Financing the UN Development System

Time for Hard Choices

September 2019

United Nations

MPTF Oce

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily

represent those of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, the United Nations,

(including the United Nations Development Programme)

the Multi-Partner Trust Fund Oce or the UN Member States.

Design of figures and illustrations

Pär Jansson and Kristin Blom

Illustrations

Cover, and all small labyrinth illustrations: Adobe Stock Images

Copy Editor

Emma Naismith

Printer

X-O Graf Tryckeri AB

Uppsala, Sweden

August 2019

ISBN

978-91-985372-1-5

Financing the UN Development System

Time for Hard Choices

5

This fth annual report, Financing the UN Development System 2019: Time for Hard Choices

is produced through a collaborative partnership between the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation

(the Foundation) and the United Nations Multi-Partner Trust Fund Oce (MPTFO).

The lead authors of the 2019 edition of the report were Bruce Jenks (Senior Advisor to the

Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation) and Jennifer Topping (Executive Coordinator of the MPTFO).

Veronika Tywuschik-Sohlström (Programme Manager) acted as production lead for the report,

supported by Sigrid Gruener (Programme Director) and Henrik Hammargren (Executive

Director), all three from the Foundation.

Part One was developed and led by MPTFO colleagues Henriette Keijzers (Deputy Executive

Coordinator), Per Andersson (Senior Advisor), Diana Fajardo-Ardila (Data Analyst) and Per Jentzsch

(Data Analyst).

The look of the report is thanks to Kristin Blom (Communication Manager) at the Foundation.

Annika Östman (Communication Manager) and Anna Crumley-Enger (Communications and

Programme Coordinator) provided useful reections on the content together with all lead authors.

Johanna Mårtendal (Programme Assistant) helped with thorough proofreading.

The Financing the UN Development System 2019: Time for Hard Choices report was made all the richer

by the contributions, expertise, and ideas from a wide array of partners from near and far.

A special thank you to our guest authors, who generously contributed with their insights on

current nancial trends. A sincere thanks to: Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Max-Otto Baumann,

Fiona Bayat-Renoux, Michael Bennett, Franck Bousquet, Henk-Jan Brinkman, Laura Buzzoni,

Pedro Conceição, Brian Elliott, Philipp Erfurth, Rebeca Godoy, Navid Hanif, Catherine Howell,

Homi Kharas, Erik Lundsgaarde, Ayham Al Maleh, John W. McArthur, Ulrika Modéer,

Michael Møller, Ambassador Lana Zaki Nusseibeh, Jonathan Prentice, Ambassador E. Courtenay

Rattray, Maximilian Sandbaek, Guido Schmidt-Traub, Silke Weinlich, and Kanni Wignaraja.

Last but not least, this publication would not have been possible without the close partnership

with Laura Gallacher from the Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB) Secretariat and

Andrew MacPherson from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs

(UNDESA) who kindly provided us with the CEB and UNDESA data used for the gures and

tables found in Part One of this report.

Acknowledgements

6

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... 5

OVERVIEW OF FIGURES & TABLES ...................................................................................... 8

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................10

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 22

PART ONE: ........................................................................................................................ 25

OVERVIEW OF UNITED NATIONS' RESOURCE FLOWS ....................................................... 26

CHAPTER ONE: REVENUE ..................................................................................................27

CHAPTER TWO: EXPENDITURE...........................................................................................52

CHAPTER THREE: MOVING AHEAD ON DATA QUALITY .................................................... 58

PART TWO: ....................................................................................................................... 65

OVERVIEW OF PART TWO .................................................................................................. 66

CHAPTER ONE: FINANCING THE 2030 AGENDA: THE BIG PICTURE .................................70

International nancing of the Sustainable Development Goals

By Homi Kharas ........................................................................................................................................... 71

The United Nations Secretary-General’s strategy for nancing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

By Fiona Bayat-Renoux ............................................................................................................................... 74

Investment Gapportunities: Changing the narrative on investment in sustainable development

By Navid Hanif and Philipp Erfurth.............................................................................................................. 79

Driving development nance to the ground: Closing the investment gap

By Ambassador E. Courtenay Rattray ............................................................................................................ 86

Bye-bye, billions to trillions

By John W. McArthur ................................................................................................................................... 90

How does science and technology policy shape inequality?

By Pedro Conceição ..................................................................................................................................... 93

Table of contents

7

Table of contents

CHAPTER TWO: EARMARKING: MAKING SMART CHOICES .............................................100

UN pooled funding:

‘Healthy’ nancing for better multilateral results

By the UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund Oce (MPTFO) .............................................................................. 101

Shades of grey: Earmarking in the UN development system

By Max-Otto Baumann, Erik Lundsgaarde and Silke Weinlich .................................................................... 106

Improving the World Health Organization’s nancing

By Brian Elliott and Maximilian Sandbaek .................................................................................................. 110

Lessons from health on how to invest wisely in development

By Guido Schmidt-Traub ........................................................................................................................... 115

Current and future pathways for UN system-wide nance

By Silke Weinlich and Bruce Jenks .............................................................................................................. 119

CHAPTER THREE: FINANCING PEACEBUILDING,

HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND MIGRATION: TIME TO INVEST ...............................124

Financing t for the future: A 10-point Agenda for Financing Peacebuilding

By the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation ...................................................................................................... 125

The World Bank Group and the IDA18: Scaling-up support to address Fragility, Conict and Violence

By Franck Bousquet ................................................................................................................................... 128

Innovative nance for peacebuilding: It is time to invest

By Catherine Howell and Henk-Jan Brinkman ........................................................................................... 131

Ocial Development Assistance and peacebuilding: 10-year trends

By Ayham Al Maleh .................................................................................................................................... 136

How the Peacebuilding Fund is investing in the Sustainable Development Goals

By Laura Buzzoni and Henk-Jan Brinkman ................................................................................................ 141

OECD's Total Ocial Support for Sustainable Development pilot study on peace and security ...............................146

Financing the humanitarian-development-peace nexus

By the UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund Oce (MPTFO) .............................................................................. 148

Forecast-based nancing: A breakthrough at last for humanitarian nancing?

By Lana Zaki Nusseibeh ............................................................................................................................. 153

World Bank catastrophe bonds as an innovative development nancing tool

By Michael Bennett and Rebeca Godoy ..................................................................................................... 156

The Migration Fund: Building on the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration

By Jonathan Prentice .................................................................................................................................. 160

CHAPTER FOUR: MULTILATERALISM ON TRIAL? .............................................................162

A resolute resolution for multilateralism – a perspective from International Geneva

By Michael Møller...................................................................................................................................... 163

A brief reection on multilateralism, the UN and nancing

By Ulrika Modéer ...................................................................................................................................... 165

Multilateralism: An instrument of choice

By Bruce Jenks ........................................................................................................................................... 168

The crisis of multilateralism, viewed from the Global South

By Adriana Erthal Abdenur ......................................................................................................................... 172

Attracting the millennial investor to multilateralism and investing in the Sustainable Development Goals

By Kanni Wignaraja .................................................................................................................................... 174

CONCLUSION .................................................................................................................... 177

ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................178

ENDNOTES FOR PART ONE ...............................................................................................180

NOTES TO FIGURES AND TABLES IN PART ONE ............................................................... 182

8

Overview of figures and tables

in Part One

Figures

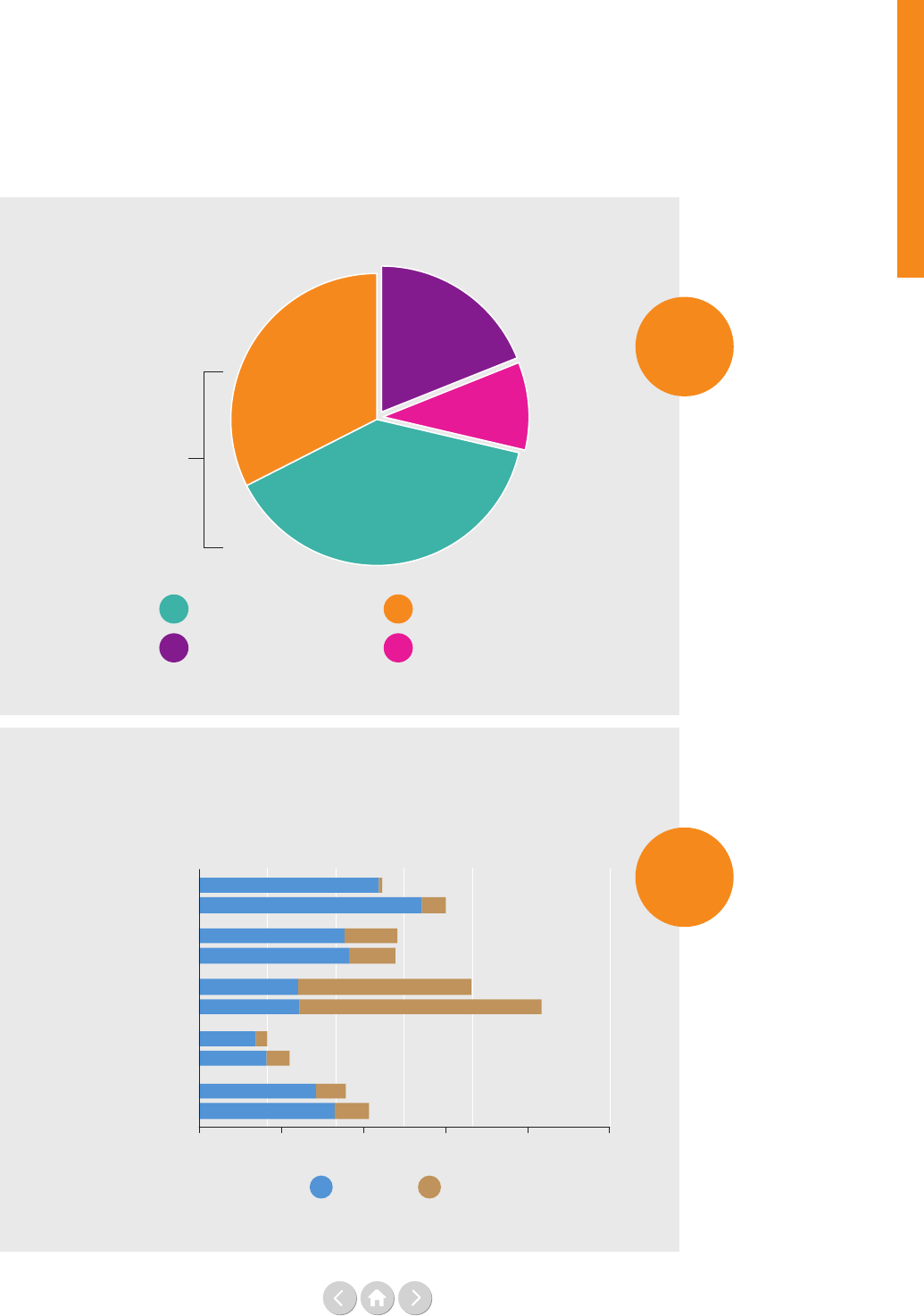

Figure 1: Overview of the total revenue of the UN system by nancing instrument, 2017 ............................ 29

Figure 2: Distribution of total UN system revenue, by nancing instrument, 2010–2017 .............................. 29

Figure 3: UN operational activities’ share of total revenue of the UN system by

nancing instrument, 2017 (Total US$ 53.2 billion) ..................................................................................... 32

Figure 4: Total core and earmarked contributions for UN operational activities, 2000–2017 . ........................ 35

Figure 5: Funding of UN system-wide activities, 2017 .................................................................................. 36

Figure 6: Total contributions for development and humanitarian-related

UN operational activities, 2000–2017 .......................................................................................................... 37

Figure 7: Real growth of ODA and of funding for UN operational activities

for development, 2000-2017 ........................................................................................................................ 37

Figure 8: Global humanitarian assistance ows, 2007–2018 .......................................................................... 38

Figure 9: Channels of total multilateral assistance from OECD-DAC countries, 2017 .................................. 39

Figure 10: Channels of total multilateral assistance from OECD-DAC countries,

core and earmarked, 2013 and 2017 .............................................................................................................. 40

Figure 11: Funding sources for UN operational activities, 2017 ..................................................................... 41

Figures 12-17: Non-state revenue of six selected UN entities, 2017 ............................................................. 42

Figure 18: Sources of ODA within 12 largest OECD-DAC members, as proportion of total, 2017 ................ 43

Figures 19-24: Funding sources within 6 OECD-DAC contributing countries nancing ODA, 2017 ........... 44

Figure 25: Funding mix of the top 12 OECD-DAC members to UN operational activities, 2017 ................. 45

Figure 26: Funding mix of the top 12 non OECD-DAC countries contributing to UN

operational activities, 2017 ............................................................................................................................ 46

Figure 27: Why a Funding Compact? .......................................................................................................... 47

Figure 28a and 28b: Development assistance funding mix of the top 20 contributors to the UNDS,

including assessed contributions, 2017 ........................................................................................................... 48

Figure 29: Total core contributions from the top ten OECD-DAC countries

to six selected UNentities, 2017 ................................................................................................................... 50

Figure 30: Total core contributions from the top ten non OECD-DAC countries

to six selected UN entities, 2017 ................................................................................................................... 50

Figure 31: Total earmarked contributions from the top ten OECD-DAC donors

to six selected UN entities, 2017 ................................................................................................................... 51

9

Figure 32:

Total earmarked contributions from the top ten non OECD-DAC countries

to six selected UN entities, 2017 ................................................................................................................... 51

Figure 33: Deposits to UN inter-agency pooled funds, 2010–2017 ............................................................... 52

Figure 34: Deposits to UN inter-agency pooled funds from the 12 largest contributors, and share

of their total earmarked contributions to the UN, 2017 ................................................................................. 53

Figure 35: Countries contributing more than 10% of their total earmarked funding to the UN

through UN inter-agency pooled funds, 2017 ............................................................................................... 53

Figure 36: Expenditure on UN operational activities by region, 2017 ........................................................... 54

Figure 37: Expenditure on UN operational activities by countries’ income status, 2017 ................................. 56

Figure 38: UN operational and peace related expenditure in crisis-aected countries, 2017 .......................... 57

Figure 39: Simplied representation of ows reported by multilateral institutions

in ODA and TOSSD ..................................................................................................................................... 61

Figure 40: Estimates of double counting in the UN system’s total 2017 revenue ........................................... 62

Figure 41: UN Data Standards and the Funding Compact ............................................................................ 63

Overview of figures and tables

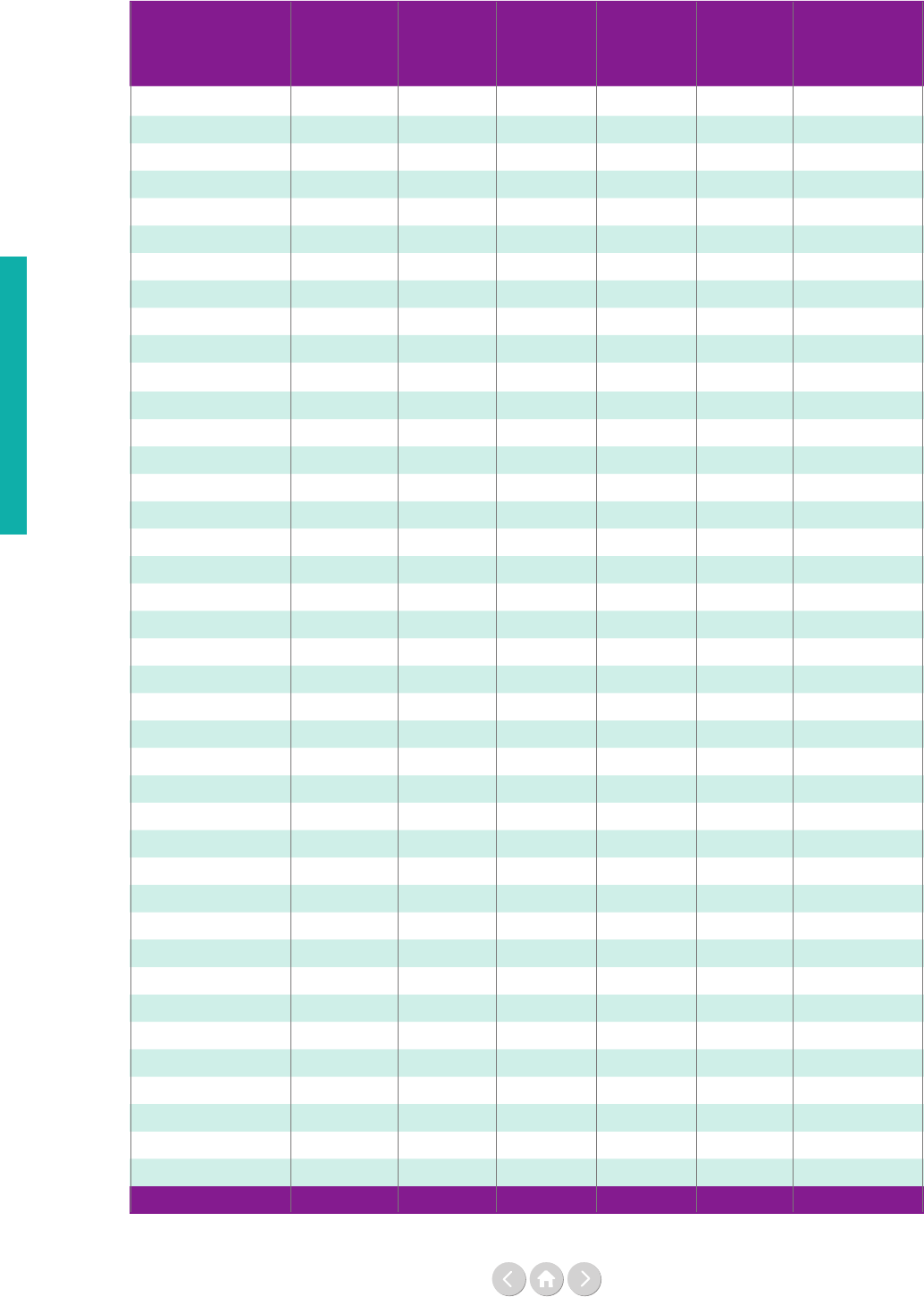

Tables

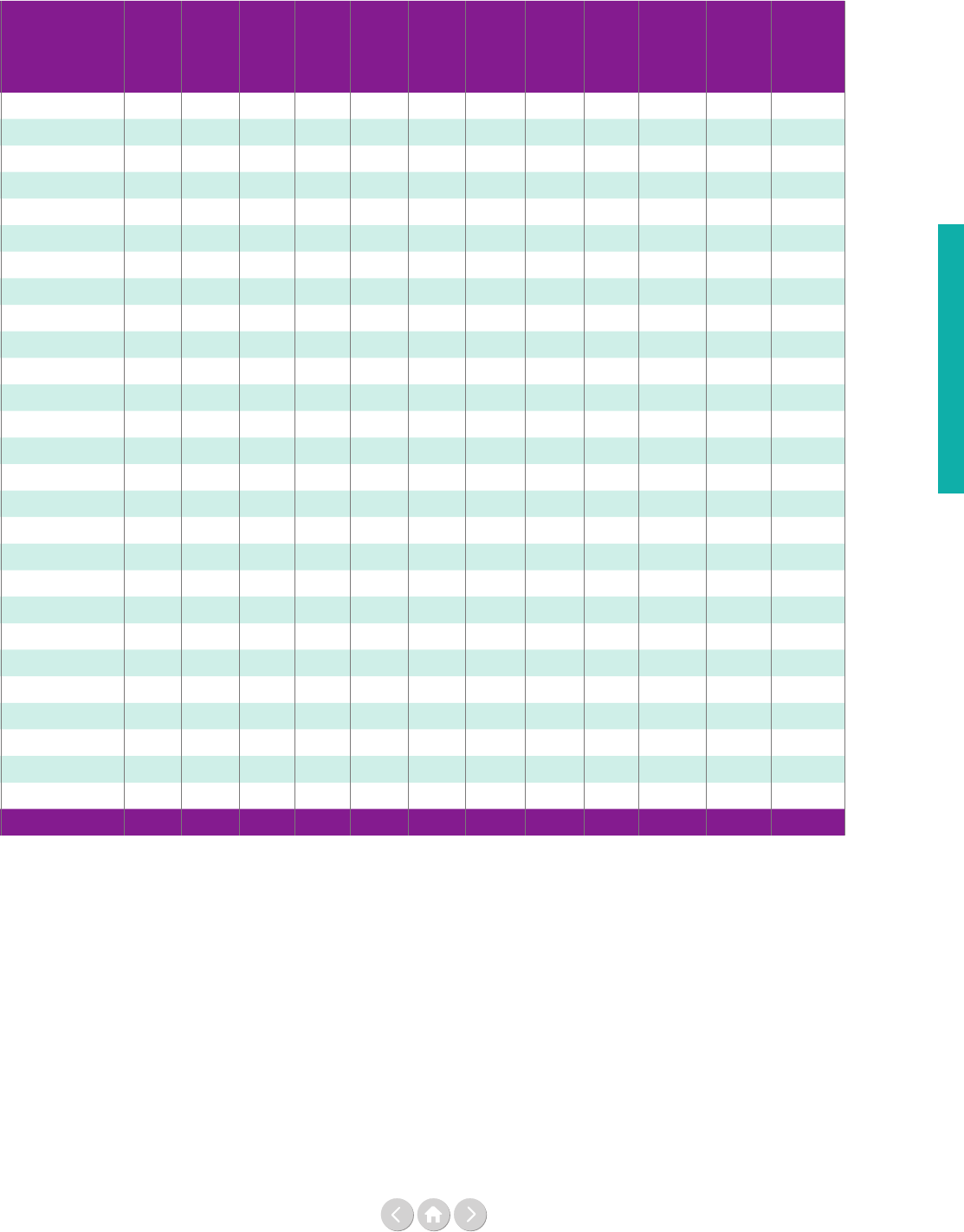

Table 1: The spectrum of UN nancing instruments ..................................................................................... 27

Table 2a: Total revenue of the UN system by entity and by nancing instrument, 2017 (US$ million) ......... 30

Table 2b: Total revenue of seven UN entities, 2017-2018 (US$ million) ....................................................... 31

Table 3: Assessed contributions to the UN system by entity, 1975-2017 (US$ million) ................................. 33

Table 4: Earmarked contributions to the UN system by entity (US$ million) .............................................. 34

Table 5: Five year perspective of Total Multilateral Aid from OECD-DAC countries (US$ billion) ............... 39

Table 6: Total expenditure by UN entity, 2005-2017 (US$ million) .............................................................. 55

10

Executive summary

trends impacting the SDGs. These are organised into

four dierent chapters. Emerging issues this year are how

nancing can more eectively support a ‘leave no one

behind’ agenda and how the ‘big picture’ of nancial

ows to developing countries inuences the role of the

UNDS in dierent country contexts.

This part of the report also dives deeply into the

challenges and opportunities for nancing related to

conict prevention and peacebuilding. In addition, it

looks at the role of nancing as it relates to technology,

digitalisation, science and for the rst time at the

purposeful investment choices of young millennial

investors. Together these essays provide analysis and

insights that we believe make an important contribution

to the debate and to the choices that lie ahead.

Key findings Part One:

Overview of United Nations’ resource flows

Chapter One: Revenue

The total revenue received by the UN in 2017 was

US$ 53.2 billion and represented an increase of

US$ 3.9 billion compared to 2016 (Table 2a). The

increase can be partly attributed to three factors:

First, six new UN entities are reporting to the Chief

Executives Board for Coordination (CEB) for the rst

time in this year’s report adding a total of US$ 0.5

billion to the overall revenue. Second, ‘double counting’

in the UN nancial system makes the UN total revenue

seem larger than it is; specic instances of where the

same nancial ows are reported by two UN entities

to the CEB are analysed in more detail in the third

chapter on data quality. And lastly, the overall revenue

of many UN entities has grown between 2016 and 2017,

with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

and the World Health Organization (WHO) having the

highest growth rate among six large UN entities

(35% and 17% respectively).

An important challenge is embedded in the

title of this year’s report:

Time for Hard Choices.

In a financing world which is both simple

and complex, the choices are numerous and

what follows are hard decisions about the

allocation of resources. A multilateral

approach to today’s global challenges will

need to use evidence to show its competitive

advantage. From here on, the financing

questions flow.

The intention of this report is to wake us up to the

reality that the nancing of the United Nations

development system (UNDS) is currently in the

spotlight of a complex reform agenda. At the same time,

nancing is a crucial dimension of a multilateral

approach to addressing the world’s urgent development

challenges. The report showcases the complexities and

inno vations within Sustainable Development Goal

(SDG) nancing and the need for a rm multilateral

approach when it is best for SDG achievement.

Scope of the report

This, the fth edition of Financing the UN Development

System report, is, as in previous years, divided into two parts.

Part One provides accessible UN funding data on

revenue and expenditures, which we believe is important

for understanding current and future nancing reform

discussions. This year’s report includes references to two

new initiatives in the UNDS funding landscape, the

Funding Compact and the 1% levy on tightly earmarked

contributions. It also discusses the quality issues of

nancial data, the adoption of new UN data standards

and why it matters.

