions are made by consensus. e Steering Committee has been chaired by

the UN.GIFT Manager and meets regularly as deemed necessary by the committee chair, with

21meetings to date since Project inception in March 2007.

As of late 2010, agreed responsibilities of Steering Committee members are as follows:

(a) Promote UN.GIFT and advocate towards its goals;

(b) Support the development of joint activities, particularly of the UN.GIFT joint Projects;

(c) Fundraise for the joint Projects and other UN.GIFT activities;

(d) Represent UN.GIFT within their agencies and in other fora as appropriate;

(e) Coordinate human tracking interventions among its members and their respective

networks and alliances;

(f) Create synergies and avoid duplication to ensure the most cost eective delivery of activities

and actions to counter human tracking; and

(g) Contribute to UN.GIFT’s knowledge network.

A relatively small UN.GIFT Secretariat has led the day-to-day management of the Project and has been

responsible for supporting the UN.GIFT Steering Committee. e functions of the Secretariat have

varied for dierent activities and products, ranging from funding, management and coordination to the

development of specic events, knowledge products, and capacity-building tools.

From September 2007 to July 2010, the Secretariat has been led by a Senior Manager (D-1), respon-

sible for chairing Steering Committee Meetings, corporate partnership eorts and constituency-

building, and achievement of Project objectives.

Aside from the Senior Manager, the size of the Secretariat’s core sta, including one General Service

position, has ranged from 5 (2009) to 8 (2007-2008) sta members and long-term consultants.

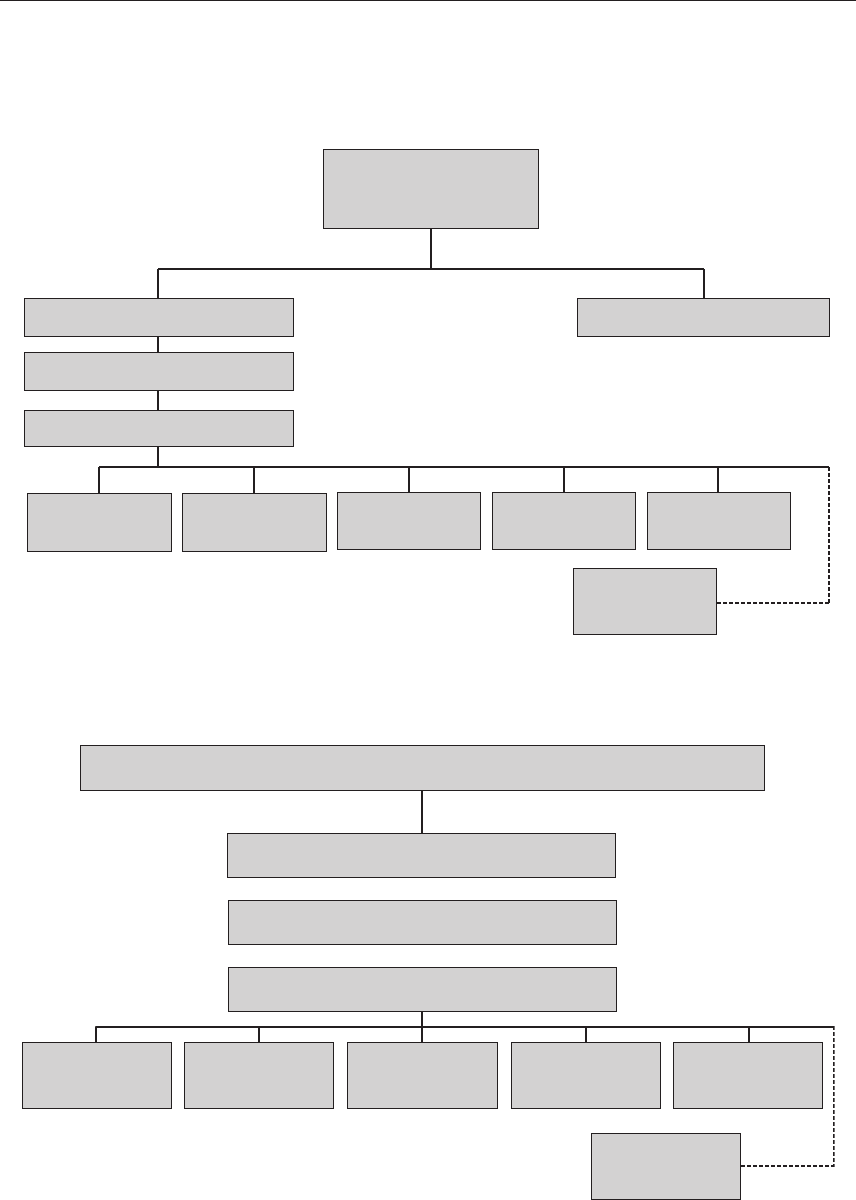

As of June 2010 the Secretariat consisted of eight personnel, including one senior manager (D-1) two

full-time professional sta (one P-3, one temporary P-3), one part time professional sta (P-3,

20 per cent), a general service sta (G-5), and three consultants whose contract terms expire by

December31, 2010 and will be renewed till March 31, 2011 to ensure Project completion and/or

transition to a new phase (gures II and III).

