2022 SPECIAL REPORT

New threats to human security

in the Anthropocene

Demanding greater solidarity

New threats to human security in the Anthropocene

Demanding greater solidarity

Copyright @ 2022

By the United Nations Development Programme

1 UN Plaza, New York, NY 10017 USA

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without

prior permission.

General disclaimers. The designations employed and the presentation

of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any

opinion whatsoever on the part of the Human Development Report

Office (HDRO) of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its

authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines

for which there may not be full agreement.

The findings, analysis, and recommendations of this Special Report

do not represent the official position of the UNDP or of any of the UN

Member States that are part of its Executive Board. They are also not

necessarily endorsed by those mentioned in the acknowledgments or

cited.

The mention of specific companies does not imply that they are

endorsed or recommended by UNDP in preference to others of a similar

nature that are not mentioned.

Some of the figures included in the analytical part of the report where

indicated have been estimated by the HDRO or other contributors to the

Report and are not necessarily the official statistics of the concerned

country, area, or territory, which may use alternative methods. The

published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind,

either expressed or implied.

The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with

the reader. In no event shall the HDRO and UNDP be liable for damages

arising from its use.

Additional resources related to the Report can be found online at

http://hdr.undp.org. Resources on the website include digital versions

and translations of the Report and the overview, an interactive web

version of the Report. Corrections and addenda are also available

online.

New threats to

human security in the

Anthropocene

Demanding greater solidarity

SPECIAL REPORT 2022

Empowered lives.

Resilient nations.

SPECIAL REPORT 2022

Team

The report was prepared by a team led by Heriberto Tapia under the

guidance of Pedro Conceição. The core team was composed of Ricardo

Fuentes-Nieva, Moumita Ghorai, Yu-Chieh Hsu, Admir Jahic, Christina

Lengfelder, Rehana Mohammed, Tanni Mukhopadhyay, Shivani Nayyar,

Camila Olate, Josefin Pasanen, Fernanda Pavez Esbry, Mihail Peleah and

Carolina Rivera Vázquez. Communications, operations, and research and

production support were provided by Dayana Benny, Allison Bostrom,

Mriga Chowdhary, Maximilian Feichtner, Rezarta Godo, Jonathan Hall,

Seockhwan Bryce Hwang, Fe Juarez Shanahan, Chin Shian Lee, Jeremy

Marand, Sarantuya Mend, Stephen Sepaniak, Anupama Shroff, Marium

Soomro and I Younan An.

The High-Level Advisory Panel of Eminent Experts provided support and

guidance: Laura Chinchilla and Keizo Takemi (co-chairs), Amat Al Alim

Alsoswa, Kaushik Basu, Abdoulaye Mar Dieye, Ilwad Elman, María Fernanda

Espinosa Garcés, Haishan Fu, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, Amy Jadesimi, Jennifer

Leaning and Belinda Reyers.

ii NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

We are faced with a development paradox. Even though

people are on average living longer, healthier and wealthier

lives, these advances have not succeeded in increasing peo-

ple’s sense of security. This holds true for countries all around

the world and was taking hold even before the uncertainty

wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic has increased this uncertainty. It has imper-

iled every dimension of our wellbeing and amplified a sense

of fear across the globe. This, in tandem with rising geopo-

litical tensions, growing inequalities, democratic backsliding

and devastating climate change-related weather events,

threatens to reverse decades of development gains, throw

progress on the Sustainable Development Goals even fur-

ther off track, and delay the urgent need for a greener, more

inclusive and just transition.

Against this backdrop, I welcome the Special Report

on New threats to human security in the Anthropocene:

Demanding greater solidarity, produced by the United

Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The report

explains this paradox, highlighting the strong association

between declining levels of trust and increased feelings of

insecurity.

It suggests that during the Anthropocene—a term pro-

posed to describe the era in which humans have become

central drivers of planetary change, radically altering the

earth’s biosphere—people have good reason to feel inse-

cure. Multiple threats from COVID-19, digital technology,

climate change, and biodiversity loss, have become more

prominent or taken new forms in recent years.

In short, humankind is making the world an increasingly

insecure and precarious place. The report links these new

threats with the disconnect between people and planet,

arguing that they—like the Anthropocene itself—are deeply

entwined with increasing planetary pressure.

The contribution of this report is to update the concept

of human security to reflect this new reality. This implies

moving beyond considering the security of individuals and

communities, to also consider the interdependence among

people, and between people and planet, as reflected in the

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

In doing so, the report offers a way forward to tackle to-

day’s interconnected threats. First, by pursuing human secu-

rity strategies that affirm the importance of solidarity, since

we are all vulnerable to the unprecedented process of plan-

etary change we are experiencing during the Anthropocene.

And second, by treating people not as helpless patients, but

agents of change and action capable of shaping their own

futures and course correcting.

The findings in the report echo some of the key themes

in my report on Our Common Agenda, including the impor-

tance of investing in prevention and resilience, the protection

of our planet, and rebuilding equity and trust at a global

scale through solidarity and a renewed social contract.

The United Nations offers a natural platform to advance

these core objectives with the involvement of all relevant

stakeholders. This report offers valuable insights and analy-

ses, and I commend it to a wide global audience as we strive

to advance Our Common Agenda and to use the concept of

human security as a tool to accelerate the achievement of

the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

António Guterres

Secretary-General

United Nations

Foreword

iiiFOREWORD

Acknowledgements

This Report builds on cumulative contributions over close

to three decades that started with the seminal 1994 Human

Development Report (led by Mahbub ul Haq), which popu-

larized the concept of human security, continuing with the

groundbreaking work of the Human Security Commission,

led by Sadako Ogata and Amartya Sen, published in 2003.

The preparation of this Report would not have been pos-

sible without the support, ideas and advice from numerous

individuals and organizations.

The Report benefited deeply from the intellectual advice,

guidance and continuous encouragement provided by

the High-Level Advisory Panel of Eminent Experts. We are

particularly grateful to Co-Chairs Laura Chinchilla and Keizo

Takemi for their intellectual leadership, commitment and

hard work through countless sessions (virtual, hybrid and in

person) throughout 2021. The other members of the Advisory

Board were Amat Al Alim Alsoswa, Kaushik Basu, Abdoulaye

Mar Dieye, Ilwad Elman, María Fernanda Espinosa Garcés,

Haishan Fu, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, Amy Jadesimi, Jennifer

Leaning and Belinda Reyers.

We are grateful to the participants of the virtual sympo-

sium, A New Generation of Human Security, held 8–11 June

2021, including Vaqar Ahmed, Michael Barnett, Lincoln C.

Chen, Alison Fahey, Andreas Feldmann, James Foster, Des

Gasper

*

, Rachel Gisselquist, Anne-Marie Goetz, Oscar A.

Gómez

*†

, Toshiya Hoshino

*†

, Mary Kaldor, Raúl Katz, Erika

Kraemer-Mbula, Staffan Lindberg, Koji Makino

†

, Vivienne

Ming, Joana Monteiro, Toby Ord, Racha Ramadan, Uma

Rani

†

, Pablo Ruiz Hiebra, Siri Aas Rustad

*

, Joaquin Salido

Marcos, Anne-Marie Slaughter, Dan Smith, Frances Stewart,

Shahrbanou Tadjbakhsh

†

, Tildy Stokes, Yukio Takasu, Am-

brose Otau Talisuna and Shen Xiaomeng.

We are thankful for especially close collaborations with

our partners: the Climate Impact Lab (a consortium formed

by the University of California, Berkeley; the Energy Policy In-

stitute at the University of Chicago; the Rhodium Group; and

Rutgers University), the Human Development and Capability

Association, the International Labour Organization, the Ja-

pan International Cooperation Agency, the Migration Policy

* Also author of a background paper.

† Also a peer reviewer.

Institute, the Peace Research Institute Oslo, the Stockholm

International Peace Research Institute, the United Nations

Children’s Fund, the United Nations Human Security Unit, the

United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation and the

World Bank Group.

We also extended our appreciation for all the data, writ-

ten inputs, background papers and peer reviews of draft

chapters to the Report, including those by Faisal Abbas,

Enrico Calandro, Cedric de Coning, Andrew Crabtree,

Karen Eggleston, Erle C. Ellis, Andreas Feldman, Juliana de

Paula Filleti, Pamina Firchow, Rana Gautam, Jose Gómez,

Daniela S. Gorayeb, Martin Hilbert, Daniel M. Hofling, Flo-

rian Krampe, Martin Medina, John Morrissey, Ryutaro Mu-

rotani, Ilwa Nuzul Rahma, Ilse Oosterlaken, Monika Peruffo,

Thomas Probert, Sanjana Ravi, Diego Sánchez-Ancochea,

Tobias Schillings, Parita Shah, Amrikha Singh, Mirjana

Stankovic, Behnam Taebi, Jeroen Van Den Hoven and Yuko

Yokoi.

Several virtual consultations with thematic and regional

experts were held between October and December 2021.

We are grateful for inputs during these consultations. Further

support was also extended by others too numerous to men-

tion here. Consultations are listed at http://hdr.undp.org/en/

new-gen-human-security. Contributions, support and assis-

tance from partnering institutions, including UNDP regional

bureaus and country offices, are also acknowledged with

much gratitude.

Our deep appreciation to Hajime Kishimori and Hiroshi

Kuwata for their strategic and logistical support throughout

the process leading to this Report. Many UNDP colleagues

provided advice, support for consultations and encourage-

ment. We are grateful to Ludo Bok, Khalida Bouzar, Cecilia

Calderón, Michele Candotti, Christine Chan, Joseph D’Cruz,

Mandeep Dhaliwal, Keiko Egusa, Almudena Fernández,

Ayako Hatano, Tatsuya Hayase, Boyan Konstantinov, Raquel

Lagunas

†

, Luis Felipe López-Calva, Tasneem Mirza, Ulrika

Modeer, Paola Pagliani, Maria Nathalia Ramirez, Noella Rich-

ard, Isabel Saint Malo, Ben Slay, Mirjana Spoljaric Egger, Ma-

ria Stage, Bishwa Tiwari, Hisae Toyoshima, Swarnim Wagle,

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v

Kanni Wignaraja, Lesley Wright, Yoko Yoshihara and Yan-

chun Zhang.

The preparation of this Report is part of the work lead-

ing to the 2021/2022 Human Development Report. The

Human Development Report Office extends its sincere

gratitude for the financial contributions from the Govern-

ment of Japan, the Republic of Korea and the Government

of Sweden.

We are grateful for the highly professional work of Stronger

Stories on strategic narratives and of the editors and layout

artists at Communications Development Incorporated —

led by Bruce Ross-Larson with Joe Caponio, Mike Crumplar,

Christopher Trott and Elaine Wilson. A special word of

gratitude to Bruce, who brought unparalleled scrutiny and

wisdom — and a bridge to history, as the editor of both the

1994 Human Development Report and the 2003 Ogata-Sen

report.

To conclude, we are extremely grateful to UNDP Admini-

strator Achim Steiner, for giving us the space, encourage-

ment and support to write this report on human security and

for pushing us to make sense of the insecurities faced by

people everywhere in our interconnected planet, which we

hope will help set the foundations for a new generation of

human security strategies.

Pedro Conceição

Director

Human Development Report Office

vi NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

Contents

Foreword iii

Acknowledgements v

Overview 1

PART I

Expanding human security through greater solidarity in the

Anthropocene 9

CHAPTER 1

Human security: Apermanent and universal imperative 11

Becoming richer amid a vast sea of human insecurity 15

Towards human security through the “eyes of humankind” 24

Annex 1.1. A brief account of the origins, achievements and

challenges of the human security concept 34

Annex 1.2. The Index of Perceived Human Insecurity 38

CHAPTER 2

The Anthropocene context is reshaping human security 43

The self-reinforcing interaction between dangerous planetary

changes and social imbalances 46

Compounding threats to human security 50

Human security in the Anthropocene context 58

PART II

Tackling a new generation of threats to human security 63

CHAPTER 3

Digital technology’s threats to human security 65

Cyberinsecurity and unintended consequences of technology 67

Upholding human rights in addressing harms on social media 68

Artificial intelligence–based decisionmaking can undermine

human security 70

Uneven access to technological innovation 73

CHAPTER 4

Unearthing the human dimension of violentconflict 77

Systemic interaction of conflict with threats to human security

calls for systemic responses 79

Agency connects empowerment and protection for peaceful lives 83

The dynamics of violent conflict are evolving under the new

generation of human security threats 83

Putting people at the heart of conflict analysis, conflict

prevention and sustaining peace shows the power of the

human security approach 87

CHAPTER 5

Inequalities and the assault on human dignity 91

Horizontal inequalities undermine human dignity 93

Threats to human security along the lifecycle 94

Violence and economic discriminations harm the human

security of women and girls 98

Inequalities in power across race and ethnicity hurt everyone’s

human security 100

People on the move can be forced to follow paths of human

insecurity 102

Ending discrimination against different expressions,

behaviours or bodies enhances human security for all 105

Eliminating horizontal inequalities to advance human security:

The salience of agency and the imperative of solidarity 107

CHAPTER 6

Healthcare systems outmatched by new human security

challenges 117

As economies bounce back from the Covid-19 pandemic,

people’s health remains under threat 120

An evolving disease burden is driving adjustments to

healthcare systems 123

Reinforcing human security though enhanced healthcare

systems 125

Strategies to enhance human security based on solidarity:

Towards the new generation of universalism in healthcare

systems 128

Annex 6.1. The Healthcare Universalism Index: Coverage,

equity and generosity 136

CONCLUSION

Greater solidarity: Towards human development with

humansecurity 139

Notes 144

References 155

BOXES

1.1 The Covid-19 pandemic as a deep human security crisis

continues into 2022 13

1.2 Trust’s many faces 19

1.3 Agency in policy design: An example of participatory

development 26

1.4 Human security and the Sustainable Development Goals 32

2.1 Human security for a more-than-human world 45

2.2 Biodiversity loss, food security and disaster risk reduction 53

3.1 Estonia’s e-governance: Technology follows values 69

CONTENTS vii

3.2 Facial recognition technology: dangerous and largely unregulated 71

4.1 Adaptive peacebuilding: Insights from complexity theory

for strengthening the resilience and sustainability of social-

ecological systems 81

4.2 Social protests have intensified over the past three years 86

4.3 Measuring conflict-affected populations 88

4.4 Everyday Peace Indicators 90

5.1 Femicide: The killing of women and girls because of their gender 101

5.2 Understanding transfemicide 106

6.1 The mental health crisis is a human security emergency 124

6.2 From global institutional weakness to the last pandemic 134

FIGURES

1 Perceptions of human insecurity are widespread worldwide 4

2 The Covid-19 pandemic has caused an unprecedented decline

in Human Development Index values 5

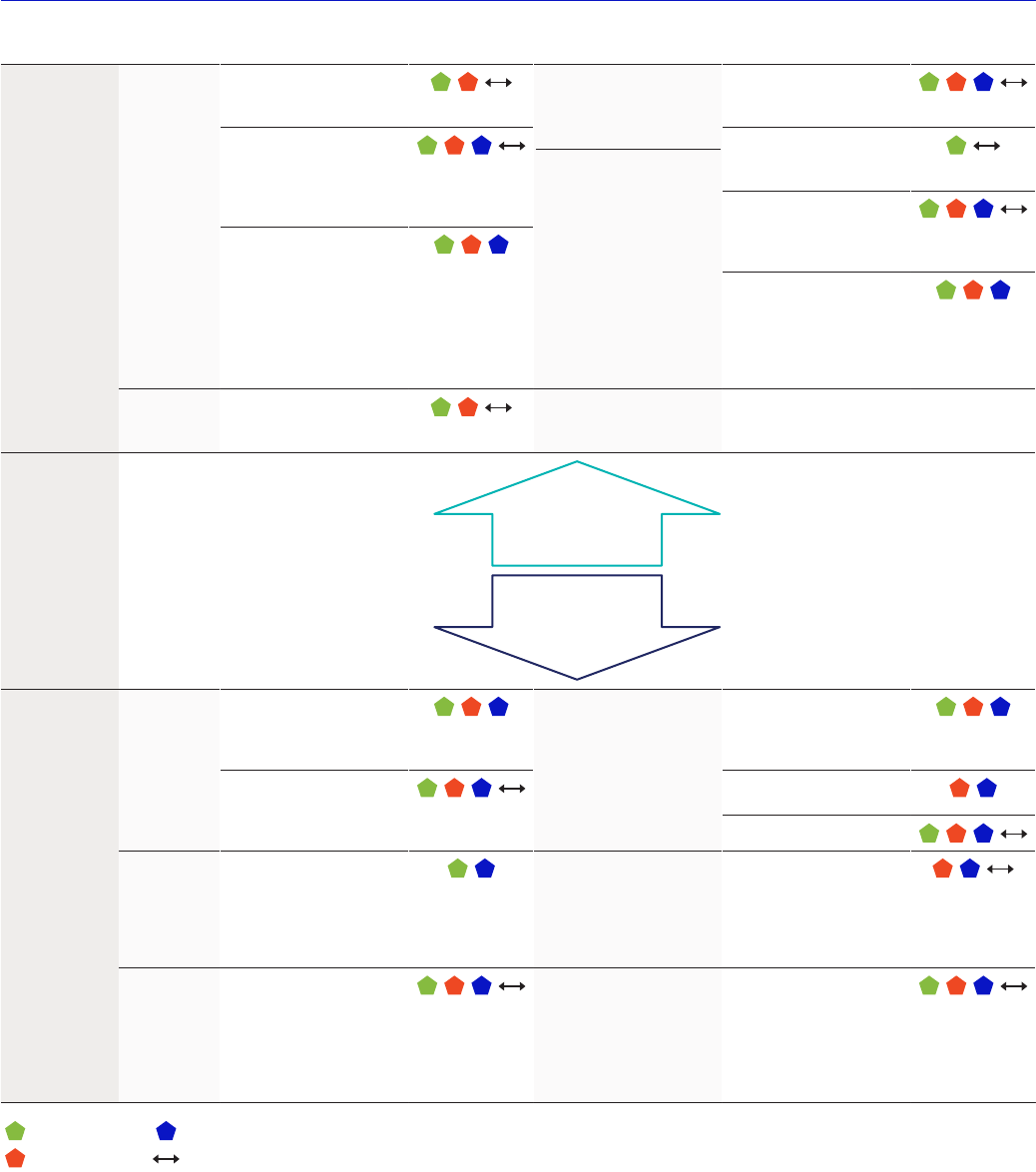

3 The new generation of human security threats 6

4 Enriching human security for the Anthropocene 7

1.1 Even in very high Human Development Index countries, less

than a quarter of people feel secure 17

1.2 Human insecurity tends to be higher in countries with lower

Human Development Index values 17

1.3 Human insecurity is increasing in most countries— and surging

in some very high Human Development Index countries 18

1.4 Where human security is higher, trust tends to be higher,

regardless of satisfaction with one’s financial situation 18

1.5 A new generation of threats to human security is playing out

in the unprecedented context of the Anthropocene 21

1.6 Higher Human Development Index values have come with

higher planetary pressures 22

1.7 Nonstate conflict fatalities have been increasing in high

Human Development Index countries 23

1.8 The virtuous cycle of agency, empowerment and protection 27

1.9 Advancing human security in the Anthropocene context:

Adding solidarity to protection and empowerment 30

2.1 The Anthropocene context is reshaping human security

through the interaction of dangerous planetary changes and

social imbalances 46

2.2 The destabilizing dynamic of climate change: More developed

countries tend to capture more benefits from planetary

pressures and less of their costs 48

2.3 Increasing asymmetries—net lives saved by mitigation 49

2.4 The distribution of mortality risks caused by climate change is

expected to be unequal between and within countries 50

2.5 A large fraction of the population facing water shortage lives

in subnational territories with low Human Development Index

values and high gender inequality 51

2.6 Hunger and food insecurity are on the rise 52

2.7 In a very high emissions scenario some regions of the world

might face climate change–induced mortality rates similar to

those of the main causes of deaths today 54

2.8 The Anthropocene context affects forced internal displacements 56

2.9 Climate change is expected to affect’s people ability to work 57

3.1 Digital labour platforms are growing 72

3.2 Covid-19 vaccine-related patents are concentrated in just a

few countries 74

4.1 Violent conflict is increasing in parallel with progress in human

development 79

4.2 The number of violent conflicts is rising again 87

4.3 The number of forcibly displaced people is at a record high 89

5.1 Different groups of people experience new threats to human

security differently 95

5.2 The change in functional capacity over the lifecycle has

different implications for human security challenges and thus

requires different policies 96

5.3 There is great inequality between high-income and low-

income countries in young people’s internet access at home 96

5.4 Different forms of violence against women and girls: Linking

the iceberg model to the violence triangle 100

5.5 Migration and displacement on a path of insecurity 103

5.6 Black women have higher unemployment rates in Brazil and

South Africa, first quarter of 2021 107

5.7 Building blocks to advance human security by reducing

horizontal inequalities 108

S5.2.1 A new generation of human security threats for children 113

6.1 The global economy is recovering, but people’s health is not 121

6.2 The disparities in Covid-19 vaccination across countries are stark 122

6.3 More people are dying from noncommunicable diseases

today than in the past 123

6.4 Progress with inequality: Widening gaps in healthcare over time 130

6.5 There is a strong negative association between Healthcare

Universalism Index value and child probability of death up to

an index value of around 0.6 130

6.6 At a Healthcare Universalism Index value of about 0.4 and

higher, the probability of death at ages 50–80 drops quickly

as index value increases 131

6.7 As Healthcare Universalism Index value increases

from 0.5, there is a strong relationship between it and

noncommunicable disease–related deaths 131

6.8 Up to a value of about 0.4, Healthcare Universalism Index value

is not associated with Global Health Security Index value, but

above that level, the relationship is strongly positive and significant 132

6.9 The greatest threats to human security in the Anthropocene

context are likely to be experienced where Healthcare

Universalism Index values are lower 132

A6.1 Dimensions and indicators used to calculate the Healthcare

Universalism Index 136

SPOTLIGHTS

1.1 Exploring how the human security approach can illuminate

the overlaps between the response to Covid-19 pandemic and

climate change 40

5.1 A feminist perspective on the concept of human security 110

5.2 Children and human security 113

TABLES

1.1 Evolution of the action framework for human security in the

Anthropocene context 31

A1.2.1 Dimensions and subdimensions of the Index of Perceived

Human Insecurity 38

S1.1 Promoting empowerment, protection and solidarity in a world

of interconnected threats: Example 41

5.1 Number of people age 65 or older, by geographic region, 2019

and 2050 97

A6.1 Limits of the generosity and equity indices 137

viii NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

OVERVIEW

New threats to

human security in

the Anthropocene:

Demanding greater

solidarity

2 NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

OVERVIEW

New threats to human security in the Anthropocene:

Demanding greater solidarity

As the Covid-19 pandemic got under way, the world

had been reaching unprecedented heights on the

Human Development Index (HDI). People were, on

average, living healthier, wealthier and better lives

for longer than ever. But under the surface a growing

sense of insecurity had been taking root. An estimat-

ed six of every seven people across the world already

felt insecure in the years leading up to the pandemic

(gure 1). And this feeling of insecurity was not only

high — it had been growing in most countries with

data, including a surge in some countries with the

highest HDI values.