In Part Two of the report, 25 prominent guest authors

from outside and inside the UN system present their

ideas and initiatives in concise essays on the nancing

11

Executive summary

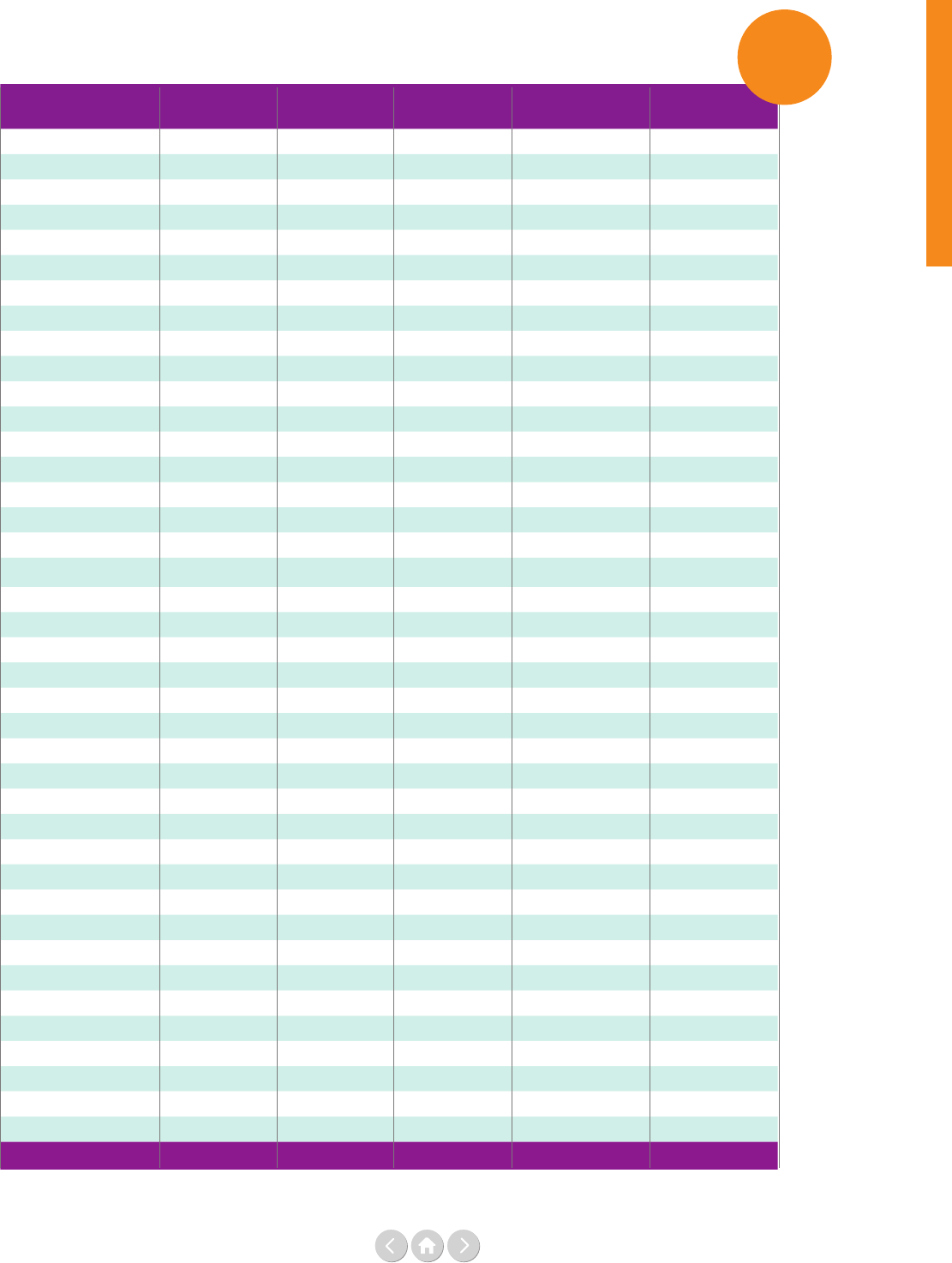

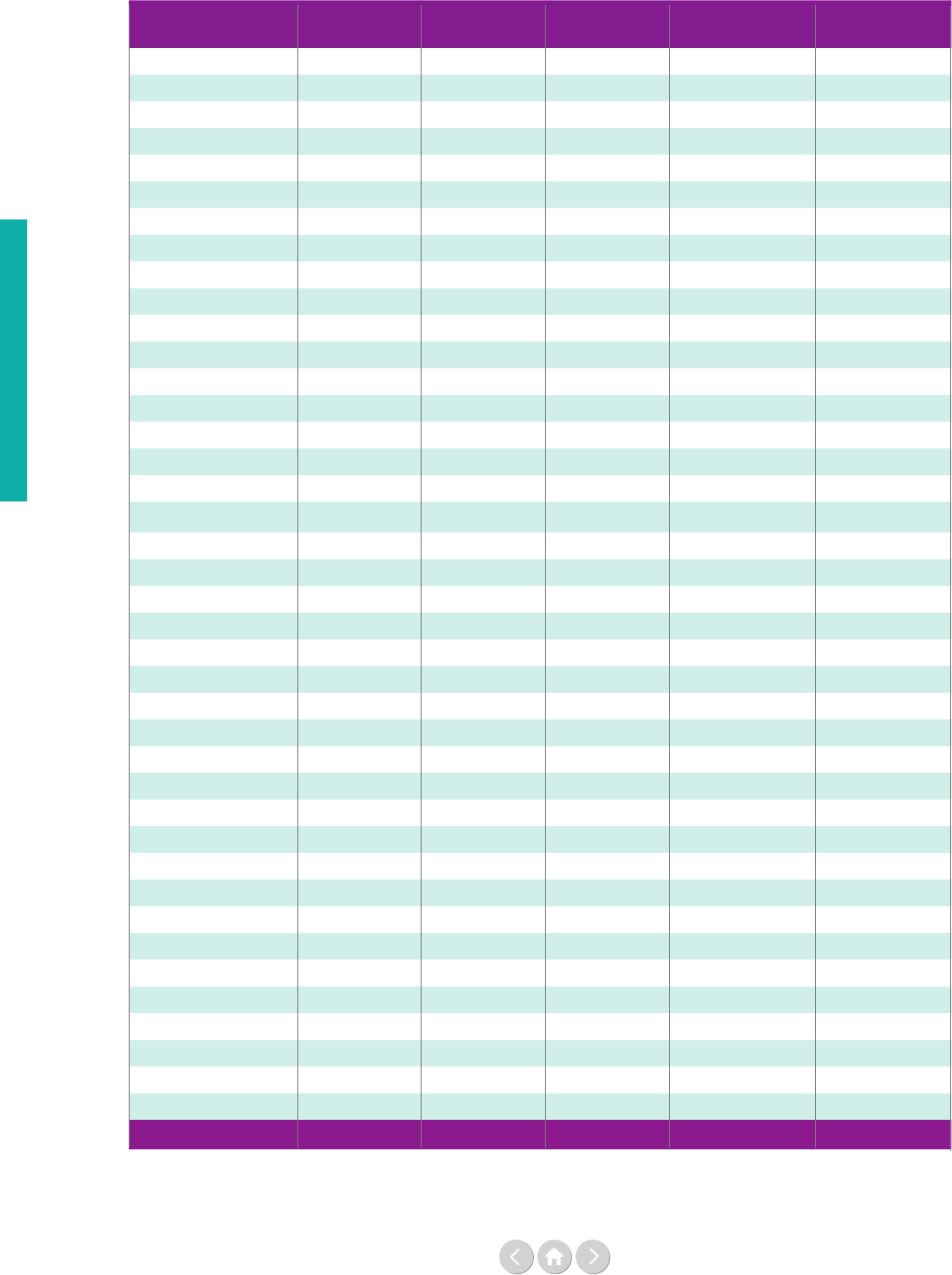

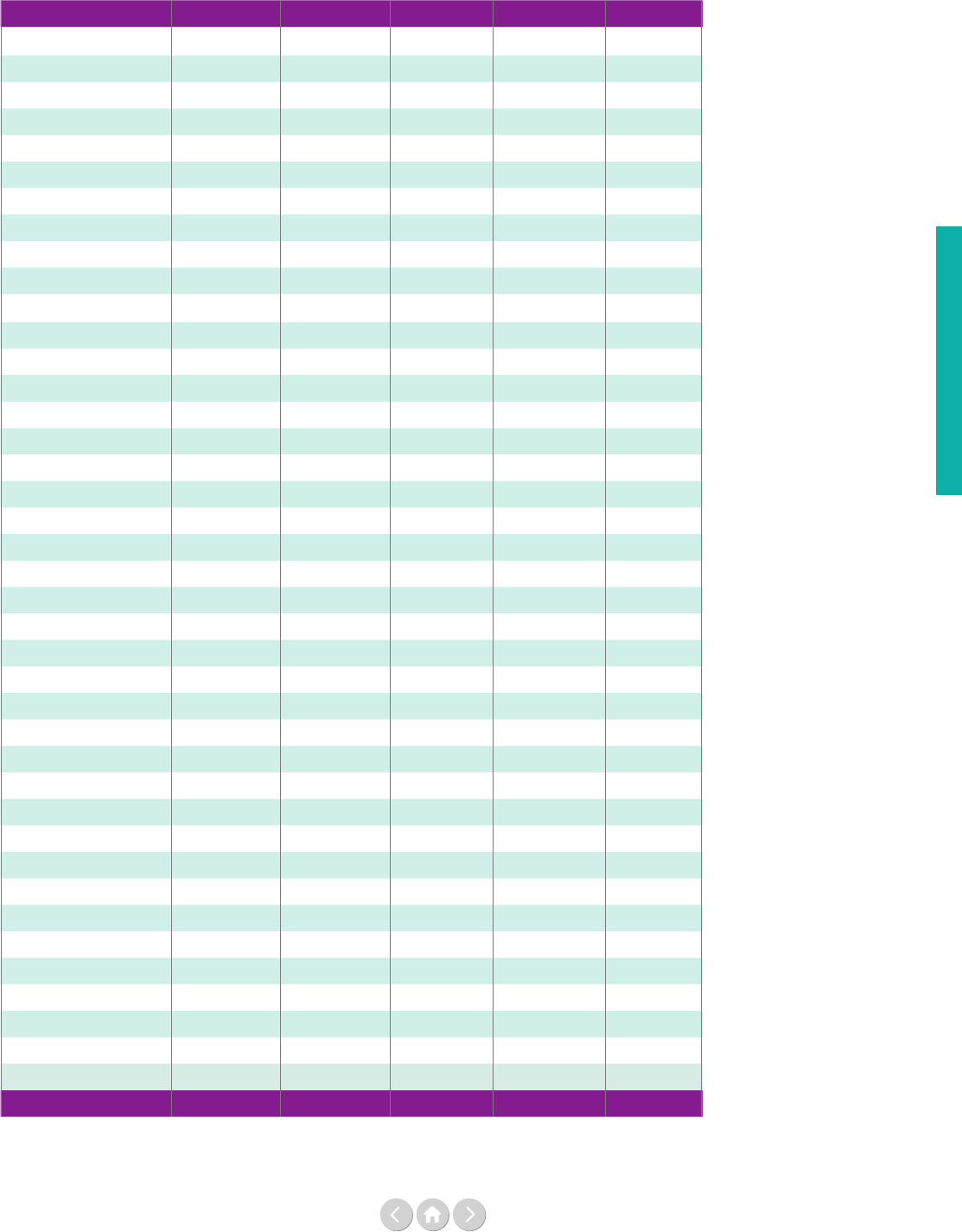

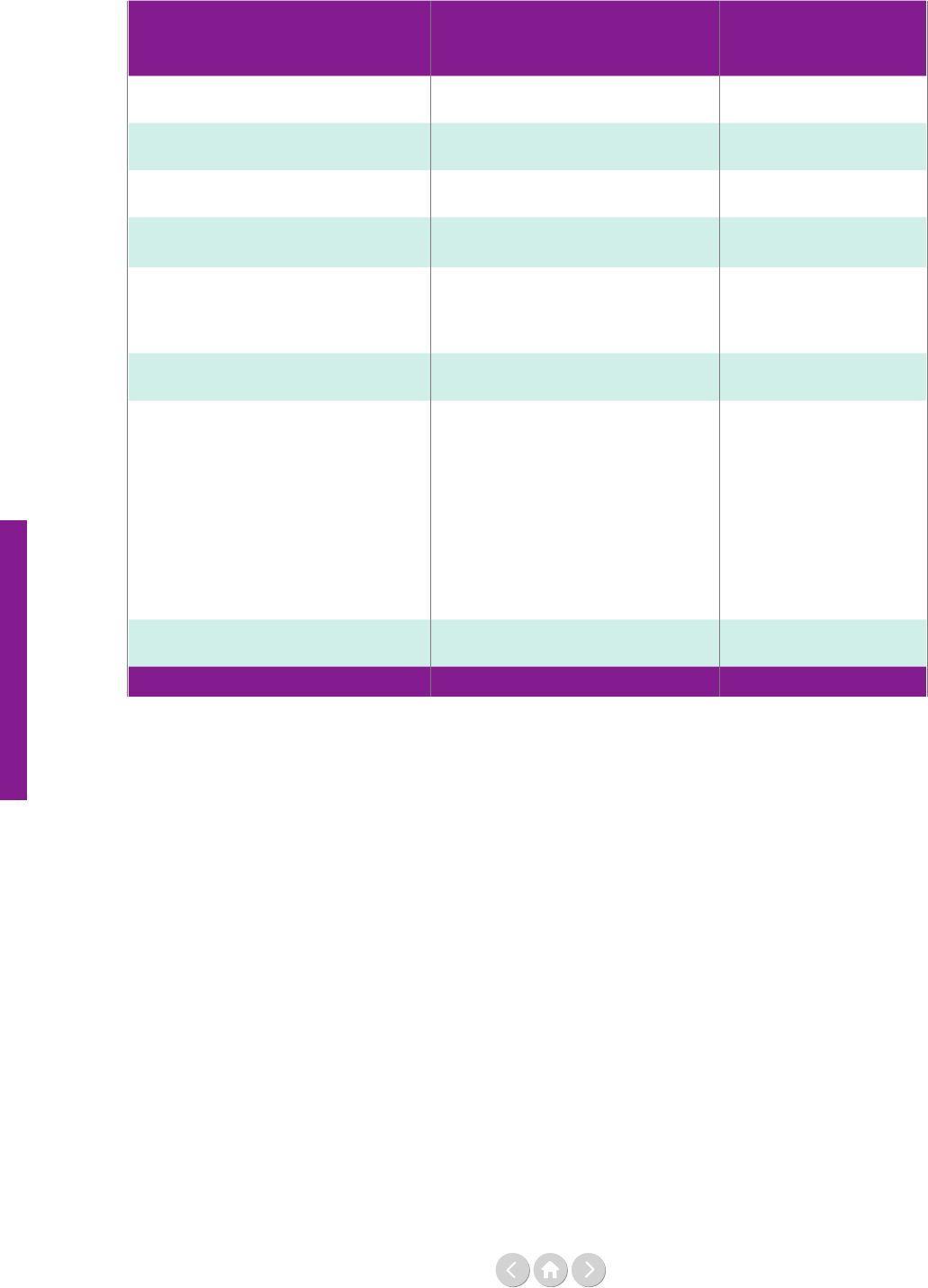

Total revenue of the UN system by entity and by financing instrument, 2017 (US$ million)

(Table 2a from Part One, Chapter One):