4

IN-Depth evaluatIoN: uN.GIFt

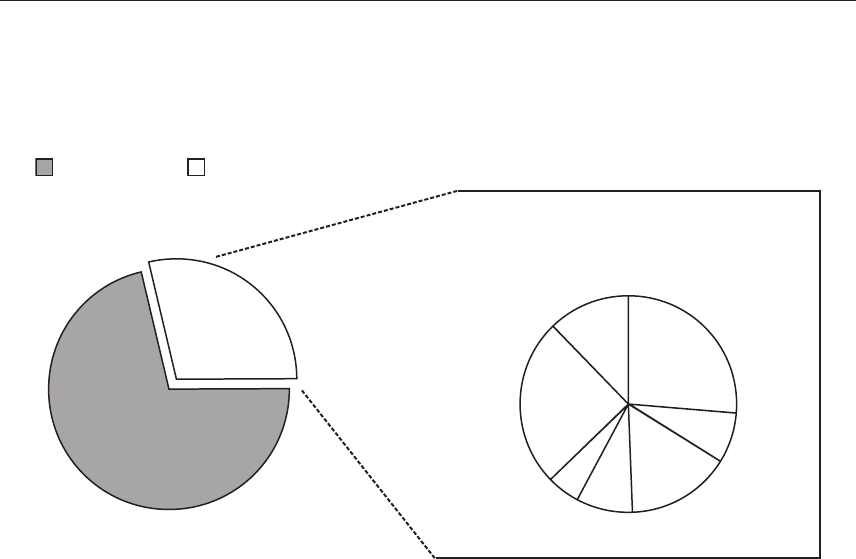

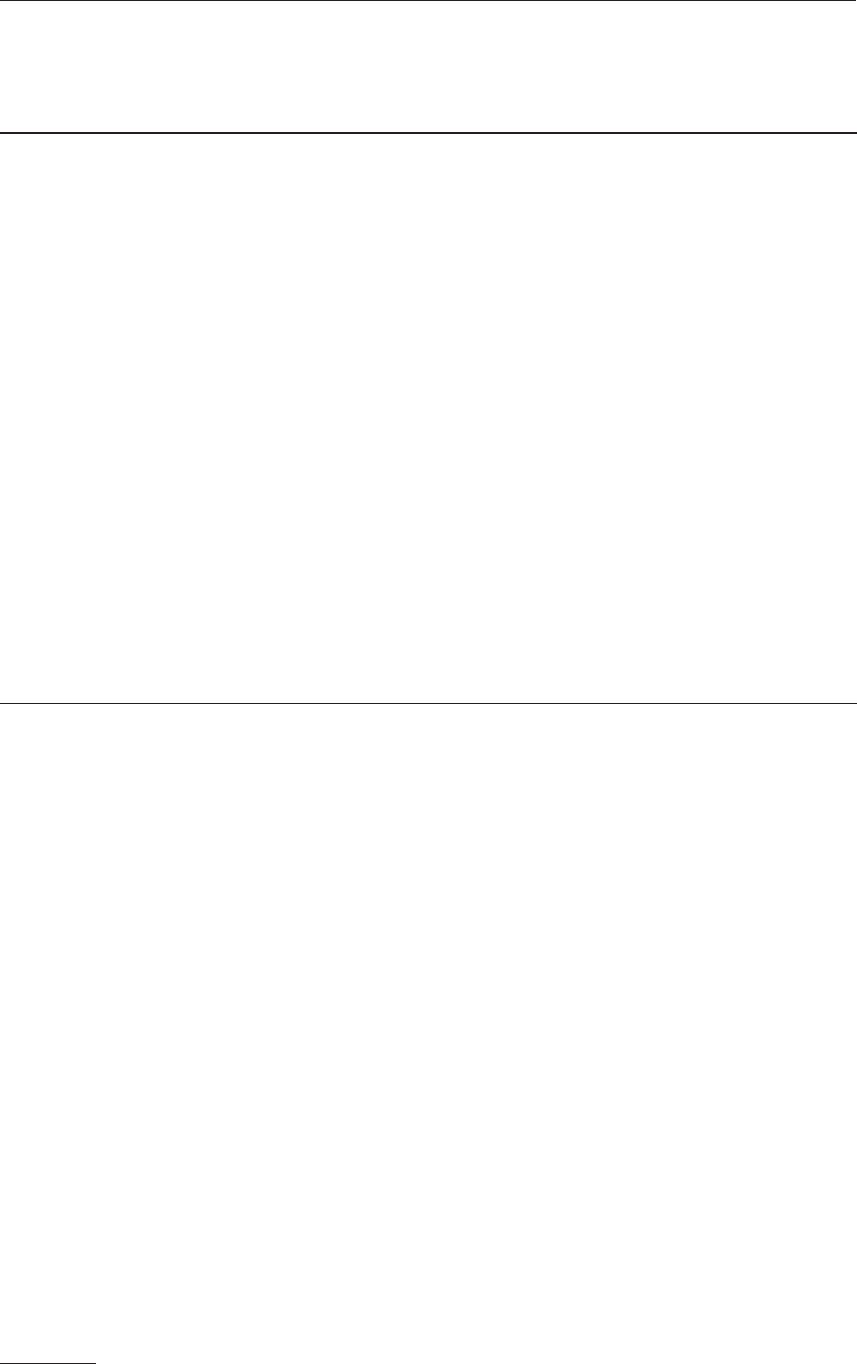

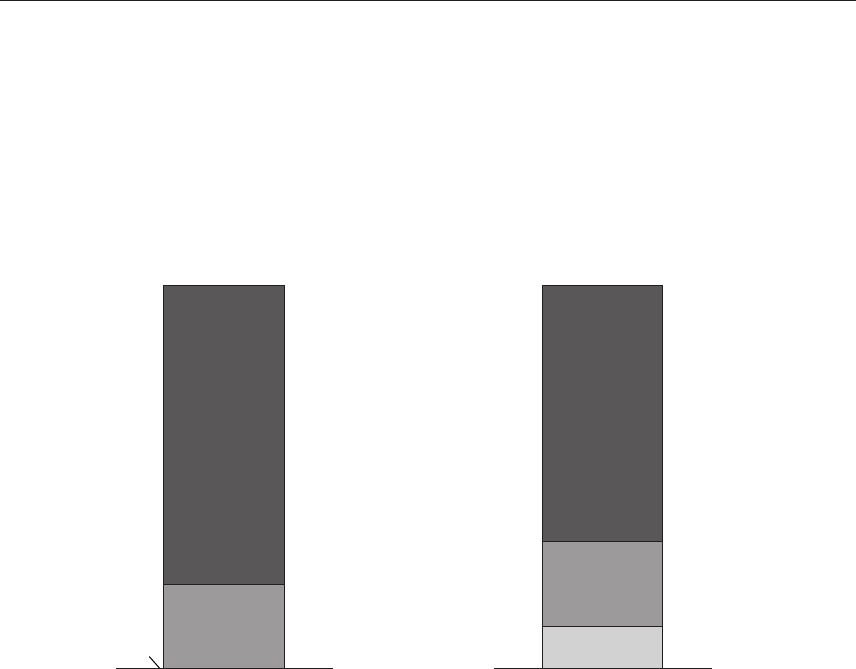

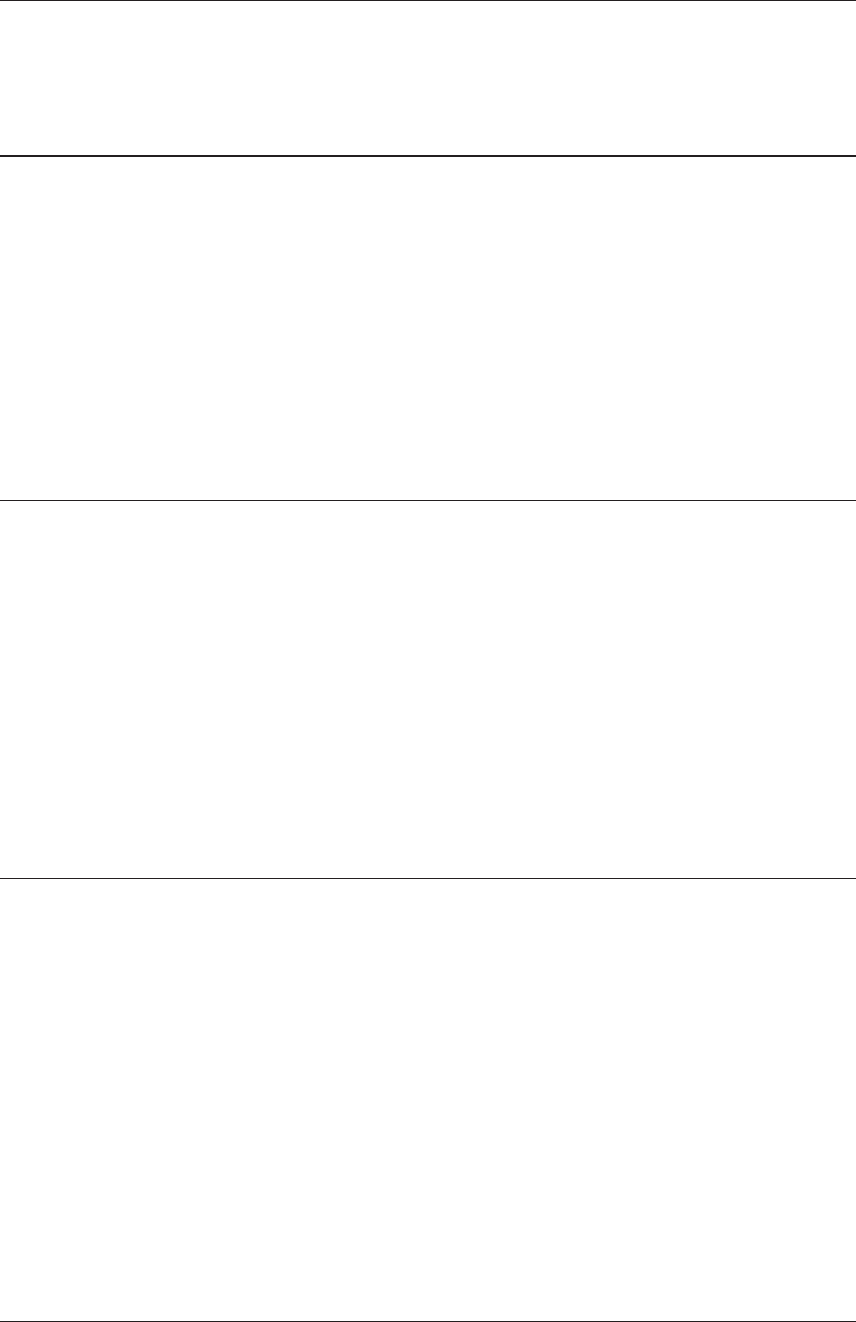

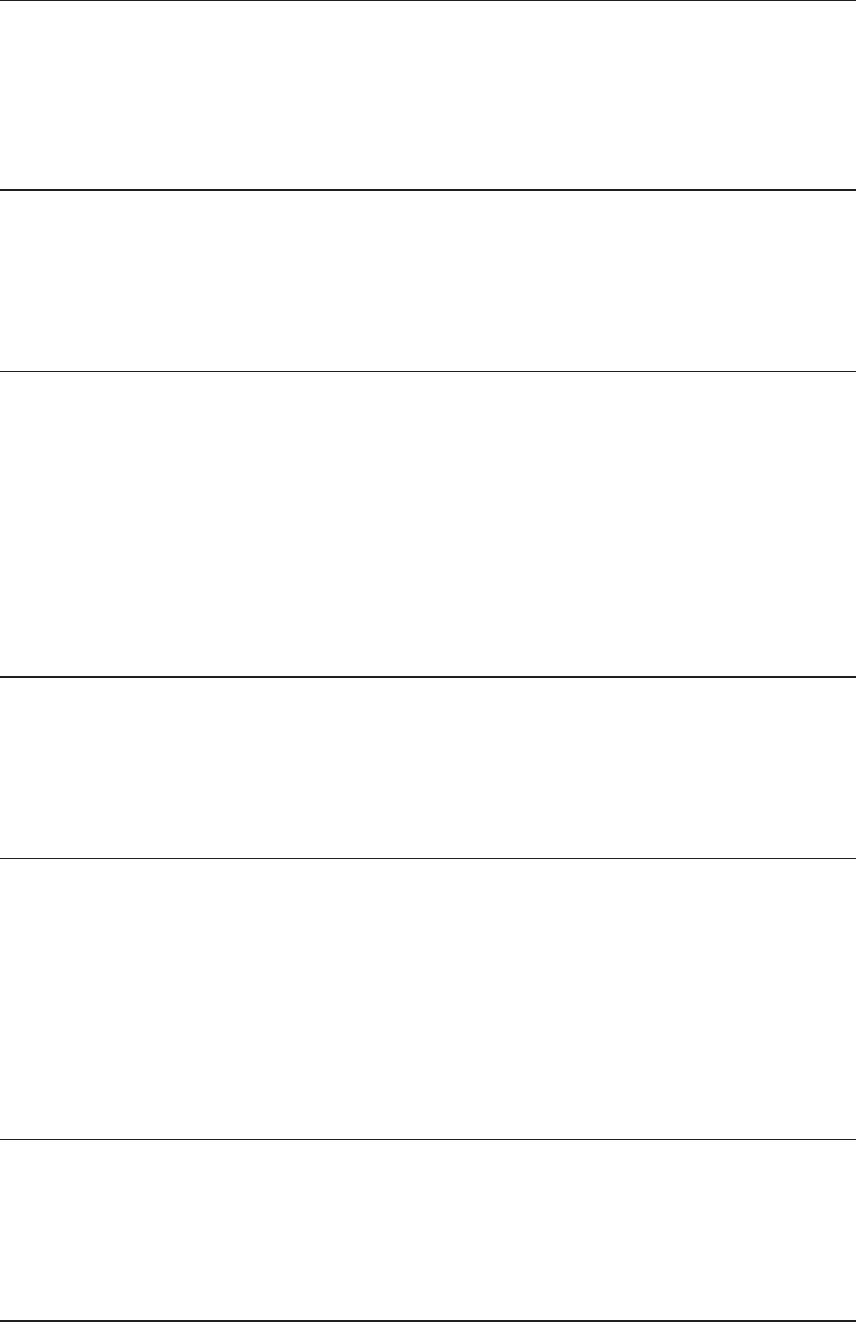

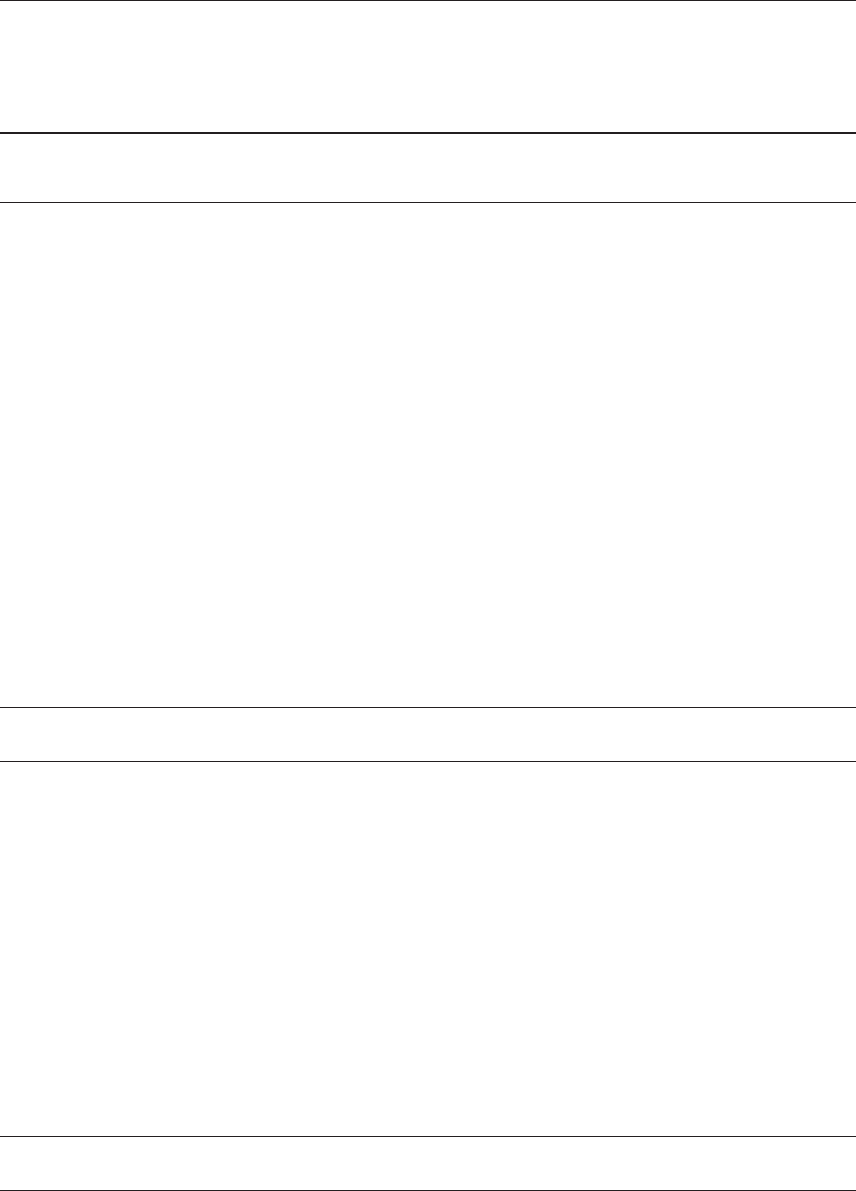

Figure II. UN.GIFT’s organizational structure (June 2010)

Figure III. UN.GIFT’s organizational structure (December 2010)

Programme Officer/OIC (P-3)

AHTMSU

Public Information

Officer (P-3)

Private Sector

Focal Point

(Consultant)

Joint Programmes

Coordinator

(Consultant)

Civil Society

Focal Point

(Consultant)

Programme

Assistant (G-5)

Exec. Officer, Office

of the Executive

Director (28%) (P-3)

P-4 (Vacant)

UN.GIFT

Senior Manager (UN.GIFT and

Anti-Human Trafficking and

Migrant Smuggling Unit) (D-1),

stationed at UNICRI

Public Information

Officer (P-3)

Private Sector

Focal Point

(Consultant)

Joint Programmes

Coordinator

(Consultant)

Civil Society

Focal Point

(Consultant)

Programme

Assistant (G-5)

Exec. Officer, Office

of the Executive

Director (28%) (P-3)

Programme Officer (Strategy and Partnerships) (P-3)

Programme Officer (P-4)

UN.GIFT

Senior Manager (P-5)

During the various phases of the Project, UN.GIFT has funded additional personnel in the eld and

within various sections at UNODC headquarters in Vienna. e number of personnel within UNODC,

involved in supporting UN.GIFT, varied over time (0 to 4) and included sta embedded in the Anti-

Human Tracking and Migrant Smuggling Unit (AHTMSU), the Division of Policy Analysis (DPA),

Co-nancing and Partnerships Section (CPS), Policy Analysis and Research Branch (PARB), and Advo-

cacy Section (AS); the Procurement Section (PS); and UNODC Oce of the Director-General and

5

IntroductIon

Executive Director. In addition, consultants were temporarily funded by the Secretariat for specic activ-

ities like the Vienna Forum (12 consultants), research for the Global Report on TIP (9 researchers world-

wide) and Joint Programmes (1 per programme launched and co-funded positions).

Since mid-2010, the UN.GIFT Secretariat has worked under the UNODC Division for Treaty Aairs

(DTA) and—over the entire project period—UN.GIFT has worked closely with the Division for

Management (DM) for all aspects of Project implementation and with the Division for Operations

(DO) in relation to regional and country programmes. UN.GIFT’s senior manager is also ocer-in-

charge of the Integrated Programme and Oversight Branch of DO.

UN.GIFT financials

Overall Project expenditure through the end of 2010 has been US$ 13.46 million, out of a total pro-

ject budget of US$ 15.49 million.

4

e nal tranche of US$ 1.3 million was collected in early 2011.

e total budget includes original UAE funding as well as additional funds mobilized by the Project

over the years (see section 4.2.8 Mobilization of Resources). Table 1 below shows the distribution of

funds by output area and total overheads (general and administrative costs), which include project

management costs, organizational overheads in the form of Programme Support Costs (PSC), and

expenditures related to the evaluation.

4

is number includes organizational overheads in the form of programme support costs (PSC), as well as project

management costs and evaluation related expenditures. December 2010 expenditures are based on the FRMS interim report

and cross-checked against UN.GIFT expenditure tracking (showing minimal US$ 2.8k variance). As of 22 February 2011,

nal corrections, including those resulting from currency uctuations, are still pending.

Table 1. Project budget and expenditures (2007-2010)

March 2007-Dec. 2010

expenditures

Total UN.GIFT

budget

2007 2008 2009 2010

(till Dec.)

US$

millions

% of

spending

Remaining funds

(2011 forecast)

US$

millions

% of

budget

Output 1 1.26 1.42 0.15 0.31 3.15 23 0.22 3.37 22

Output 2 1.43 0.96 0.56 0.86 3.81 28 1.29 5.10 33

Output 3 0.27 0.06 0.02 0.16 0.52 4 0.12 0.64 4

Output 4 0.36 1.92 0.02 – 2.30 17 – 2.30 15

Output 5 0.04 0.01 0.05 0.65 0.75 6 0.16 0.91 6

Mgmt. costs 0.21 0.55 0.90 0.40 2.07 15 0.08 2.15 14

PSC 0.18 0.25 0.09 0.13 0.65 5 0.09 0.74 5

Evaluation – – – 0.20 0.20 2 0.08 0.28 2

Total 3.76 5.19 1.80 2.72 13.46 100 2.03 15.49 100