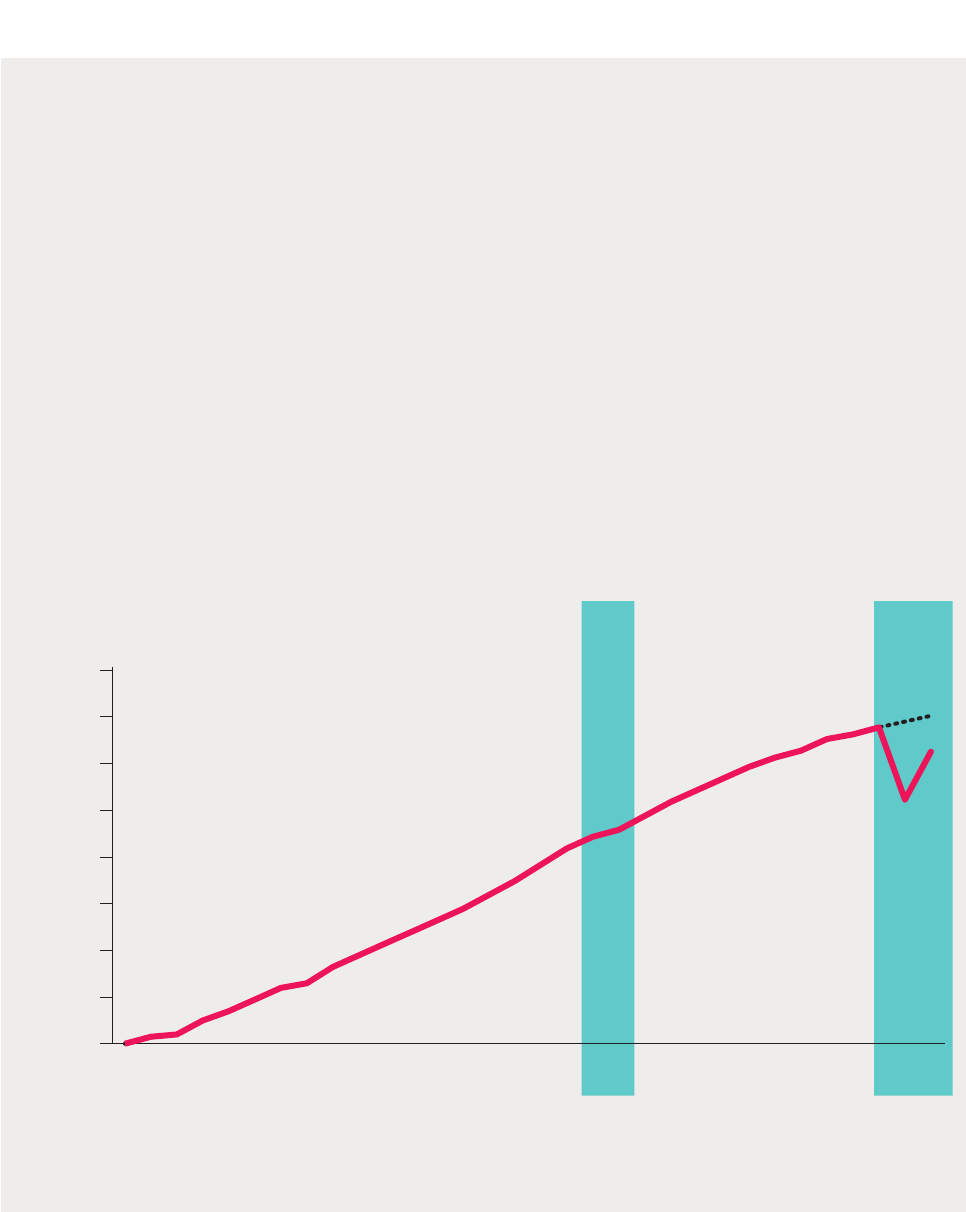

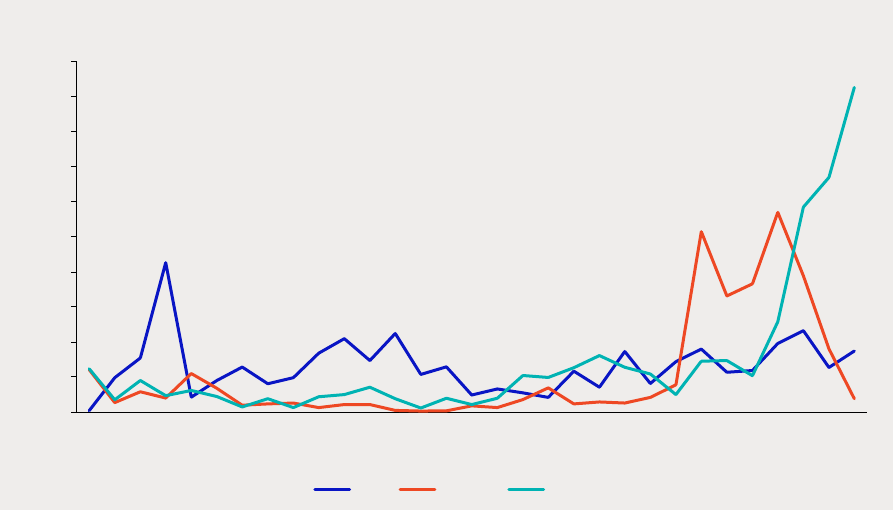

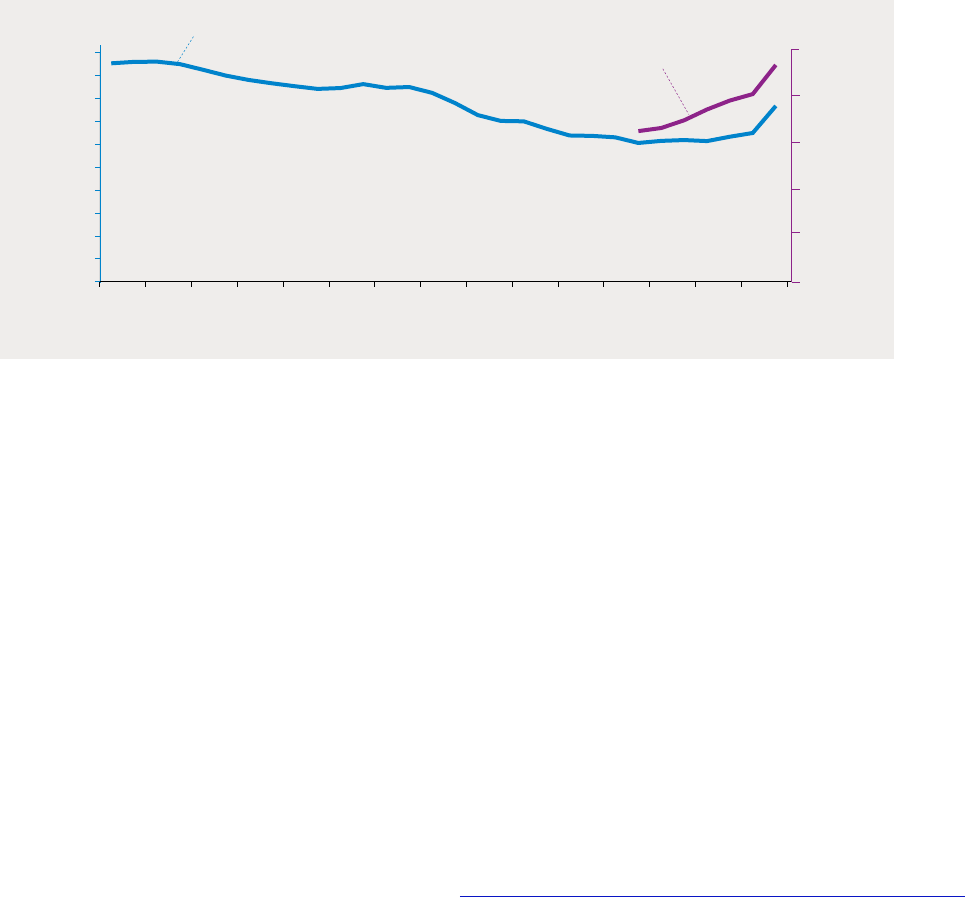

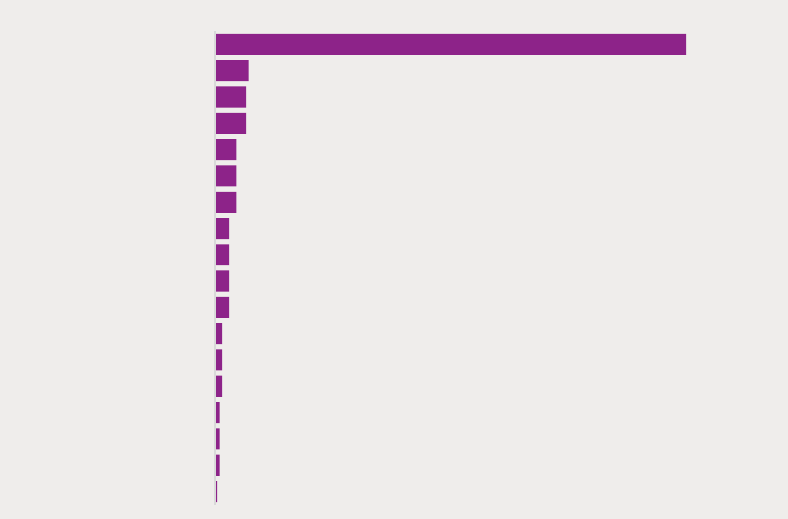

The Covid-19 pandemic has now aected every-

one, imperilling every dimension of our wellbeing

and injecting an acute sense of fear across the globe.

For the rst time, indicators of human development

have declined — drastically, unlike anything experi-

enced in other recent global crises. The pandemic

has infected and killed millions of people worldwide.

It has upended the global economy, interrupted ed-

ucation dreams, delayed the administration of vac-

cines and medical treatment and disrupted lives and

livelihoods. In 2021, even with the availability of very

unequally distributed Covid-19 vaccines, the eco-

nomic recovery that started in many countries and

the partial return to schools, the crisis deepened in

health, with a drop in life expectancy at birth. And the

HDI, adjusted for Covid-19, had yet to recover about

ve years of progress, according to new simulations

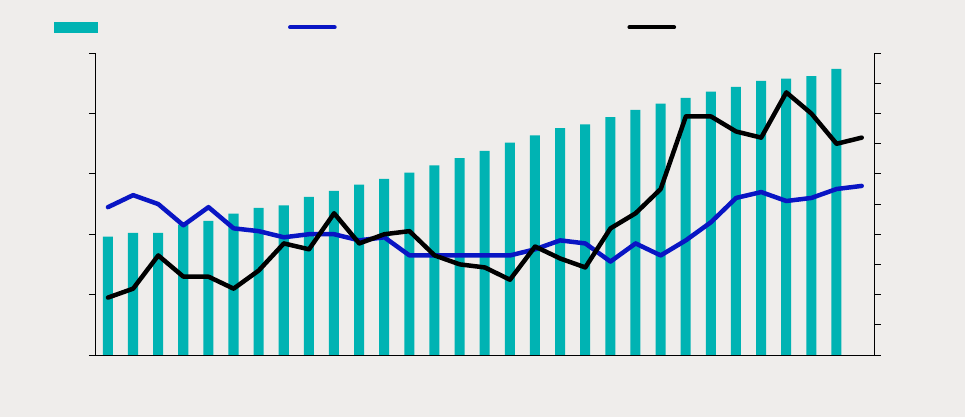

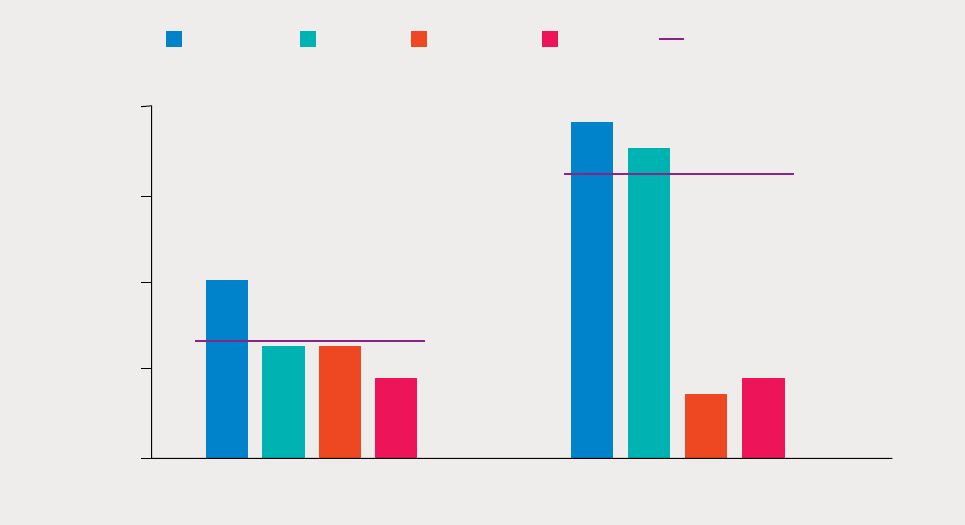

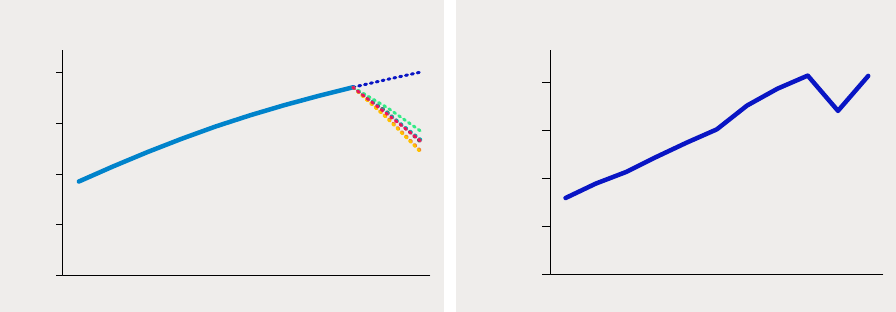

(gure 2).

It is not hard to understand how Covid-19 has

made people feel more insecure. But what accounts

for the startling bifurcation between improvements

in wellbeing achievements and declines in people’s

perception of security? That is the motivating ques-

tion for this Report. In addressing it, we hope to avoid

returning to pathways of human development with

human insecurity.

In the background of the human development–

human security disconnect looms the Anthropocene,

the age of humans disrupting planetary processes.

Development approaches with a strong focus on eco-

nomic growth and much less attention to equitable

human development have produced stark and grow-

ing inequalities and destabilizing and dangerous

planetary change. Climate change is an example, and

Covid-19 may very well be. The 2020 Human Devel-

opment Report showed that no country has achieved

a very high HDI value without contributing heavily

to pressures driving dangerous planetary change. In

addition to climate change and more frequent dis-

ease outbreaks that are linked to planetary pressures,

we confront biodiversity losses and threats to key

ecosystems, from tropical forests to the oceans. Our

pursuit of development has neglected our embedded-

ness in nature, leading to new threats as a by-product

of development: new health threats, increased food

insecurity and more frequent disasters, among many

others. Recognizing that our development patterns

drive human insecurity forces us to revisit the human

security concept and understand what it implies for

the Anthropocene.

When introduced in 1994, the human security ap-

proach refocused the security debate from territori-

al security to people’s security. This idea, which the

UN General Assembly endorsed in 2012, invited se-

curity scholars and policymakers to look beyond pro-

tecting the nation-state to protecting what we care

most about in our lives: our basic needs, our physical

integrity, our human dignity. It emphasized the im-

portance of everyone’s right to freedom from fear,

freedom from want and freedom from indignity. It

highlighted the close connection among security, de-

velopment and the protection and empowerment of

individuals and communities. This Report explores

how the new generation of interacting threats, play-

ing out in the Anthropocene context, aect human

security and what to do about it.