Source: see page 30

Entity Assessed

Voluntary

core

Earmarked

Fees and

other revenues

Total

revenue 2017

UN Secretariat

2,578 2,279 623 5,480

CTBTO

119 7 2 128

DPKO

7,853 343 79 8,276

FAO

474 751 39 1,264

IAEA

434 260 8 702

ICAO

80 114 22 216

ICC

167 2 0 170

IFAD

306 104 9 419

ILO

370 293 21 683

IMO

41 7 19 67

IOM

49 15 1,450 100 1,615

ITC

35 29 62 1 127

ITU

125 1 10 47 183

PAHO

102 614 716 1,433

UNAIDS

173 52 8 233

UNCDF

10 47 3 60

UNDP

647 4,245 344 5,236

UNEP

199 443 25 668

UNESCO

316 261 71 648

UNFCCC

31 2 38 15 86

UNFPA

350 718 93 1,160

UN-HABITAT

14 3 142 11 169

UNHCR

48 703 3,445 31 4,227

UNICEF

1,278 5,153 146 6,577

UNIDO

80 256 3 339

UNITAR

0 32 0 33

UNODC

31 4 342 15 391

UNOPS

834 834

UNRISD

2 0 2

UNRWA

625 559 55 1,239

UNSSC

4 7 0 11

UNU

49 58 107

UN Women

8 146 214 10 379

UNWTO

16 3 5 24

UPU

37 17 16 69

WFP

391 5,609 431 6,431

WHO

457 81 2,058 179 2,775

WIPO

18 1 11 392 423

WMO

70 5 17 2 94

WTO

200 21 2 224

Total 13,953 4,776 30,035 4,435 53,200

Table

2a

12

Executive summary

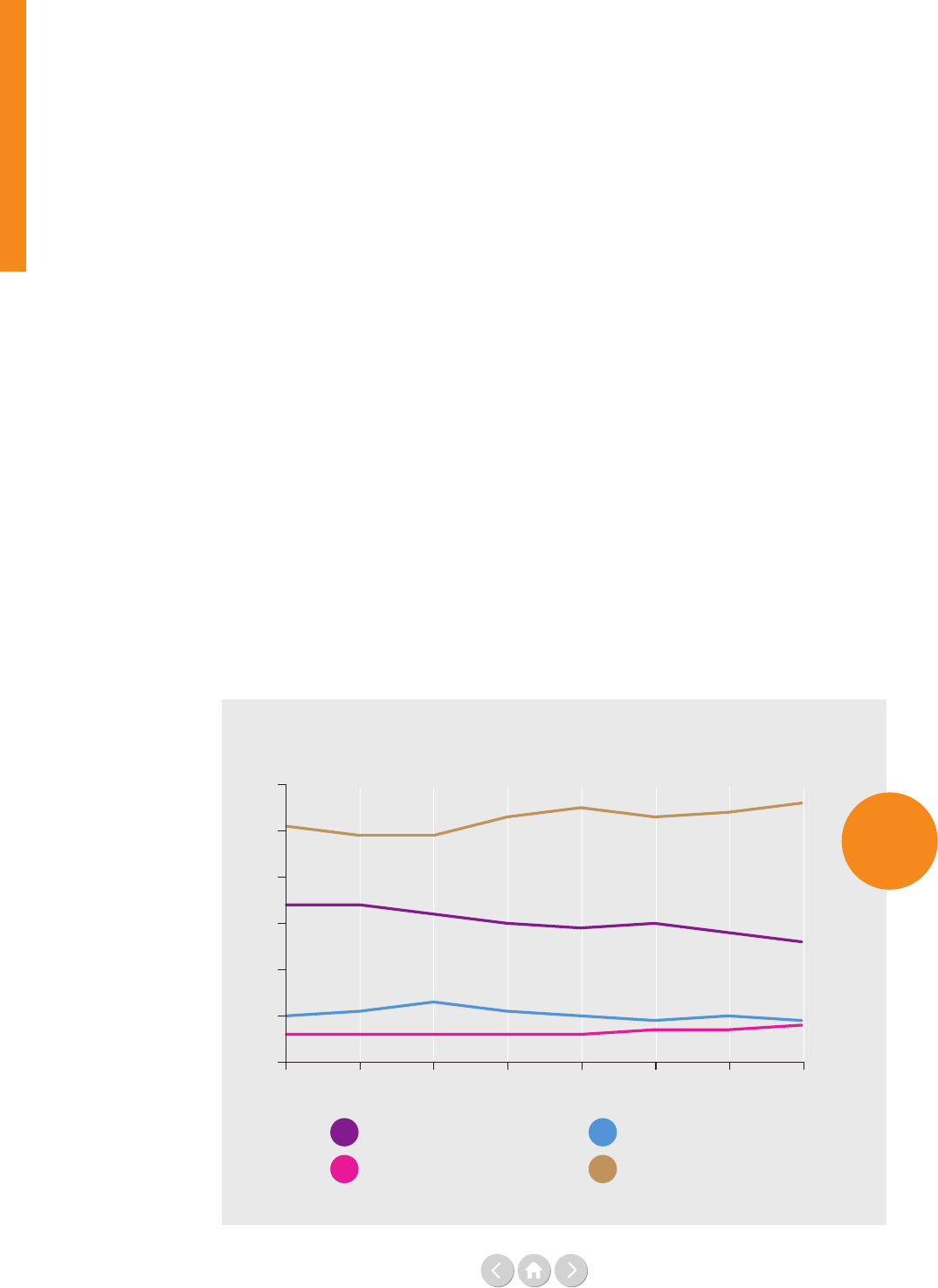

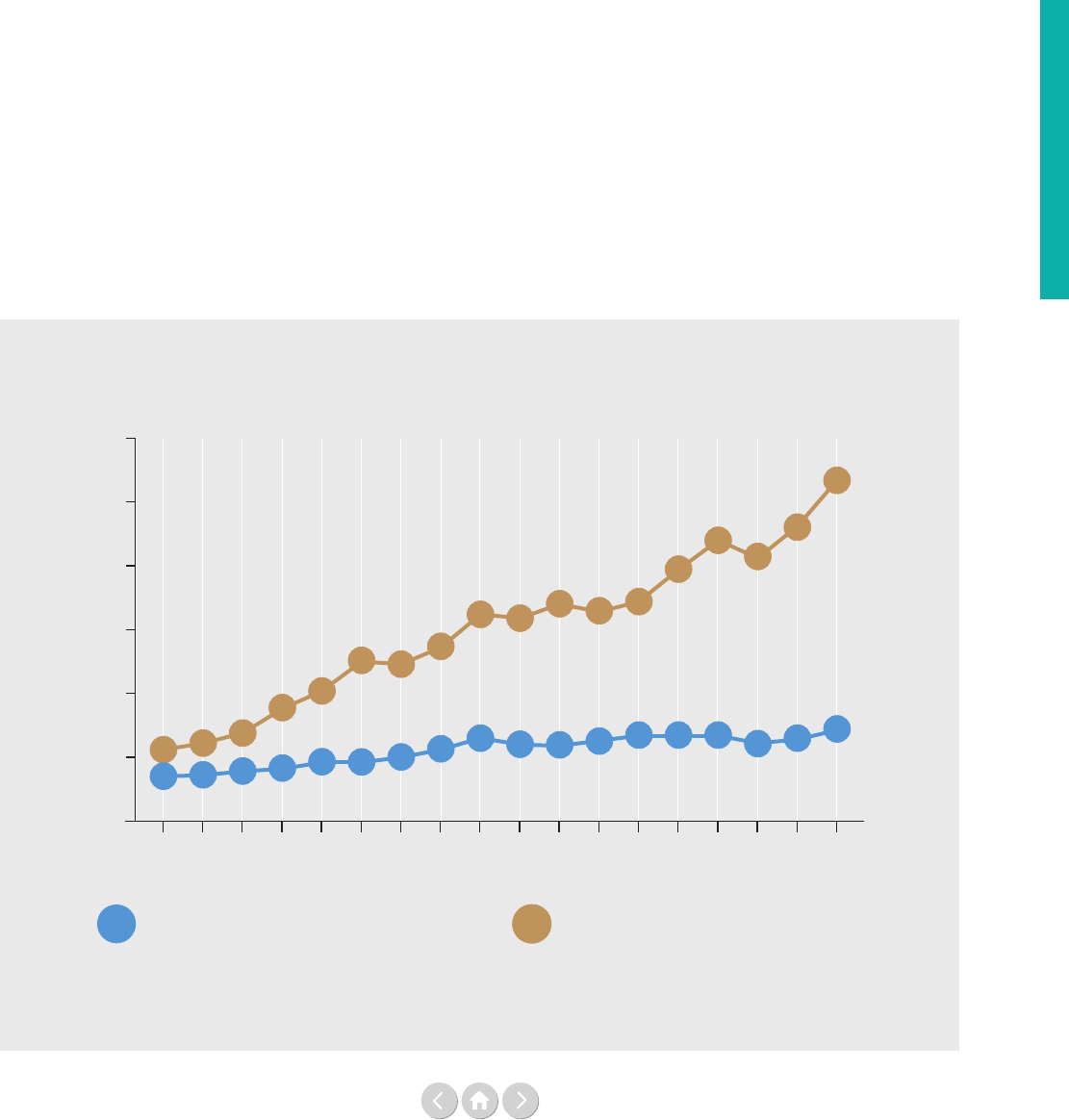

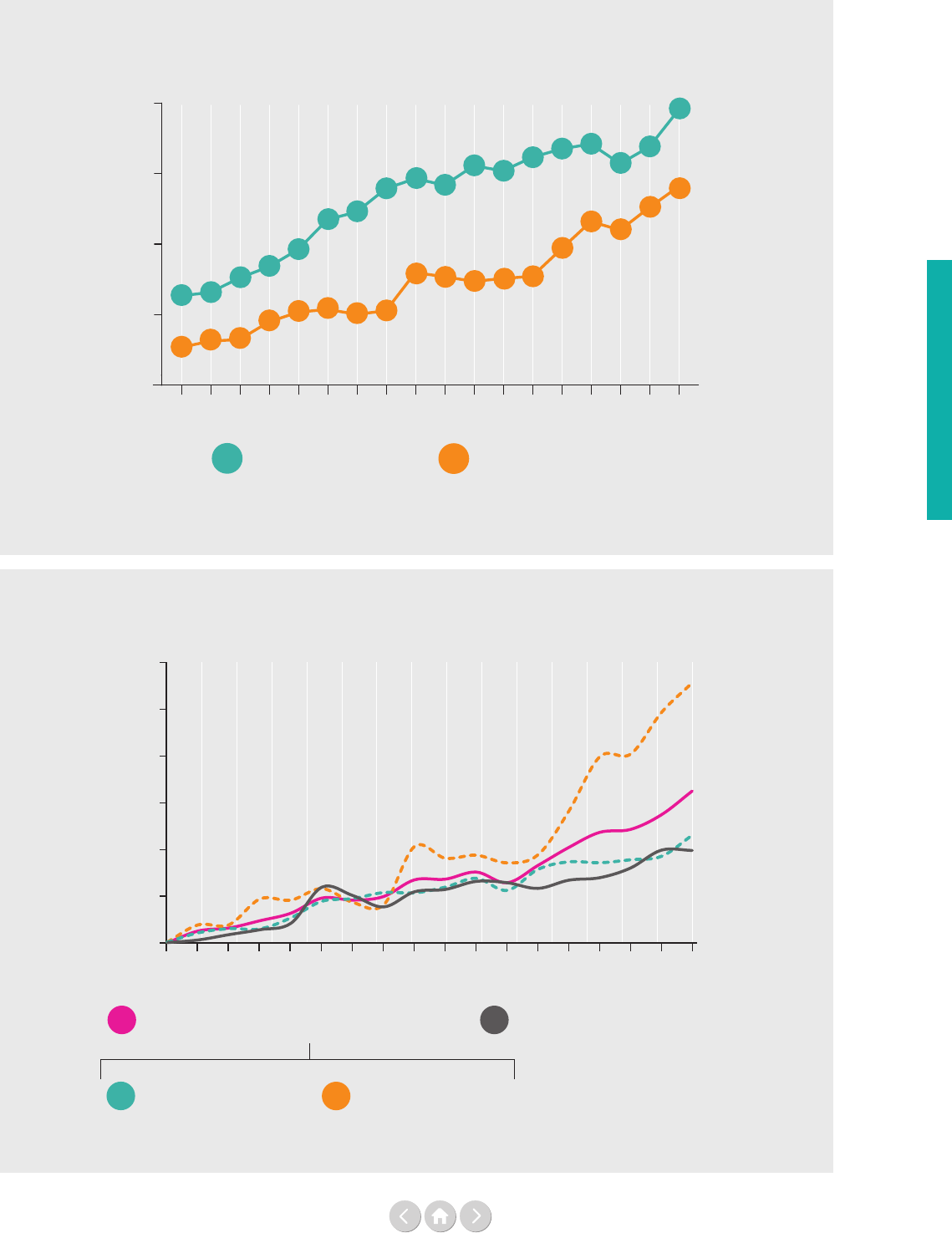

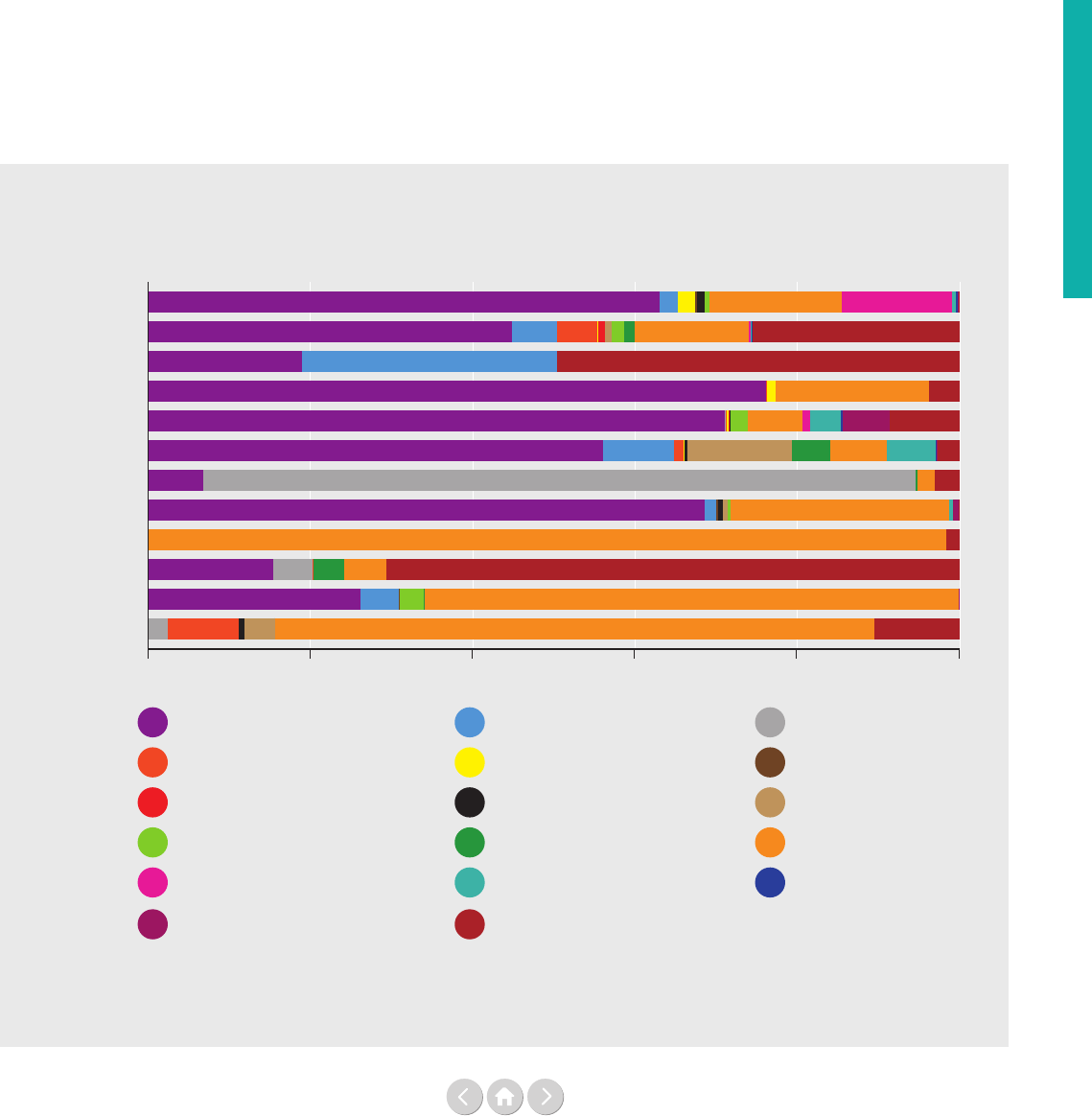

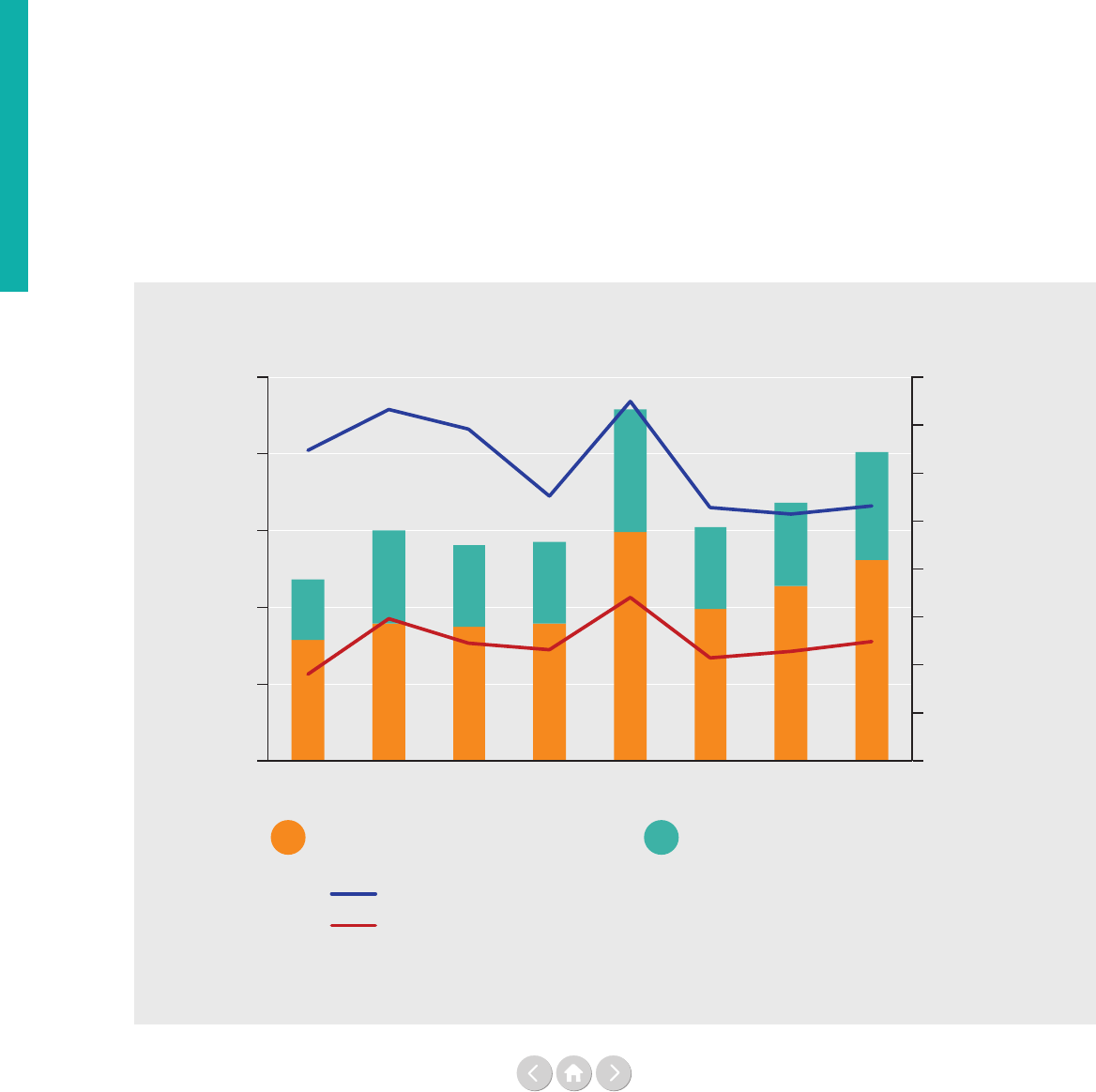

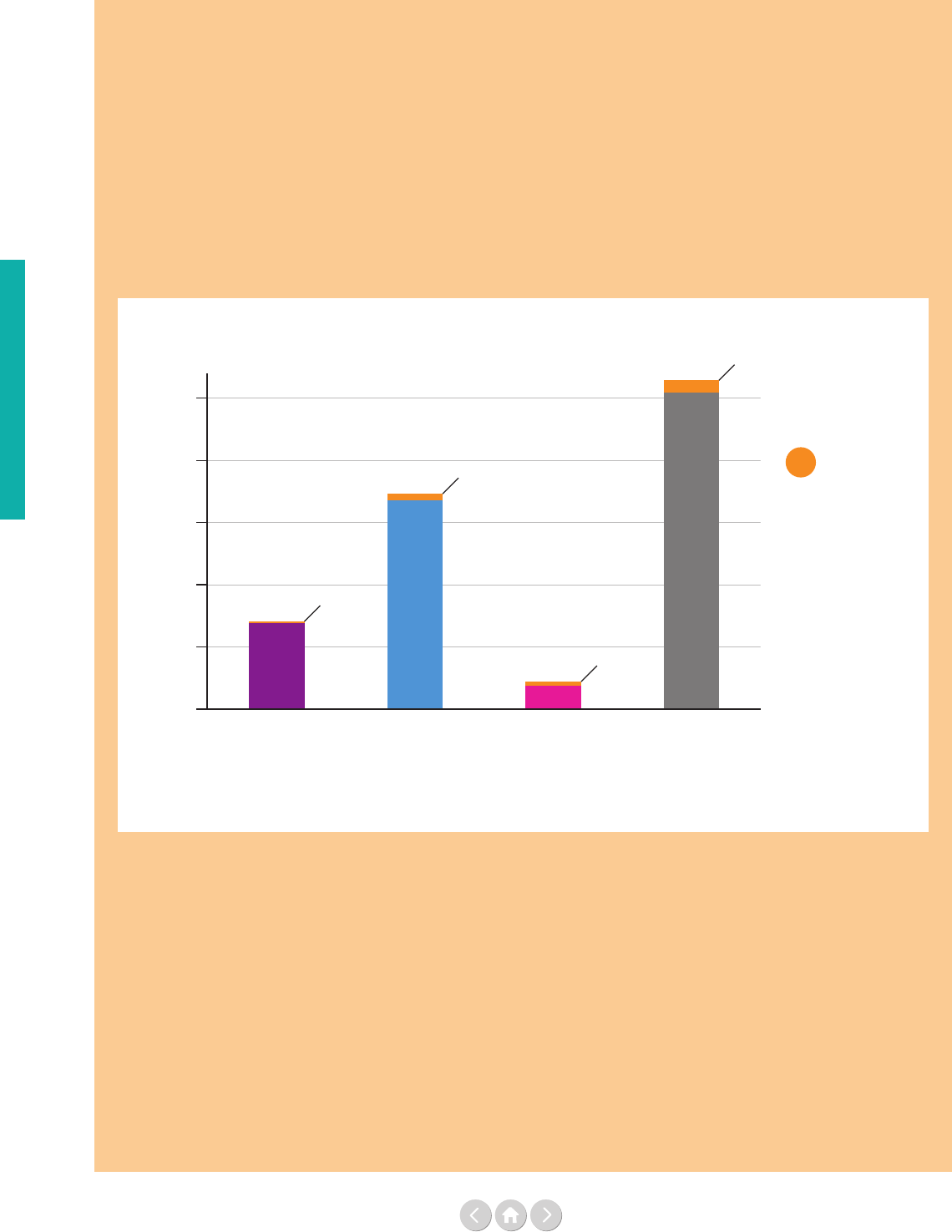

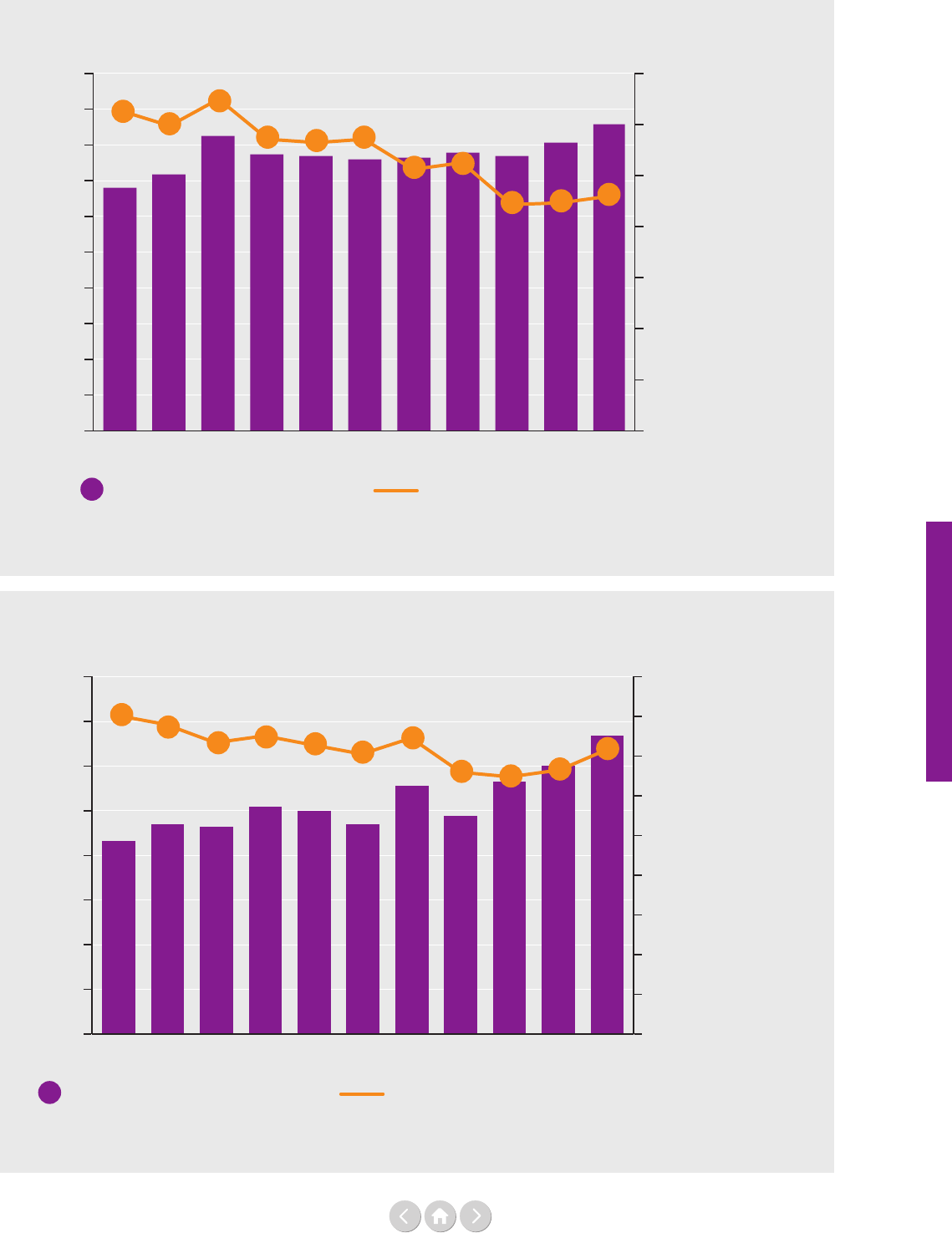

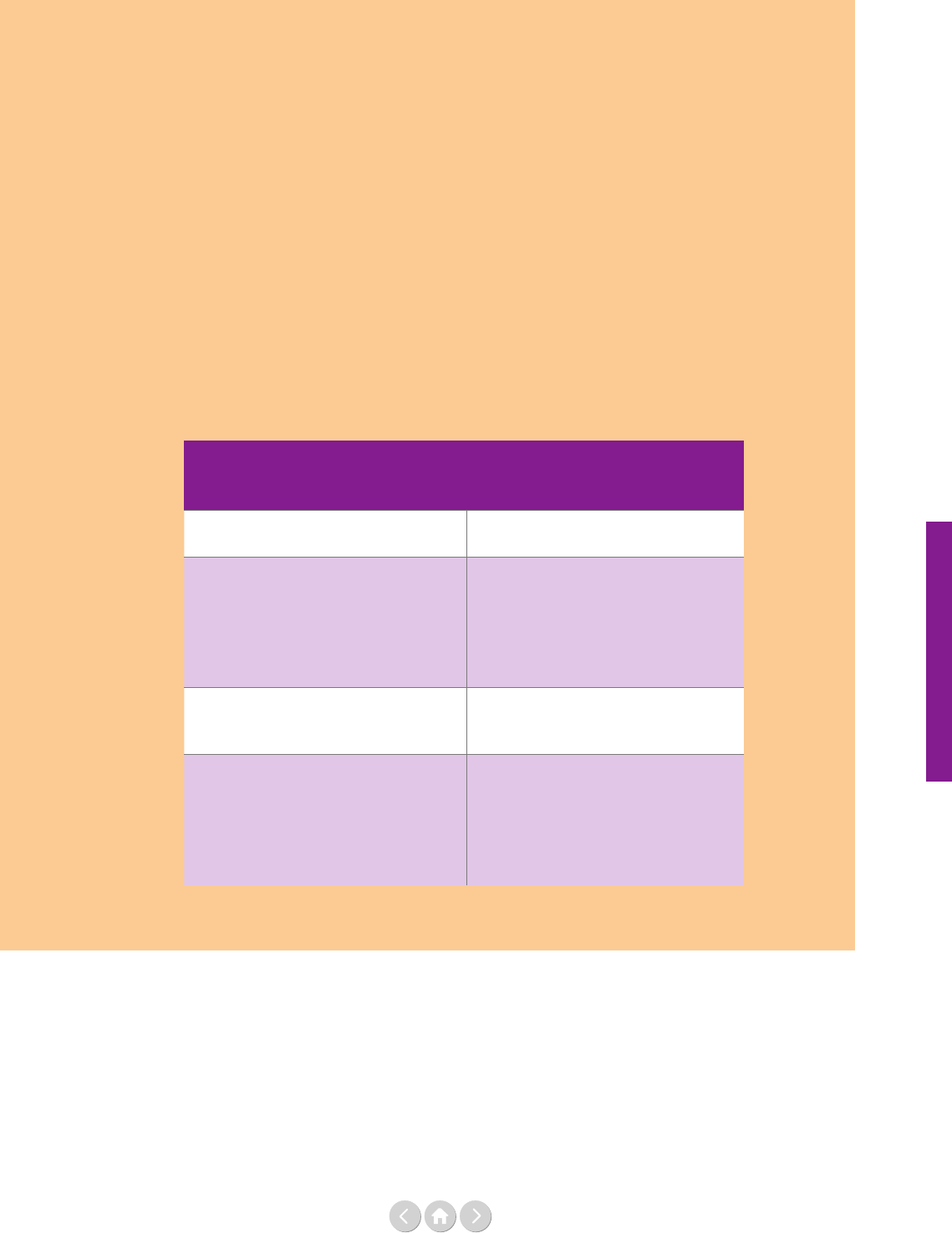

Distribution of total UN system revenue, by financing instrument, 2010–2017

(Figure 2 from Part One, Chapter One):

Source: see page 29

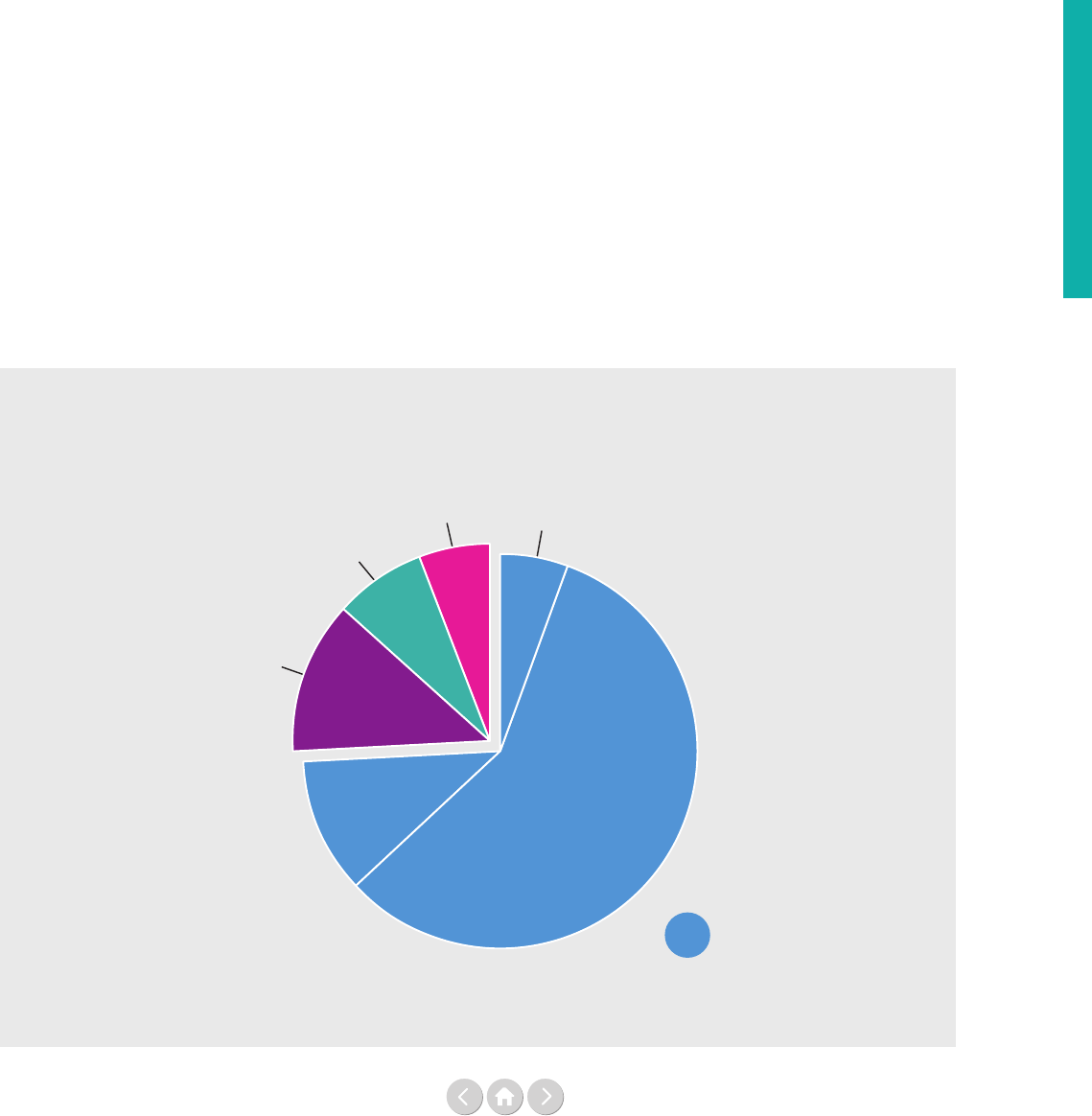

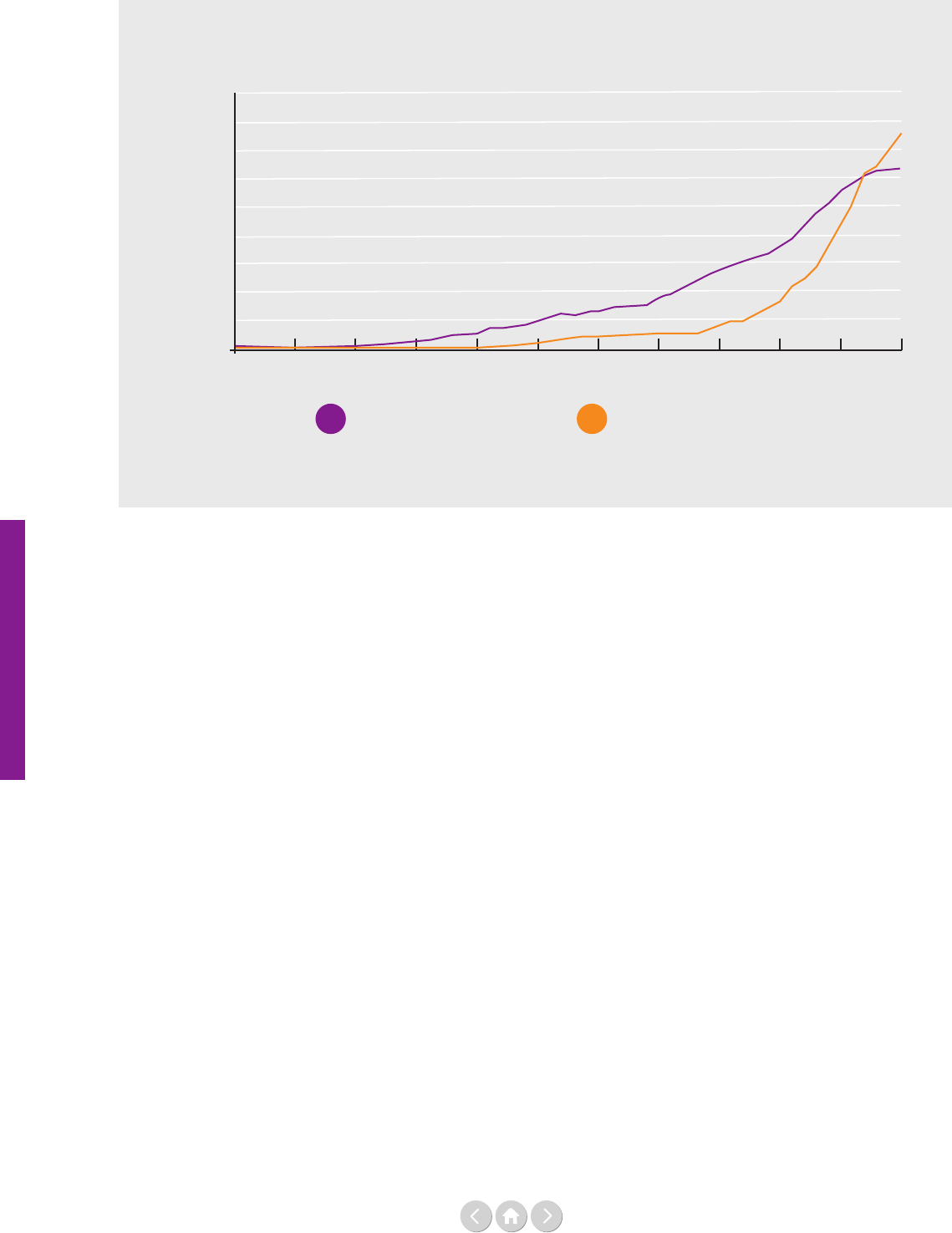

How these UN entities are nanced inuences how they

operate, and in 2017 more than half of all UN revenue

was earmarked to a certain degree (57%). This is a three

percentage point increase since the previous year and is

part of a long-term trend in UN nancing, which has

seen a relative decline of the more exible contributions

(assessed and voluntary core) and a relative shift towards

the more constrained earmarked contributions. In 2017,

voluntary core contributions decreased by one percent-

age point to 9%, which almost equalled the 8% that

came from ‘fees and other revenues’ (Figure 2).

Meanwhile, assessed contributions amounted to 26%.

The next question is what part and which revenue

streams of the UN are growing? The UN’s overall revenue

growth has been concentrated in UN Operational

Activities for Development (UN-OAD), which grew

from US$ 29.5 billion in 2016 to US$ 33.6 billion in

2017 (UN non-OAD activities decreased slightly from

US$ 19.8 to 19.6 billion). It is, however, specically the

earmarked resources for UN-OAD that have increased

(from US$ 23.1 to 26.7 billion). A closer look at the

levels of earmarked contributions to each UN entity

(as well as assessed contributions) is detailed in the full

report, and it shows, for example, that in 2017 for seven

UN entities, over 80% of their funding was earmarked.

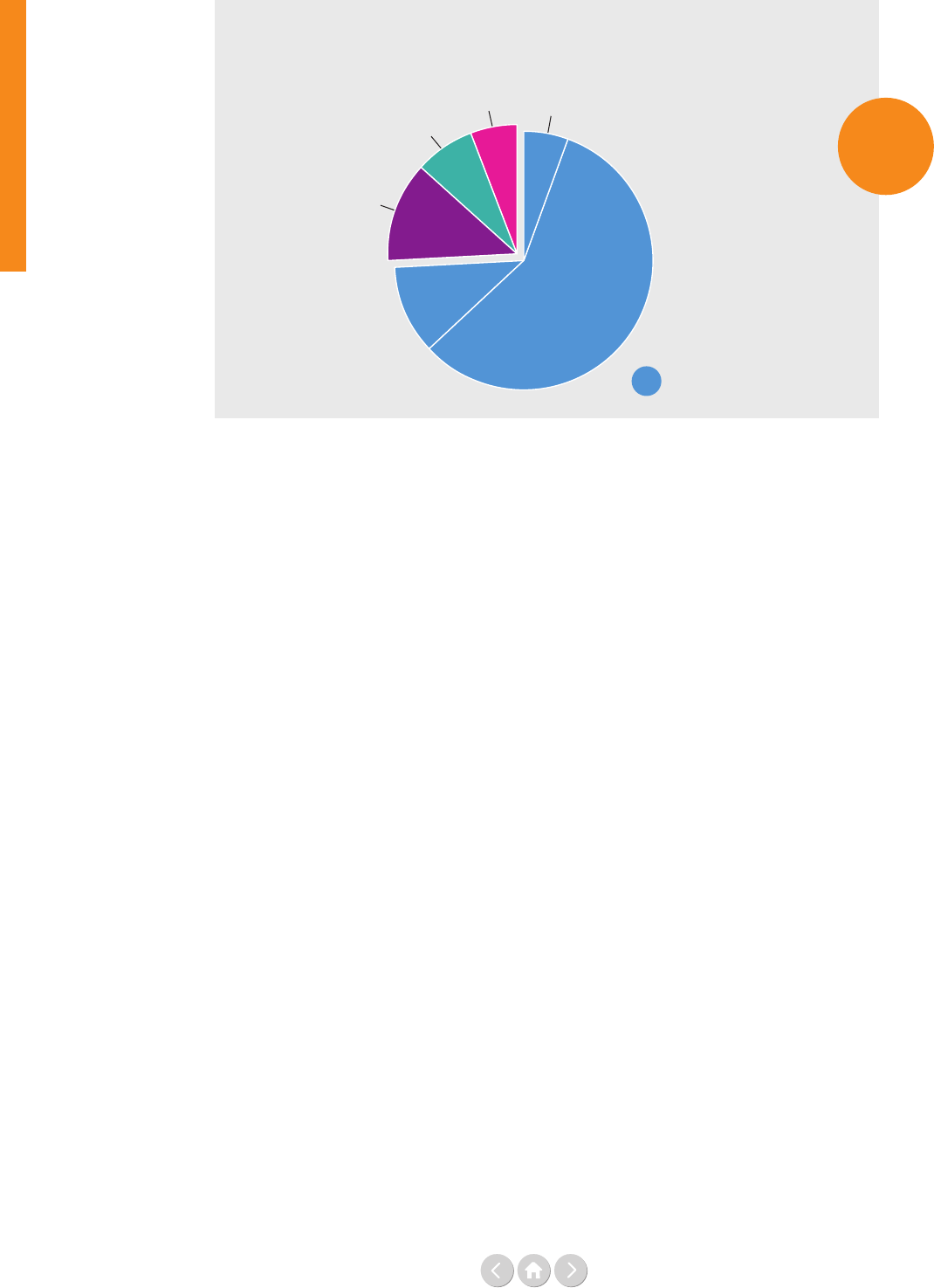

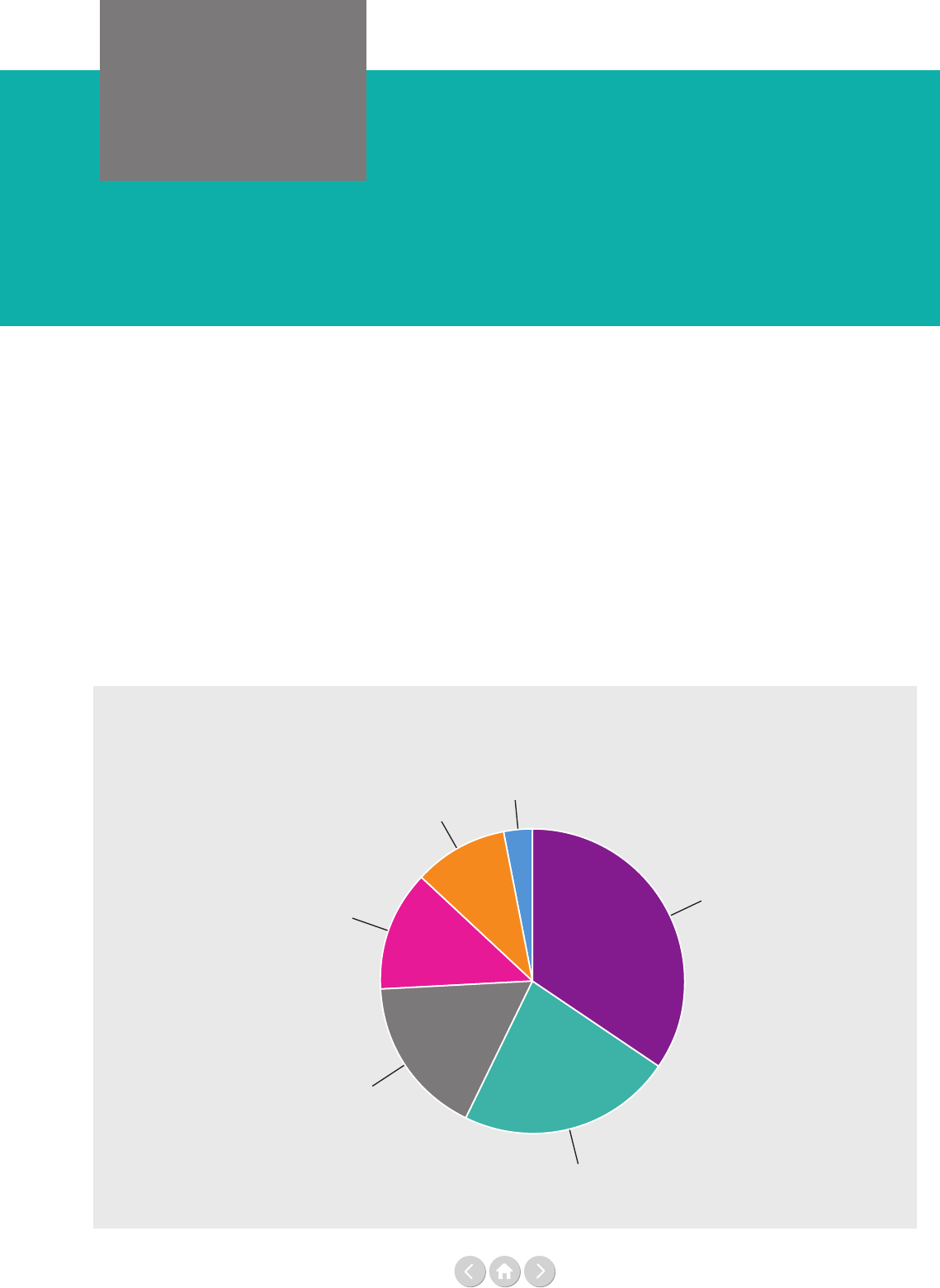

Having looked at the revenue streams into the dierent

UN funding instruments, the report also examines what

is being funded in the UN. Figure 5 shows 32% of the

funding in 2017 went to humanitarian assistance, which

is a growth of four percentage points compared to the

previous year. The relative share of funding for develop-

ment and peacekeeping has remained stable, while the

category of global norms, standards, policy and advocacy

has decreased by four percentage points compared to

2016. A note of caution before drawing too many

conclusions: the decrease in the category of global norms

is more linked to denitional and methodological issues

than with the UN investing fewer resources in its

normative mandates.

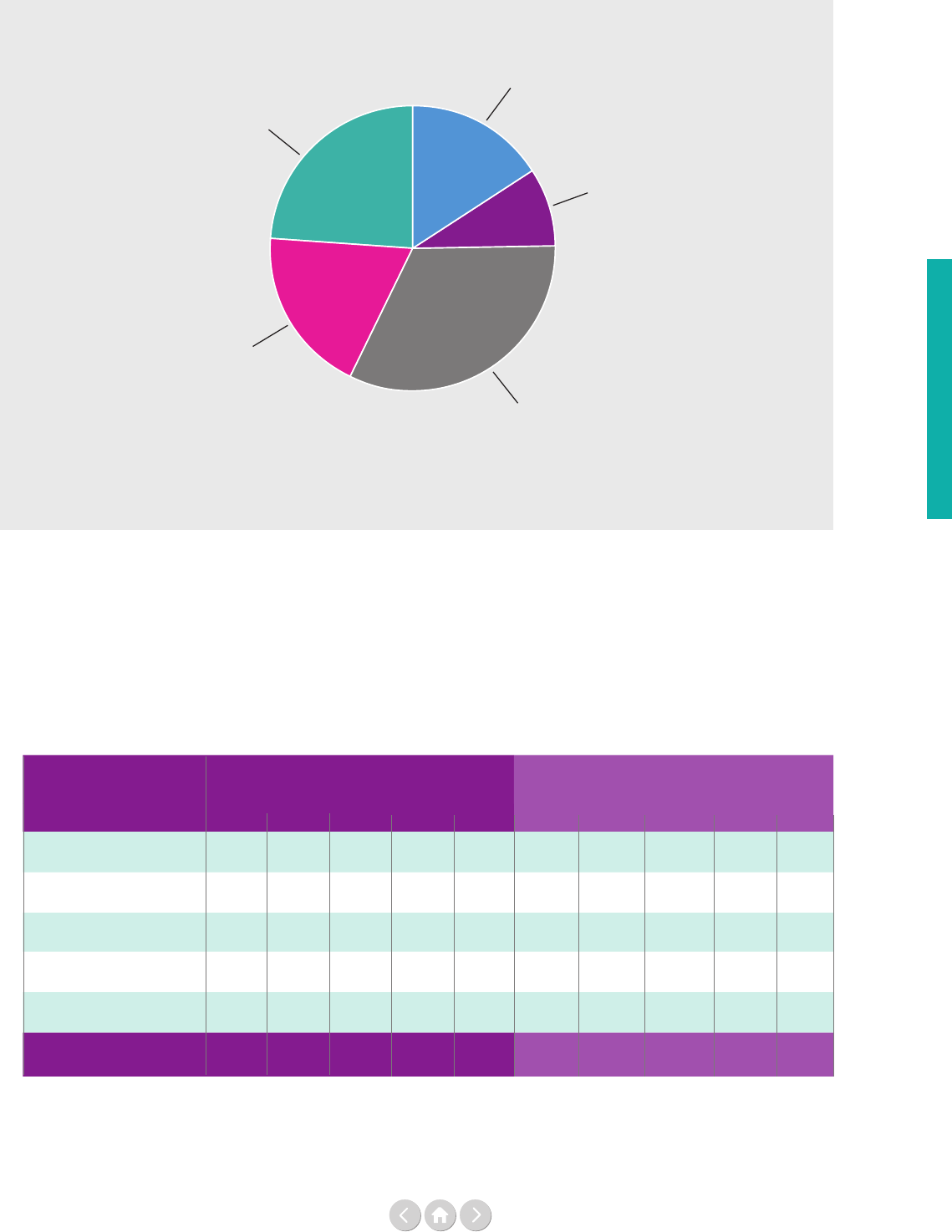

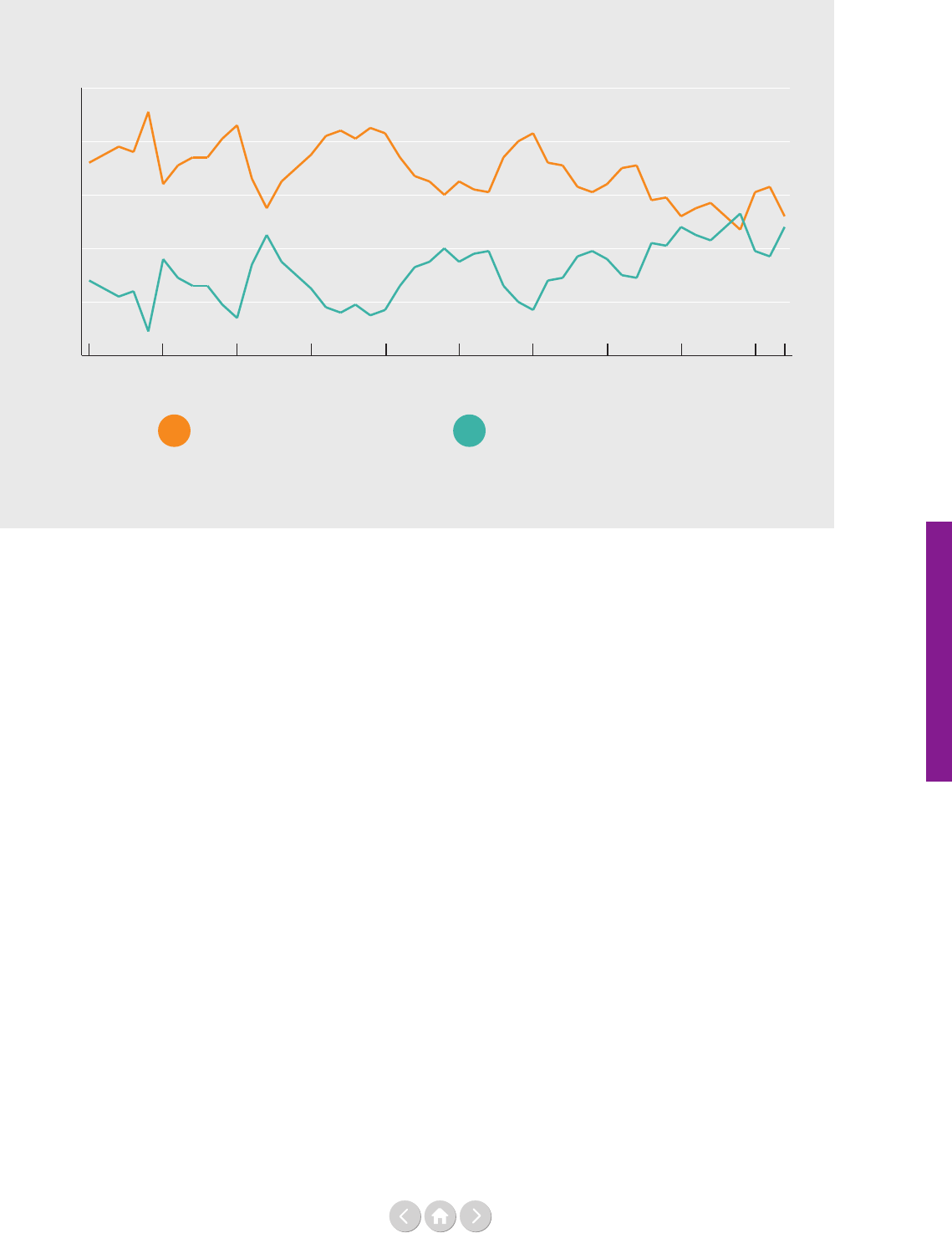

If we now turn to how the UN ts into the funding

picture of the broader multilateral system we see in

Figure 10 how important the UN is as a multilateral

channel. Indeed, the UN remains the largest channel of

multilateral assistance from countries part of the

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development’s Development Assistance Committee

(OECD-DAC) with US$ 20.9 billion in contributions

in 2017, which represents 33% of the total (see Figure 9

on page 39).