Output 1: Increase awareness and knowledge of human trafficking

Output 2: Increase political commitment and capacity of Member States to counter human trafficking and implement the Traffick-

ing Protocol

Output 3: Mobilize resources to implement the action required to combat trafficking at the international, regional and national

level

Output 4: Organize a Global Conference to assess the global trafficking situation and to promote global action against human

trafficking

Output 5: Increase support to victims of trafficking through NGOs and other service providers

Note: December expenditures are based on FRMS interim report and UN.GIFT expenditure tracking. As of 8 February 2011, final

corrections, including those resulting from currency fluctuations, are still pending. Management expenditures include the strategy

development process in December 2010; numbers may not add up to 100 per cent due to rounding.

Source: UN.GIFT Secretariat; Dalberg analysis.

6

IN-Depth evaluatIoN: uN.GIFt

As of January 2011, a total of approximately US$ 2 million had not yet been disbursed but allo-

cated to the dierent output areas, with the majority (US$ 1.29 million) being allocated to output

area2 (table 1). In addition, remaining budget funds will cover organizational overheads in the

form of Programme Support Costs (PSC), evaluation related expenditures and project manage-

ment costs, which include the strategic planning process for a potential new phase of UN.GIFT.

e most substantial portion of these allocated funds (US$ 1.1 million) will be disbursed to Joint

Programme teams and spent over the next 12-16 months depending on underlying Joint

Programme timing.

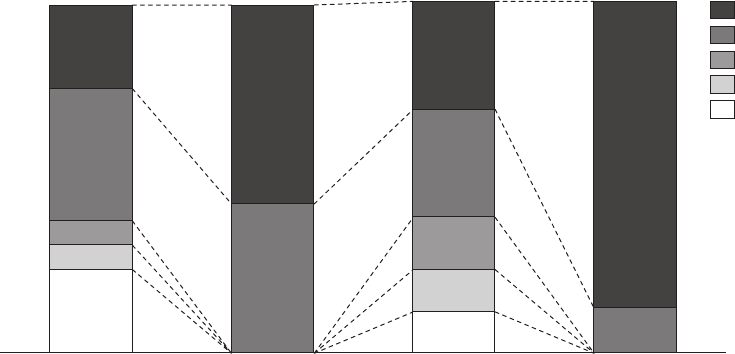

Table 2 below shows budgeted funds by output area (a total of US$ 12.3 million), excluding budgeted

administration and management related costs (US$ 3.2 million). In addition the gure shows actual

expenditures by output area until December 2010 (a total of US$ 10.5 million), excluding administra-

tive and management related costs.

e Project has been extended to allow for nal disbursements of funds and other relevant transition

activities over the rst few months of 2011. At that point, UN.GIFT will be renewed for an additional

phase or terminated.

e standard United Nations PSC rate is 13 per cent on trust fund expenditures or, in UNODC’s case,

special purpose fund (SPF) expenditures (E/CN.7/2009/13–E/CN.15/2009/23). e purpose of PSC

is to recover incremental indirect costs incurred to support United Nations activities nanced from

extra-budgetary donor contributions. Indirect costs covered by PSC are those that cannot be “traced

unequivocally to specic activities, projects or programmes,” including those incurred when perform-

ing the following functions: project appraisal and formulation; preparation, monitoring and adminis-

tration of work-plans and budgets; recruitment and servicing of sta; consultants and fellowships;

procurement and contracting; nancial operations, payroll, payments, accounts, collection of contri-

butions, investments of funds, reporting and auditing.

5

In rare circumstances, the PSC ratio can be

lowered beneath the default amount, which needs to be justied and approved by special permission

of the Assistant United Nations Secretary-General for Financial Services.

UN.GIFT’s PSC rate on its initial grant is an instance of such an exception. e initial grant was

lowered to a 5 per cent PSC rate, based on the justication that the UN.GIFT project budget had

built in substantial direct support and a large contingency element already captured as part of manage-

ment costs. Project related management costs (including 2011 forecasts) will add up to 14 per cent of

the project budget. In addition, planned expenditures related to the independent evaluation will

amount to 2 per cent of the project budget, in accordance with UNODC guidelines. Based on 2007-

2010 expenditures and 2011 forecasts, total overheads thus amount to 21 per cent of the total project

budget.

In the case of UN.GIFT, PSC revenues have been utilized as general organizational overhead for the

hosting of UN.GIFT, with recovered costs being allocated to various UNODC sections and eld

oces.