Part I of the Report shows how the human security

concept helps identify blind spots when development

is assessed simply by measuring achievements in

wellbeing and suggests ways to enrich the human se-

curity frame to account for the unprecedented chal-

lenges of the Anthropocene context. Part II discusses

four threats to human security that are superimposed

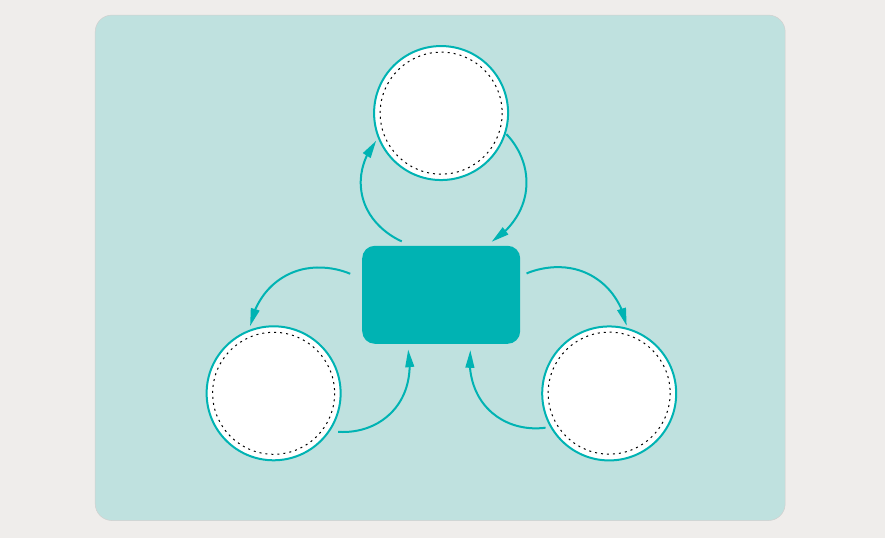

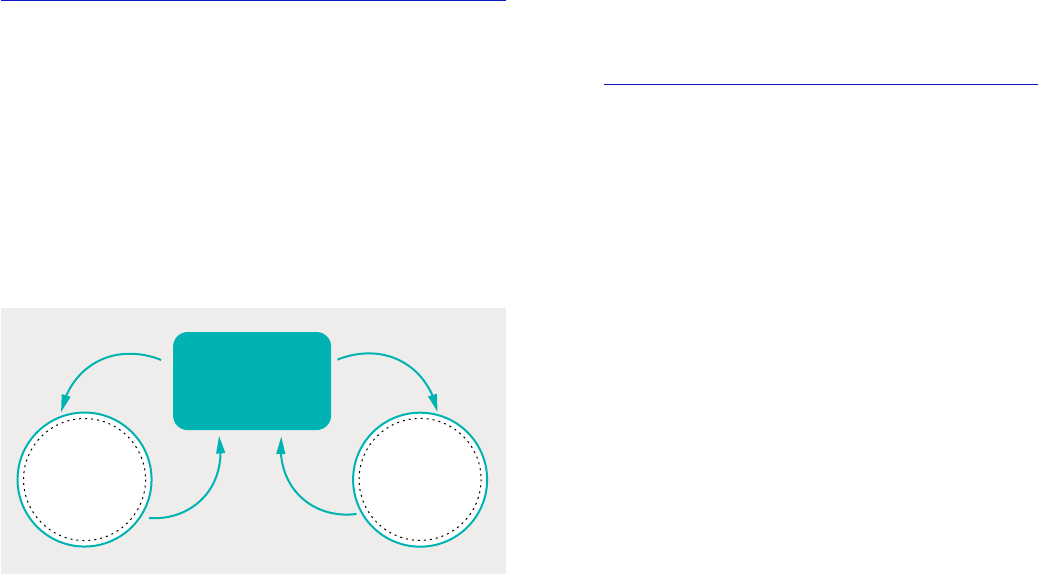

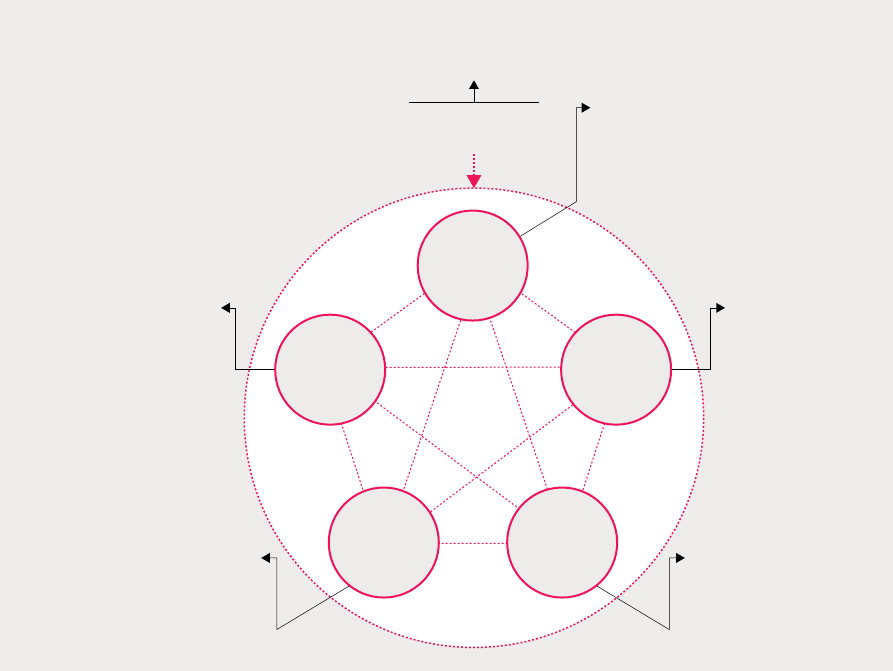

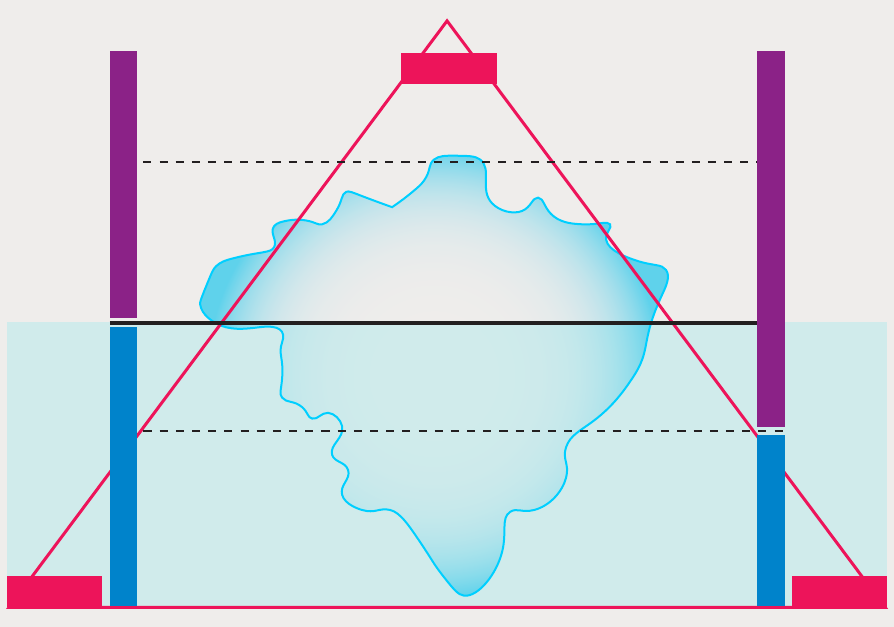

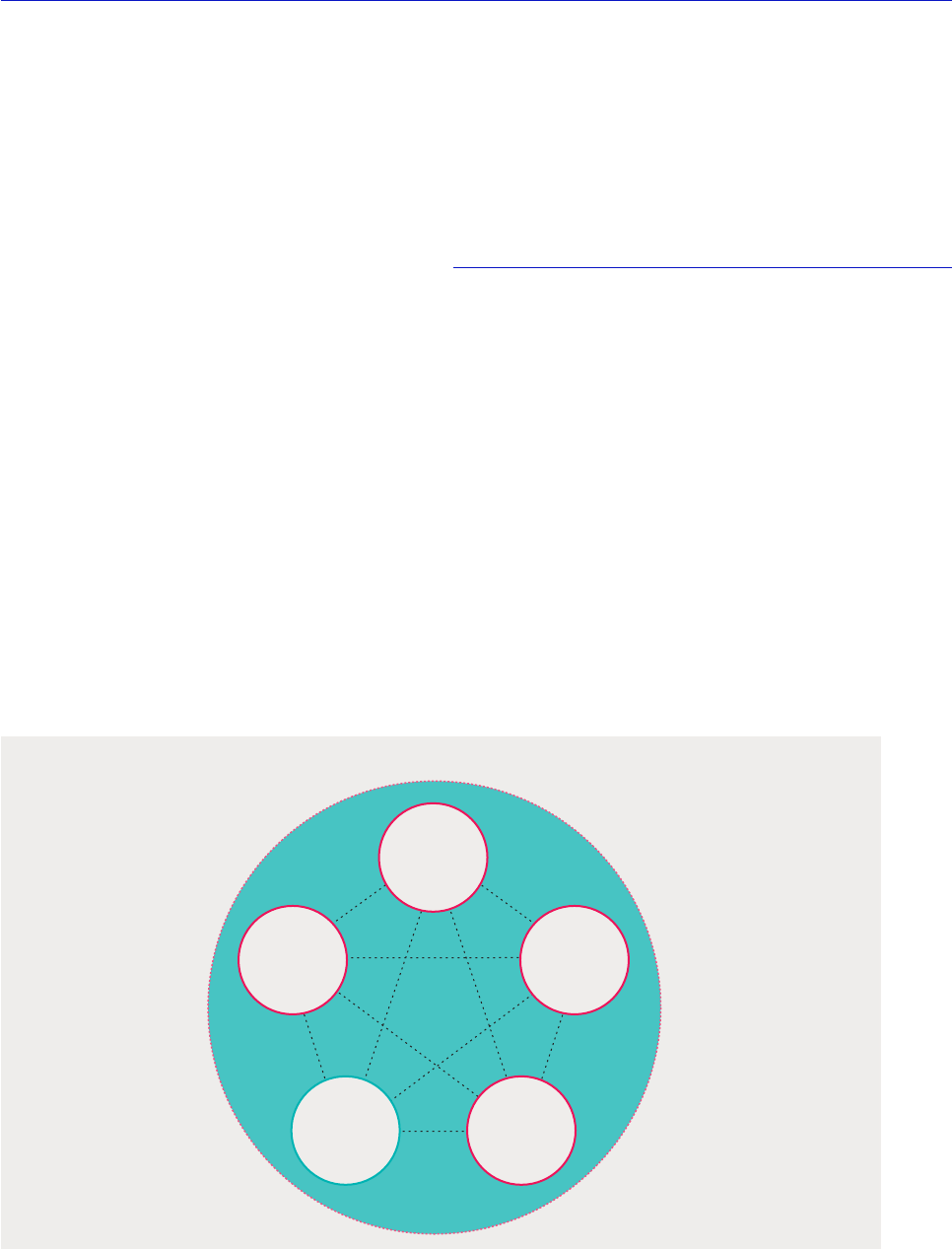

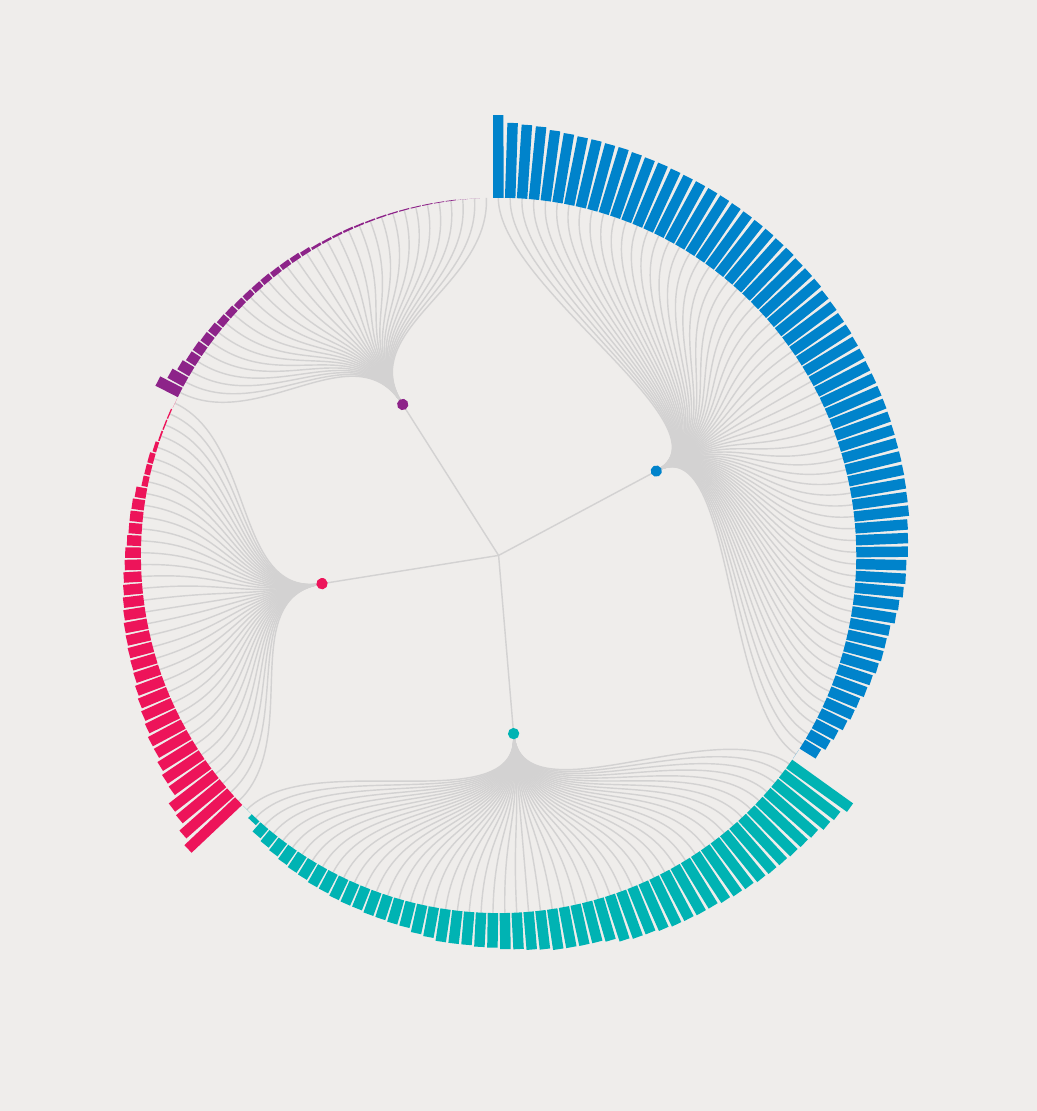

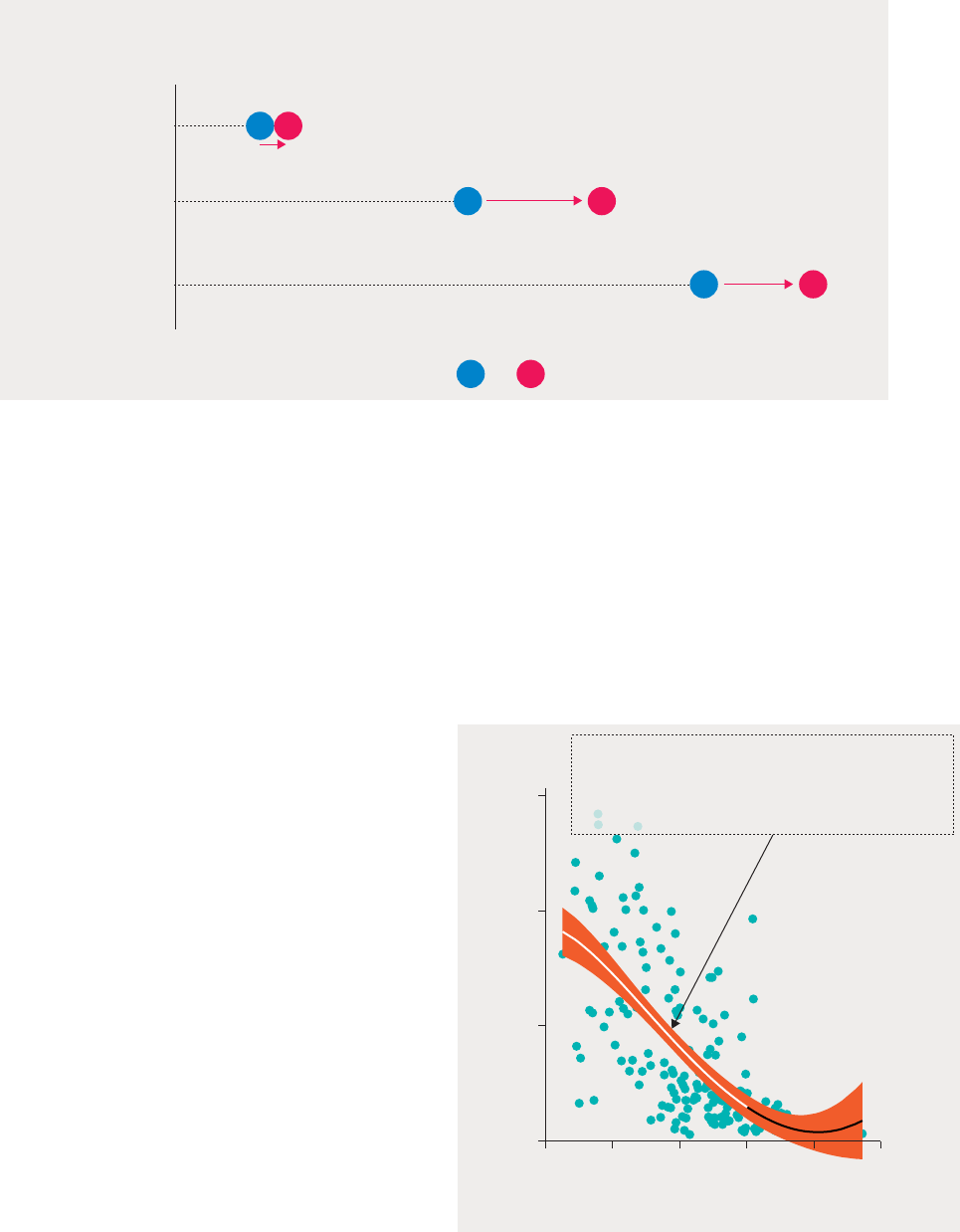

on the Anthropocene context (gure 3): the down-

sides of digital technology, violent conict, horizon-

tal inequalities, and evolving challenges to healthcare

systems. While the underlying challenge of each

threat taken individually is not new, the threats are

novel in the expression that they acquire in the An-

thropocene context and their interlinked nature,

which has been building over time. Current develop-

ment journeys have often missed that point, focusing

on addressing problems in silos when designing or

evaluating policy.