In Figure 10 we also see major funding dierences and

trends between the multilateral institutions. Higher levels

of earmarking compared to core funding distinguish the

UN system from other multilateral institutions. More-

over, the share of earmarking has increased substantially

in the UN in recent years. In 2017, of the US$ 20.9

billion of multilateral aid channelled through the UN

development system, 71% was earmarked, against 64% of

the US$ 16.6 billion in 2013.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

57%

26%

9%

8%

Assessed contributions

Fees and other revenues

Voluntary core contributions

Earmarked contributions

2016

2014

2012

2017

2015

2013

2011

2010

Figure

2

13

Executive summary

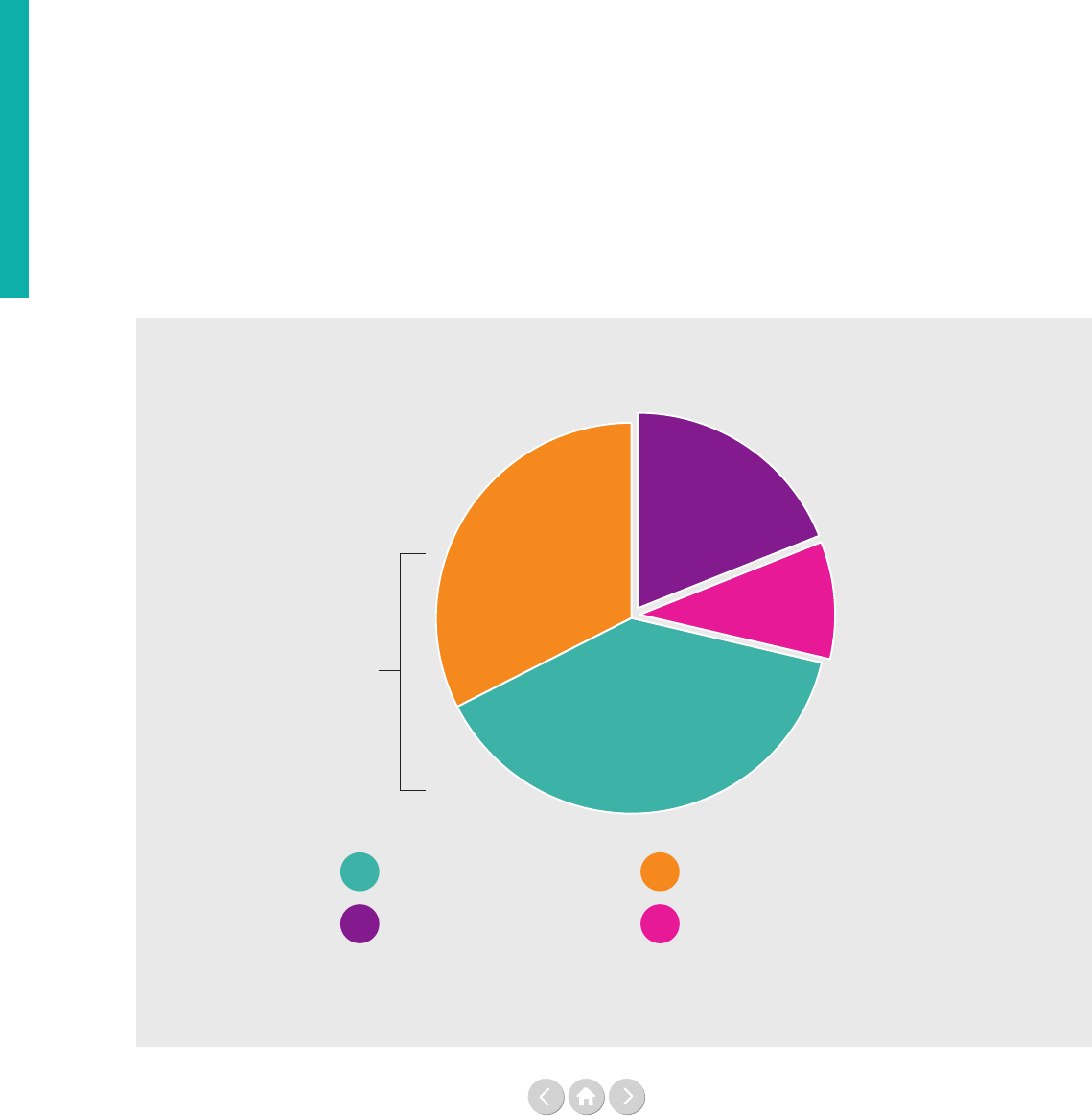

Executive summary

Funding of UN system-wide activities, 2017

(Figure 5 from Part One, Chapter One):

Source: see page 36

Channels of total multilateral assistance from OECD-DAC countries,

core and earmarked, 2013 and 2017 (Figure 10 from Part One, Chapter One):

Source: see page 40

Operational activities

for development 71%

19%

32%

39%

10%

Development assistance Humanitarian assistance

Peacekeeping Global norms, standards,

policy and advocacy

0 5 10 15 20 25

Other multilateral institutions

Regional development banks

UN development system

World Bank Group and

International Monetary Fund

European Union institutions

15.0

11.2

12.1

12.0

4.2

5.5

9.0

10.4

16.6

20.9

US$ billion

Earmarked

Core

2013

2017

2013

2017

2013

2017

2013

2017

2013

2017

A more detailed ve-year multilateral funding trend can

be seen in Table 5 in Chapter One of the full report.

This data does, however, not capture the whole picture

with regards to trends in Ocial Development

Assistance (ODA) funding, since contributions from

OECD-DAC members to multilateral organisations

represented only around 41% of total ODA in 2016.

Figure

5

Figure

10

14

Executive summary

Funding sources for UN operational activities, 2017

(Figure 11 from Part One, Chapter One):

Source: see page 41

Inter-agency pooled funds

6%

Vertical funds

6%

European Union institutions

7%

NGO, private and others

13%

non OECD-DAC

11%

OECD-DAC

57%

Governments 74%

group of countries, which was 7% of the total of contri-

butions to UN operational activities. Compared to 2016,

China has increased its funding the most in nominal terms

and of the same group, Qatar increased its funding most

in relative terms. Local resources, which are contributions

from programme countries in support of their own

development framework, are depicted separately. They

have only been added after the top 12 non OECD-DAC

contributors were identied.

In this year's report we bring back our 2017 analysis of

levels of funding that individual UN Member States are

contributing to six UN entities, United Nations Develop-

ment Programme (UNDP), United Nations High

Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UNICEF,

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine

Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), World Food

Programme (WFP) and WHO. It specically shows how

much the top ten OECD-DAC and top ten non OECD-

DAC countries contribute to each of the entities above in

core and earmarked funding. A visual comparison can be

found on pages 50-51 (Figures 29-32). While all ten of

the OECD-DAC countries contribute core resources to

all six entities, the total portfolio of core contributions is

not dominated by one single entity.

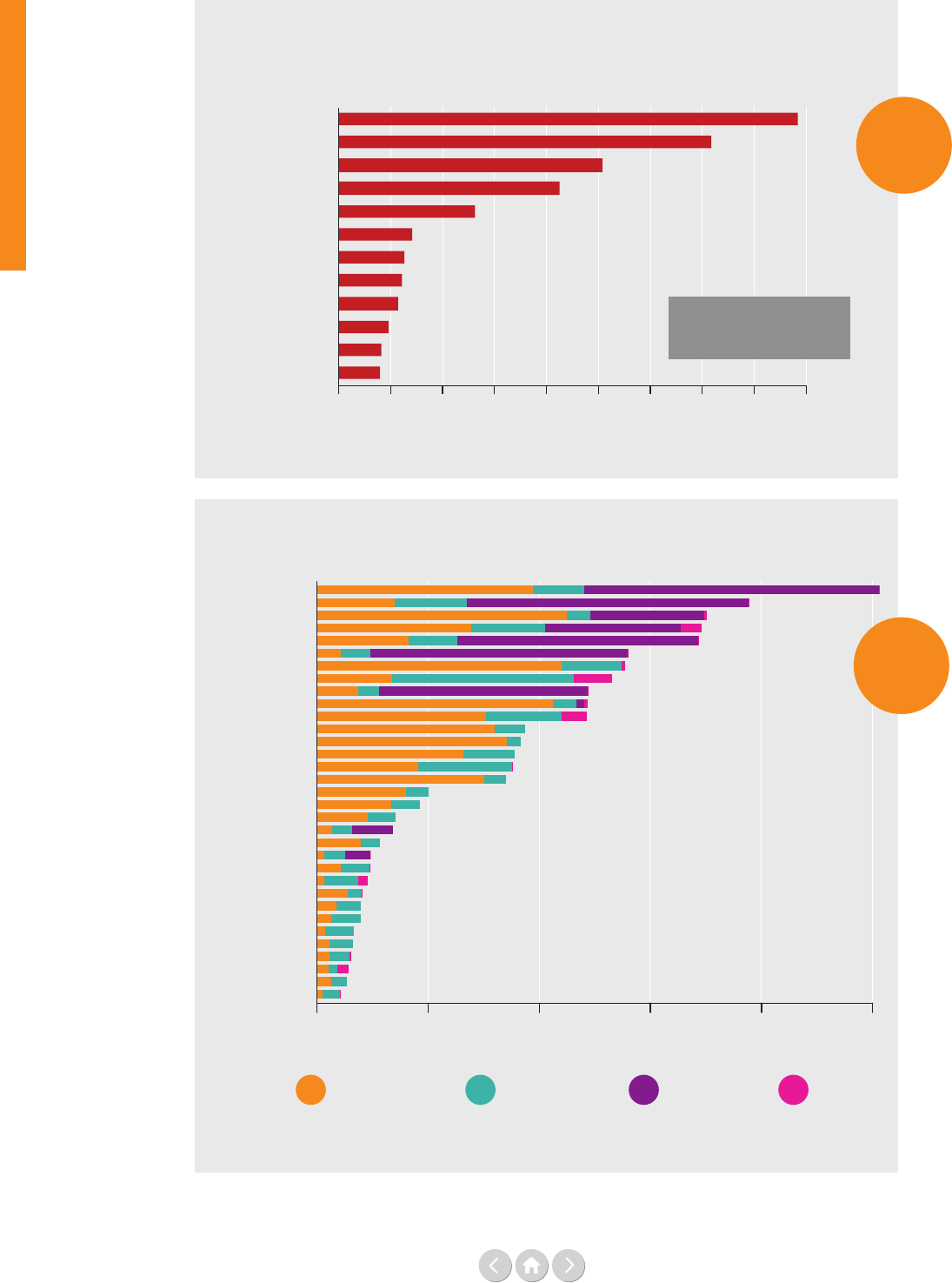

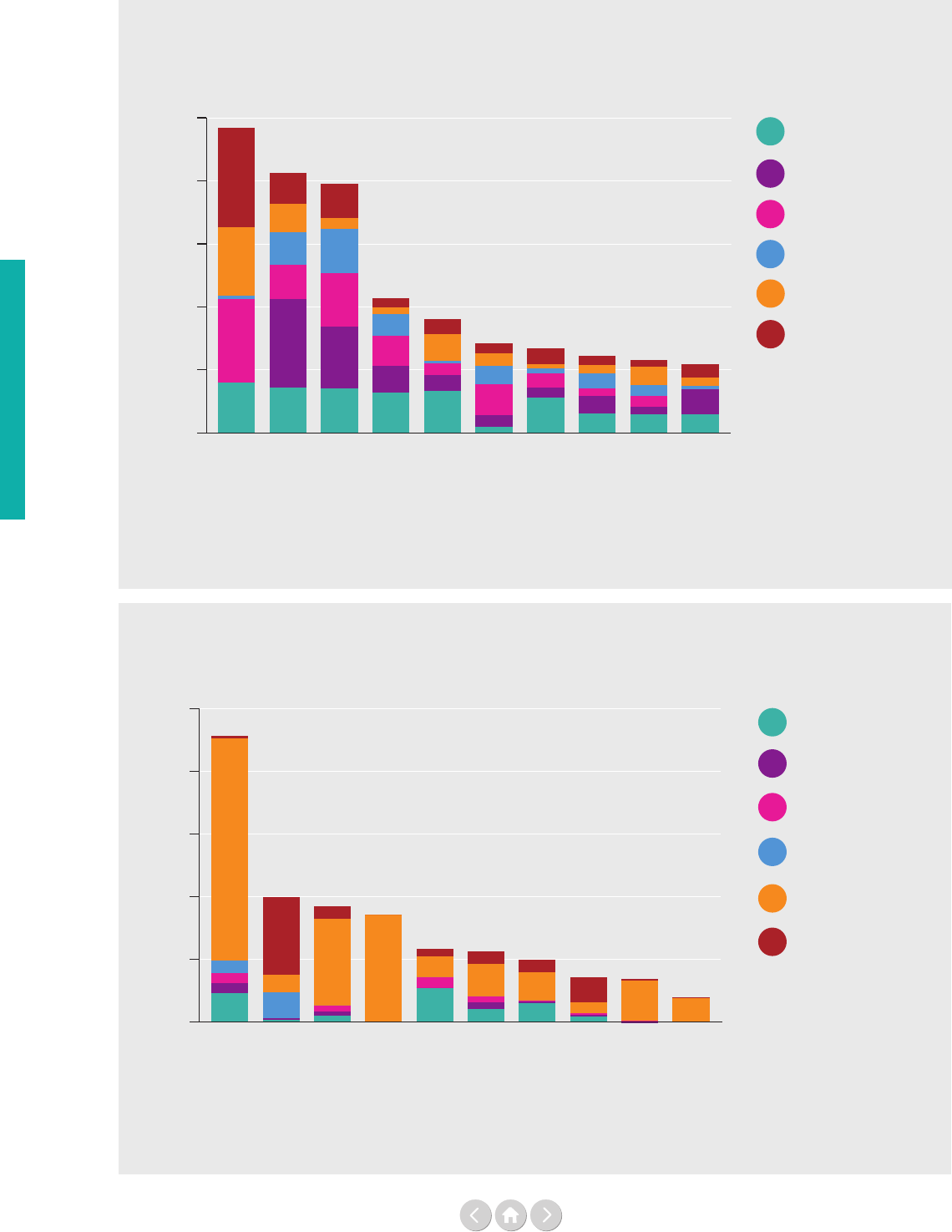

Finally, this chapter also takes a closer look at the use and

scale of UN inter-agency pooled funds. In Figure 34 (page

16) we see the top 12 contributors to these funds and the

share of earmarked resources they channel through pooled

funds. It points to the need to increase the funding to this

type of nancial instrument if the target set in the recent

Funding Compact is to be met (doubling of contributions

to UN inter-agency pooled funds by 2023).

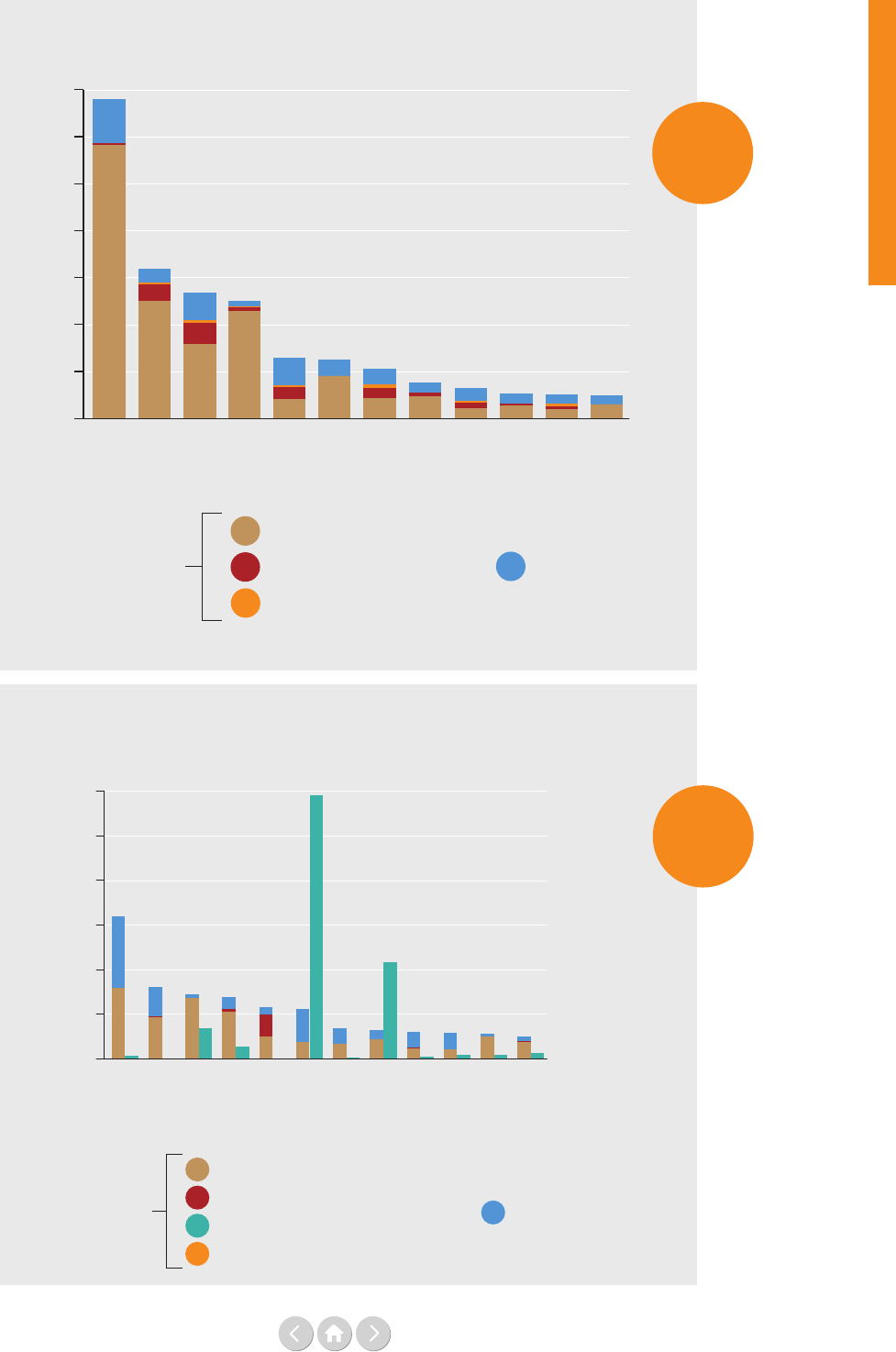

So, knowing that OECD-DAC countries channel a

signicant part of their ODA funding into the UN, how

much of the overall UN funding pie is that? Who are the

other funders of the UN? As we can see in Figure 11,

governments constituted 74% of the direct funding to

the UNDS with 57% coming from OECD-DAC

countries and 11% from non OECD-DAC countries.

Indirectly governments also funded the UNDS via

eg the European Union (EU) institutions and in-part via

UN pooled and vertical funds. An equal share of 6% of

total funding to the UNDS was channeled through UN

inter-agency pooled funds and vertical funds.

While non-state contributions are growing signicantly as

sources of revenue for the UN (from 9% in 2016 to 13%

in 2017), they remain a relatively small source of revenue

for most UN entities (a visual breakdown of the non-state

funding for six UN entities is provided in the report).

In fact, the majority of contributions to UN operational

activities come from a small group of Member States.