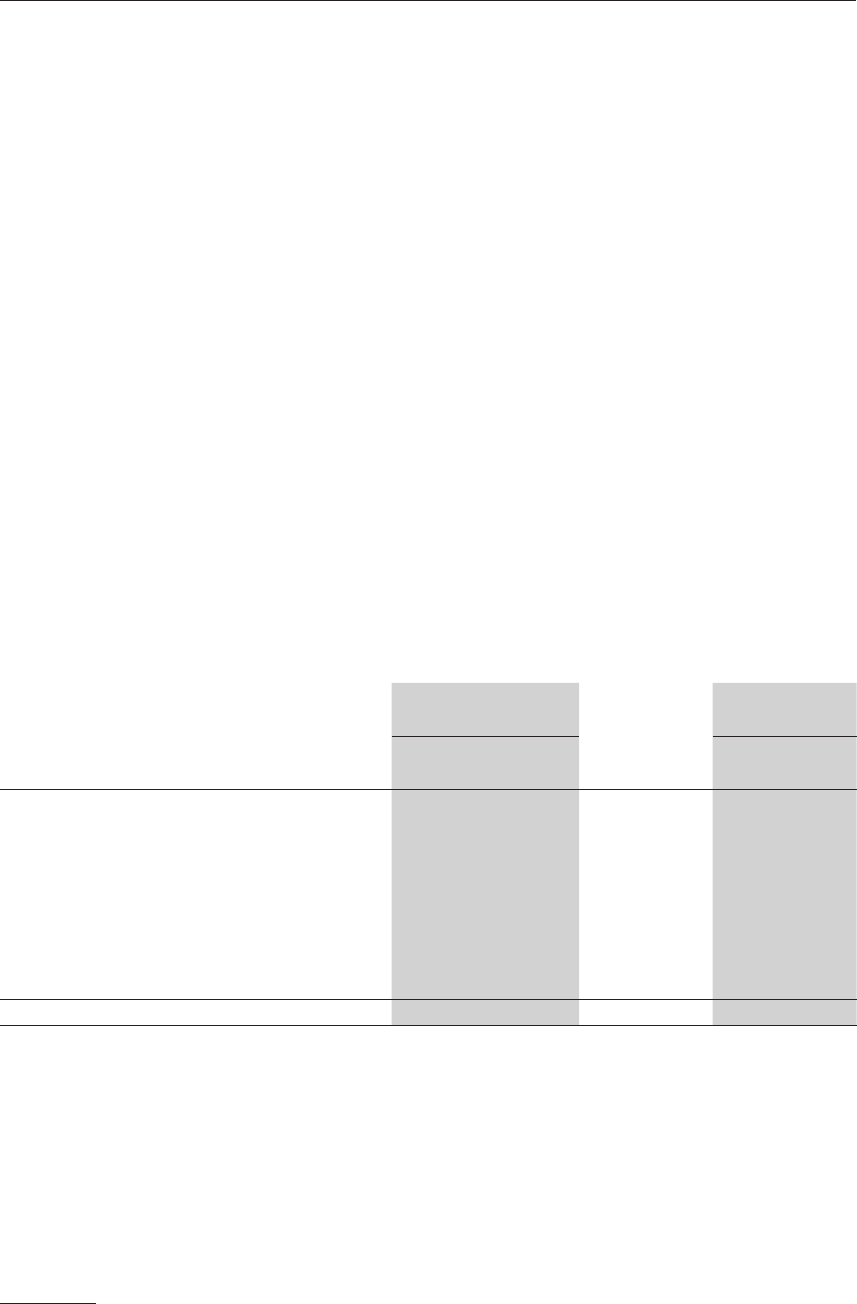

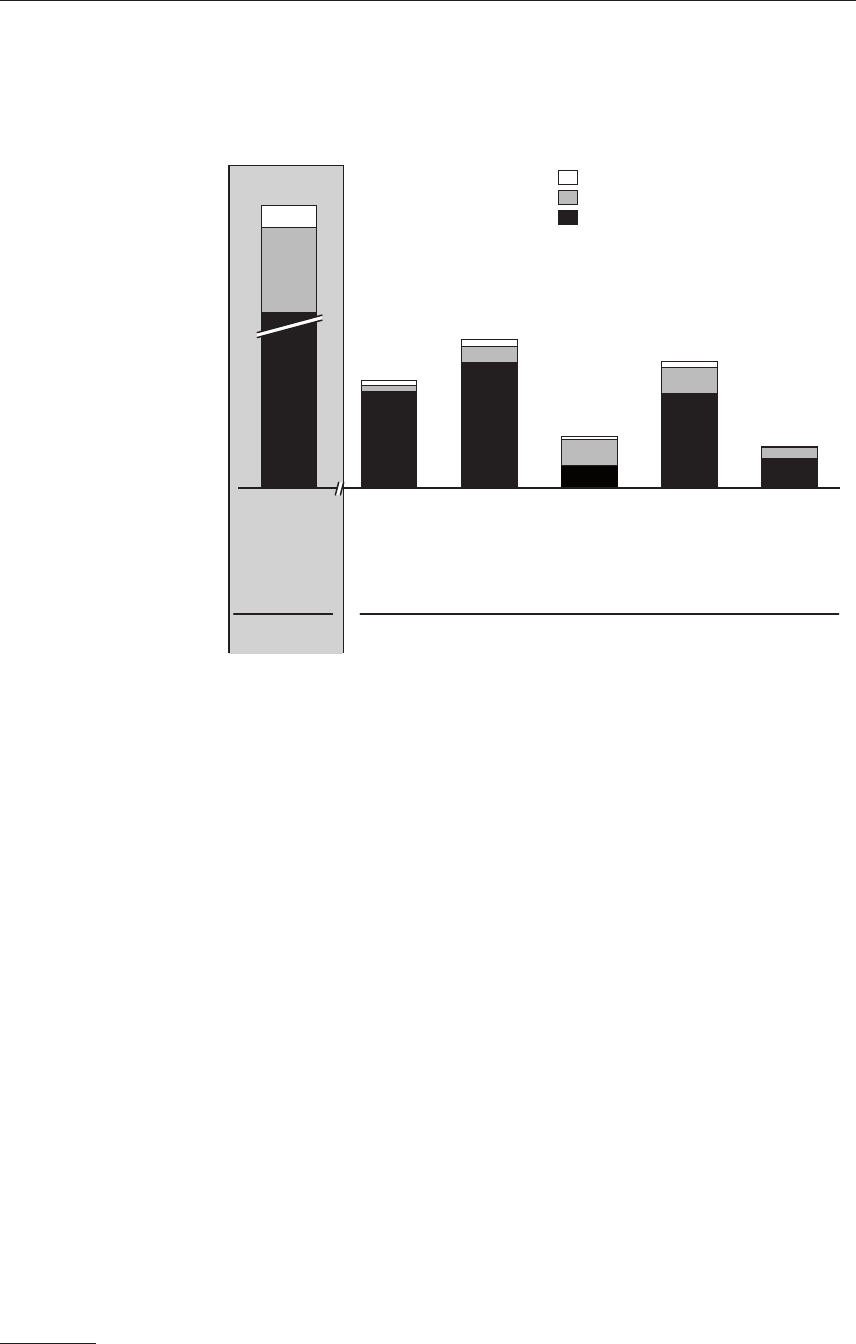

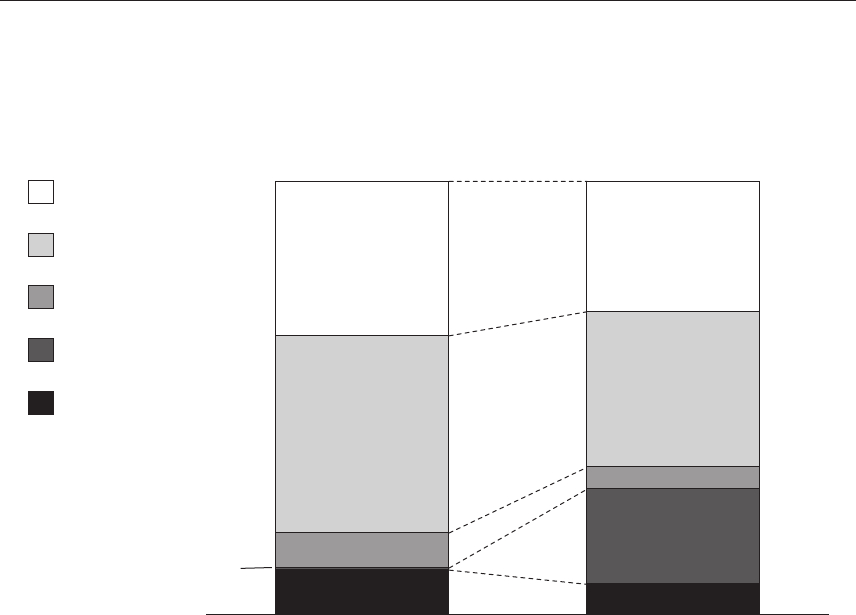

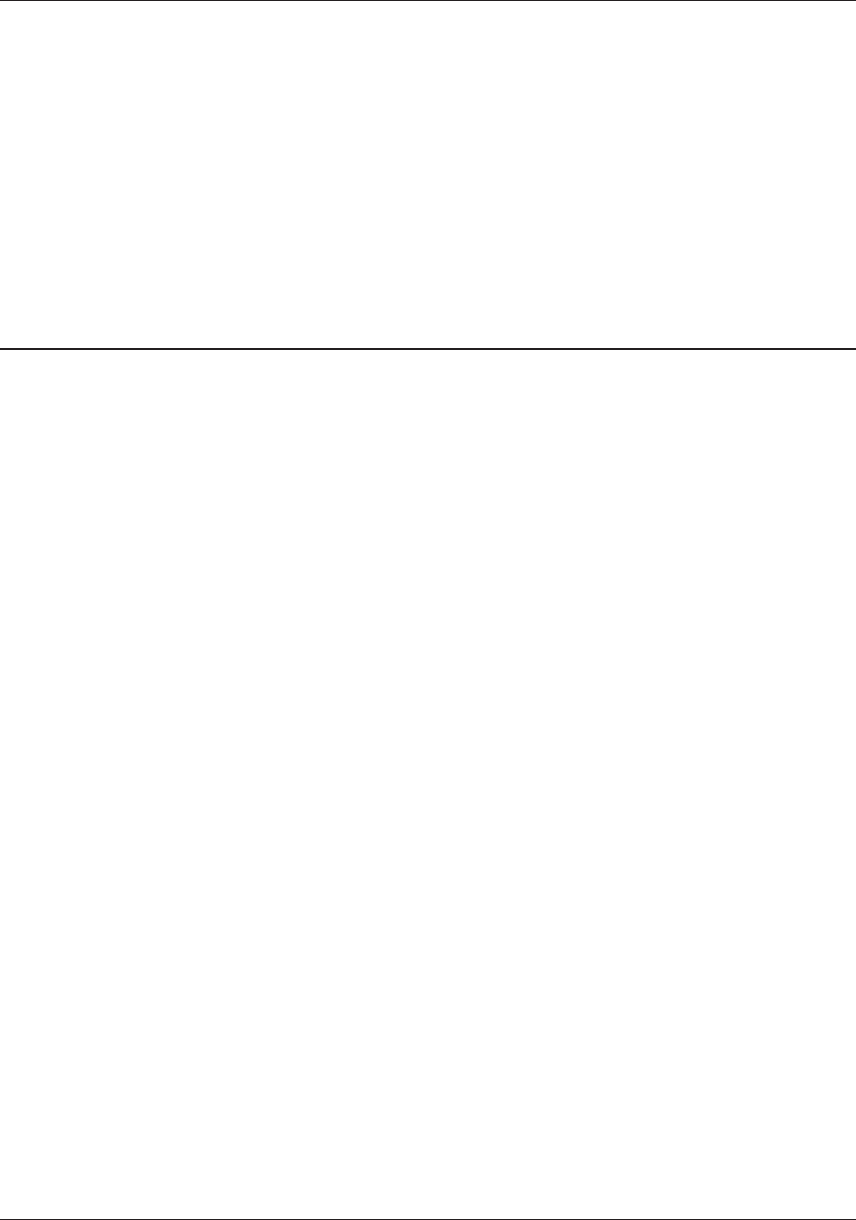

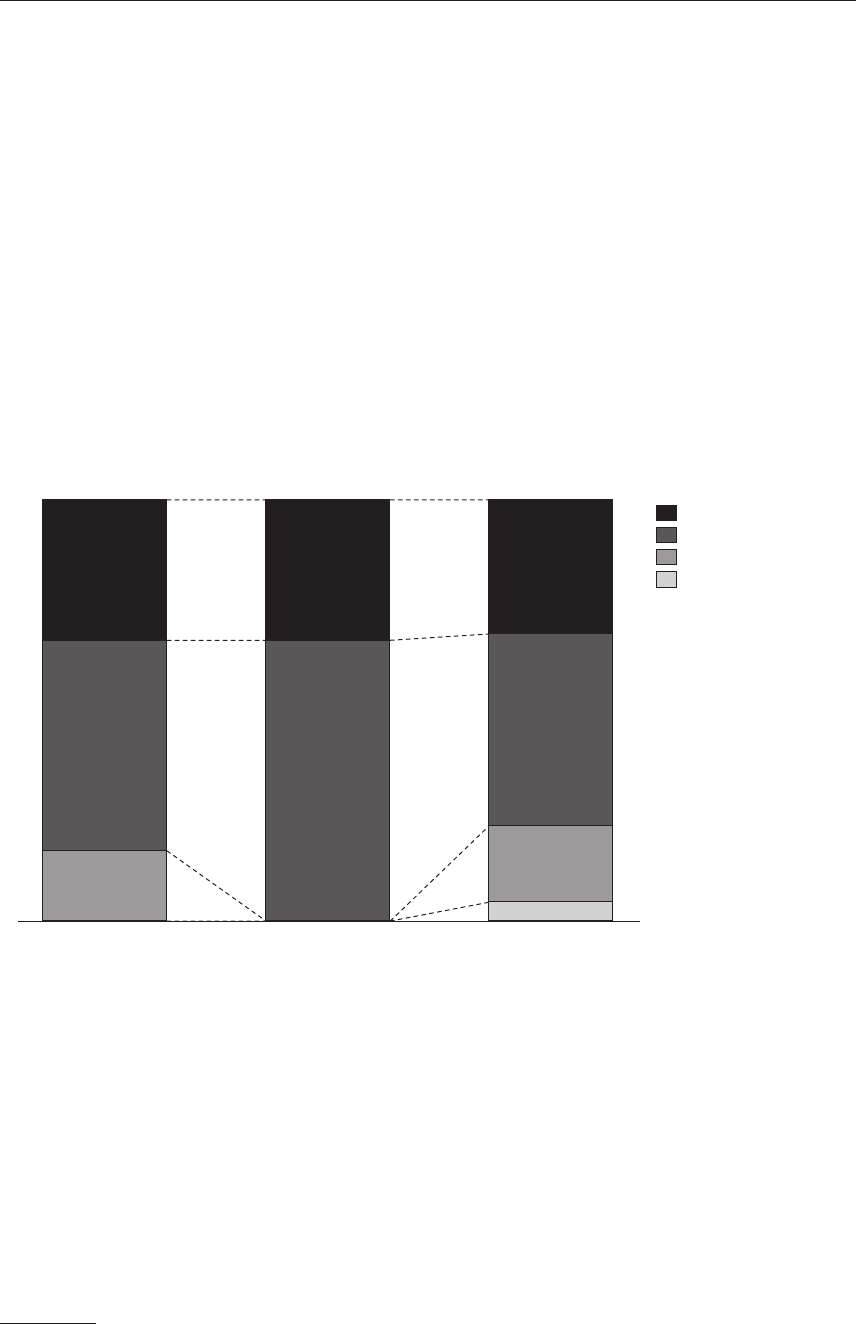

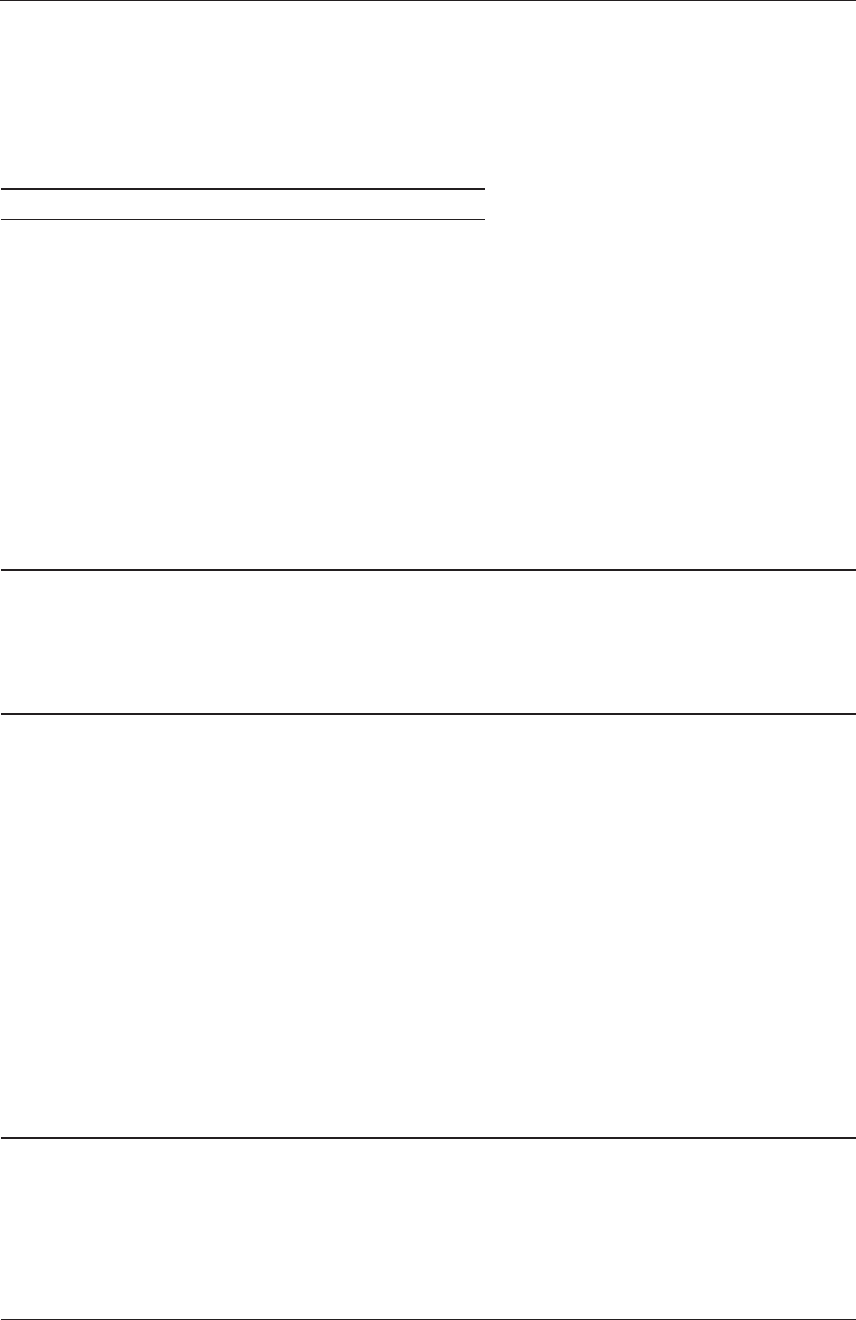

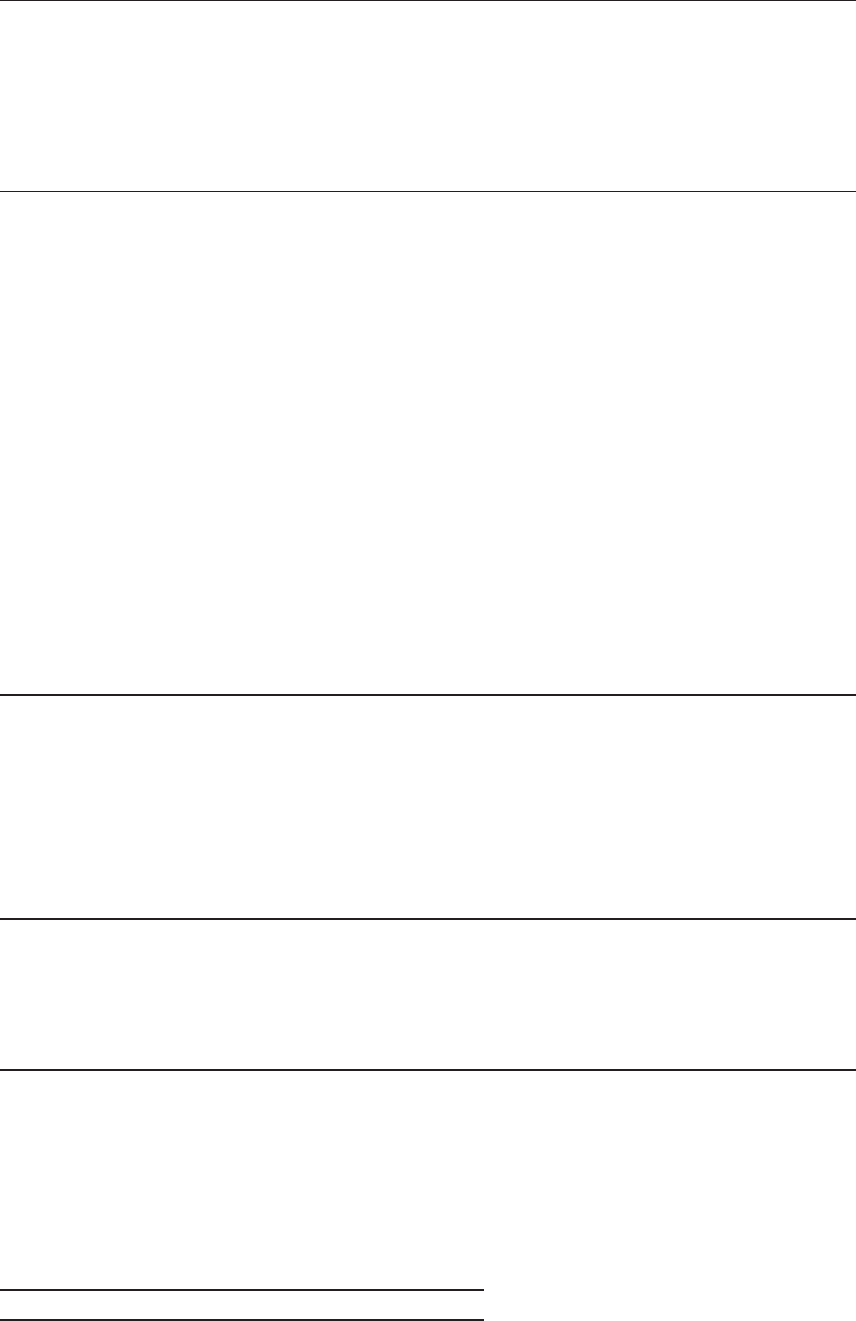

Figure IV below shows further detail on UN.GIFT expenditures over time and particularly identies

organizational overheads in the form of PSC, project management costs, and expenditures related to

the independent evaluation.

5

UNOV/UNODC, e Concept of Regular Budget and Extra-Budgetary Resources (Special Purpose Funds,

Programme Support Funds and General Purpose Funds, 2010.

7

IntroductIon

Outputs

Total budget by

output area

(US$ mil.,

percentage)

a

Expenditures till

Dec 2010

(US$ mil., percentage)

a

Major programme activities funded, facilitated, and/or implemented by UN.GIFT (not exhaustive)

1a. Increased awareness of

human trafficking

b

3.4 (27 per cent) 2.1 (20 per cent) • Extensive media campaigns including a BBC TV Series, 3 lms, and UN.GIFT PSAs broadcast

on 9 international news channels (CNN, TV5, Deutsche Welle, Xinhua, AP)

• Awareness-raising posters, brochures, publications, and advocacy materials

• Awareness-raising initiatives like the Gulu Project and Start Freedom Campaign

1b. Increased knowledge of

human trafficking

b

1.0 (10 per cent) • UN.GIFT Global TiPs Report covering 155 countries (major share of knowledge budget)

• Multiple reports including 5 content specic reports/research papers, several region-specic

• UN.GIFT website launched in 2008 and expanded with rich content with launch of Virtual

Knowledge Hub in August 2010 (receiving up to 16k monthly unique visitors)

2. Increase political

commitment and capacity

of Member States to

counter human trafficking

and implement the

Trafficking Protocol

5.1 (41 per cent) 1.1 (11 per cent) • 10 regional conferences, covering Africa, Eastern Europe/Central Asia, South Asia and Lat. Am.

2.7 (26 per cent) • 5 Joint Programmes (down from original plan for 6 JPs) focused on local capacity-building

(1 launched in 2010; 2 to be launched in early 2011; 2 in development stage)

• Capacity-building tools for AHT professionals and government ofcials—including 9 Expert