OVERVIEW 3

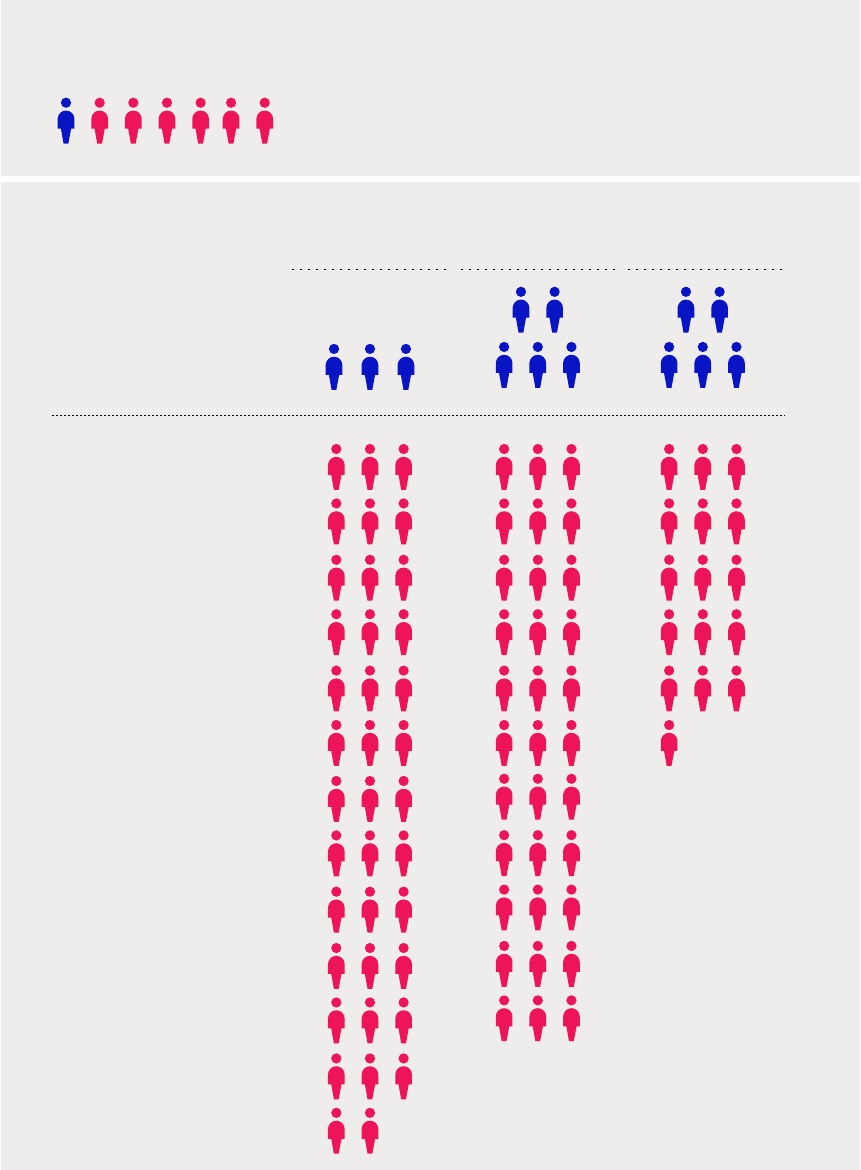

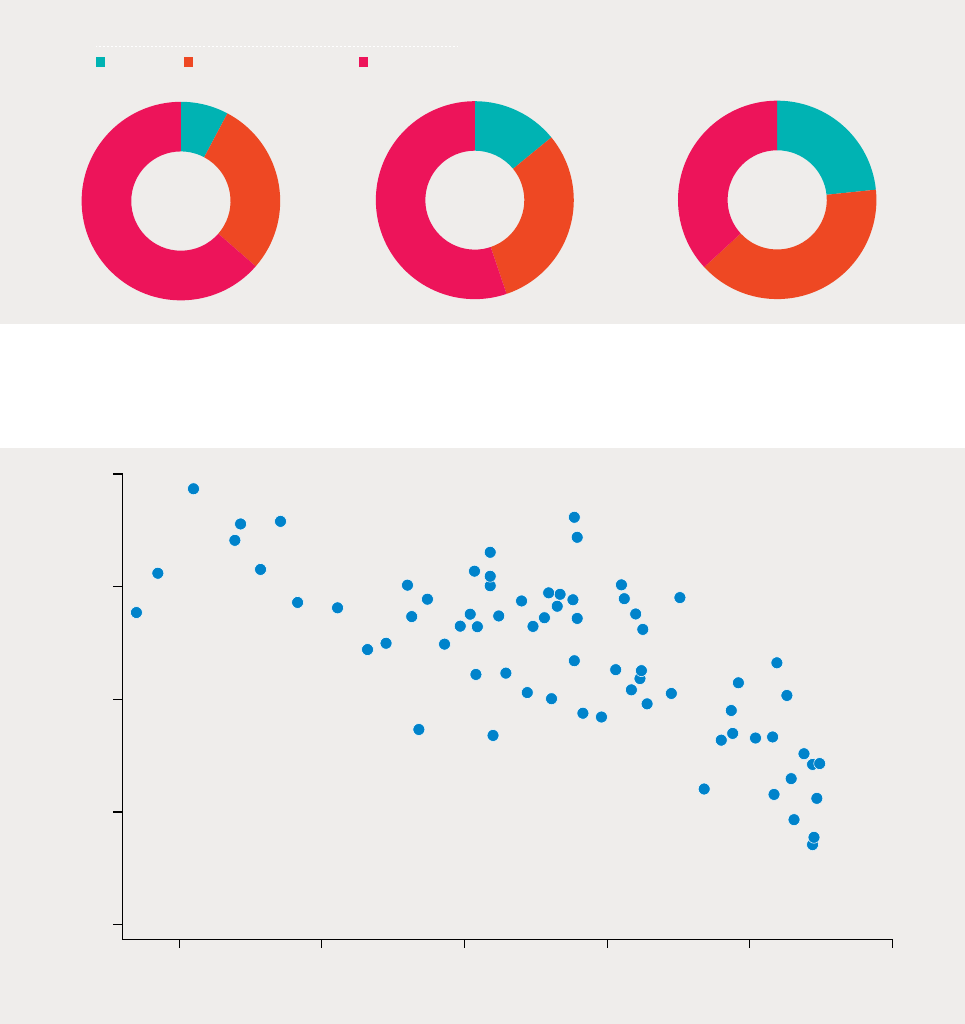

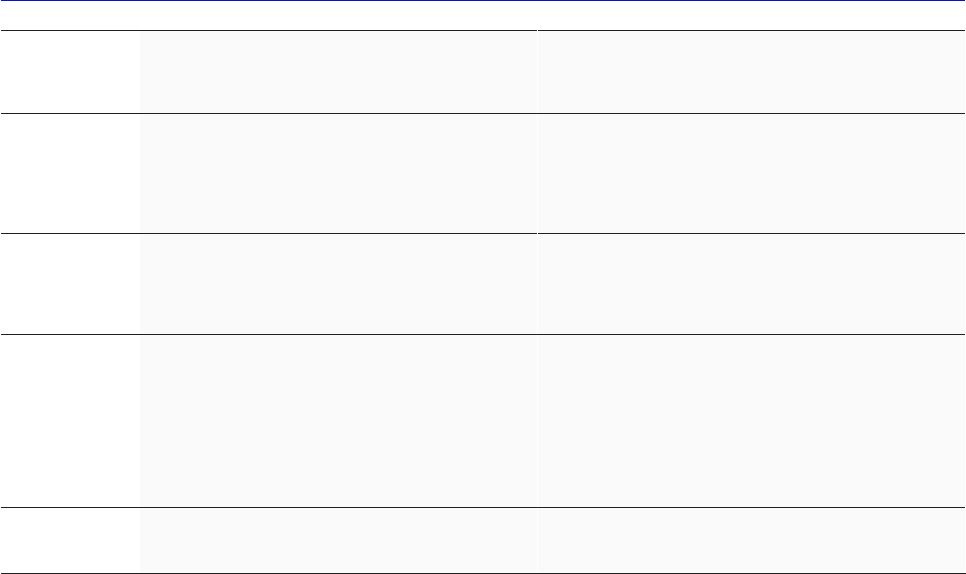

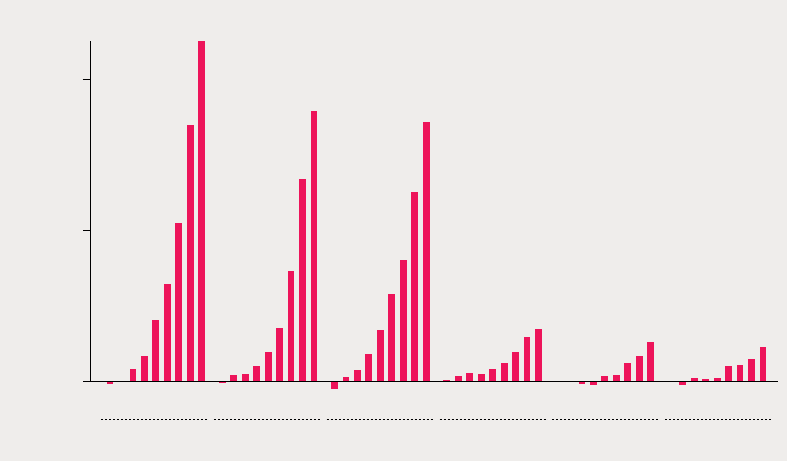

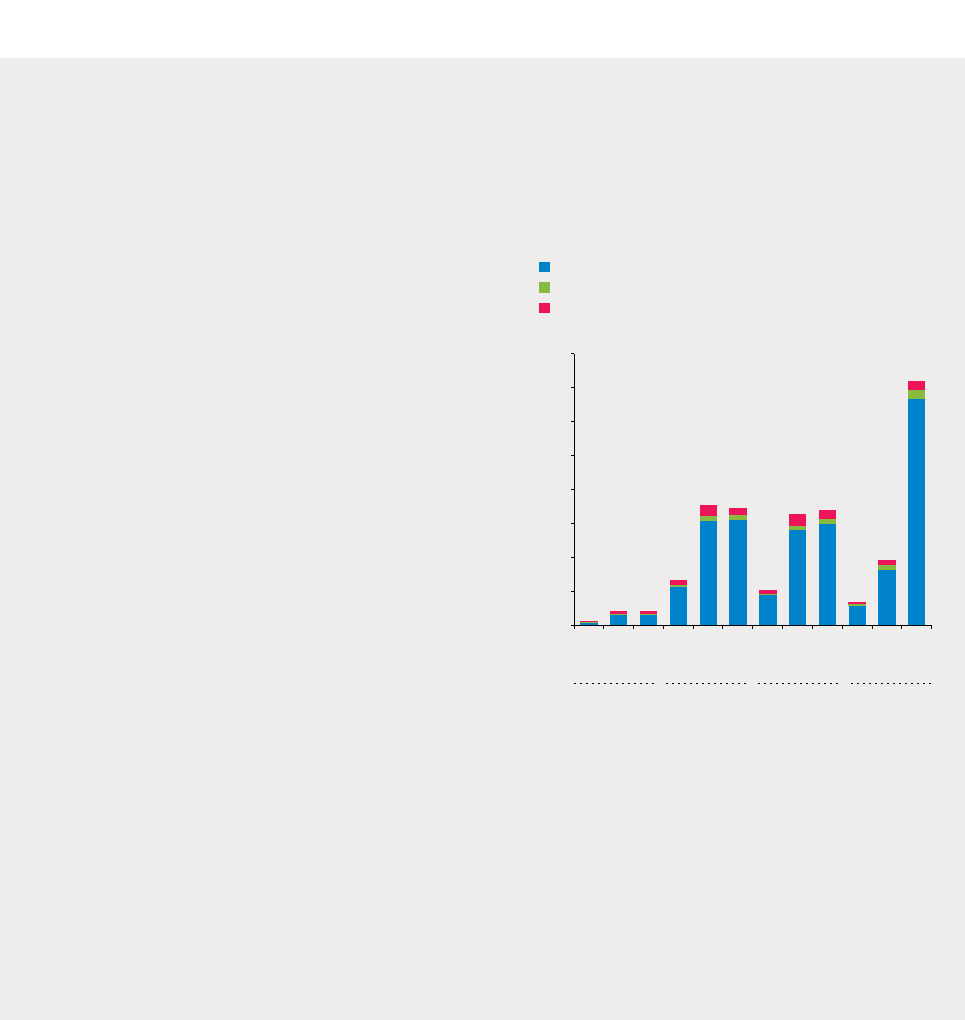

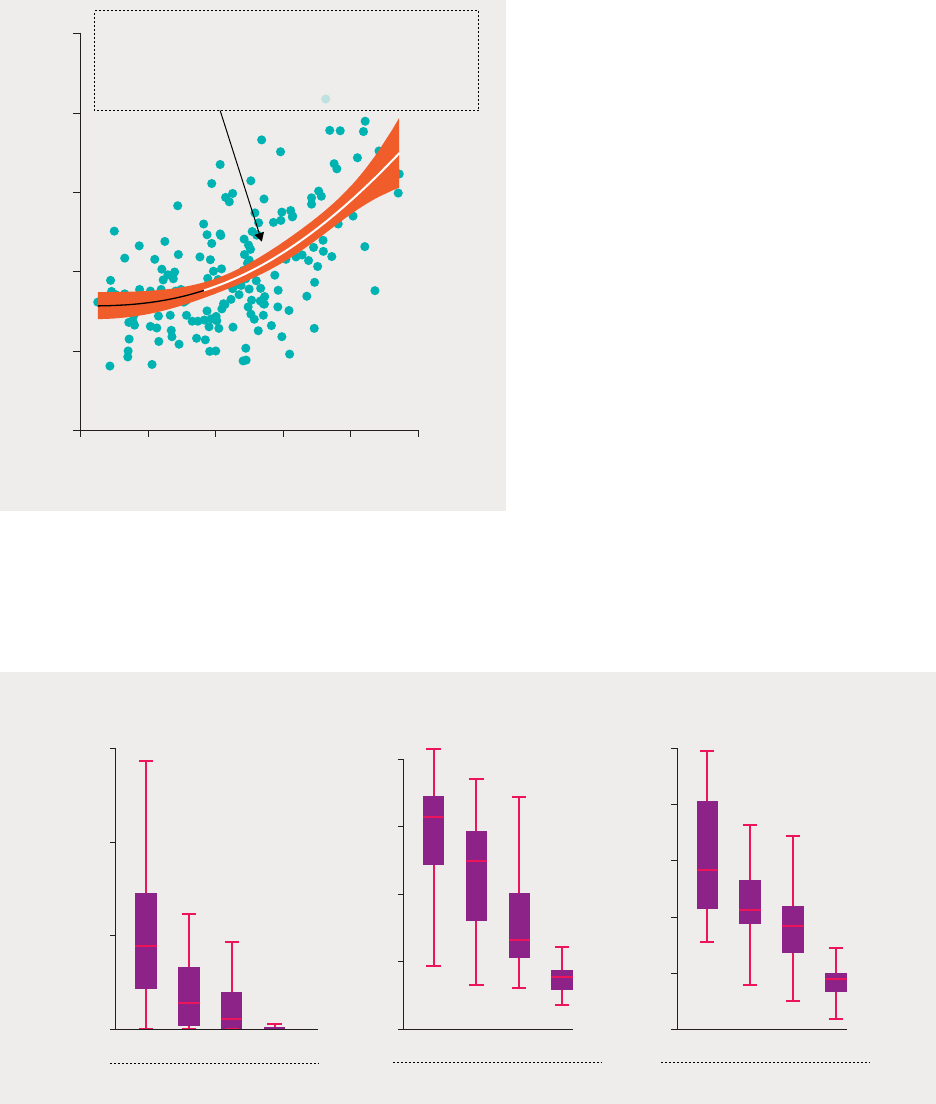

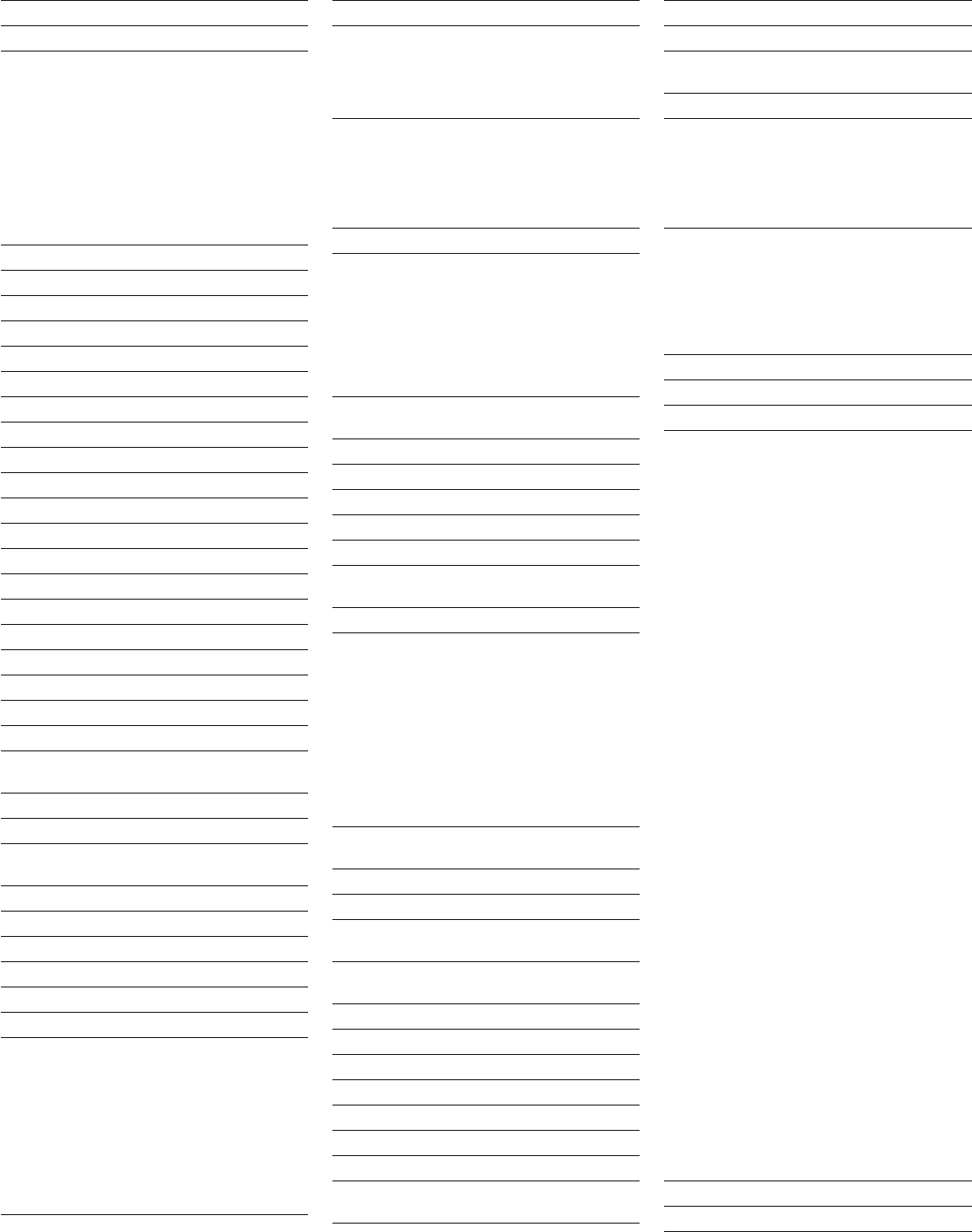

Figure 1 Perceptions of human insecurity are widespread worldwide

Source:

People feeling secure

People feeling moderately or

very insecure

Low and medium

HDI countries

High

HDI countries

Very high

HDI countries

Out of 100 people

More than 6 in 7 people worldwide perceived feeling moderately or very insecure

just before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic.

4 NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

The Covid-19 pandemic makes these interconnec-

tions more apparent and unmasks new accumulat-

ing threats to human security. The uneven pain and

devastation have been widely documented. Women

face the brunt of adaptations to remote work and the

dramatic increase in violence against them. Informal

workers are left outside social protection systems.

People living in urban poverty are hit particularly

hard by the health and economic consequences of the

pandemic. Yet Covid-19 is only one manifestation of

the new Anthropocene context. The Report includes

novel work and estimates of the scale of the threats in

the Anthropocene context.

• Hunger is on the rise, reaching around 800 million

people in 2020, and about 2.4 billion people now

suer food insecurity, the result of cumulative so-

cioeconomic and environmental eects that had

been building before 2019 but were boosted by the

pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

• Climate change will continue to aect people’s vital

core. Even in a scenario with moderate mitigation,

around 40 million people worldwide could die,

mostly in developing countries, as a result of higher

temperatures from now to the end of the century.

• The number of forcibly displaced people has dou-

bled in the past decade, reaching a record high of

82.4 million in 2020.

And forced displacement may

be further accelerated as long as climate change

remains unmitigated.

• Digital technologies can help meet many of the

Anthropocene challenges, but the rapid pace of

digital expansion comes with new threats that

may exacerbate ongoing problems related to, for

example, inequalities and violent conict. Not only

did the ongoing pandemic accelerate a digital shift

in the productive economy, but cybercrime also

skyrocketed, with annual costs projected to reach

$6 trillion by the end of 2021.

• The number of people aected by conict is reach-

ing record highs: today approximately 1.2 billion

people live in conict-aected areas, 560 million of

them outside fragile settings, reecting the spread

of dierent forms violent conict.

• Inequalities are an assault to human dignity.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex

people and members of other sexual minorities

face particular risks of harm to their person in soci-

eties where diversity is not tolerated.

In 87 percent

of 193 countries,

they lack the right of recognition

of their identity and full citizenship.

• Violence against women and girls is one of the cru-

ellest forms of women’s disempowerment.