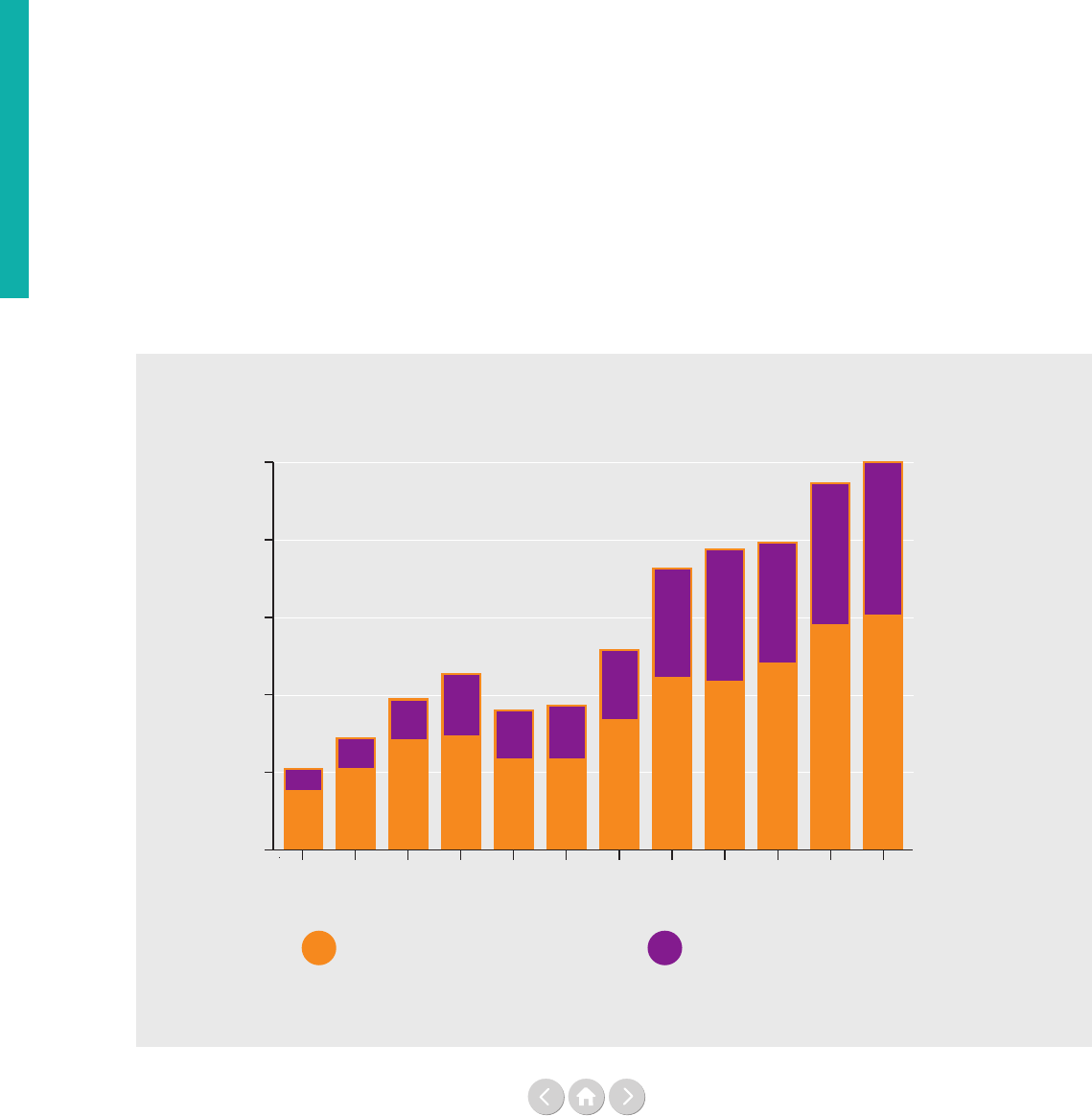

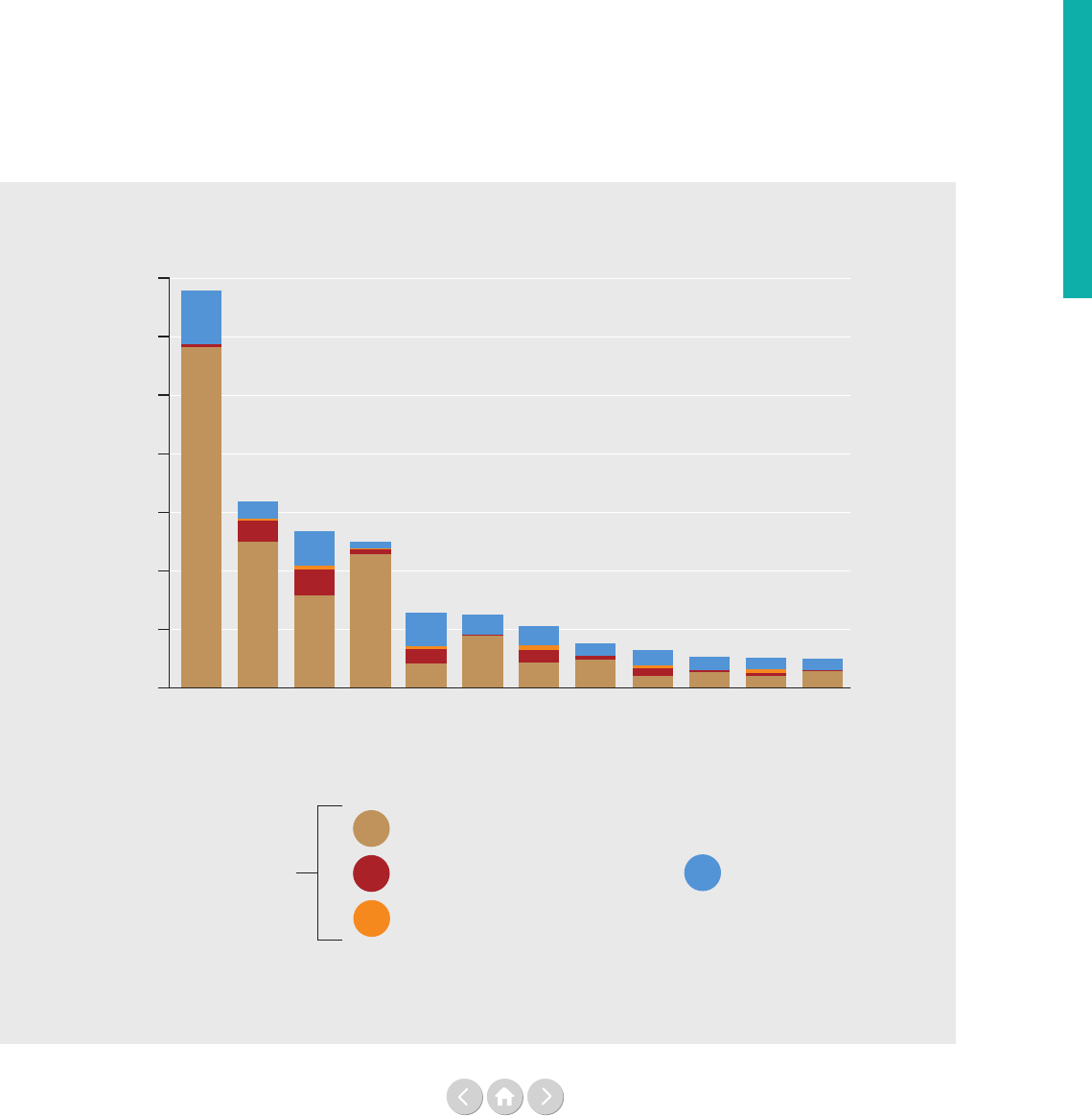

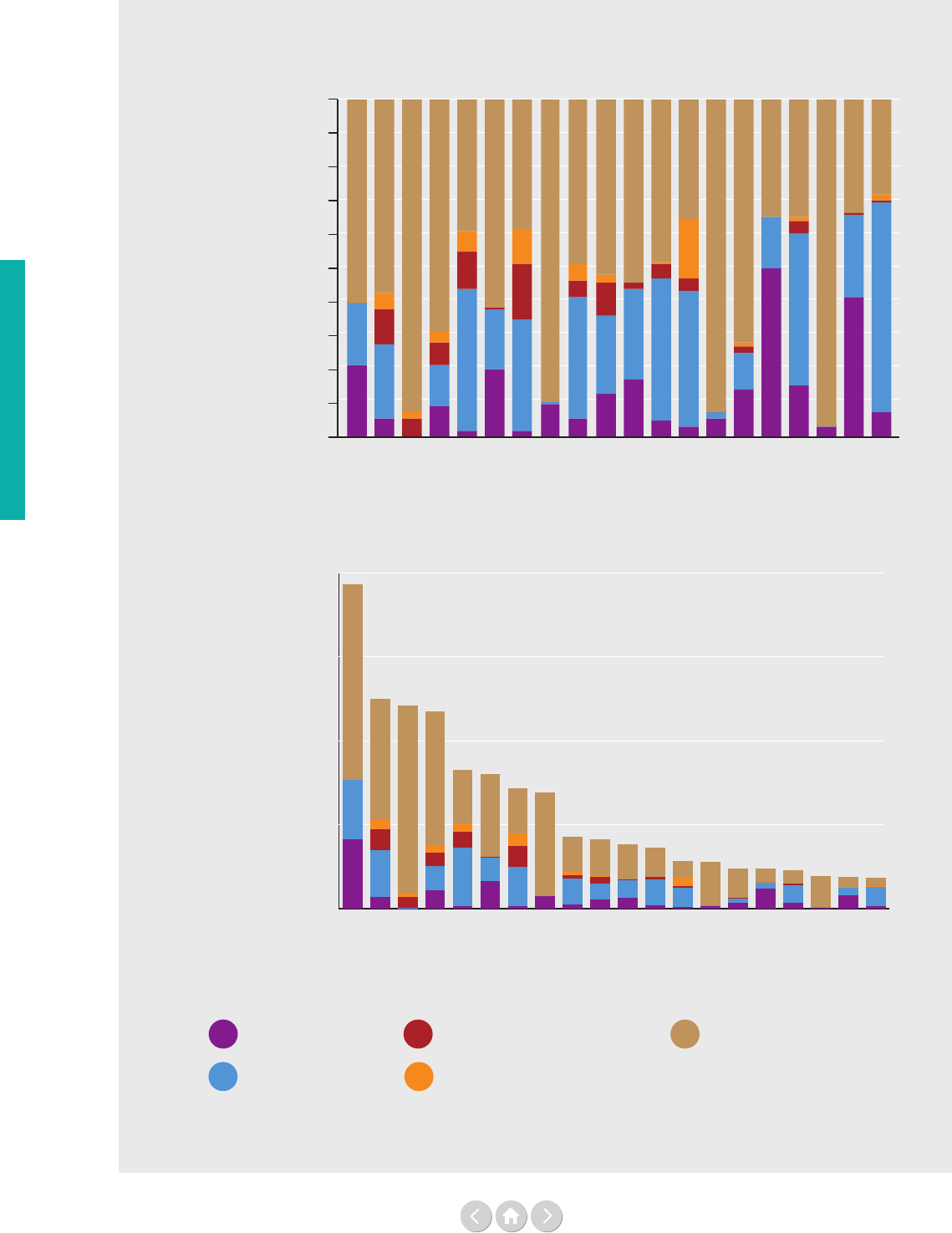

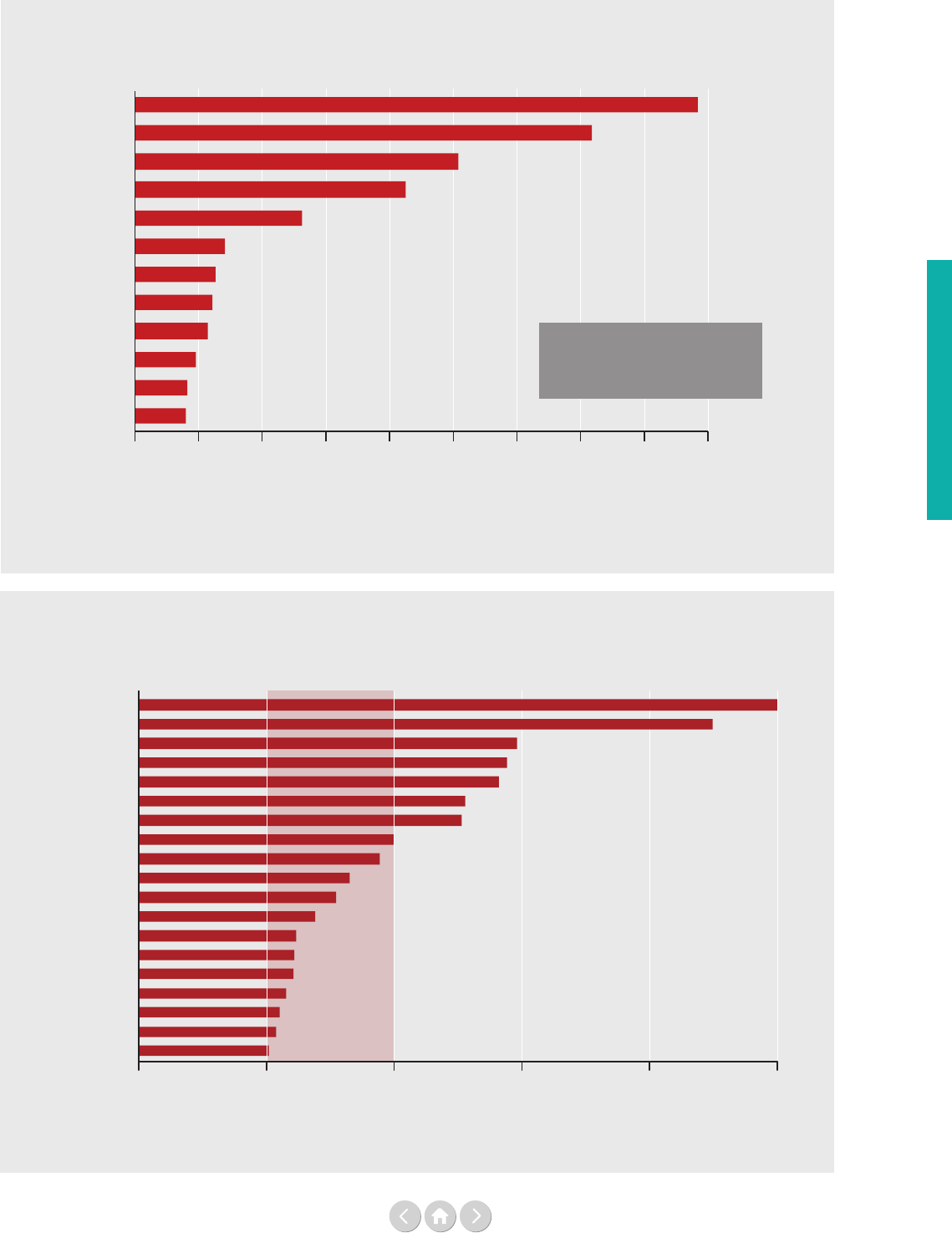

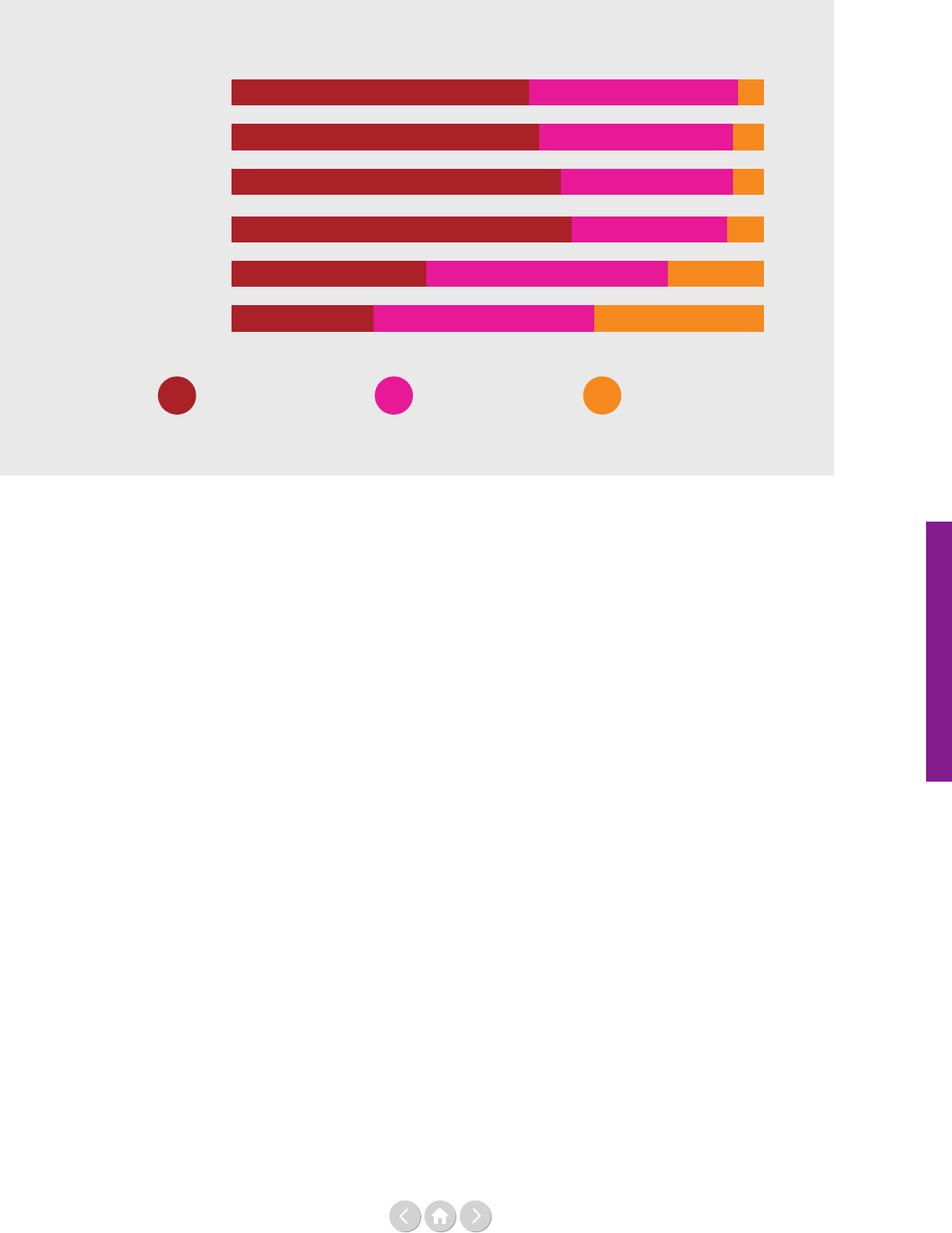

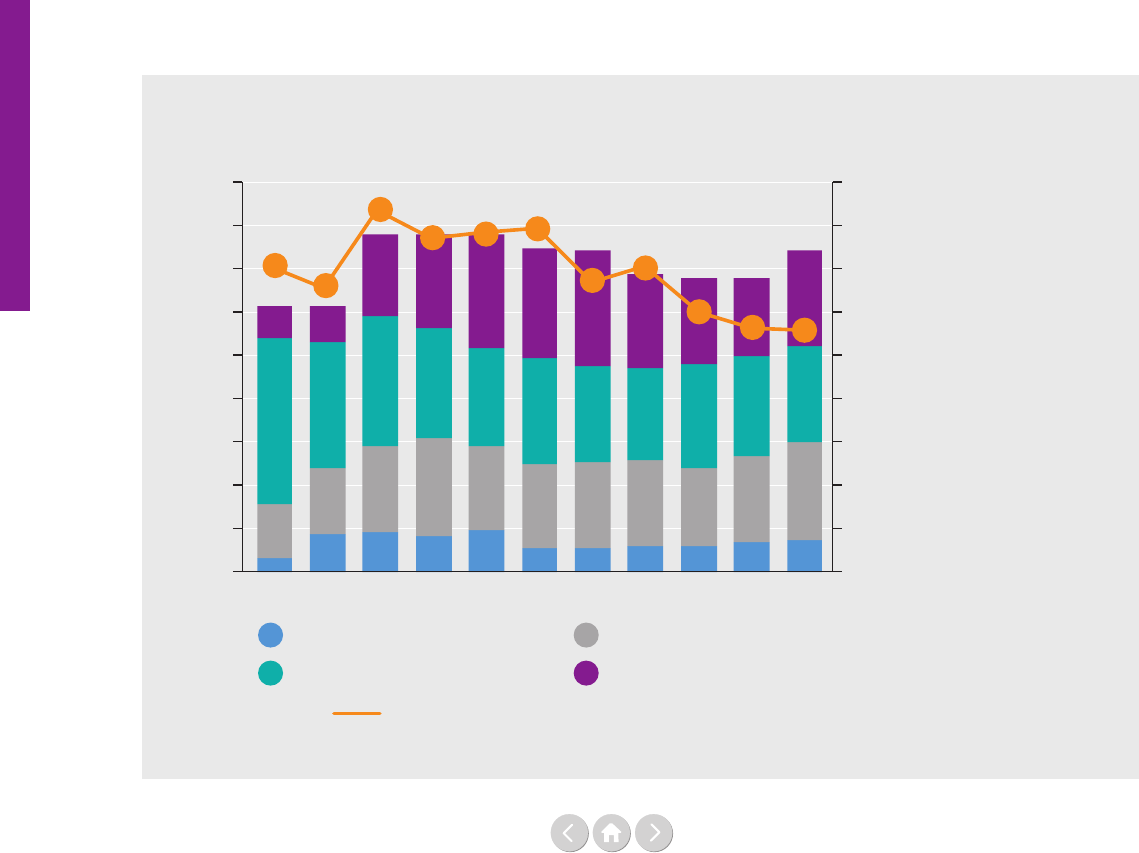

Figure 25 shows the funding mix of the top 12 OECD-

DAC contributors, with contributions broken down into

core, inter-agency pooled funds, single-agency

thematic funds, and other earmarked funds. In 2017,

these top OECD-DAC members provided 65% of the

total contributions for UN operational activities and in

the past ve years this share has grown four percentage

points (from 61% in 2013).

This analysis is complemented by an investigation into the

funding mix of non OECD-DAC countries, (Figure 26). It

shows that the top ve countries: China, Russian Federa-

tion, Colombia, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, contributed 51%

of the total funding (excluding local resources) from this

Figure

11

15

Executive summary

Funding mix of the top 12 OECD-DAC members to UN operational activities, 2017

(Figure 25 from Part One, Chapter One):

Funding mix of the top 12 non OECD-DAC countries contributing to

UN operational activities, 2017

(Figure 26 from Part One, Chapter One):

Source: see page 45

Source: see page 46

Single-agency thematic funds

US$ million

Inter-agency pooled funds

Local resources

Earmarked excluding pooled and thematic funds

Total earmarked

Pakistan

India

United Arab Emirates

Qatar

Colombia

China

Kuwait

Mexico

Argentina

Brazil

Saudi Arabia

Russian Federation

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

Core

0

1

2

3

4

US$ billion

5

6

7

= total core

14%

9%

22%

5%

44%

28%

31%

27%

42%

41%

37%

39%

Inter-agency pooled funds

Earmarked excluding pooled

and thematic funds

Single-agency thematic funds

Total earmarked

Denmark

Netherlands

Canada

Japan

United Kingdom

EU institutions

United States

Italy

Switzerland

Norway

Sweden

Germany

Core

Figure

25

Figure

26

16

Executive summary

Deposits to UN inter-agency pooled funds from the 12 largest contributors,

and share of their total earmarked contributions to the UN, 2017

(Figure 34 from Part One, Chapter One):

Source: see page 53

US$ million

0 10050 200150 250 300 400350 450

United Kingdom

Germany

Sweden

Norway

Netherlands

Canada

Ireland

Belgium

Denmark

Qatar

Australia

United States

19%

12%

30%

26%

29%

12%

50%

28%

17%

45%

1%

12%

% = inter-agency pooled fund

share of total earmarked

contributions

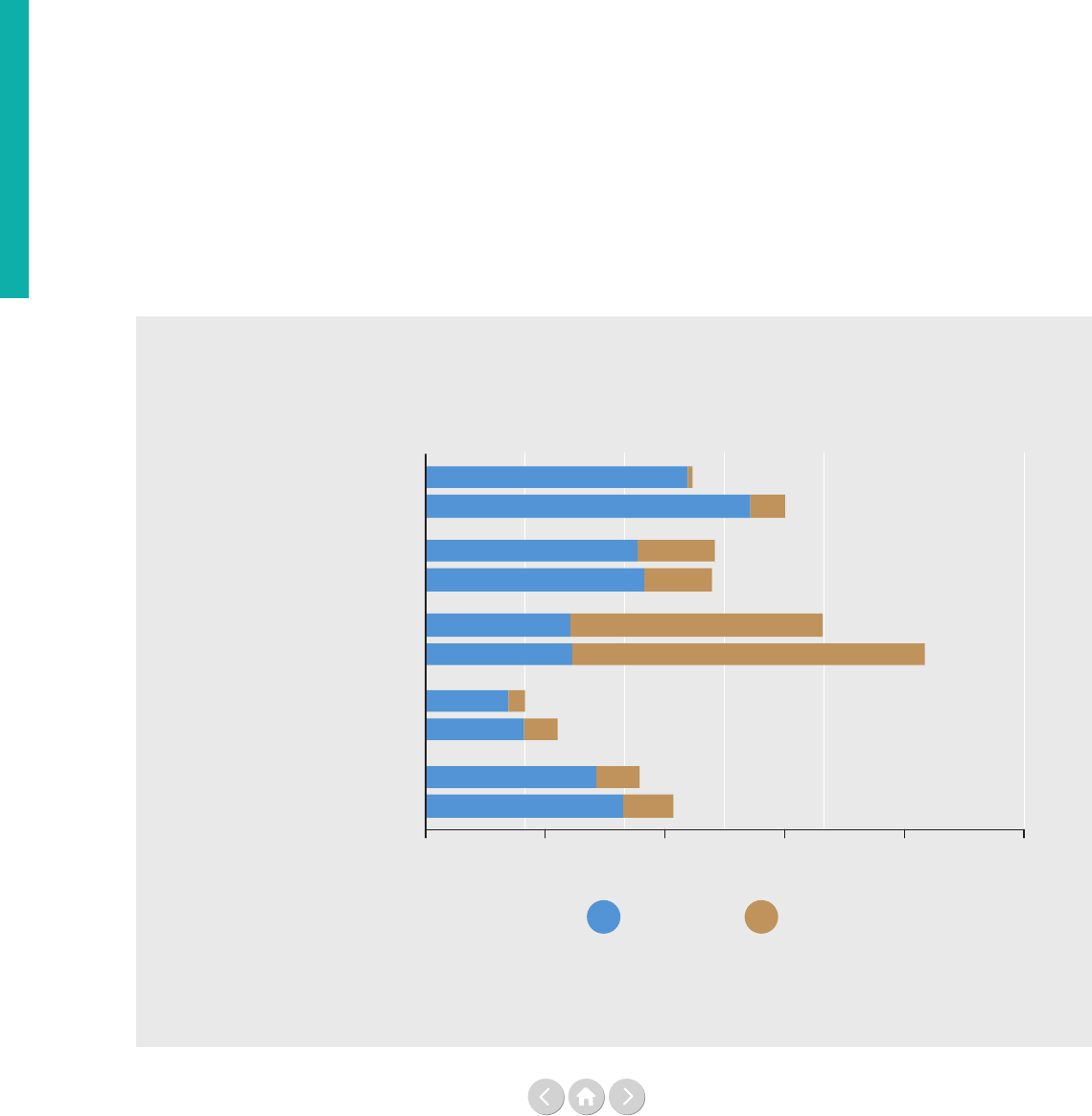

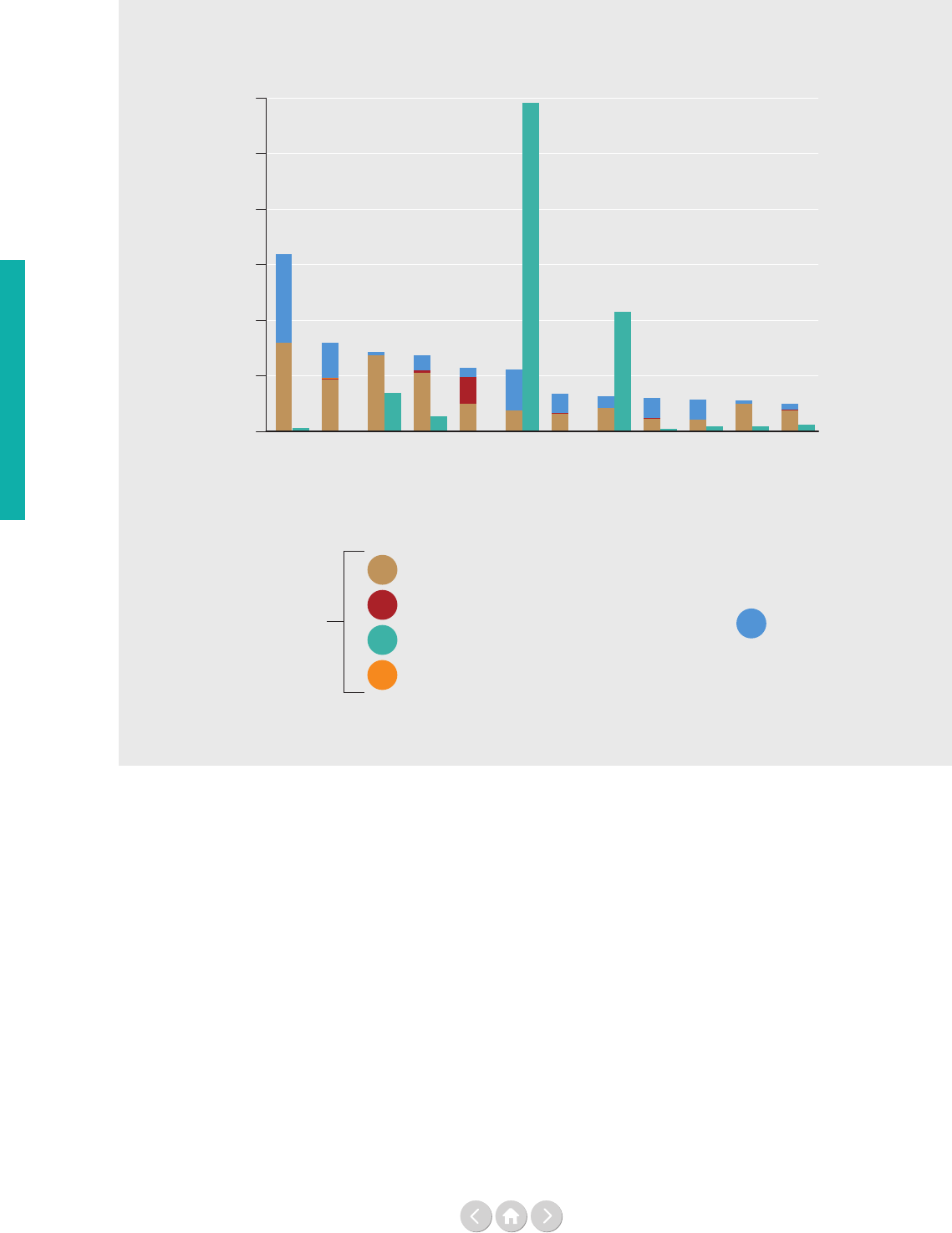

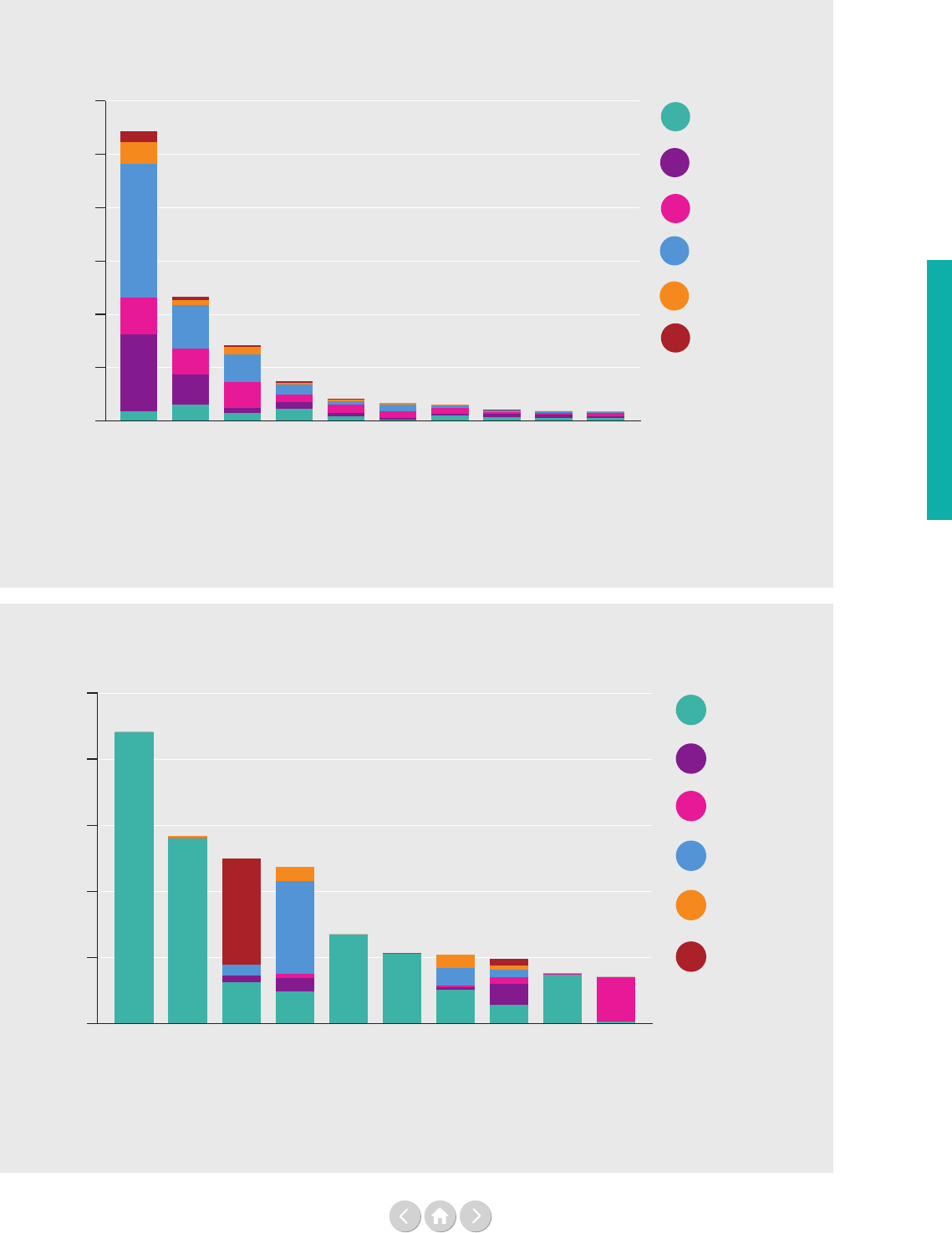

UN operational and peace related expenditure in crisis-affected countries, 2017

(Figure 38 from Part One, Chapter One):

Source: see page 57

US$ billion

South Sudan

Dem. Rep. of the Congo

Lebanon

Somalia

Sudan

Mali

Yemen

Afghanistan

Central African Rep.

Syrian Arab Rep.

Iraq

State of Palestine

Jordan

Ethiopia

Nigeria

Turkey

Uganda

Kenya

Chad

Haiti

Niger

Liberia

Myanmar

Colombia

Cameroon

Egypt

Ukraine

Sierra Leone

Senegal

Burundi

Libya

Madagascar

Côte d’Ivoire

0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5

Peace DPAPeace DPKODevelopment

Humanitarian

Figure

38

Figure

34

17

Executive summary

The report also discusses the newly adopted ‘UN Funding

Compact’ and its mutual commitments between the UN

and Member States. The core idea of the Funding Compact

is to give incentives for Member States to contribute more

qualitatively, exibly and predictably, alongside incentives

for UN development entities to increase coherence, co-

operation and transparency and make full use of eciency

gains. Several aspects of the Funding Compact are discussed

in Part One as well as in a separate contribution by Silke

Weinlich and Bruce Jenks in Chapter Two of Part Two.

Chapter Two: Expenditure

The second chapter of the report examines the expen-

diture of the UN. It provides the global picture of UN

operations in nancial terms and supplies historical data

by each UN entity, as well as expenditures by region

and by income status. It shows that among UN entities

Department for Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO), WFP,

the UN Secretariat, UNICEF and UNDP had the largest

share of expenditures in 2017.

Meanwhile, in 2017 Africa continued to be the region

with the proportionally highest UN expenditures (35%),

followed by Western Asia (23%), Asia and the Pacic

(13%), Americas (10%) and Europe (3%). Global expendi-

ture, which includes global normative work, programme

support, management and administration, constituted

17% of all UN expenditure.

With regards to UN expenditure by income status, we see

it is concentrated in low-income countries, and 48% of

the total country-level expenditure in 2017 took place in

this group of countries. Expenditure in the group of 50

countries dened as crisis-aected was in total 76% of the

total country-level operational expenditures the same year.

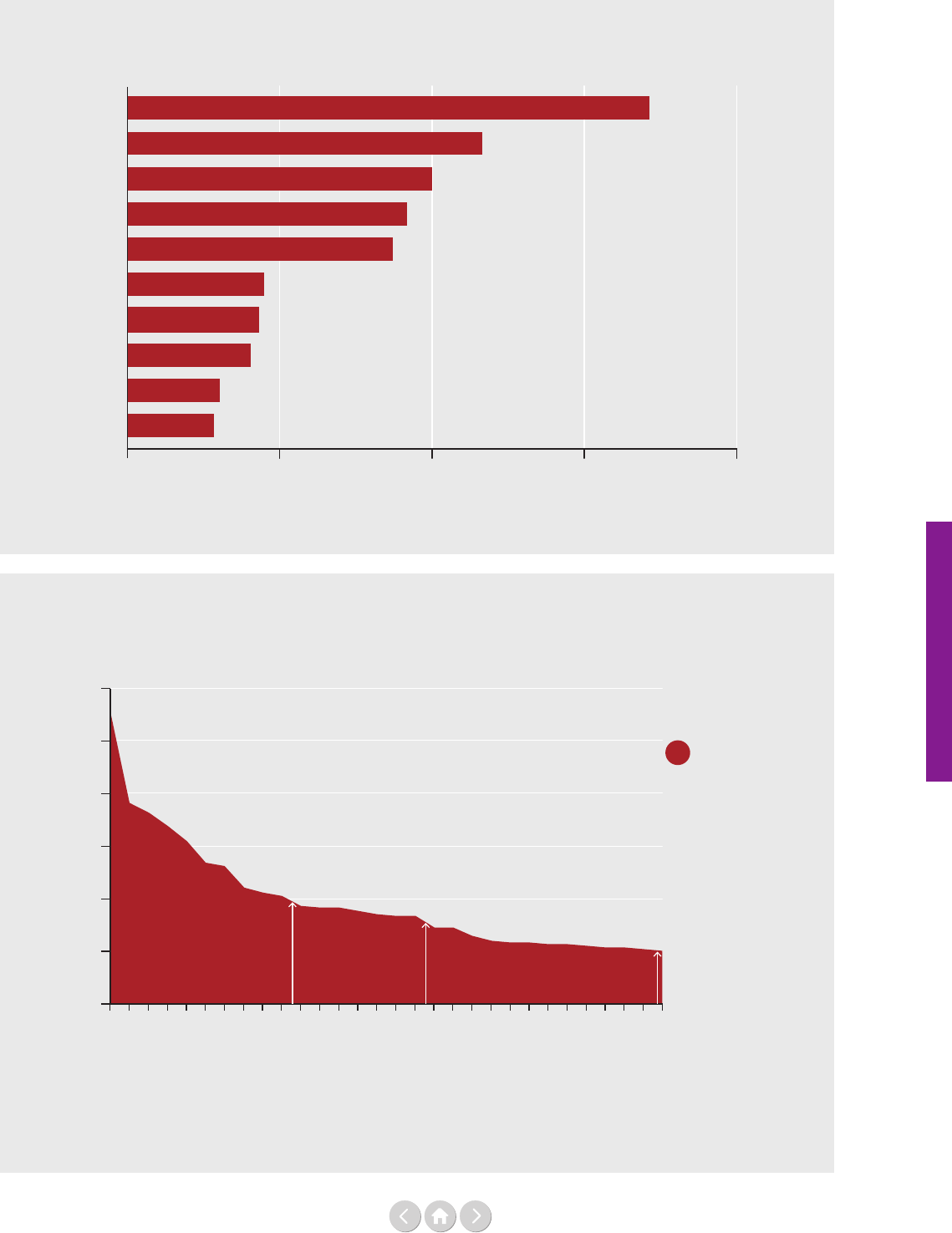

Figure 38 provides an interesting comparison between

expenditures on development, humanitarian, and peace and

security-related operations in these crisis-aected countries.

The gure shows that South Sudan, Democratic Republic

of Congo, Lebanon, Somalia and Sudan are the top ve in

terms of UN funding for crisis-aected countries; together

they constituted US$ 9.7 billion in expenditures or 19% of

the total UN system-wide expenditure in 2017. The rst

ten crisis-aected countries represented 31% of the UN’s

total expenditure – illustrating the concentration of the

UN’s work.

Overall, for this group of 50 crisis-aected countries, 24%

of the expenditure is dedicated to development assistance,

27% is dedicated to peace and security-related activities,

while 49% is dedicated to humanitarian activities.

Chapter Three: Moving ahead on data quality

Chapter Three discusses the quality issues of nancial

data and the adoption of new UN data standards. It

examines why these are crucial for our analysis and for

explaining correctly the nancial eco-system of the UN.