Group Initiative manuals and toolkits developed by UN.GIFT Steering Committee members

• Capacity-building events (e.g. parliamentarian training, 6 law enforcement trainings)

• Inter-agency coordination—regular coordination meetings (22 since programme launch ) for

UN.GIFT Steering Committee members representing many of the key players in AHT

• Women’s Leadership Council

3. Mobilize resources to

implement the action

required to combat

trafficking at international,

regional and national level

0.6 (5 per cent) 0.5 (5 per cent) • Fundraising events and partnership with UNF: US$ 509k raised towards UN.GIFT budget,

US$ 780,000 raised by the JP team in Serbia, over US$ 1.5 million in indirect donations and

co-funding

• 17 private partnerships, 8 active, e.g. Qatar Airways, Eurolines, Hilton Hotels, ongoing private

sector engagement and training, and facilitation of initiatives like the upcoming Tourism Industry

Code of Conduct in India

• Best practices on private partnership design

Table 2. Project budget, expenditures, and activities by output area

8

IN-Depth evaluatIoN: uN.GIFt

Outputs

Total budget by

output area

(US$ mil.,

percentage)

a

Expenditures till

Dec 2010

(US$ mil., percentage)

a

Major programme activities funded, facilitated, and/or implemented by UN.GIFT (not exhaustive)

4. Global Conference (i.e.

Vienna Forum)

2.3 (19 per cent) 2.3 (22 per cent) • Vienna Forum involving 1600 decision makers from 130+ countries, covered by 250+ media

outlets, with 6,000+ separate reports in media, and mentioned in multiple UN resolutions

5. Increase support to

victims of trafficking

through NGOs and other

service providers

0.9 (7 per cent) 0.7 (7 per cent) • Engagement and funding for global NGOs (e.g. Stop the Trafk), study exchanges for victim

support providers from Nigeria and UAE, Business Leader Awards

• Victim Translation Assistance Tool (MP3 audio tool)

• Small Grants Facility (US$ 529,000) launched with 440 applications, 12 grants in June of 2010

Total US$ 12.3 mil

a

US$ 10.5 mil

a

a

Budget and expenditures exclude management and PSC costs; total budget including management and PSC is US$ 15.5 mil, with expenditures of US$ 13.5 through Dec. 2010.