Subtle

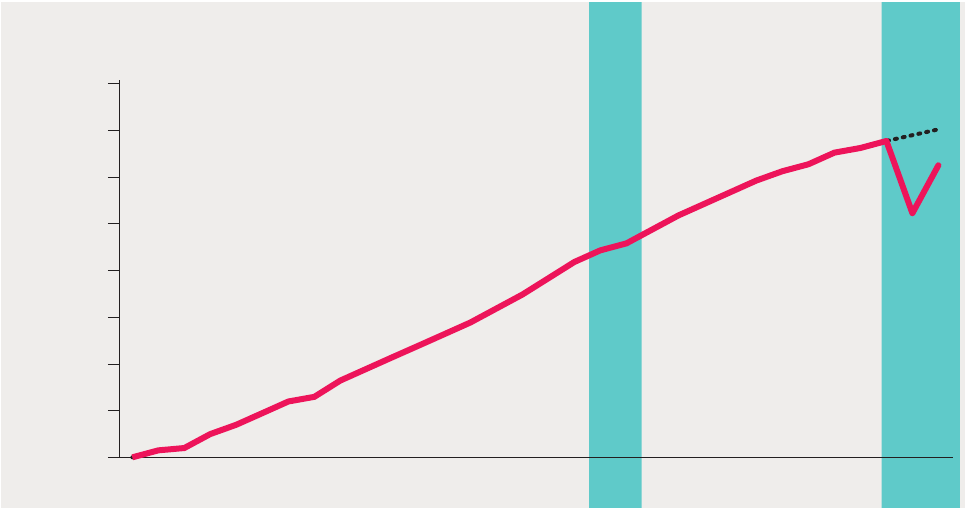

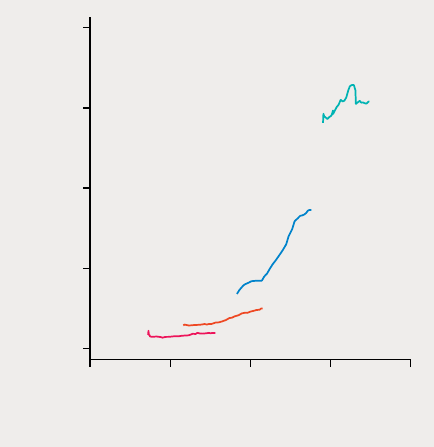

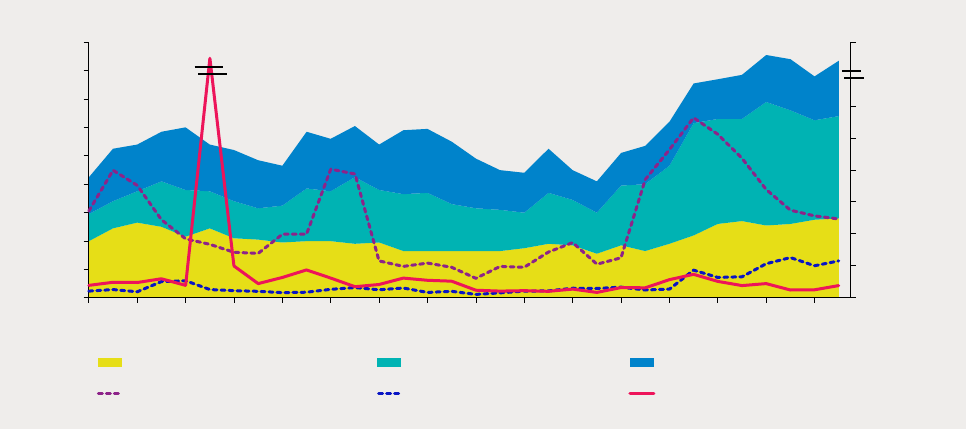

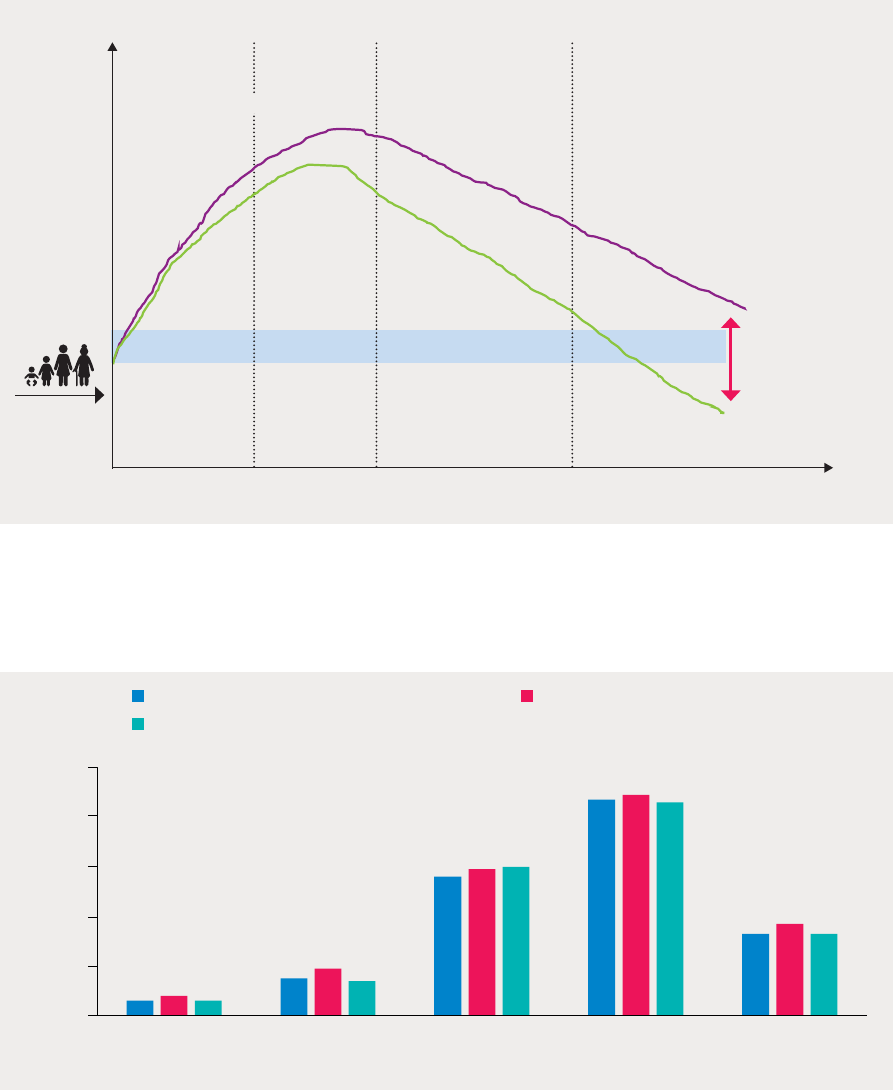

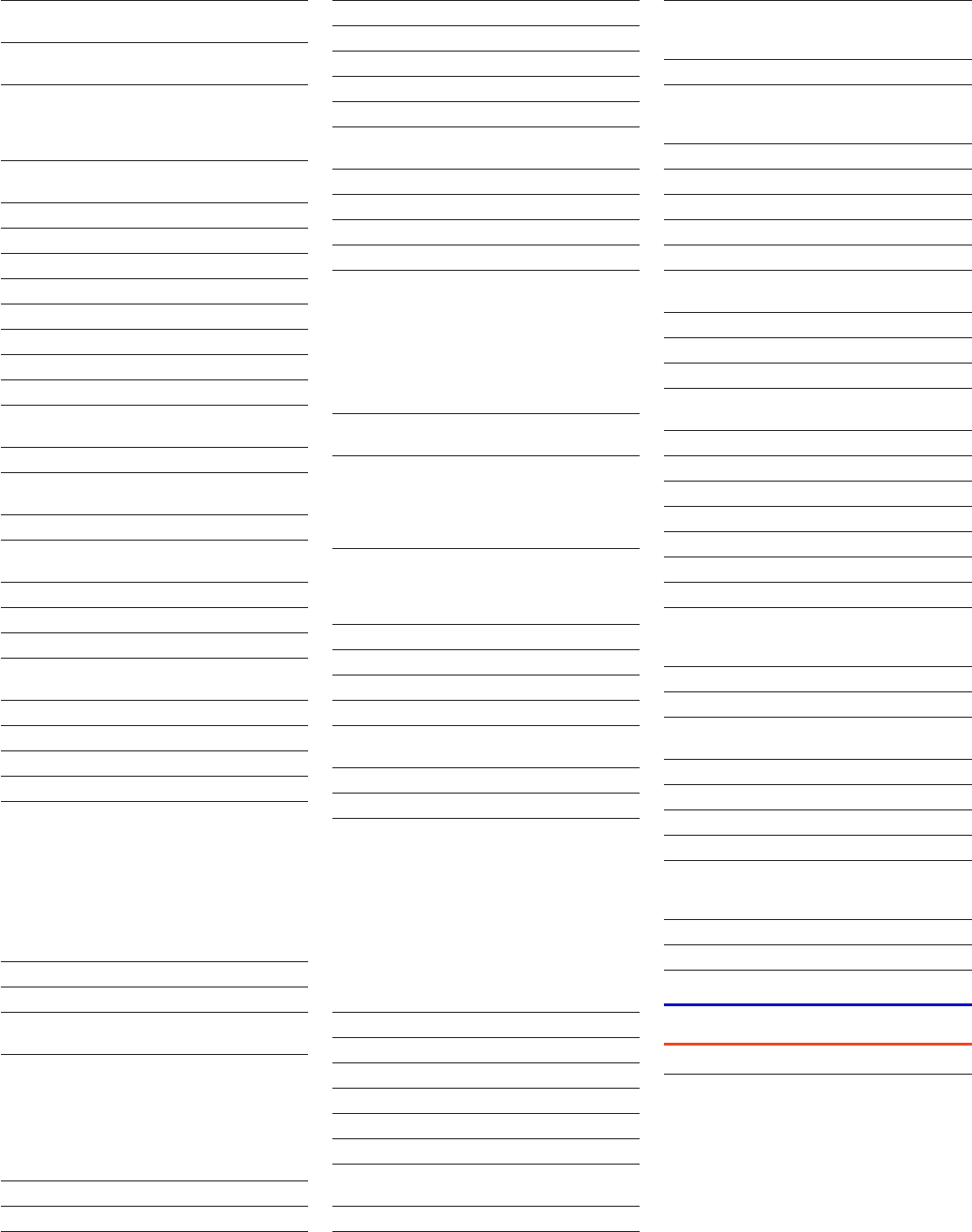

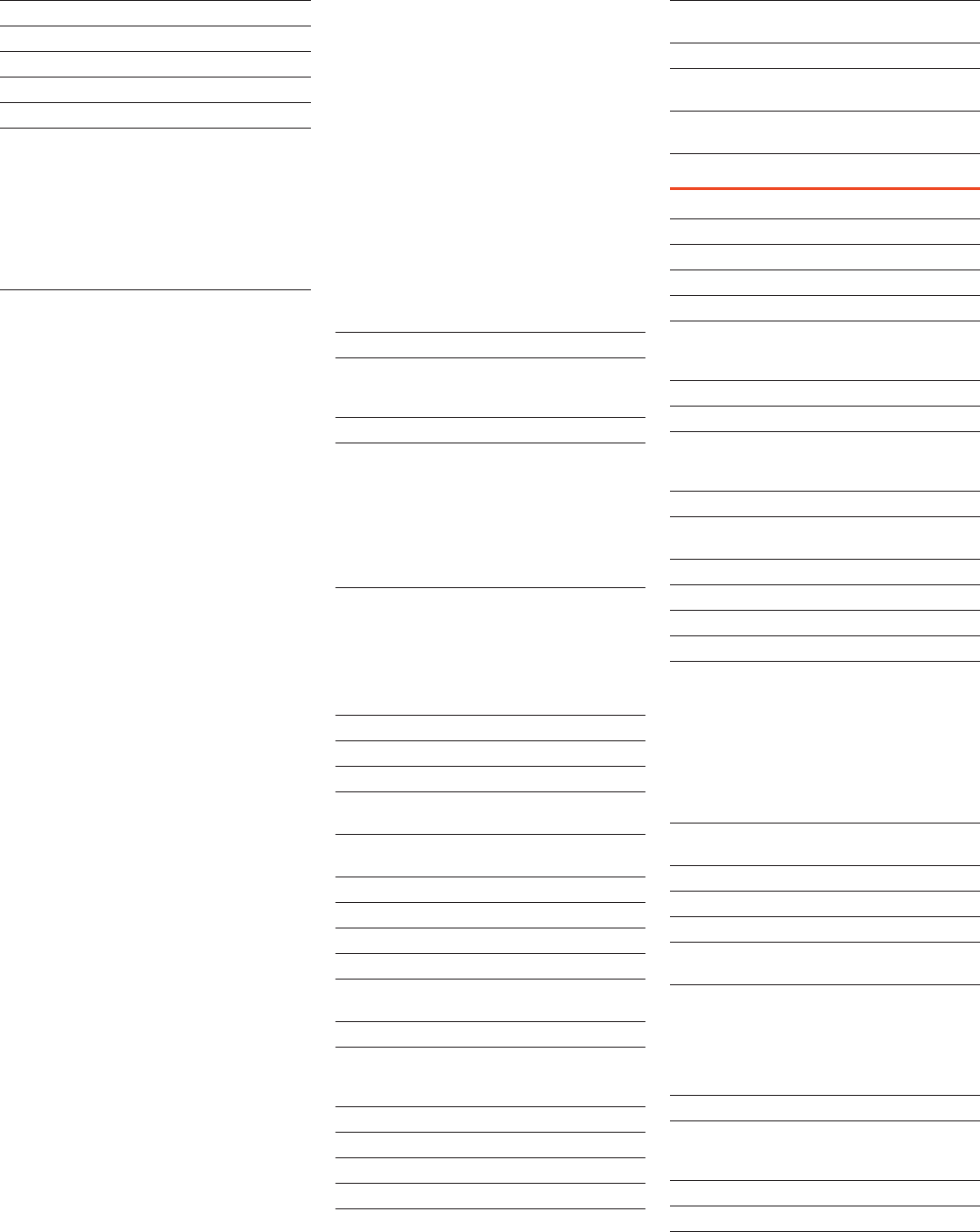

Figure 2 The Covid-19 pandemic has caused an unprecedented decline in Human Development Index values

Source:

0.600

0.620

0.640

0.660

0.680

0.700

0.720

0.740

0.760

The global

financial crisis

Covid-19-adjusted

Human Development Index value

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

1990

Covid-19

OVERVIEW 5

forms of violence and so called microaggressions

build up to such severe forms of violence as rape

and femicide.

In 2020, 47,000 women and girls

were intentionally killed by their intimate partner

or their family. On average, a woman or girl is killed

every 11 minutes by an intimate partner or family

member.

• The gap is large and growing between very high

and low HDI countries in the universalism of

healthcare systems. Countries with weaker, less

universal healthcare systems also face the great-

est challenges in health: the increasing burden

of noncommunicable diseases and the eects of

pandemics.

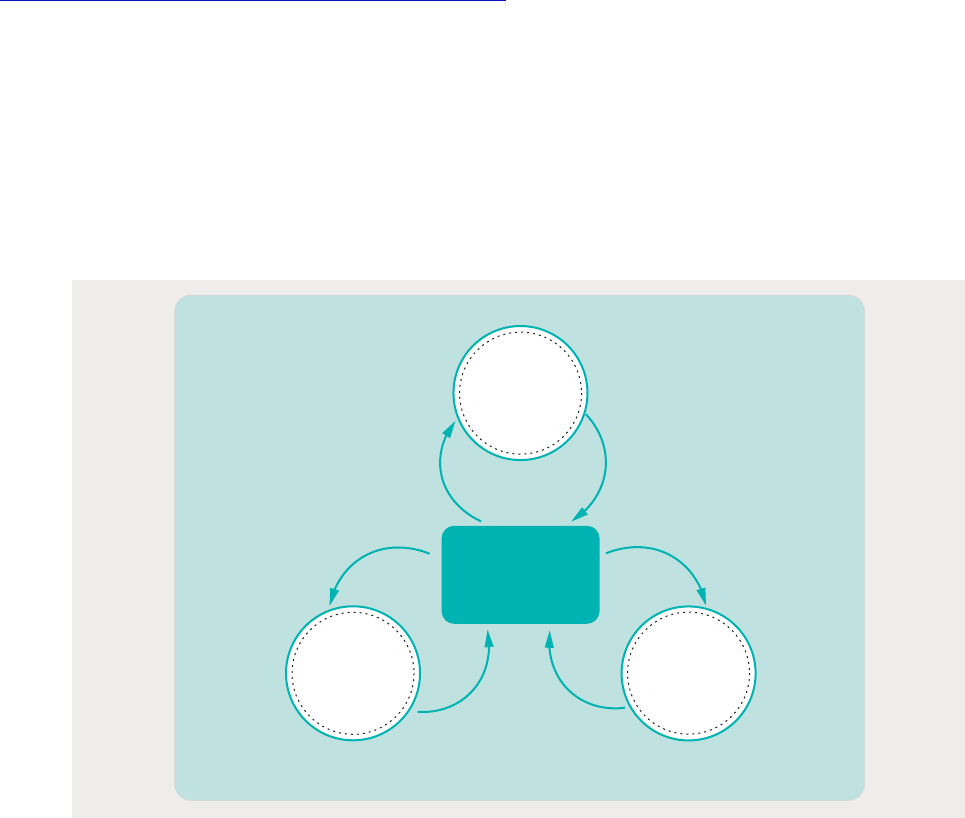

The Report argues for expanding the human secu-

rity frame in the face of the new generation of inter-

connected threats playing out in the context of the

Anthropocene. It proposes adding solidarity to the

human security strategies of protection and empow-

erment proposed by the 2003 Ogata-Sen report.

Solidarity recognizes that human security in the

Anthropocene must go beyond securing individu-

als and their communities for institutions and poli-

cies to systematically consider the interdependence

across all people and between people and the planet.

For each of us to live free from want, from fear and

anxiety and from indignity, all three strategies must

be deployed — for it is protection, empowerment and

solidarity working together that advances human

security in the Anthropocene. Agency (the ability to

hold values and make commitments, regardless of

whether they advance one’s wellbeing, and to act ac-

cordingly in making one’s own choices or in partici-

pating in collective decisionmaking) lies at the core

of this framework (gure 4). Emphasizing agency is a

reminder that wellbeing achievements alone are not

all we should consider when evaluating policies or as-

sessing progress. Agency will also help avoid the pit-

falls of partial solutions, such as delivering protection

with no attention to disempowerment or committing

to solidarity while leaving some lacking protection.

This proposal for enriching the human securi-

ty frame is made in a very particular context, where

perceptions of human insecurity are associated with

low impersonal trust, independent of one’s nancial

situation.