It also scrutinises which nancial data challenges have

been solved and what remains to be done.

It notes that most of the data analysis issues are linked

to the limitations of the two existing UN system-wide

datasets used as the main data sources for Part One.

The data comes from the CEB and the United Nations

Department of Economic and Social Aairs (UNDESA)

and these two parts of the UN system did not – up until

recently – share a common system of data governance or

a shared set of denitions. This means that the 2017 data,

used for this report and largely collected in May 2018,

has systemic aws, including dierent denitions and no

common rules for aggregating and analysing data.

However, the UN has awoken to the importance of

having good quality, system-wide nancial data. This

is clear by the major eorts made by the UN over the

past two years to improve its nancial data through the

Data Cube Initiative, which was jointly led by the CEB’s

High Level Committee on Management and the United

Nations Sustainable Development Group.

The main result was the adoption of a set of six data

standards for UN-system wide nancial reporting in the

fourth quarter of 2018. A roadmap for implementing the

data standards has also been developed. The introduction

of the data standards is not only expected to improve

data quality, but also to have a positive impact on trans-

parency and accountability as access to quality nancial

data will be improved through an online data platform.

Nonetheless, the introduction of data standards is not

the end, but rather the beginning of a longer process

of improving the UN’s system-wide nancial data.

Much more will need to be done, but this is an

encouraging start.

18

Executive summary

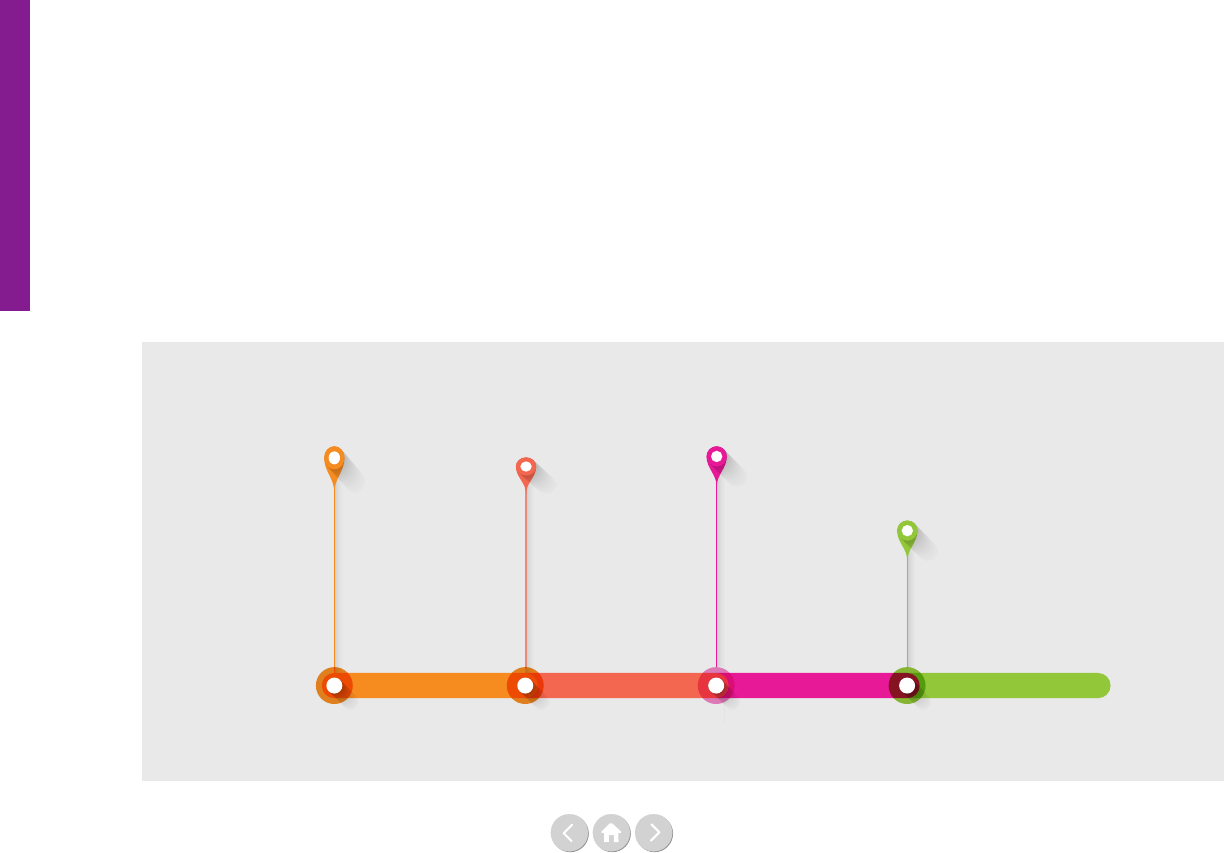

Funding of the UN system-wide activities, 2016

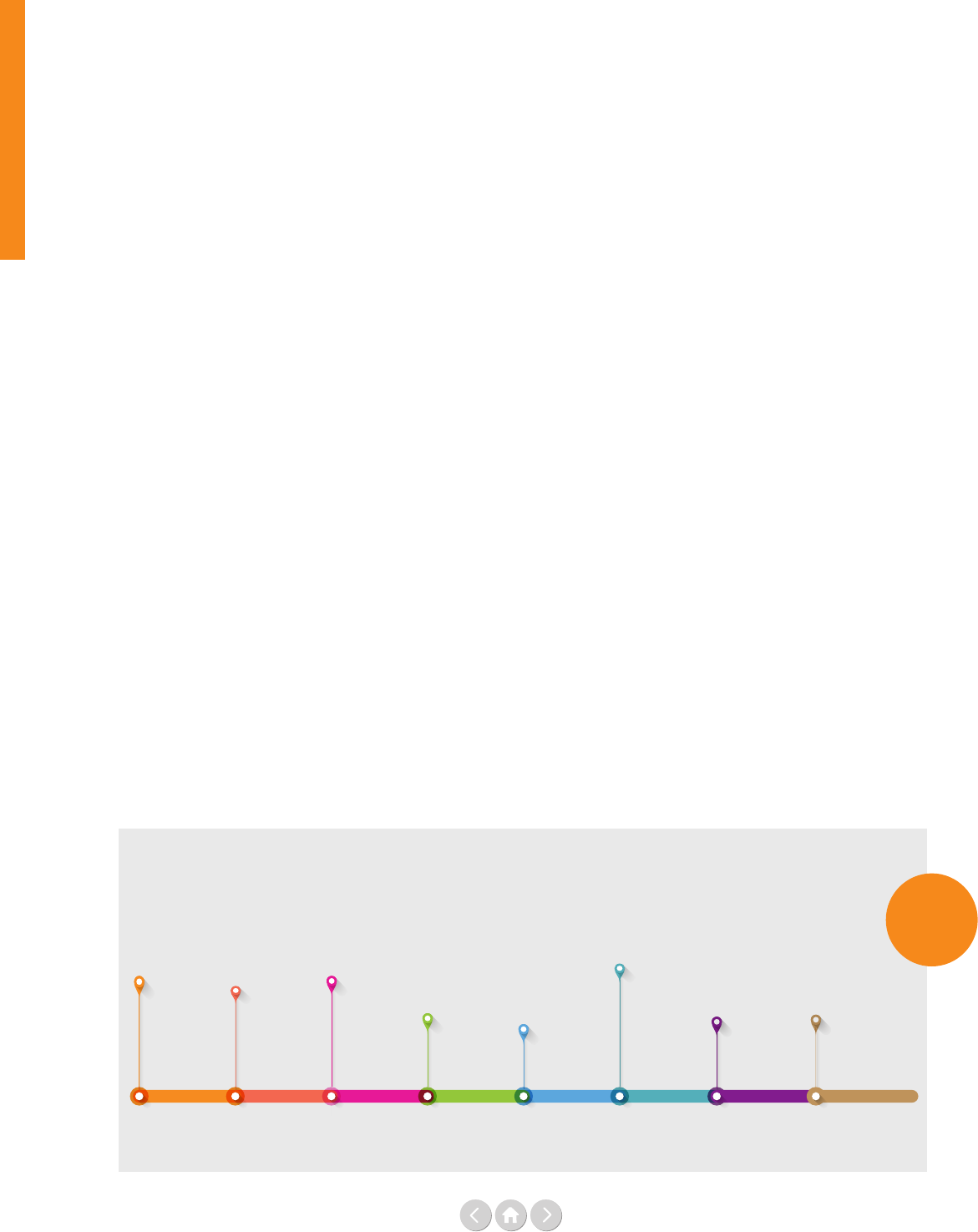

(Figure 2 from Part Two, Chapter One: International financing of the Sustainable Development Goals):

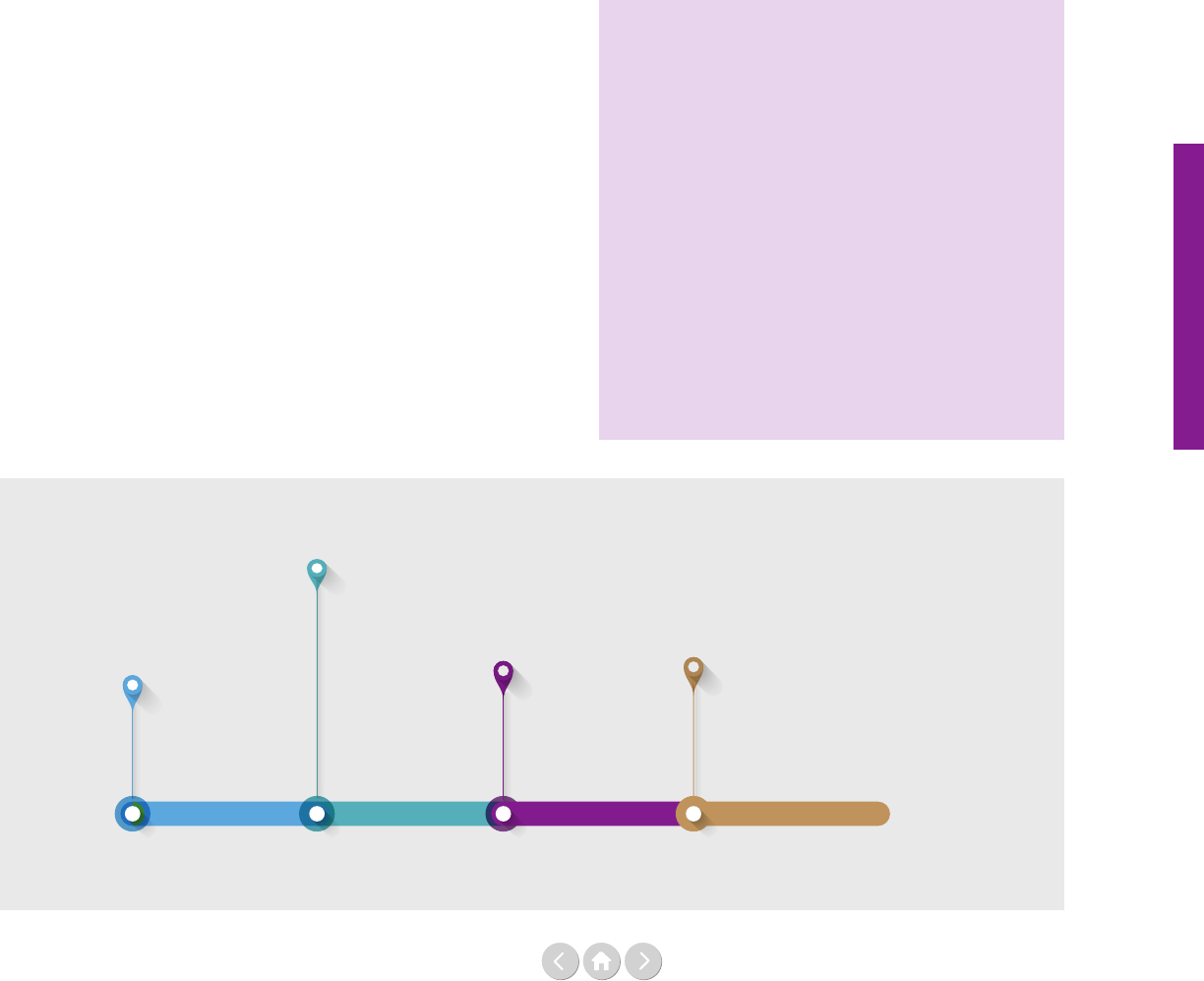

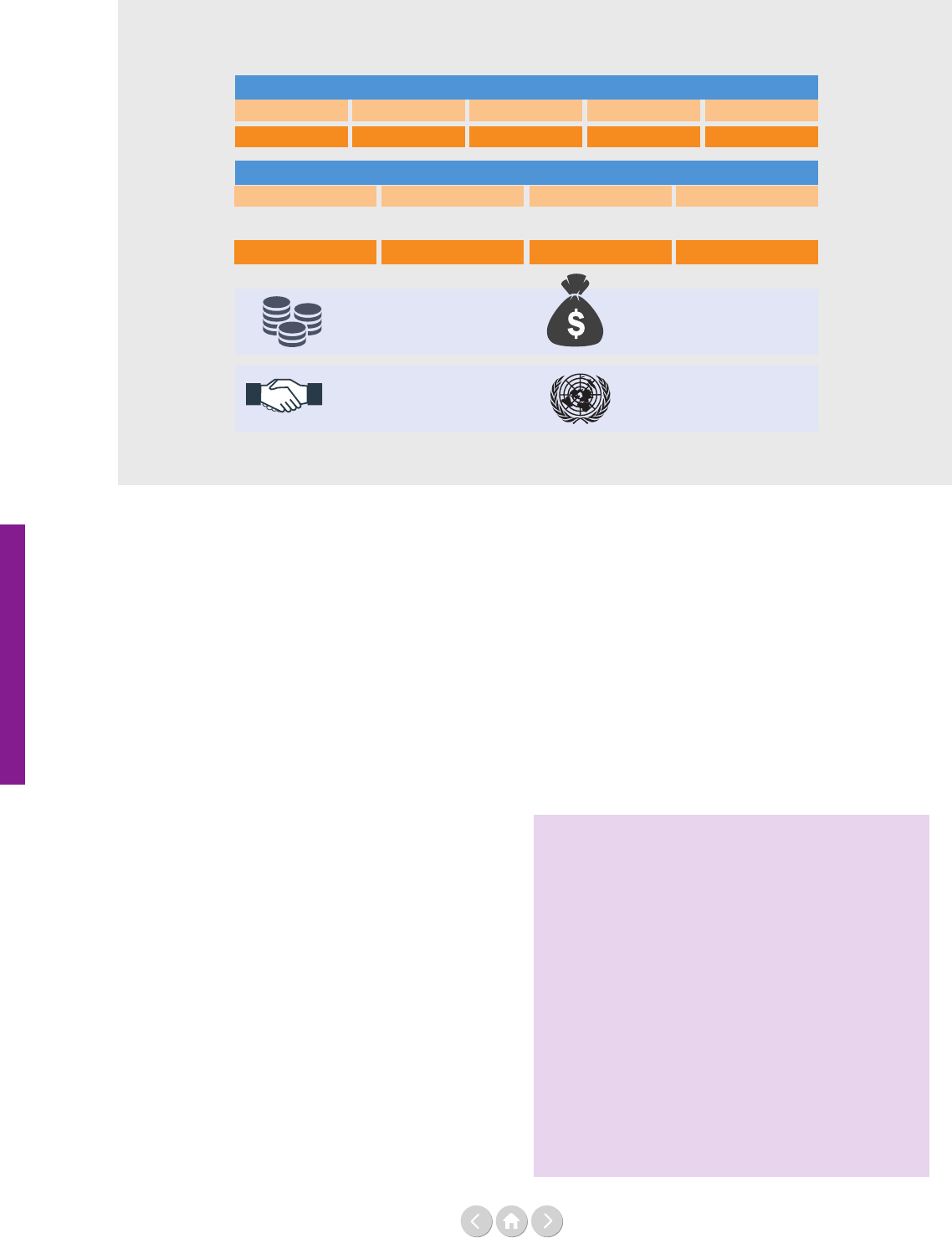

The compressed current cycle of replenishments

THE AFRICAN

DEVELOPMENT

FUND

(4th working group

meeting May 22,

2019, hoped for

funding upwards

of US$ 10 billion)

THE

INTERNATIONAL

DEVELOPMENT

ASSOCIATION

19th replenishment

- IDA 19

(pledging session,

December 2019,

funding ask upwards

of US$ 23 billion)

THE

INTERNATIONAL

FINANCE

FACILITY FOR

EDUCATION

(pledging session,

ask about

US$ 2 billion)

3rd GAVI

REPLENISHMENT

(upwards of

US$ 7.5 billion)

2019

2019 2019

2019 2019 2019

THE GREEN

CLIMATE FUND

(funding upwards

of US$ 10 billion)

2020

May

THE GLOBAL

FUND

(6th replenishment,

funding ask

US$ 14 billion)

October

September

INTERNATIONAL

FUND FOR

AGRICULTURAL

DEVELOPMENT

(12th replenishment

first consultation

session, funding

ask about

US$ 1.4 billion)

April

Autumn December mid-2020

THE GLOBAL

PARTNERSHIP

FOR EDUCATION

(upwards of

US$ 2.3 billion)

2020

Autumn

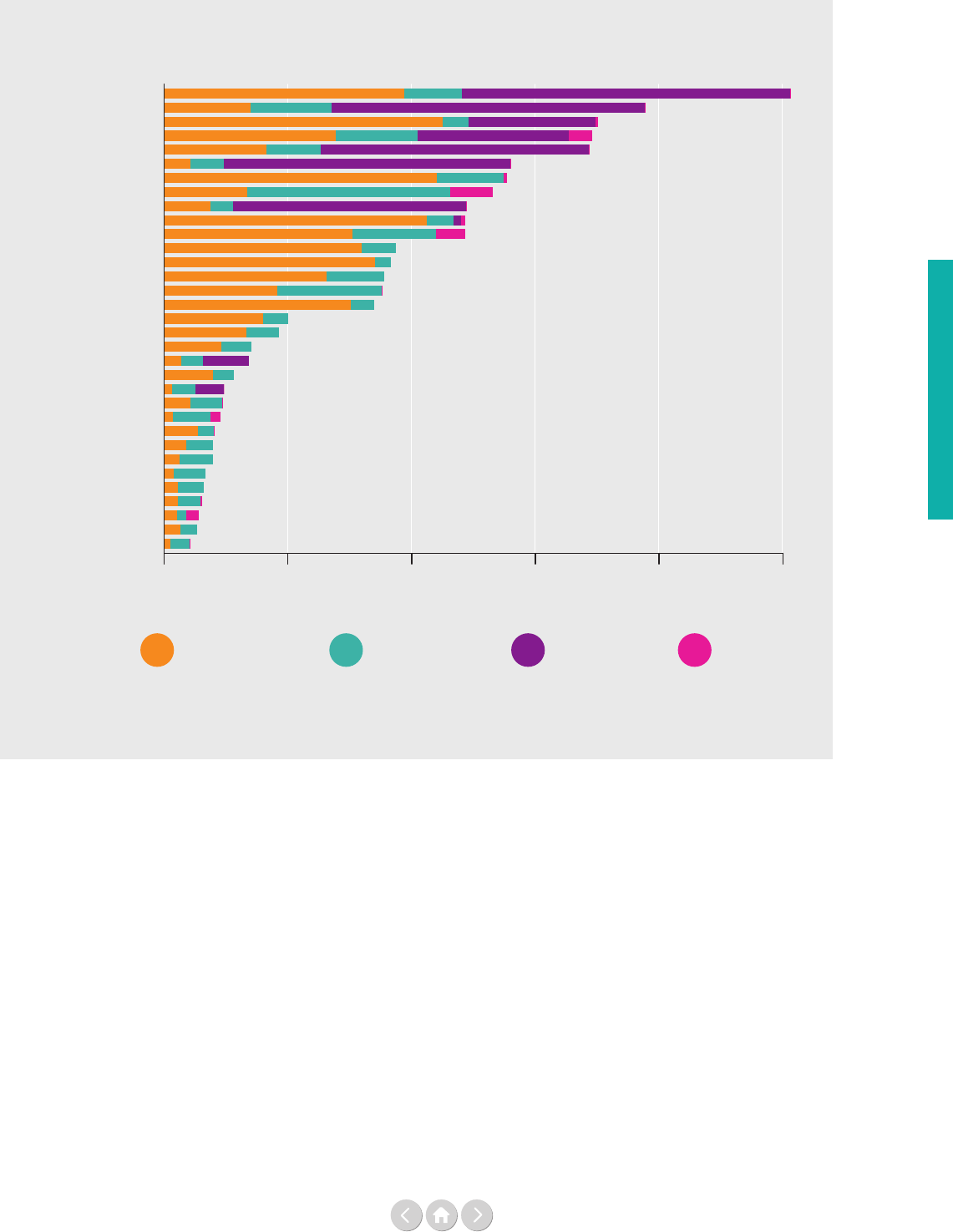

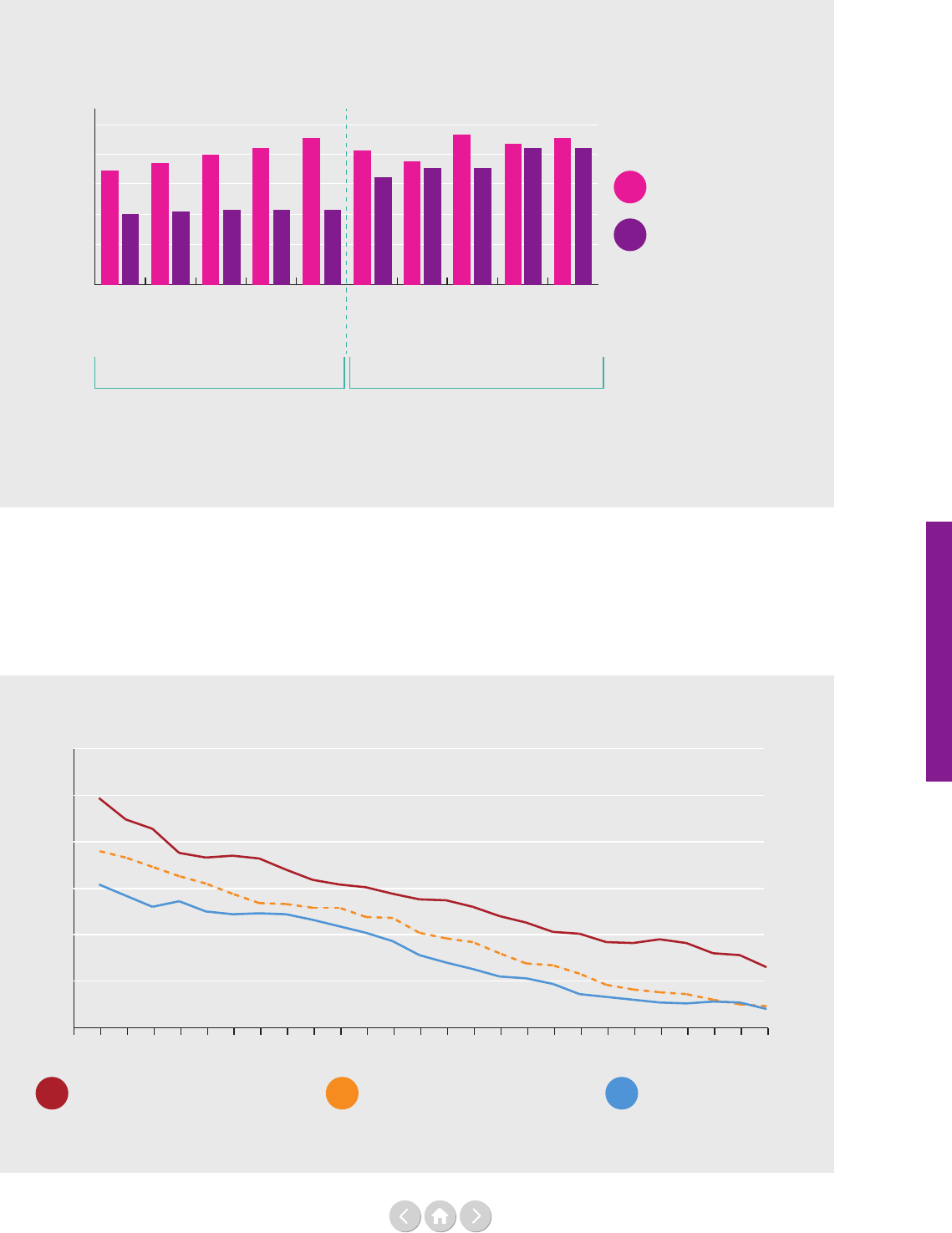

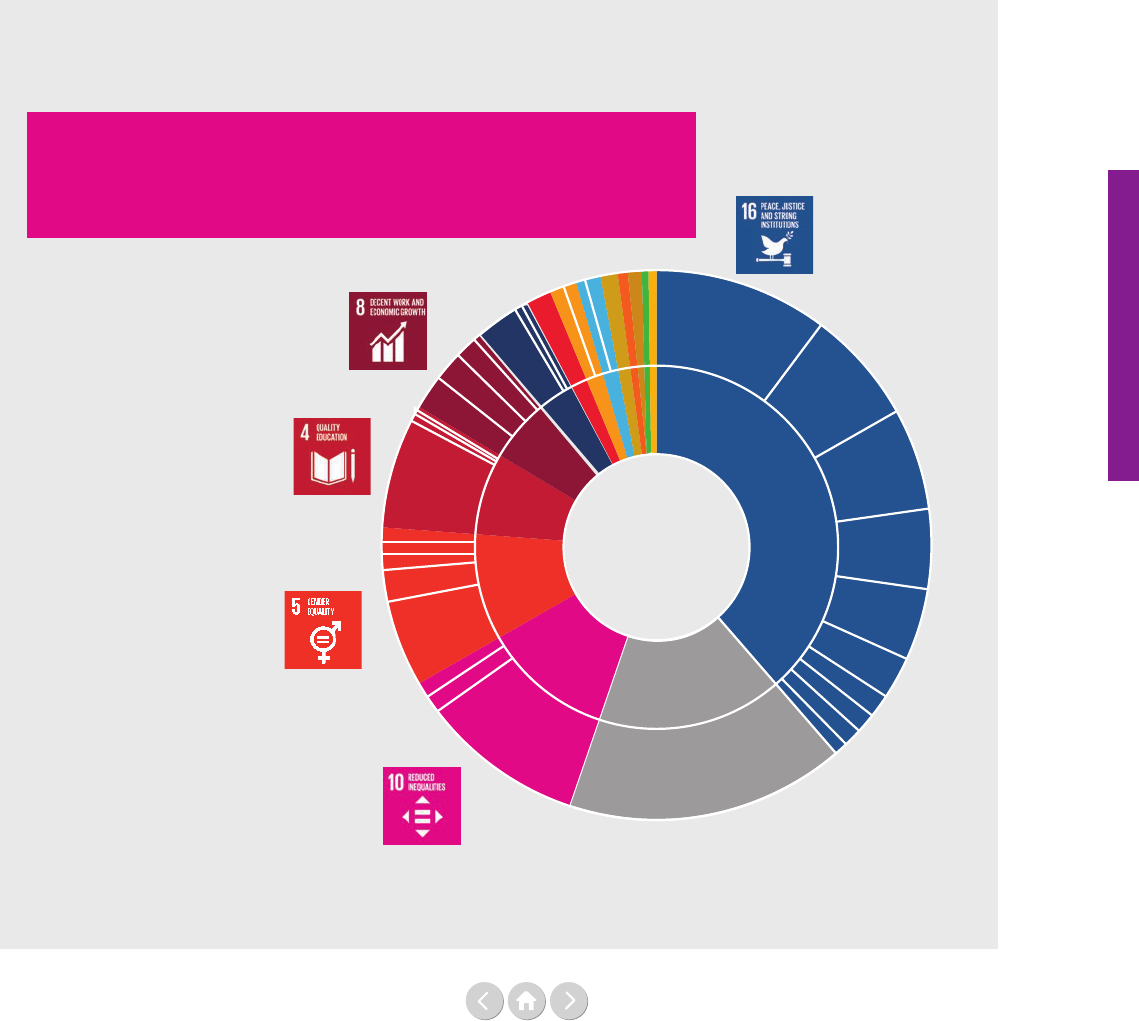

Key findings Part Two:

Financing flows impacting

the Sustainable Development Goals

The second part of the report is organised into four

chapters where guest contributors discuss some of the

key challenges facing development nance today.

Chapter One:

Financing the 2030 Agenda: The big picture

In Chapter One, contributors were invited to look at the

big picture of development nance against the backdrop

of the 2030 Agenda. Homi Kharas provides an overview

of the state of cross-border nancing of the SDGs. These

are dened as the nancing ows to developing coun-

tries that likely nance investments related to the SDGs.

He sees a signicant increase, largely due to private

ows, but notes that these private ows are volatile and

not a full substitute for aid. His concluding analysis looks

at the net impact of nancial inows and outows

together and notes that the International Monetary

Fund’s (IMF) most recent forecast for net ows to

developing countries in 2019 is actually zero. He also

notes that in 2019 and 2020, a period when aid budgets

will be tight, the replenishment cycles of several large

multilateral agencies are overlapping, so aid for one

entity might result in reduced aid for another (see the

gure below).

This is followed by a contribution from Fiona

Bayat-Renoux, outlining the Secretary-General’s strategy

for nancing the 2030 Agenda. She sees current invest-

ment levels are far from the scale and speed required, but

stresses that the resources and capacity available today

can close the existing investment gap. She notes that the

UN has a long history of supporting Member States on

nancing for development.

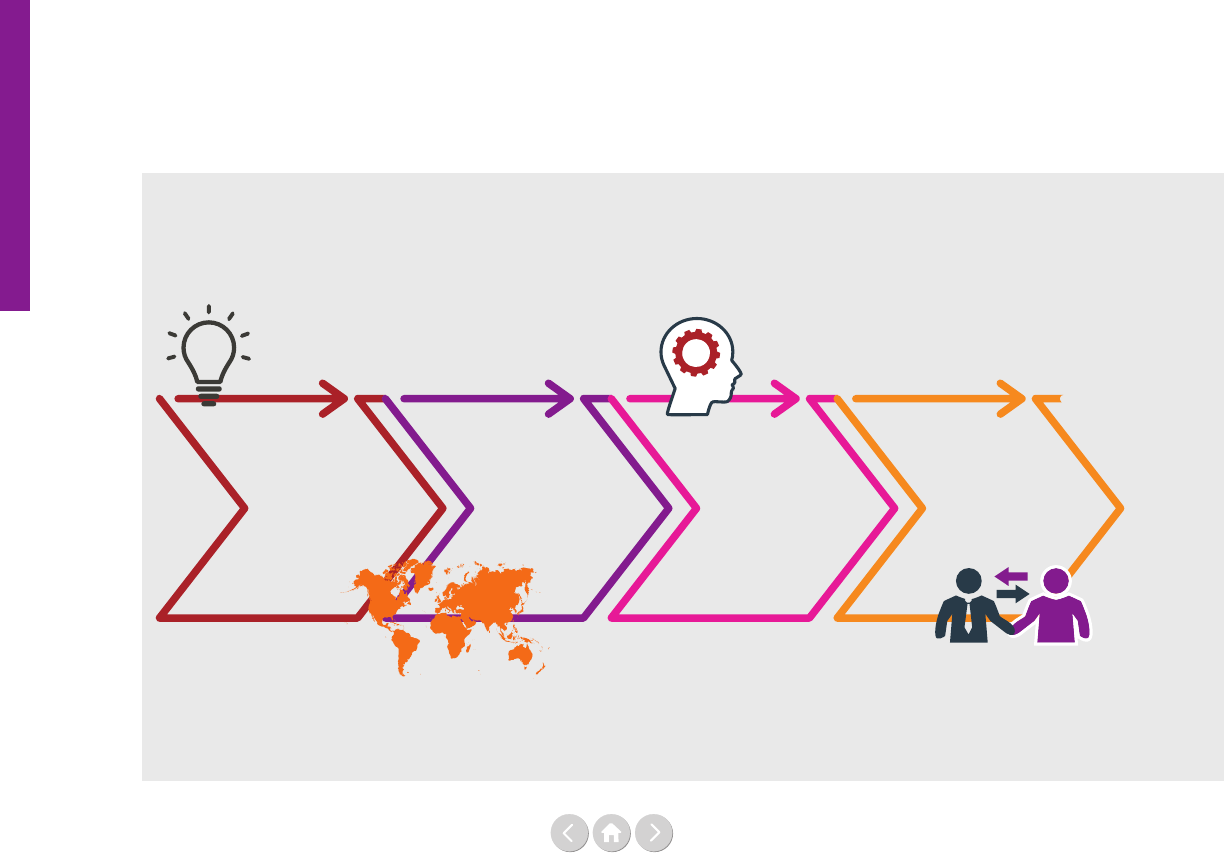

Navid Hanif and Philipp Erfurth focus on the need to

change the narrative from identifying investment gaps to

promoting investment opportunities. Rather than a gap

lling exercise, investment in sustainable development

needs to be seen as an exercise in matching investments

with investors. They argue that there is a need to change

mind-sets and perceptions both on the supply and the

demand sides.