b

Output area 1 (“awareness and knowledge-building”) has been further sub-divided into 1a and 1b to facilitate transparency.

Source: Based on internal UN.GIFT Secretariat progress reports and tracking of expenditures; amounts may not exactly match UNODC nancial reporting system information.

9

IntroductIon

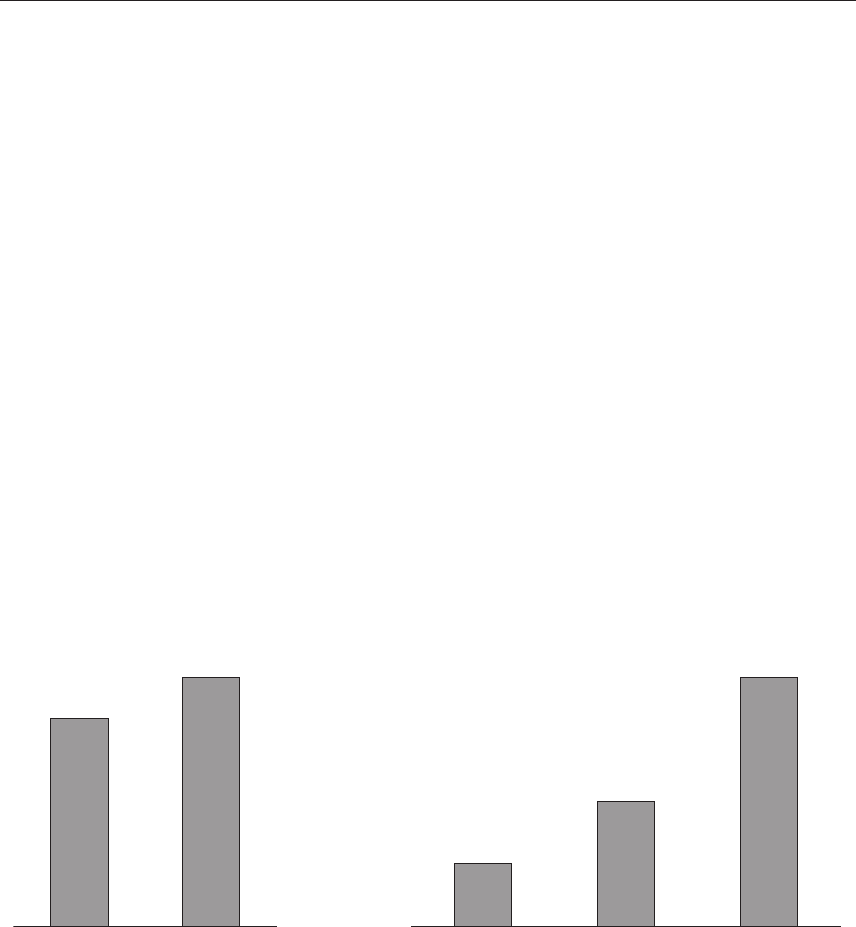

Figure IV. UN.GIFT expenditures 2007-2011 (in US$ millions)

2.4

2007

0.2

Total UN.GIFT

budget

3.8

12.3

15.5

0.1

0.1

2011(est.)

2.0

3.4

0.7

1.8

2010

2.7

2.0

0.2

0.6

2009

1.8

0.8

0.3

0.9

2008

5.2

4.4

0.1

0.6

0.1

Programme support costs

Management and evaluation costs

a

Programme expenditure on output areas

PSC (percentage)

Management and project

costs (percentage)

a

55554

16

a

11 50 822

US$ millions

Total overheads (percentage) 21 16 55 1227

5

6

11

a

Management costs include US$ 205k spent in 2010 on the evaluation of UN.GIFT and related strategic planning activity (2 per cent

of total budget).

Source: UN.GIFT Secretariat FRMS interim reports, UN.GIFT expenditure tracking, UN.GIFT Project Progress Reports; Dalberg

analysis.

Evolution of UN.GIFT

UN.GIFT has evolved signicantly over its rst three years of operations.

e original UN.GIFT Project Document called for three distinct phases of UN.GIFT (table 3):

(a) A preparatory phase focused on raising awareness, knowledge about human tracking,

identifying partners and mobilizing resources;

(b) A global stock taking phase in order to understand the priorities and key unmet needs of

stakeholders. is phase included the organization of a global conference on human tracking (the

Vienna Forum, planned originally for November 2007, but ultimately held in February 2008);

(c) An implementation phase focused on developing programmatic responses, partnerships and

coordination mechanisms in line with the priorities identied in the rst two phases.

In line with this plan, during the initial “preparatory” and “stock-taking” phases (2007-2008),

UN.GIFT focused on awareness-raising for the public and opinion makers, including ten regional

AHT conferences,

6

the Vienna Forum to Fight Human Tracking, a variety of public awareness

campaigns, and the launch of the UN.GIFT website.

6

e regional conferences have been categorized under the “political commitment and capacity-building” output area, but

like the Vienna Forum were mostly intended as a tool for political mobilization and awareness raising for decision makers.

10

IN-Depth evaluatIoN: uN.GIFt

UN.GIFT also funded, coordinated, and produced research and capacity-building tools on various

aspects of human tracking, with the most substantial knowledge investment being the funding of

the UNODC/UN.GIFT Global Report on Tracking in Persons.

A series of resolutions were passed early in the Project’s life in order to re-direct UN.GIFT activities

towards areas of greater strategic interest to Member States, specically technical assistance and

capacity-building.

Decision 16/1 of the Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (CCPCJ) in April 2007

stated “that the Global Initiative to Fight Human Tracking should be guided by Member States”.

Decision 16/2 in November 2007 stressed “the importance of conducting UN.GIFT in full compli-

ance with the mandate of and decisions of the Conference of Parties to the United Nations Conven-

tion against Translational Organized Crime” and requested “that the United Nations Oce on Drugs

and Crime to provide Member States, the Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice and

the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized

Crime with all information on the proceedings of the Vienna Forum as well as on progress and future

planning of UN.GIFT, including by providing reports on the meetings of the steering group and

reports of regional and expert group meetings”.

CCPCJ Resolution 17/1 on the “Eorts in the ght against tracking in persons”, requested “the

United Nations Oce on Drugs and Crime to continue consultations with Member States and to

ensure that the Global Initiative to Fight Human Tracking is carried out as a technical assistance

project within the mandates agreed by the relevant governing bodies and to brief Member States on

the work plan of the Global Initiative, to be executed before the end of the project, in 2009”.

Aside from these resolutions, the Project has also been subject to a number of revisions, most notably

in December 2007, March 2009, December 2009, and February 2010 formalizing the shift to techni-

cal assistance, increasing the size of UN.GIFT Secretariat, extending the Project’s duration to Decem-

ber 2010, and revising the Project’s activities in line with a new Strategic Plan approved by the

UN.GIFT Steering Committee in November 2009.

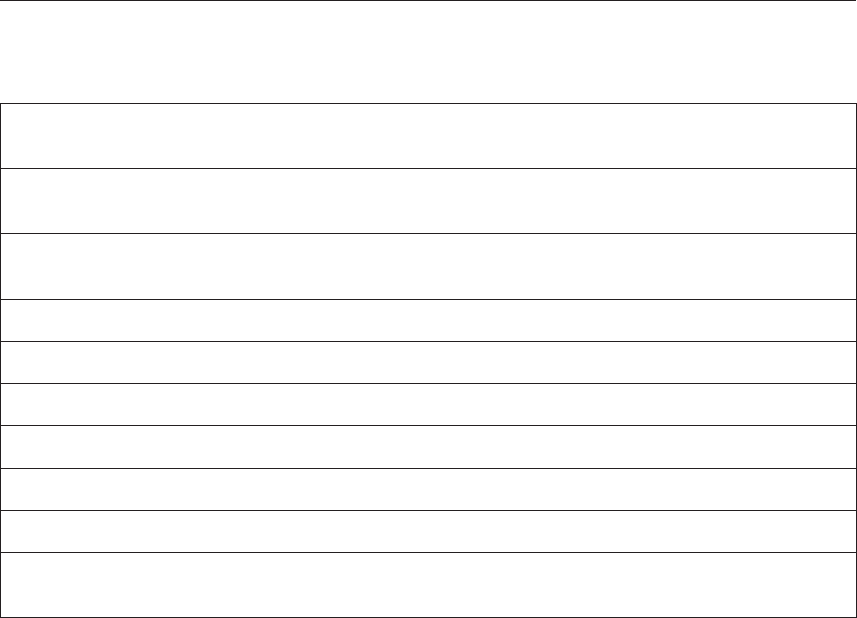

Table 3. Evolution of UN.GIFT (2007-2010)

Phases of the Programme

Preparatory Stocktaking

Implementation

Regional events designed to

strengthen anti-trafficking

networks and to generate

coordinated activities and build

momentum for a global

campaign and conference on

human trafficking

A centerpiece of UN.GIFT, with

the organization of a major

global event, the Vienna

Forum to Fight Human

Tr afficking, and a global data

collection exercise on the

world state of human

trafficking

Builds on the political will, the

partnerships and global

networks generated in

previous phases to drive a

results oriented agenda and

support capacity-building

projects

Major project revisions

Sept.-Dec. 2007 Senior Manager appointed; MS direct UN.GIFT to cancel several activities (e.g. establishment of an

AHT fund), delay the Vienna Forum to February 2008, and resolve that the effort should be managed as a

technical assistance project with increased focus on capacity building

March 2009 No cost extension of the project by 9 months till 31 Dec. 2009; UNODC to continue consultations with MS

and to ensure that UN.GIFT is carried out as a technical assistance Project (restated in GA resolution 63/194)

Dec. 2009 No-cost extension of the Project until 31 Dec. 2010; restructuring of outputs and activities in line with a new

Strategic Plan approved by the UN.GIFT Steering Committee; some changes in monitoring and reporting