For Ambassador E. Courtenay Rattray, achieving the

objectives of the 2030 Agenda and the targets of the

Paris climate agreement requires a massive, global

programme of investment in real assets and sustainable

infrastructure. Beyond establishing new partnerships

between the public and private sectors, as with others,

he stresses the critical engagement needed by

institutional investors. He wants to see Member States

taking concrete action and in this regard, he describes

the launch of the Closing the Investment Gap initiative

(the CIG initiative).

John W. McArthur takes us back to the country level

in his paper entitled ‘Bye-bye, billions to trillions’. He

argues that if normal global economic growth trends

continue until 2030, SDG government spending will

grow on its own by US$10 trillion per year, which more

than covers the needed incremental investment cited in

the SDG context. Bearing this in mind he argues that

the focus needs to shift from volume to purpose and

distribution.

Pedro Conceição’s paper explores the relevance of

science, technology and innovation policy in relation to

the 2030 Agenda and how they will shape inequality.

Far from neutral, they may emerge as one of the most

consequential policy areas for inequality because of the

Figure

2

19

Executive summary

impacts of the incentives that exist to foster innovation.

The key idea is that this area has little to do with mobilis-

ing resources as such and more to do with the incentives

that shape creativity and innovation to advance science

and technology in a way that generates widely shared

benets.

Chapter Two:

Earmarking: Making smart choices

Chapter Two features a number of contributions that

explore how to go beyond the core vs earmarked

conundrum. The rst paper in this section by the UN

Multi-Partner Trust Fund Oce (MPTFO) provides

an overview of UN pooled funding and discusses some

of the advantages that pooled funding has to oer. The

paper makes a persuasive case that pooled funding can

provide quality funding and oers opportunities that

might otherwise not be available to the UN system.

This is followed by a paper by Max Bauman, Erik

Lundsgaarde and Silke Weinlich which explores some of

the advantages and disadvantages of non-core funding.

The paper calls for more attention to the best mix of

various forms of funding, which allows UN organisations

to play to their strengths.

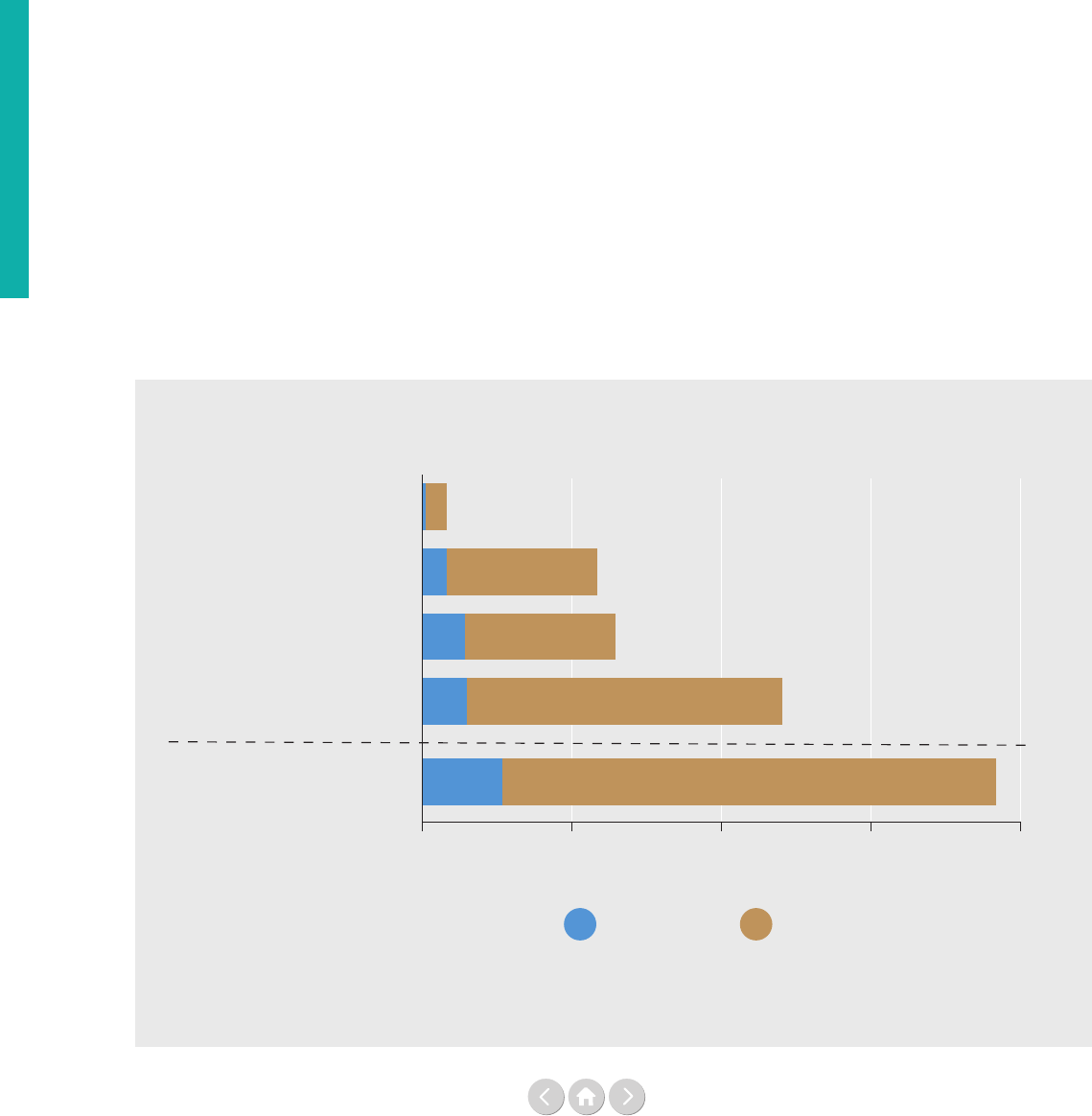

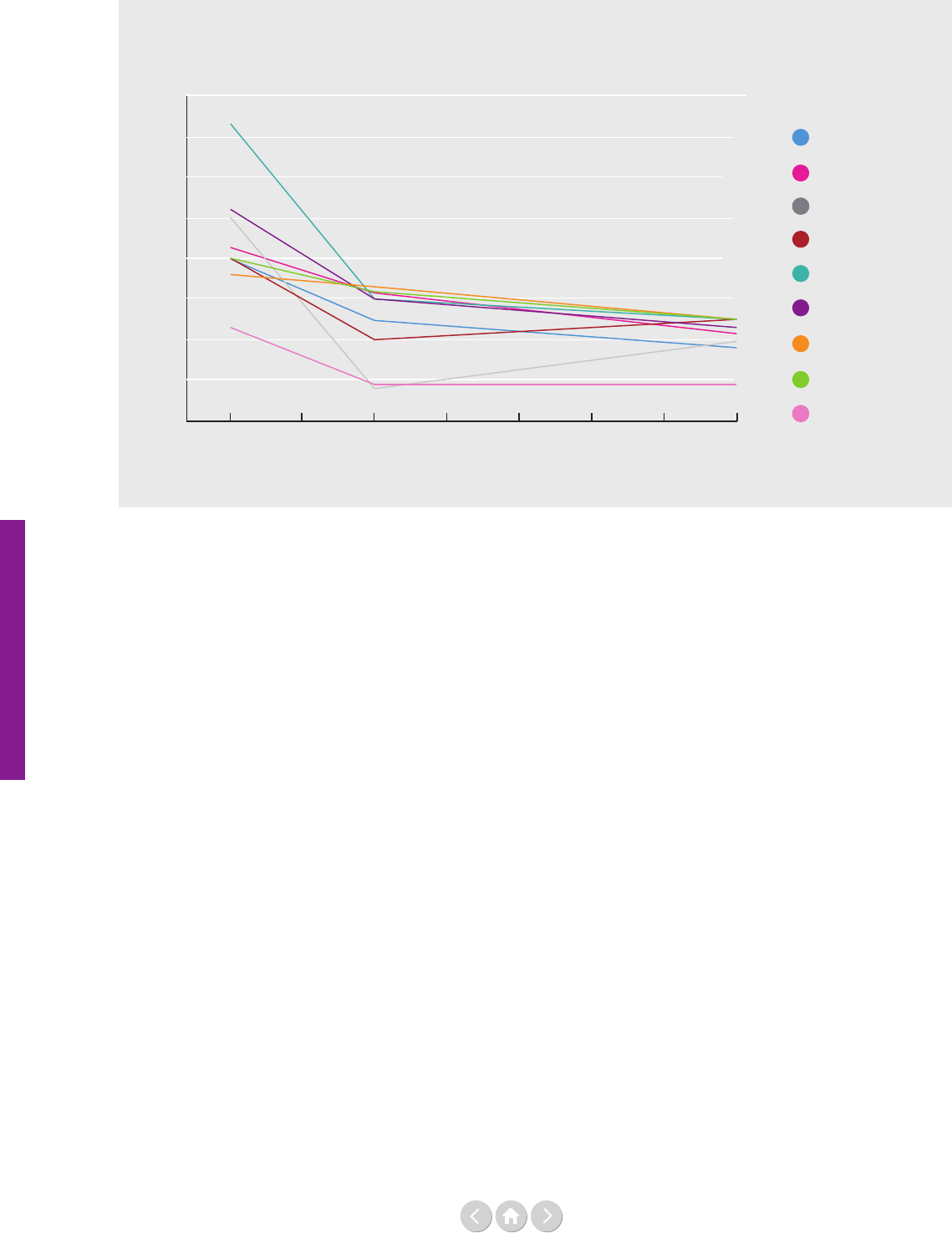

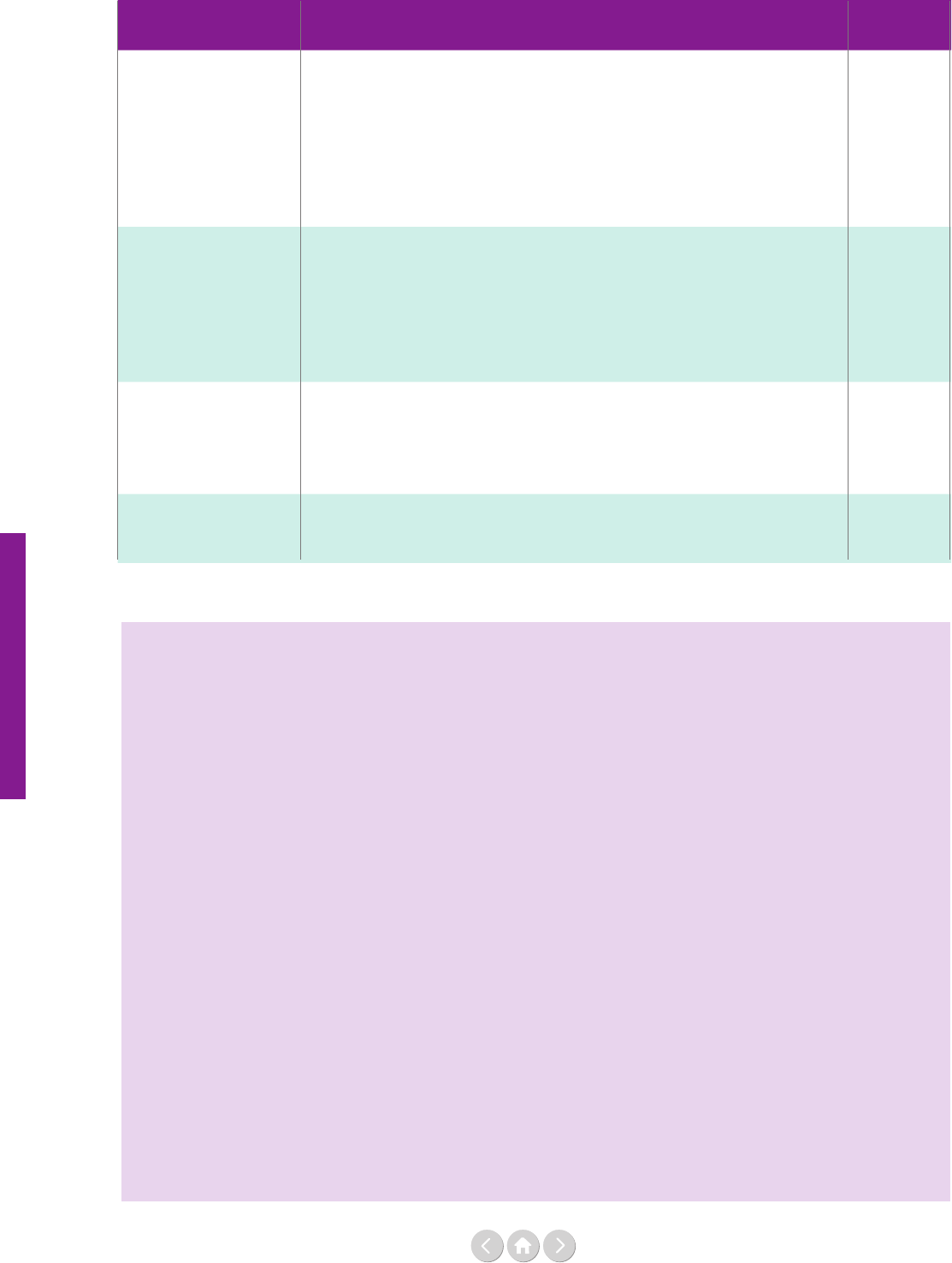

A paper by Brian Elliott and Maximilian Sandbaek

provides an overview of WHO’s approach to strength-

ening its resource mobilisation eorts as part of its new

ve-year strategic plan. It links WHO’s resource strategy

with a range of initiatives it is taking, such as WHO’s rst

ever investment case, the formulation of a draft Global

Action Plan and the development of a draft global

resource mobilisation and partnership strategy. What has

the impact of all these actions been so far? The current

nancial outlook for the approved Programme Budget

2020-2021 already shows an improvement (see Figure 3

below).

In his paper, Guido Schmidt-Traub shares lessons learned

from the experience of setting up the Global Fund

to ght AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, which was

launched in January 2003. The paper argues that success

was made possible in large part due to the unique design

principles of the Global Fund and notes that they have

applicability and should be of great interest to sector

nancing mechanisms as a whole.

Finally, the paper by Silke Weinlich and Bruce Jenks

explores the implications of the UNDS reform process

on the growth of system-wide funding mechanisms. It

argues that the Secretary-General’s UNDS reform pro-

posals and the Funding Compact have put system level

funding back on the table as a fundamental component

of a reform agenda. The paper identies ve dierent

approaches to system-wide funding that merit close

attention and then details the dierent instruments that

comprise the Secretary-General’s Funding Compact.

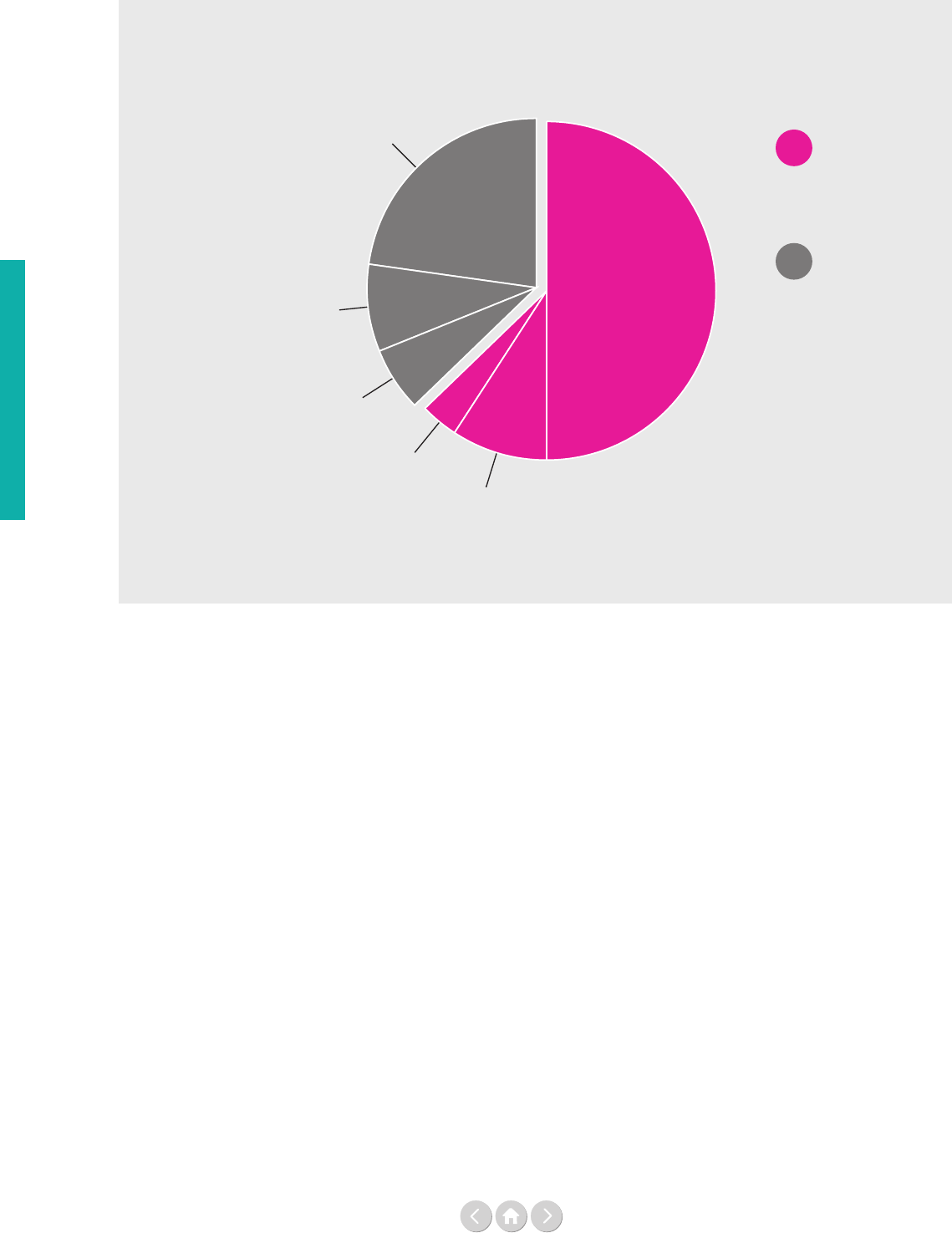

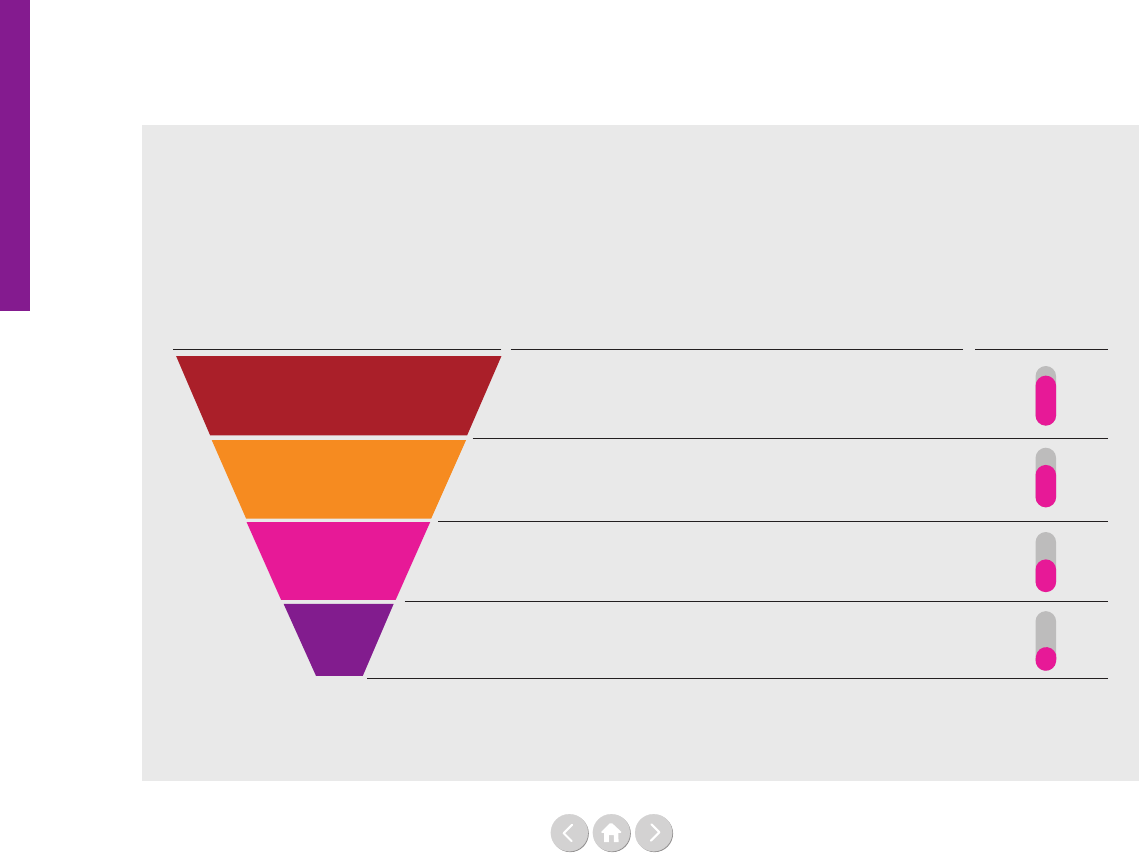

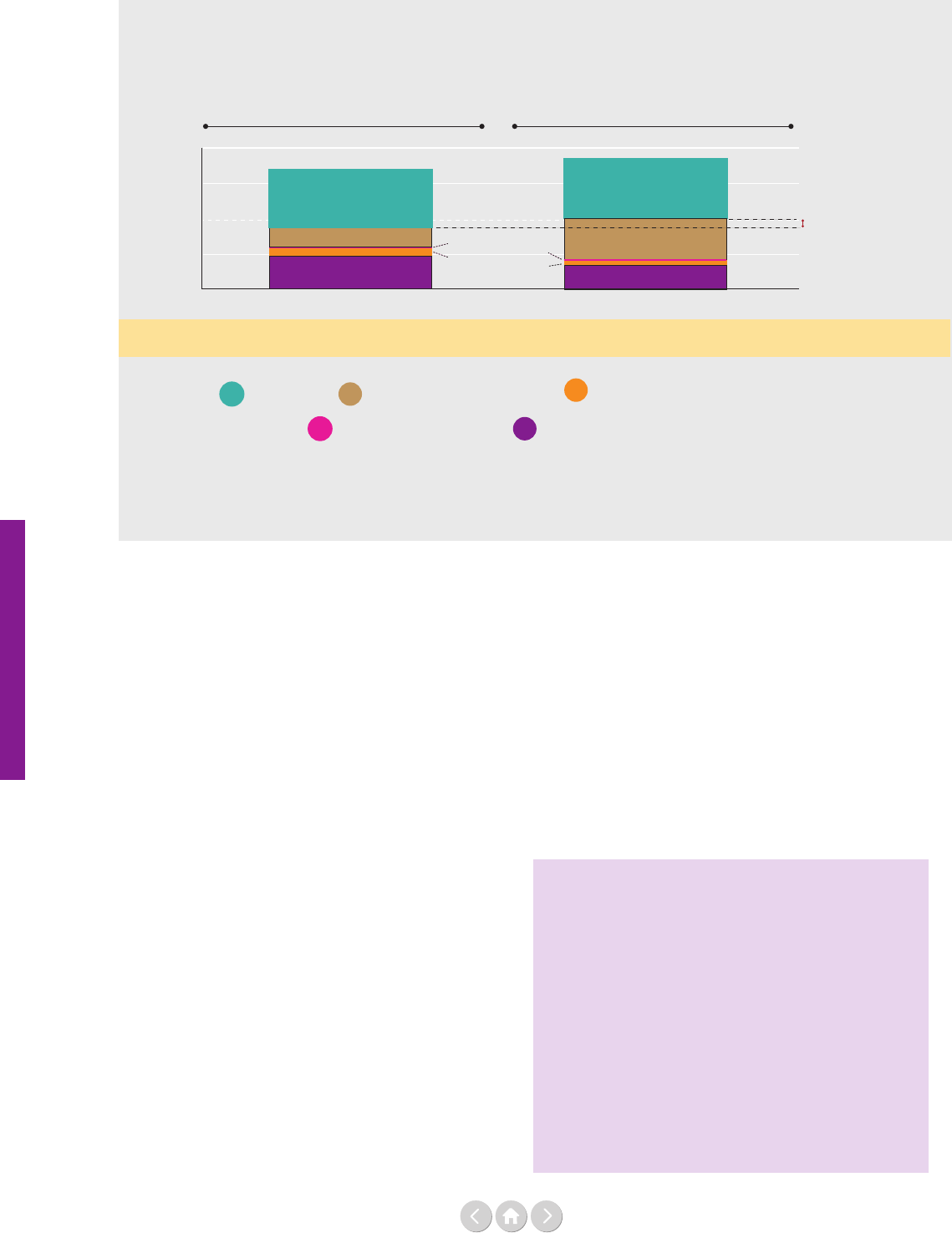

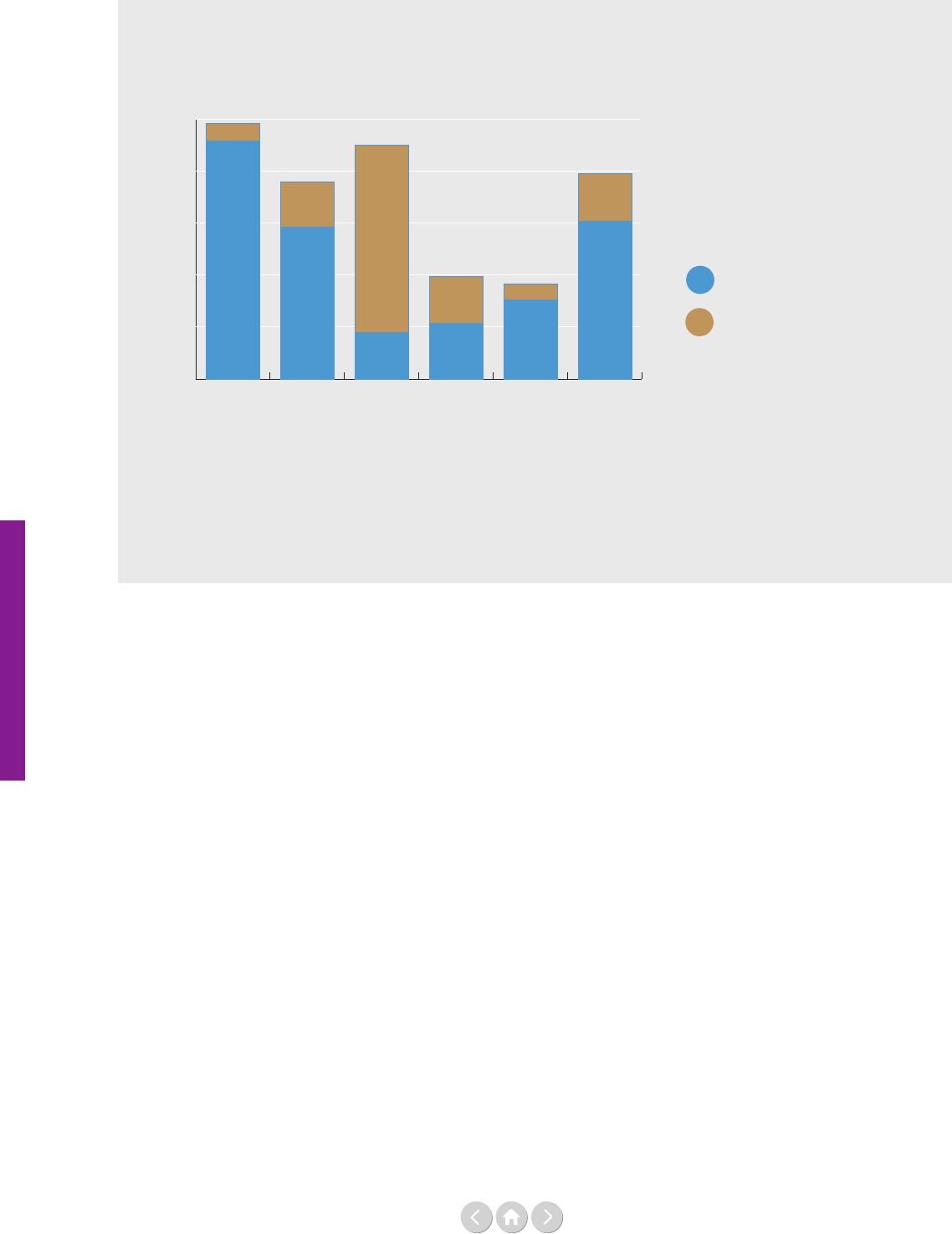

How realistic is the budget increase for 2020-21? Comparison of projected financing levels

(Figure 3 from Part Two, Chapter Two: Improving the World Health Organization's financing):

Source: see page 114

4,000

3,400

2018-2019

2018-19 base budget

(as of Dec 2016)

2020-2021

2020-21 base budget

(as of Dec 2018)

48%

45%

23%

25%

18%

28%

1%

5%

5%

3,769

312.3

3,000

2,000

1,000

US$ million

Financing

levels

Shortfall

Voluntary contributions specified

Thematic and strategic engagement funds

Voluntary core contributions

Assessed contributions

Higher projected financing

levels can largely be explained

by increases from Germany,

the UK, the European

Commission, Japan and Gavi.