11

IntroductIon

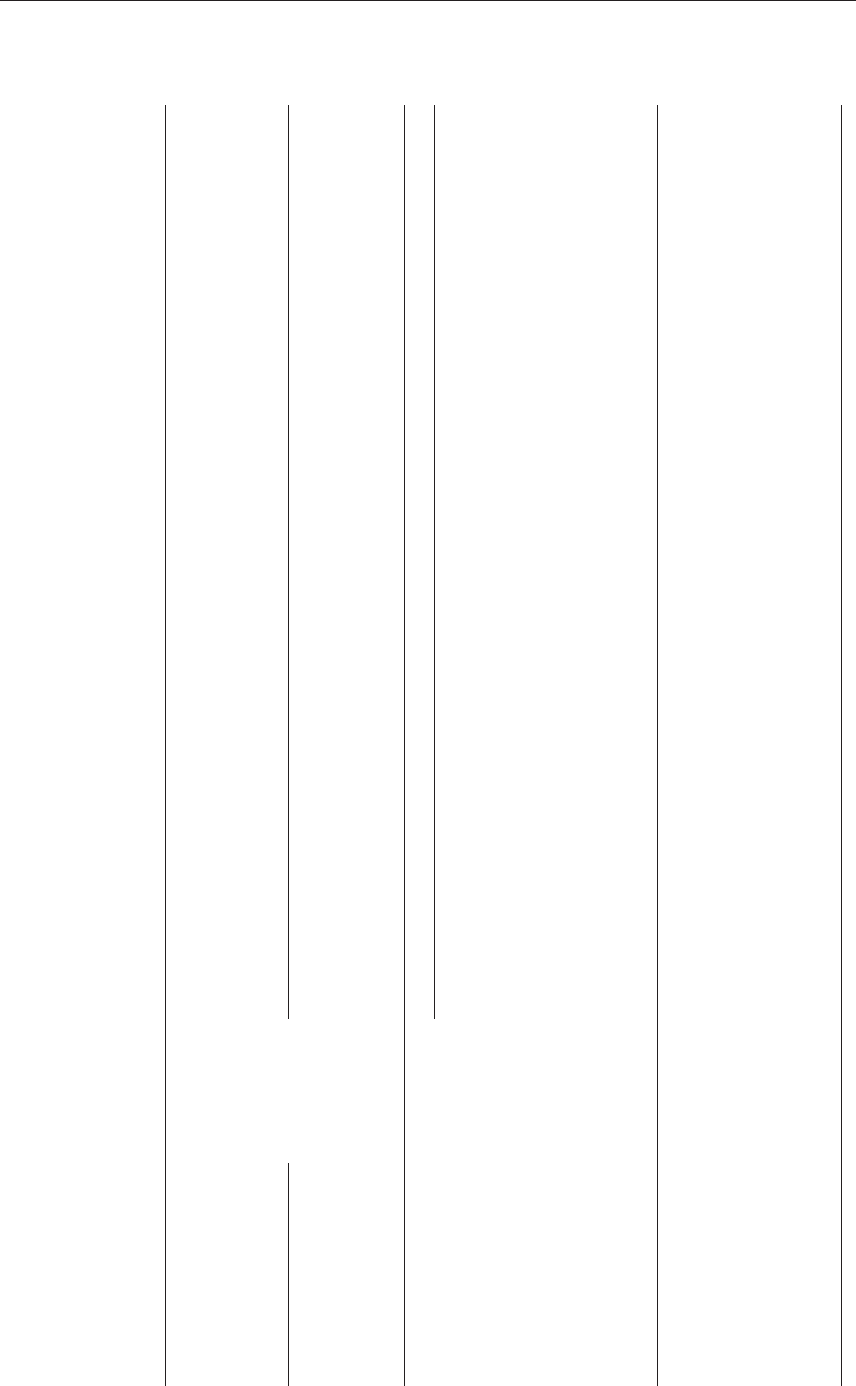

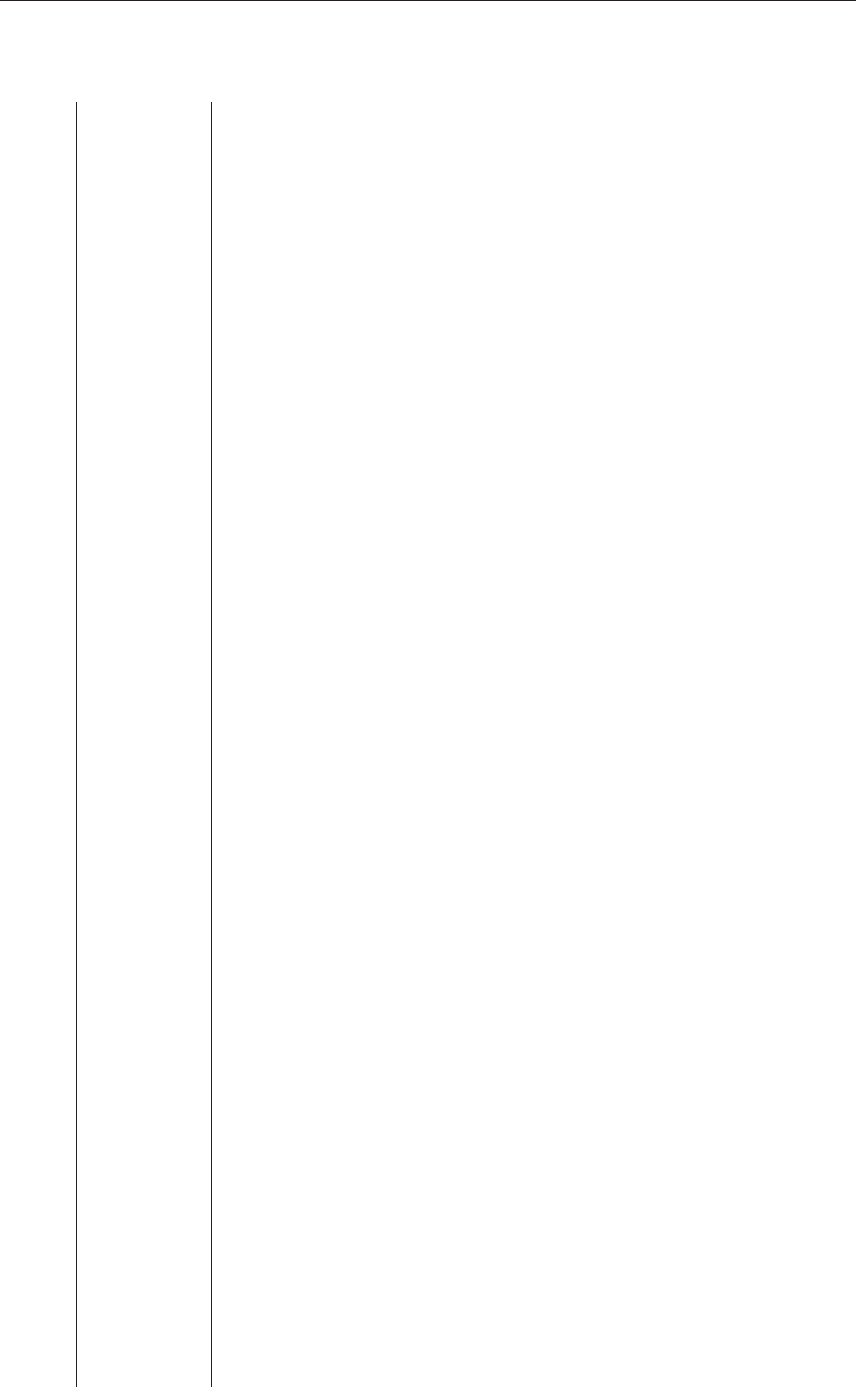

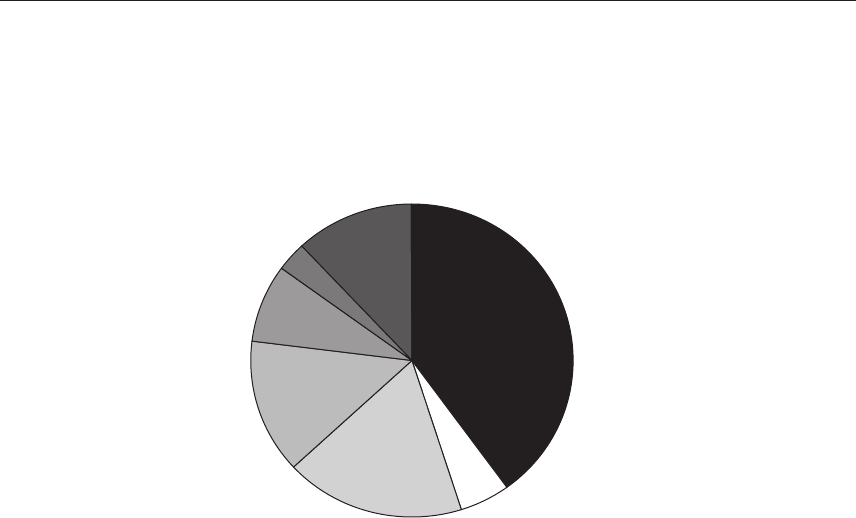

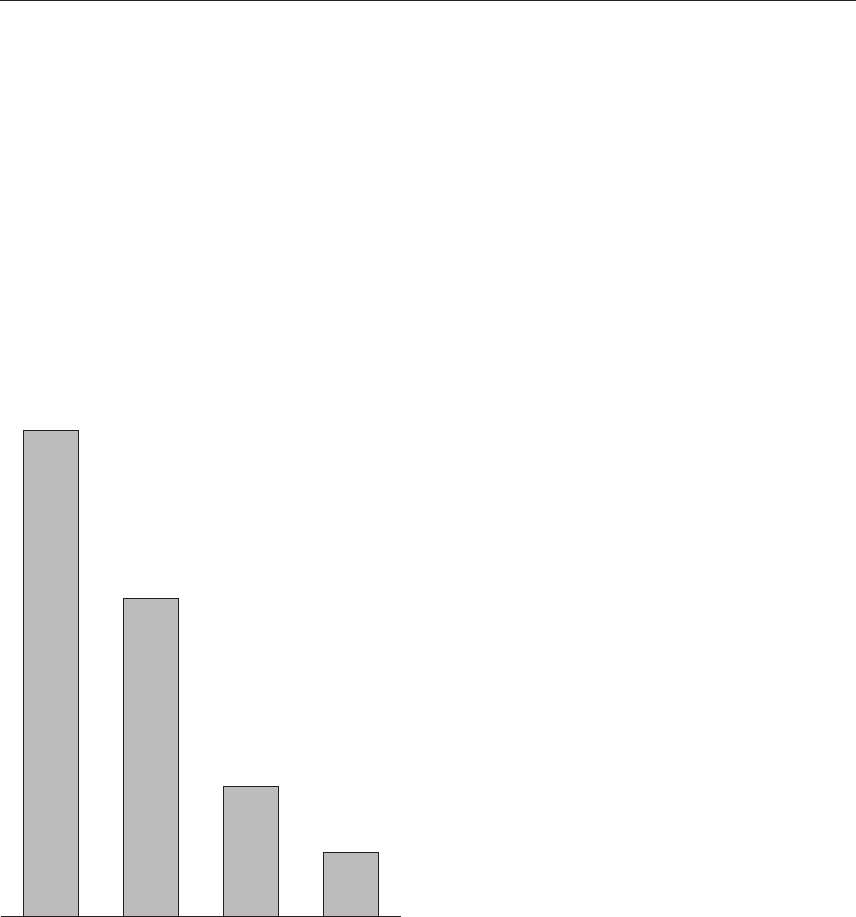

In accordance with these resolutions and revisions and broadly in line with the Project’s original plans

for an “implementation” phase, UN.GIFT priorities shifted in late 2008 toward capacity- building and

technical assistance, as reected in increased expenditures for Output Area 2 (gure V). While con-

tinuing to carry out awareness-raising and knowledge eorts, UN.GIFT began to shift its resources to

developing Joint Programmes at the national or regional levels, mobilizing global and national public-

private partnerships, and launching a Small Grants Facility for NGOs with a focus on prevention and

victim support.

7

7

e UN.GIFT Small Grants Facility (SGF) focuses on four activity lines as agreed to by the SC, namely (i) the empow-

erment of vulnerable groups and communities, (ii) direct victim support, (iii) cooperation between NGOs from countries of

origin and destination, and (iv) collection of evidence-based knowledge.

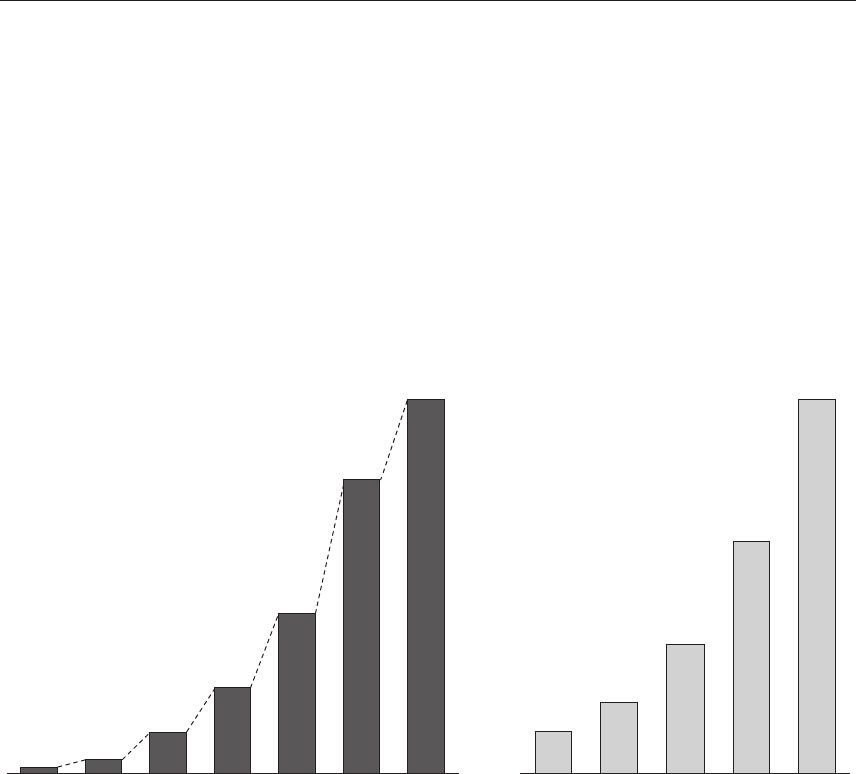

Figure V. Shift of expenditures to capacity-building and victim support after 2008

100% =

6%

33%

8%

8%

7%

9%

44%

11%

5. Victim support structures

3. Mobilize resources

2. Increase political commitment

and build capacity

2009

43%

2.0

2010

(through Dec.)

16%

12%

72%

1.8

4. Global Conference

Budget remaining

as of Dec. 2010

1. Increase awareness and

knowledge

0.8

70%

19%

2008

4.4

22%

32%

2007

3.4

43%

b

(14%)

38%

a

Excludes management costs, evaluation fees, and PSC; expenditure per output calculated based on the UN.GIFT project team’s

internal monitoring of expenditures.

b

Includes US$ 1.1 million of regional conference spending (29 per cent of total), with balance of funds (14 per cent of total) spent

on capacity-building and TA activities.

Source: UN.GIFT team analysis.

It is important to note that the regional conferences in 2007, with nearly US$ 1.1 million of expendi-

tures, particularly focused on raising awareness of regional decisionmakers, knowledge-sharing and

boosting political commitment. However, due to the shortcomings of the logical framework, they

were categorized under the “capacity-building” output area (2) and therefore obscure the shift to tech-

nical assistance after 2007, which was in fact substantial. Adjusting for the regional events, technical

assistance spending has increased from a negligible portion of the US$ 3.4 million spent on Project

activities in 2007 (14 per cent), to 22 per cent of the US$ 4.4 million spent in 2008 to 43 per cent of

direct project expenditures in 2010 (gure V).

12

IN-Depth evaluatIoN: uN.GIFt

Evaluation scope, methodology and limitations

e independent evaluation of UN.GIFT was initiated by the UN.GIFT Secretariat in accordance