52% 55%

2%

Figure

3

20

Executive summary

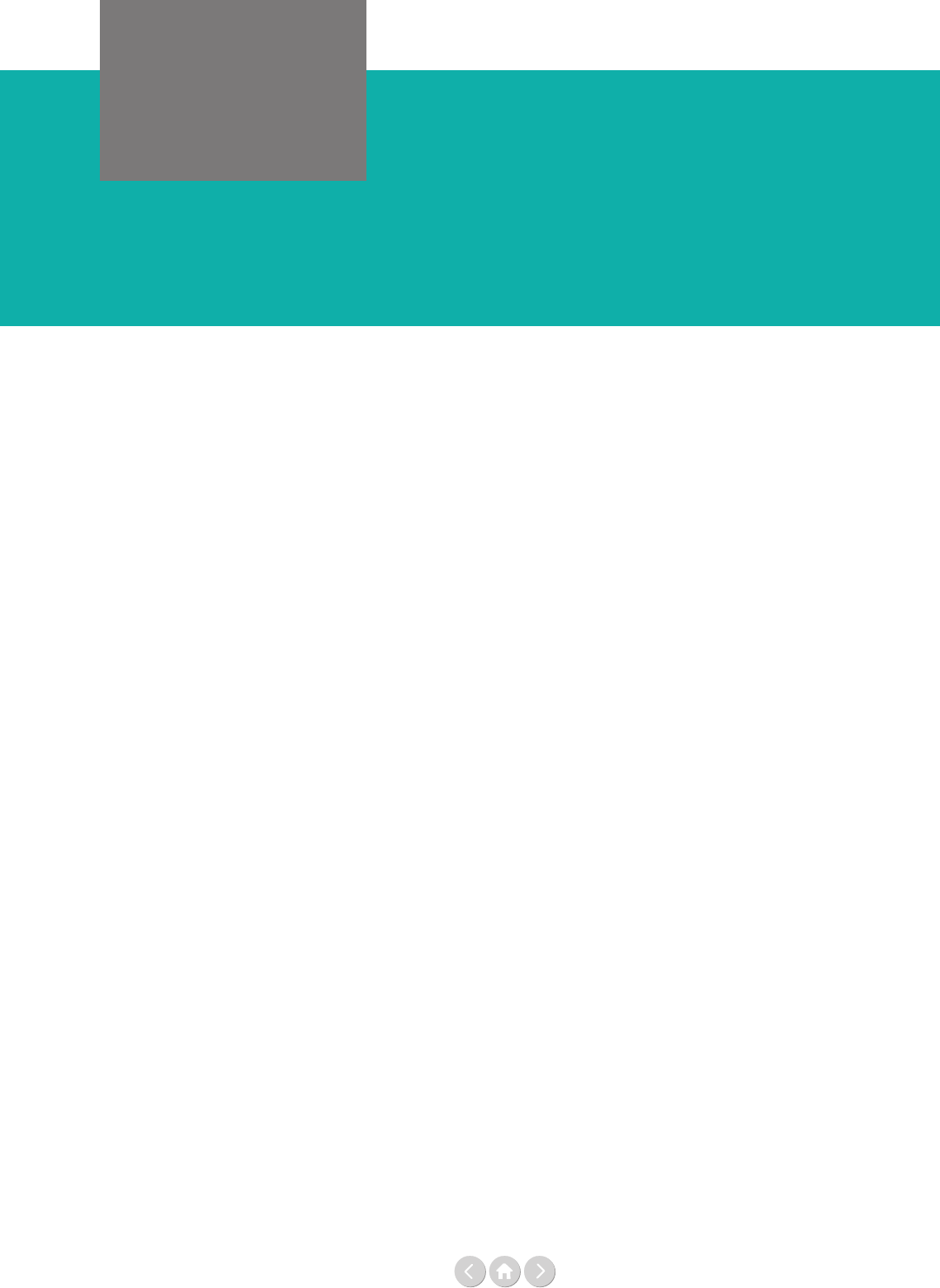

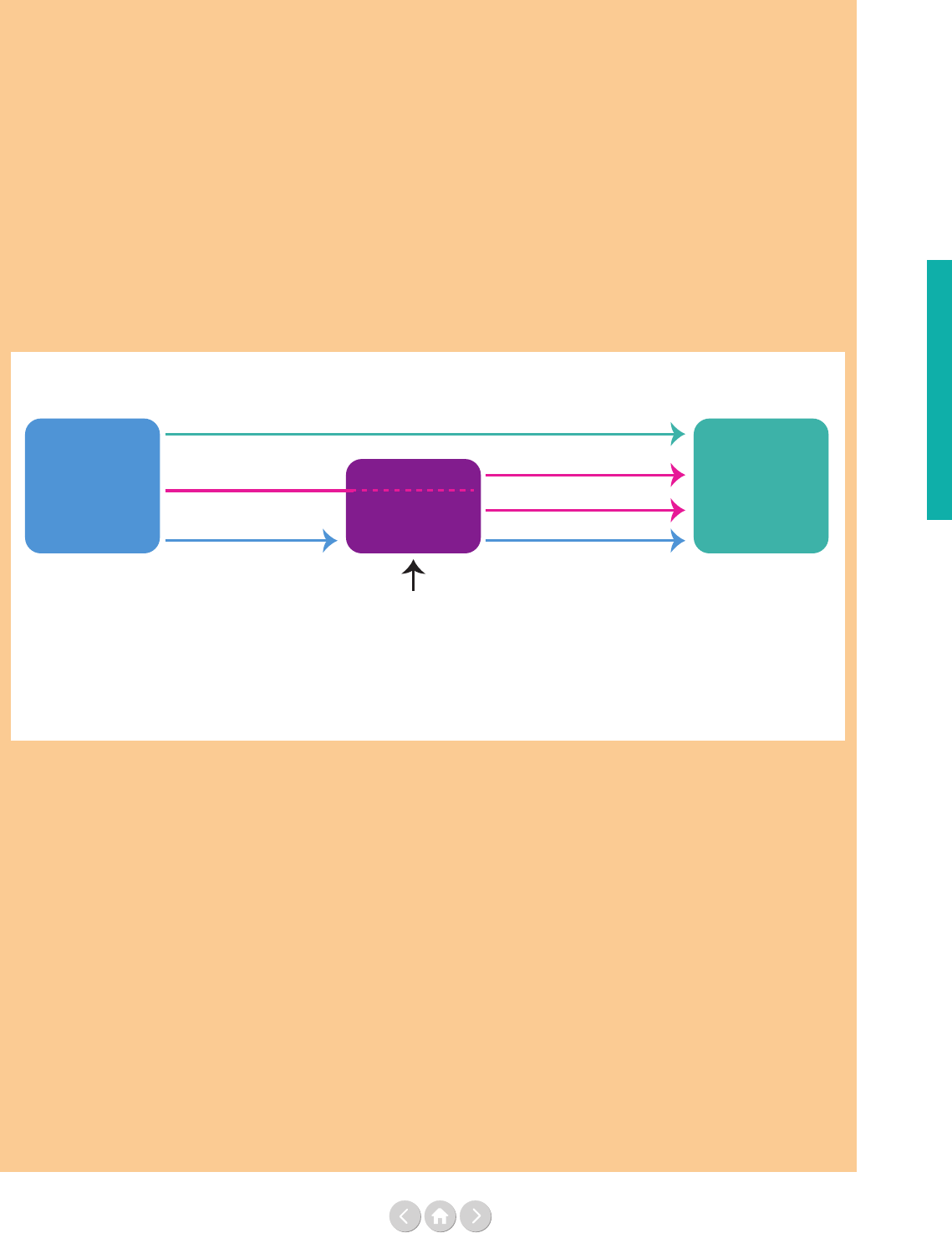

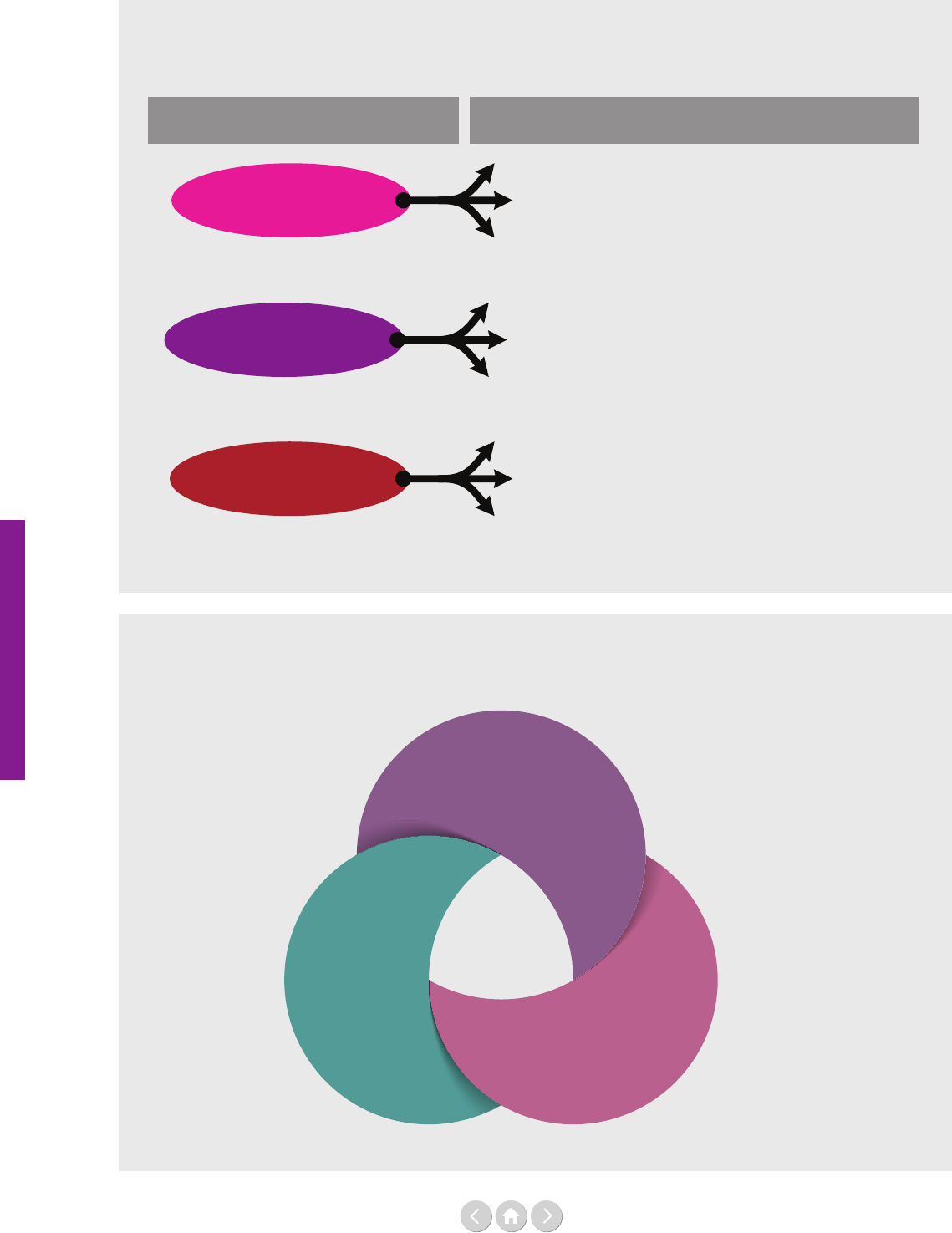

Structure of a cat bond issued by the World Bank

(Figure 1 from Part Two, Chapter Three: World Bank catastrophe bonds as an innovative development financing tool):

Country

exposed to

natural risk

disaster

Insurance contracts Cat bonds

Capital market

World Bank

Investors

Investors

Investors

Chapter Three:

Financing peacebuilding, humanitarian

assistance and migration: Time to invest

Chapter Three explores ongoing eorts and innovative

approaches to strengthen nancing for peacebuilding,

sustaining peace, humanitarian assistance and migration

in times of greater needs. In the rst piece, the Dag

Hammarskjöld Foundation, argues that beyond the

need for additional resources for peacebuilding, a radical

rethink is needed on how nancing is structured and

how to leverage strong partnerships for more eective

resourcing. The paper outlines ten points to help frame

the issues that require attention and action by the UN

and its Member States.

Franck Bousquet highlights the success of the World

Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) 18

in addressing fragility, conict and violence (FCV). He

explains that the scale-up in IDA18 from US$7 billion

to US$14 billion for low-income countries impacted by

FCV has proven critical and has helped the World Bank

adapt a more tailored response to diverse situations

of fragility.

The third piece by Catherine Howell and Henk-Jan

Brinkman explores innovative nancing options for

peacebuilding. They call for caution and note that

innovative nance is unlikely to be a panacea that brings

the ‘quantum leap’ for the Peacebuilding Fund that the

UN Secretary-General has called for or raise the needed

resources for nancing peacebuilding more broadly. They

explain that donor contributions will remain at the heart

of peacebuilding nancing, certainly in the near term.

Ayham Al Maleh looks at 10 years of ODA ows to

peacebuilding, updating the ndings of a 2017 report

by the Institute of Economics and Peace and the UN’s

Peacebuilding Support Oce. Looking at OECD-DAC

data, the article notes that peacebuilding expenditures

remain a small, and declining, proportion of total aid

disbursement to all developing countries, although this

trend seems to be halting in the most recent years.

Building on the conviction that sustaining peace and

sustainable development are complementary and

mutually reinforcing, Laura Buzzoni and Henk-Jan

Brinkman present ndings from a portfolio review of

projects funded by the Peacebuilding Fund (PBF) from

2015 to 2018 and note that PBF has contributed 83% of

its total allocations to the SDGs.

The report also highlights OECD’s Total Ocial

Support for Sustainable Development (TOSSD) pilot

study on peace and security. The pilot is based on a

consultation with a wide range of experts and a deep

dive into one specic provider country’s support to

the security sector.

Given the importance to overcome the silos, the

MPTFO oers insight on a new generation of pooled

funds that are helping to bridge the humanitarian-

development-peace nancing divide. These exible

instruments are demonstrating that well-designed pooled

funds can quickly pivot when faced with rapidly

changing conditions on the ground. The article argues

that they improve cost-eciency, transparency and

collective outcomes not only by pooling resources

and delivery systems, but also by sharing, and thereby

reducing, the risks that often arise in highly volatile and

unpredictable settings.

Looking concretely at humanitarian nancing and

natural disasters, Ambassador Lana Zaki Nusseibeh

explains the advantages of ‘forecast based nancing’ as a

new preventive tool for humanitarian response to

climate change. The article notes that while it is not

Figure

1

21

Executive summary

going to eliminate what is often a US$ 10+ billion

annual gap in humanitarian nancing, it could provide,

for the rst time, a very concrete and politically feasible

way to do what the UN and international humanitarian

system struggle to grapple with: prevent rather than react.

Continuing in the area of disaster risk management,

Michael Bennett and Rebeca Godoy of the World Bank

explain the advantages of a Cat Bond, which is a unique

type of loan that is designed to provide immediate

liquidity to countries following a natural disaster

(see Figure 1 on the previous page).

And lastly, Jonathan Prentice looks at ways in which the

recently adopted Migration Compact can be realised and

provides details around the US$ 25 million Migration

Pooled Fund. He explains that the aim is to encourage

and support the design of projects which can either be

scaled up and/or replicated as bodies of best practice.

Chapter Four: Multilateralism on trial?

Chapter Four explores new ways to forge a strong

multilateral order in times of uncertainty. Former UN

Director General of Geneva, Michael Møller sees the

instability and period of discontent as an opportunity

to revive multilateralism by injecting it with new levels

of agility, inclusiveness and partnership. He argues this

entails breaking down internal and external silos, forging

new and unconventional partnerships, increasing public

outreach and promoting openness.

In the next piece, Ulrika Modéer states that in order for

the multilateral system to regain trust and bolster the

rule-based and value-driven system, it needs to address

its discontents and evolve to be ‘t for purpose’. She

calls on Member States to show their support for and

trust in the ability of the UN development system to

meet both the promises and the responsibilities of

achieving the SDGs and increase the core-share for more

predictable funding.

Multilateralism is a hard option, argues Bruce Jenks, and

to be eective, multilateralism must be a choice that is

made because it is the most eective or ecient instru-

ment available to a government. He notes that countries

should work multilaterally when it is the most eective

way to meet a challenge. It should not become a way of

abdicating leadership; it must be a way of exercising it.

Adriana Erthal Abdenur brings a perspective on multi-

lateralism from the Global South. In her contribution

she highlights that the Global South is increasingly

frustrated that global norms are, too often, set by global

powers, and that—recent restructuring eorts notwith-

standing—deeper reform of the multilateral system is

hampered by geopolitics and outdated, unjust power

structures that date back to the post-War period. She

argues that three particular steps are needed to boost

the engagement of the Global South in the defence of

multilateralism.

In the last piece Kanni Wignaraja reminds us how

important Millennial Investors are in shaping the next

multilateral order. She notes that the millennial

generation – as leaders, consumers, self-starters and

investors – can dramatically move the needle on

inuencing SDG investments, locally and globally.

She highlights how UNDP is expanding its knowledge

on Millennial Investors and engaging with them so they

can transition from considering nancing of the SDGs as

fringe philanthropy to being mainstream better-business

for all.

Conclusion

Time is short. Not only is 2030 approaching, but there

is little time to take the necessary actions to prevent

irreversible setback and development losses. Climate

action, armed conict, disease prevention, migration,

inequality – all need urgent action and multilateral

approaches to be at the centre of global action. To make

the case for a multilateral approach, countries, leaders,

investors and citizens will need evidence of where and

in which areas this approach is the most eective option

to achieve the goals we aspire to globally, nationally and

locally. This is the rst hard choice, out of which the

nancing choices ow.

This report has attempted to provide the necessary

evidence, showcasing the funding of the UN development

system and its role within the nancing dynamics of the

2030 Agenda. A number of headline messages and

questions have emerged from this work.

What kind of multilateralism supports nancing and

funding of sustainable development and is there a

sucient sense of urgency and evidence for meaningful

investment? How do global norms get funded and

support these larger investment and nancing choices?

Does the big picture of nancial ows to development

countries – apparently increasing – point to any net

impact?

How can some of the most impactful drivers of change

– technology, science and innovation – help to reduce

inequality, ‘leave no one behind’ and leapfrog transforma-

tion? And what are the nancing approaches most likely

to accelerate these drivers? How can impact be credibly

measured to underpin hard investment choices and track

outcomes and return for future investment? What are

today’s (and tomorrow’s) models of ‘good multilateral

donorship’? And where are the pathways to ensure the

model becomes a rm structure?

22

In order to support countries in their achievement of the

SDGs, the required repositioning of the UNDS was

advanced by recent milestones. These include the

Secretary-General’s 2018 reform agenda adopted by

Member States, the major global nancing events for

sustainable development held in 2018 and 2019, and the

Funding Compact with Member States. These steps, if

well reinforced can serve as nancing cornerstones for the

UN’s contribution to a stronger multilateral order. The

hard choices ahead rest on further strengthening this

multilateral foundation, where strength is needed

especially in times of uncertainty.

Executive summary

23

Introduction

An important challenge is embedded in the title of

this year’s report: Time for Hard Choices. In a nancing

world which is both simple and complex, the choices are

numerous and what follows are hard decisions about the

allocation of resources. A multilateral approach to today’s

global challenges will need to use evidence to show its

competitive advantage. From here on, the nancing

questions ow.

The intention of this report is to wake us up to the reality

that the nancing of the United Nations development

system (UNDS) is currently in the spotlight of a complex

reform agenda. At the same time, nancing is a crucial

dimension of a multilateral approach to addressing the

world’s urgent development challenges. The report show-

cases the complexities and inno vations within Sustainable

Development Goal (SDG) nancing and the need for

a rm multilateral approach when it is best for SDG

achievement.

Over the past year, the extensive discussions and negotia-

tions around the 2030 Agenda implementation have

been increasingly focused on aspects of nancing. The

High-level UN summits on sustainable development

nancing in 2018 and 2019, major ongoing global fund

and International Financial Institutions (IFI) replenish-

ment exercises, as well as negotiation of a rst-ever Fund-

ing Compact for the UNDS are all expressions of these

nancing choices, approaches and innovations. And far

away from UN and IFI conference rooms, similar discus-

sions are taking place in private investors forums, company

boardrooms and country-level strategy meetings.

As previous reports have highlighted, the exact numbers

on the aggregate annual nancing needed to achieve the

17 goals vary widely depending on calculations, but all are

in the trillions. There is a consistent realisation from the

range of estimated gures that traditional aid, consisting of

mainly Ocial Development Assistance (ODA), will be

far from enough. Currently estimated to be US$ 140

billion annually, ODA is a mere 3 to 4% of the total

needed, but it remains a vital nancing ow especially for

low-income and conict-aected countries.

In this report, we look at how and why the UNDS fund-

ing ecosystem – underpinned by US$ 53.2 billion in total

UN revenue in 2017 – can and should interact with the

wider SDG nancing landscape. Emerging issues this year

are how nancing can more eectively support a ‘leave no

one behind’ agenda and how the ‘big picture’ of nancial

ows to developing countries inuences the role of the

UNDS in dierent country contexts. It dives deeply into

the challenges and opportunities for nancing related to

conict prevention and peacebuilding. The report looks

again at the role of nancing as it relates to technology,

digitalisation, science and, for the rst time, at the purpose-

ful investment of young millennials.

Successfully making the hard choices and investing with

intent in the SDGs will require leadership. Countries

must recognise when the multilateral option provides

added-value and is the most eective approach to meet

urgent global challenges – climate change, health,

migration, armed conict and inequality. New partner-

ships and engagement with investors are required to close

the investment gap.

This is the fth annual report of Financing the UN

Development System and maintains the basic structure from

previous reports. Part One provides accessible UN fund-

ing data on revenue and expenditures, which we believe is

important for understanding current and future nancing

24

Introduction

reform discussions. This year’s report includes references to

two new initiatives in the UNDS funding landscape, the

Funding Compact and the 1% levy on tightly earmarked

contributions. It is important to note that as these reports

have grown in ambition over the ve years of production,

so has our attention to the underlying data and current

denitions. While there is a wealth of statistics to draw

from, there are a number of challenges with data quality,

as was highlighted in the 2018 report, making in-depth

analysis at times dicult. Thus, again this year we have

devoted more attention to this, taking a step further and

outlining the current challenges with the denitions and

the 2017 nancial data used in the report, as well as high-

lighting the major progress made in the last 12 months.

In Part Two of the report, 25 prominent guest authors

from outside and inside the UN system present their

ideas and initiatives in concise essays on the nancing

trends impacting the SDGs. The overview to Part Two

on page 66 outlines each of these important perspectives

and contributions. There are some inevitable crossovers

between the issues covered in the papers, but they are

nonetheless clustered into four chapters:

1. Financing the 2030 Agenda: The big picture

2. Earmarking: Making smart choices

3. Financing peacebuilding, humanitarian assistance

and migration: Time to invest

4. Multilateralism on trial?

The 2030 Agenda requires a better understanding of the

complexities and opportunities of nancing development.

Part Two gives us the analysis and insights that we believe

make an important contribution to the debate and to the

choices that lie ahead.

Our overall ambition for this report, which is a collabora-

tive partnership between the Dag Hammarskjöld

Foundation and the UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund Oce,

is to advance the quality of the evidence-based debate

and the marketplace of ideas related to the UN’s role in

nancing development. With a rm platform of data and a

strong portfolio of ideas presented in the report, we hope

that when hard decisions are made – bilateral, multilateral

or other – they deliver on our shared goals.

26

Overview of

United Nations' resource flows

As readers of the Financing the UN Development System

reports have learnt in previous years, the nancial

landscape of the UN is both simple and complex, both

traditional and innovative, both agile and rigid, young

and old. It is a uniting force and a divider. All at the

same time. How and by whom is the UN funded? And

where and on what does the UN spend? The answers to

these questions are key to understanding the multilateral

nancial architecture of the UN and informing future

debates on the funding of the UN.

The rst chapter of Part One is a deep dive into the

nancial engine room of the UN, looking closely at

its revenue streams, where they originate and why

identifying them matters. It also contrasts the funding

of the UN to that of other multilateral institutions.

Chapter Two examines UN expenditure by building up

a global picture of UN operations in nancial terms.

In what functions does the UN invest and where,

geographically, does the UN spend?

Chapter Three discusses the quality of nancial data and

the adoption of new UN data standards. It examines

why these are crucial for our analysis and for correctly

explaining the nancial ecosystem of the UN. It also

scrutinises the nancial data challenges that have been

resolved and what remains to be done.

Finally, Part One explains two new initiatives formally

introduced to the UN in 2019 that will aect how UN

nances are measured, analysed and operationalised:

1) the adoption of the Funding Compact and its

mutual commitments between the UN and its

Member States;

2) the operationalisation of the levy on tightly

earmarked funding and what it entails.

Both are results of the wider UN reform ambitions and

the repositioning of the United Nations development

system (UNDS).¹ The ambition and vision of the

Funding Compact is to measure and strive towards more

exible, predictable and coherent UN funding, while the

levy has been introduced to serve as a nancing

mechanism for the reinvigorated Resident Coordinator

function and to give incentives for more exible funding

to the UN. All these measures are being put in place to

enable the UN to deliver on the ambitions of the 2030

Agenda.

PART ONE

27

Revenue

PART ONE

Chapter One

Assessed

contributions

Voluntary core

contributions

Negotiated

pledges

Earmarked

contributions

Fees

Definition

What is the

central

characteristic

of financing?

How are decisions

on the amount of

contribution made

(burden sharing)?

How are

resources

allocated?

Who takes

allocation

decision?

Fixed amounts,

calculated based on

agreed formula that

Member States

undertake to pay

when signing a

treaty

A price of a

membership

Price is based

on an agreed

formula

Established

in recipient's

budget

UN membership

Voluntary

untied

contributions

Voluntary,

usually annual

contributions

(no earmarking)

Contributions

are purely

voluntary

Established

in recipient's

budget

UN Member

States

Legally binding

contribution

agreements

made by

Member States

Member States

negotiate and

agree on the

contribution each

will make

The amount to

be paid is

negotiated and

legally binding

Established

in recipient's

budget

Recipient

UN entity and

UN Member

States

Voluntary

contributions that

are designated

for a specific

purpose

Funding is

earmarked to

theme, country

or project

No

institutionalised

formula,

contributions are

purely voluntary

Agreed,

case-by-case,

between

contributor and

UN recipient

Specific parties

concerned

Payments

for services

Collection of

separate knowledge,

management and

product fees from

both state and

non-state actors

Flat or

negotiated fees

Various

Various

Total revenue of the UN system

How the UN is nanced aects how it operates and

inuences, for example, the level of exibility and

accountability for the UN entities. Broadly speaking, there

are ve dierent channels of revenue in the UN system:

1) Assessed contributions

2) Voluntary core contributions

3) Negotiated pledges

4) Earmarked contributions

5) Fees

Table 1 outlines the denitions, characteristics, and

burden sharing arrangements, and how decisions are

usually taken in each type of these nancial instruments.

Table 1: The spectrum of UN financing instruments

28

Revenue

Assessed contributions are mandatory membership fees

based on a jointly pre-agreed formula which determines

each member’s fee. For a UN membership, the General

Assembly and the UN Member States determine the

formula for assessed contributions, building on each

Member State’s capacity to pay. Voluntary core

contributions, or what is sometimes referred to as

‘regular resources’, are fully exible non-earmarked

funds. Voluntary core, which is always provided to an

individual UN organisation, is vital for the operations

of many UN entities, but is currently not a revenue

channel for the UN at a system-level. Negotiated pledges

are legally binding commitments, but not a revenue

channel for the UN at a system-level today. An example

of negotiated pledges is the World Bank’s International

Development Association (IDA).

Earmarked contributions are sometimes also referred to

as ‘non-core resources’, or ‘extra budgetary resources’.

These contributions are voluntary for the contributor

but constrained in how they can be used by the recip-

ient, for example, funds can be restricted to a specic

project, theme, region or country. There are many

dierent applications of earmarking, some less stringently

tied, others more tightly earmarked. In 2019, the UN

introduced a 1% levy on tightly earmarked development

funding (for further denitions and applications of the

levy see page 46). Finally, the UN receives revenues from

fees and other revenue streams, linked to public services,

and management and product services.

A deeper look at this category is included further on in

the chapter.

Knowing the denitions helps us in the next step when

looking at the size and mix of these revenue channels

in the UN system for 2017. This is displayed in Figure 1

on the next page which shows that the main channel of

revenue in the UN system is earmarked in some form by

the contributor(s).

In 2017, (the most recent year of available nancial data),

57% of all UN income was earmarked to some degree.

The upward trend in this revenue stream is visible in the

short term; in 2015 and 2016 the share of earmarked

contributions was 54% and 53%, respectively.

The increase of the share of earmarked UN revenue is

part of a long-term trend in UN nancing and forms

part of the changing nancial landscape of the UN

(see Figure 2 on the next page). Figure 2 shows the

distribution over time of the dierent channels of

revenue in the UN system, demonstrating the relative

decline of assessed contributions and voluntary core

contributions combined with the general shift

towards earmarked contributions. Assessed contributions

amounted to 26% in 2017, which was two percentage

points less than in 2016. The voluntary core contribu-

tions decreased by one percentage point to a level of 9%

of the total nancial resources of the UN in 2017.

The remaining revenue stream of 8%, from fees and

other revenues, is steadily rising. Interestingly, the share

of the revenue accrued from these sources almost

equalled the size of the voluntary core contributions in

2017. It is therefore worth taking a closer look at the

types of revenues included in this category. As the word

‘other’ suggests, the category is a broad mix of revenue

streams. It includes fees for management and procure-

ment services as well as nancial revenues accrued from

nancial transactions (interest, foreign exchange gains

etc) and in-kind contributions. In 2017, 70% of the

revenues of this category went to ve UN entities: the

United Nations Oce for Project Services (UNOPS),

the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the

UN Secretariat, the World Food Programme (WFP) and

the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

The almost fully fee-nanced WIPO illustrates an

interesting, although today atypical, UN funding model.

WIPO receives fees for patent services arrangements.

The revenue stream could be characterised as core-like

(as it is presumed to be non-earmarked) even though the

income is likely to uctuate and is tied to a single type

of product – the patent service. WIPO-fees make up

about 9% of the UN’s total revenue in the category of

fees and other revenue. The unique case of WIPO

and other funding models, old and new, are further

elaborated on in Weinlich and Jenks’ article in Part Two

of this report.

29

Revenue

Figure 1: Overview of the total revenue of the UN system by financing instrument, 2017

Source: Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB)

For notes – see page 182.

Earmarked contributions

57%

Assessed contributions

26%

Voluntary core

contributions

9%

Fees and

other revenues

8%

Figure 2: Distribution of total UN system revenue, by financing instrument, 2010–2017

Source: Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB)

For notes – see page 182.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

57%

26%

9%

8%

Assessed contributions

Fees and other revenues

Voluntary core contributions

Earmarked contributions

2016

2014

2012

2017

2015

2013

2011

2010

30

Revenue

Table 2a: Total revenue of the UN system by entity and by financing instrument, 2017

(US$ million)

Source: Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB)

For notes - see page 186.

Entity Assessed

Voluntary

core

Earmarked

Fees and

other revenues

Total

revenue 2017

UN Secretariat

2,578 2,279 623 5,480

CTBTO

119 7 2 128

DPKO

7,853 343 79 8,276

FAO

474 751 39 1,264

IAEA

434 260 8 702

ICAO

80 114 22 216

ICC

167 2 0 170

IFAD

306 104 9 419

ILO

370 293 21 683

IMO

41 7 19 67

IOM

49 15 1,450 100 1,615

ITC

35 29 62 1 127

ITU

125 1 10 47 183

PAHO

102 614 716 1,433

UNAIDS

173 52 8 233

UNCDF

10 47 3 60

UNDP

647 4,245 344 5,236

UNEP

199 443 25 668

UNESCO

316 261 71 648

UNFCCC