People facing higher perceived human

insecurity are three times less likely to nd others

trustworthy,

a trend particularly strong in very high

HDI countries. Trust is multifaceted and essential for

everyday life, but given this association, trust — across

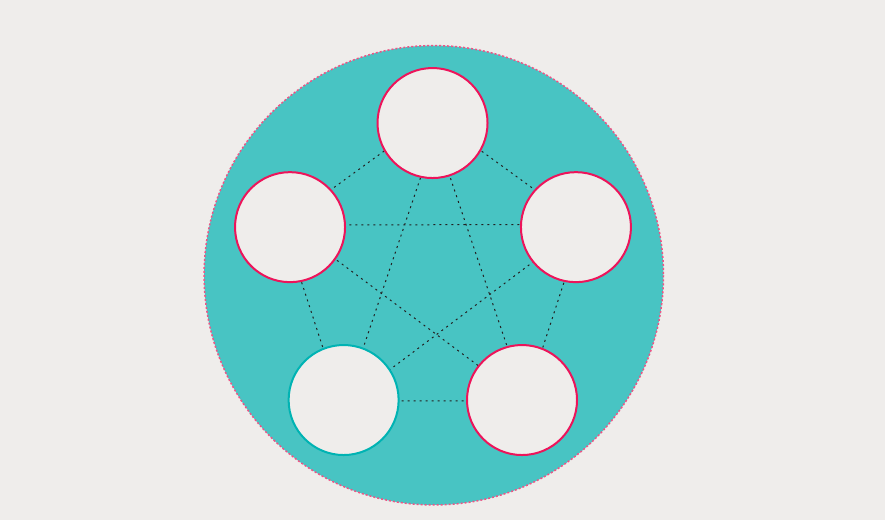

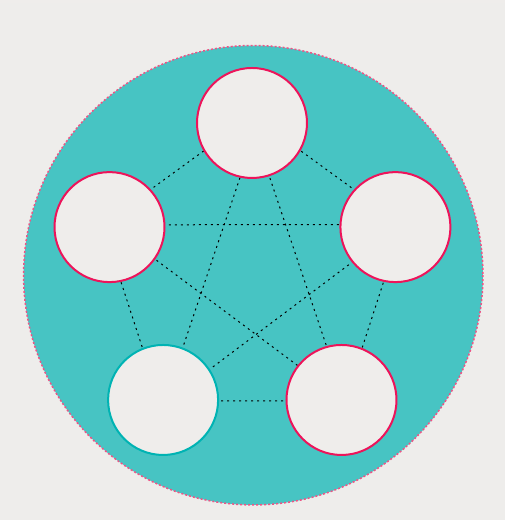

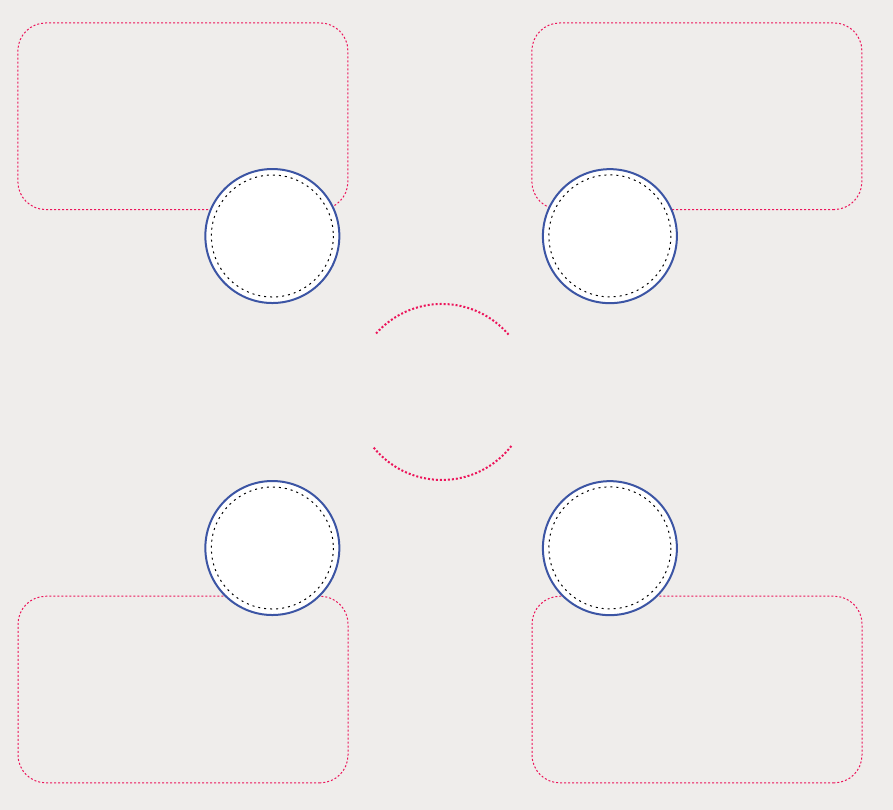

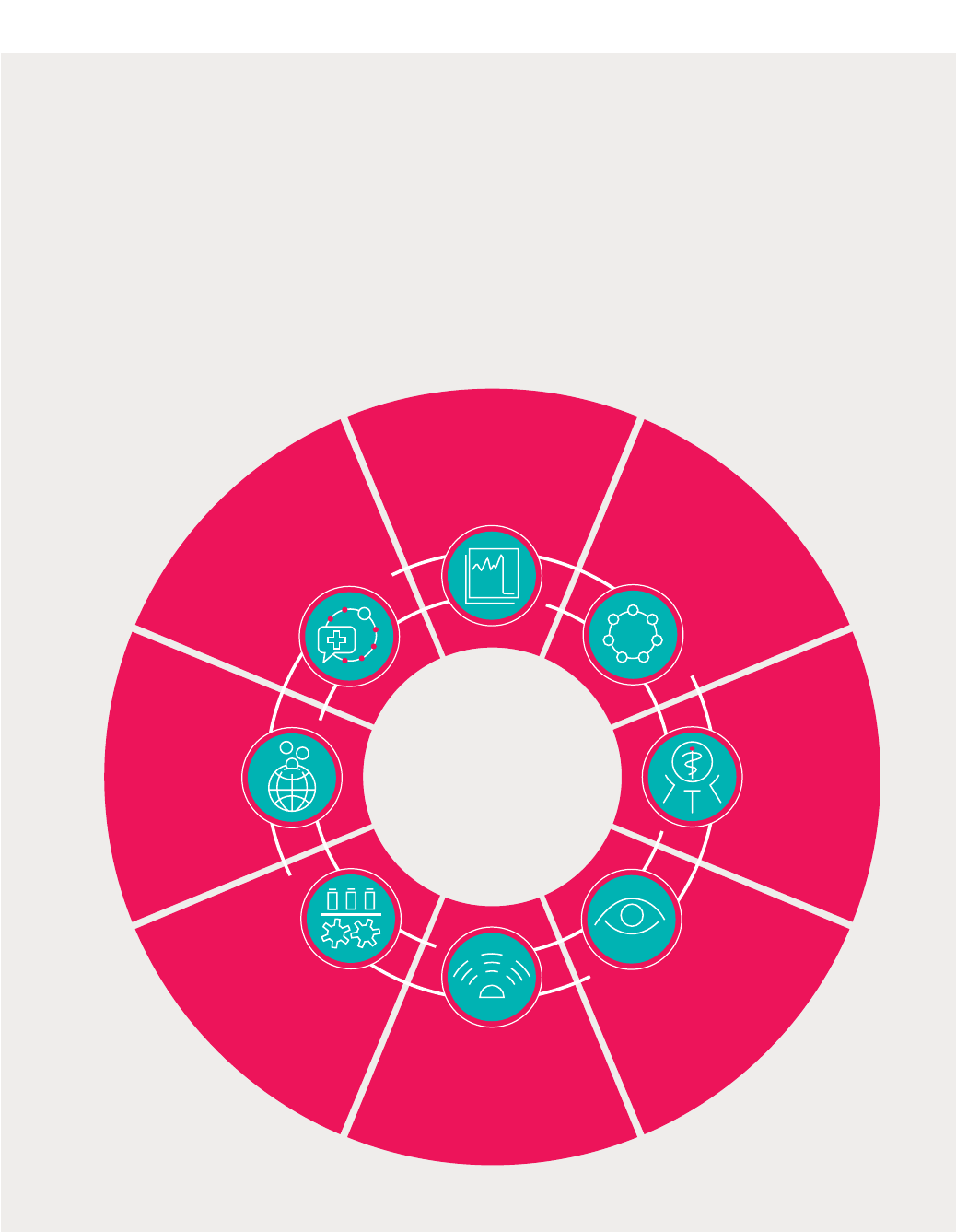

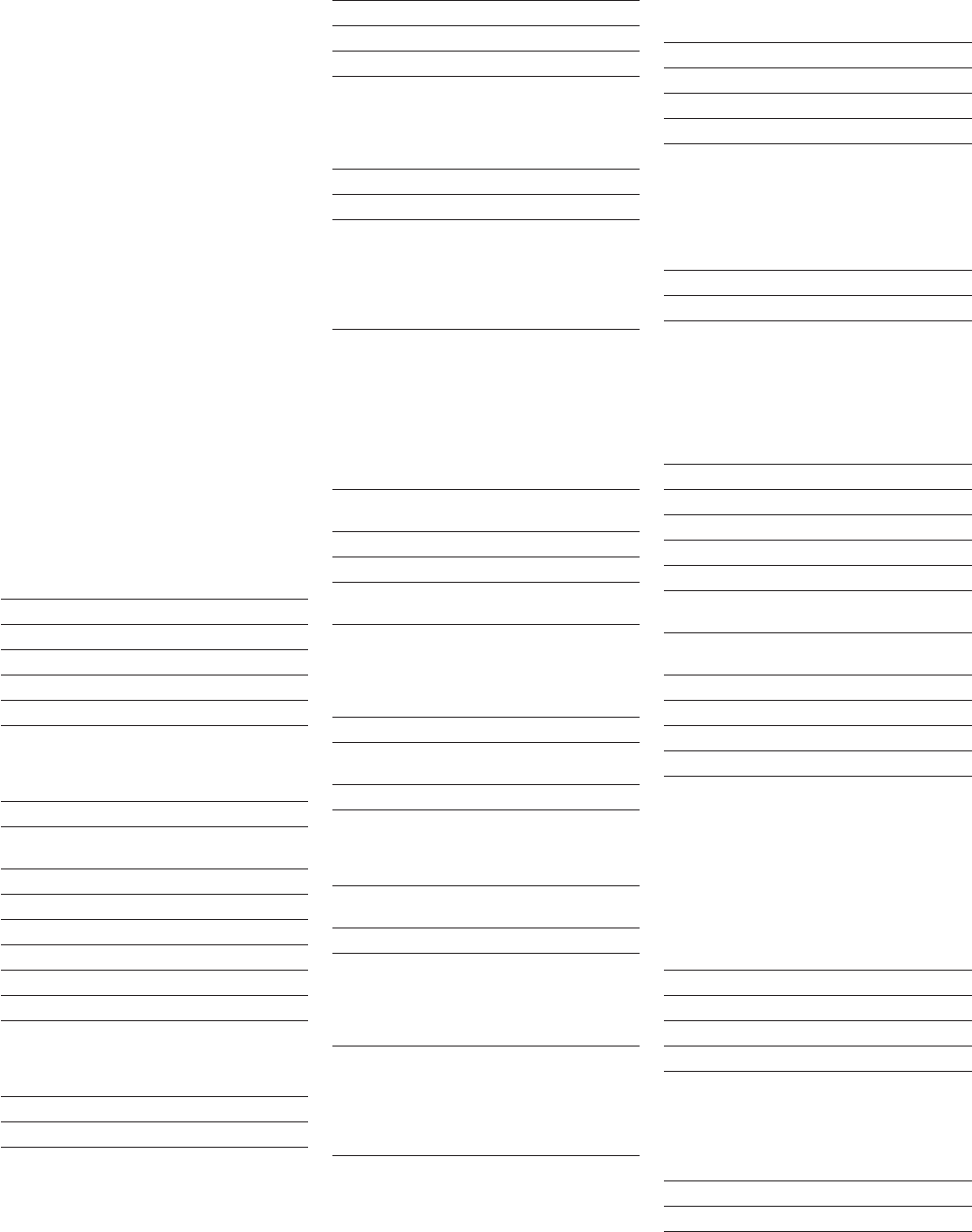

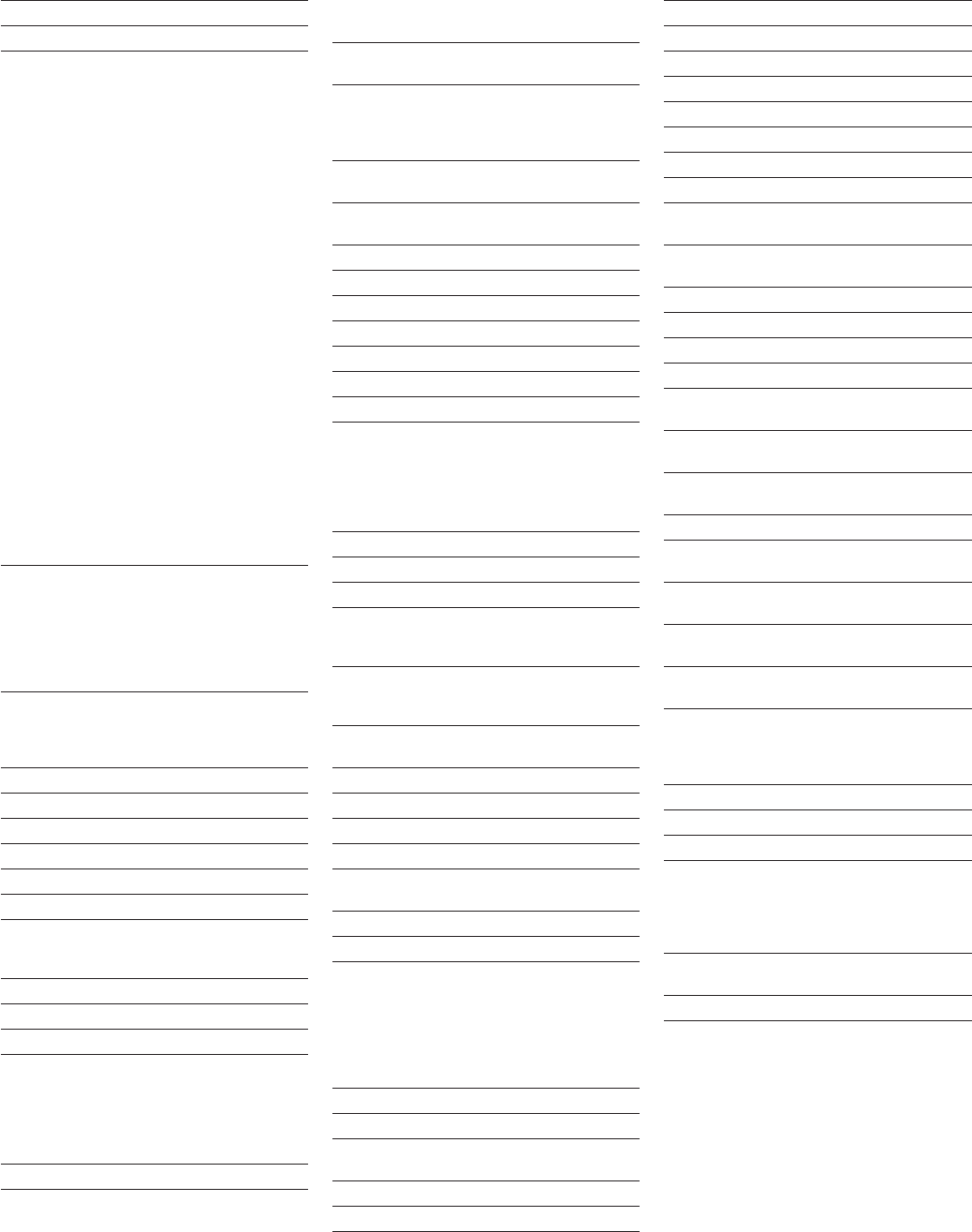

Figure 3 The new generation of human security threats

Source: Human Development Report Office.

Digital

technology

threats

Health

threats

Inequalities

Violent

conflict

Other

threats

A

n

t

h

r

o

p

o

c

e

n

e

c

o

n

t

e

x

t

6 NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

people, between people and institutions, across

countries — may enable or hamper the implementa-

tion of protection, empowerment and solidarity strat-

egies to enhance human security.

The Anthropocene context, with interlinked

human security threats, calls for a bold agenda to

match the magnitude of the challenges, put forward

with humility in the face of the unknown. The alter-

native is accepting fragmented security approaches,

with responses likely de-equalizing, likely reactive,

likely late and likely ineective in the long term. Per-

manent and universal attention to an enriched frame

of human security can end the pathways of human

development with human insecurity that created the

conditions for the Covid-19 pandemic, the chang-

ing climate and the broader predicaments of the

Anthropocene.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

and the Sustainable Development Goals provide an

ambitious set of multidimensional objectives that

inform action at all levels (from the local to the na-

tional) and mobilize the international communi-

ty. But eorts remain largely compartmentalized,

dealing separately with climate change, biodiversity

loss, conicts, migration, refugees, pandemics and

data protection. Those eorts should be strength-

ened, but tackling them in silos appears insucient

in the Anthropocene context. It is imperative to go

beyond fragmented eorts, to rearm the principles

of the founding documents of the United Nations,

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the

UN Charter, which are also the central ideas un-

derpinning the concept of human security. Echoing

the UN Secretary-General’s Our Common Agenda,

doing so in the Anthropocene implies a systematic,

permanent and universal attention to solidarity —

not as optional charity or something that subsumes

the individual to the interests of a collective, but as

a call to pursue human security through “the eyes of

humankind.”

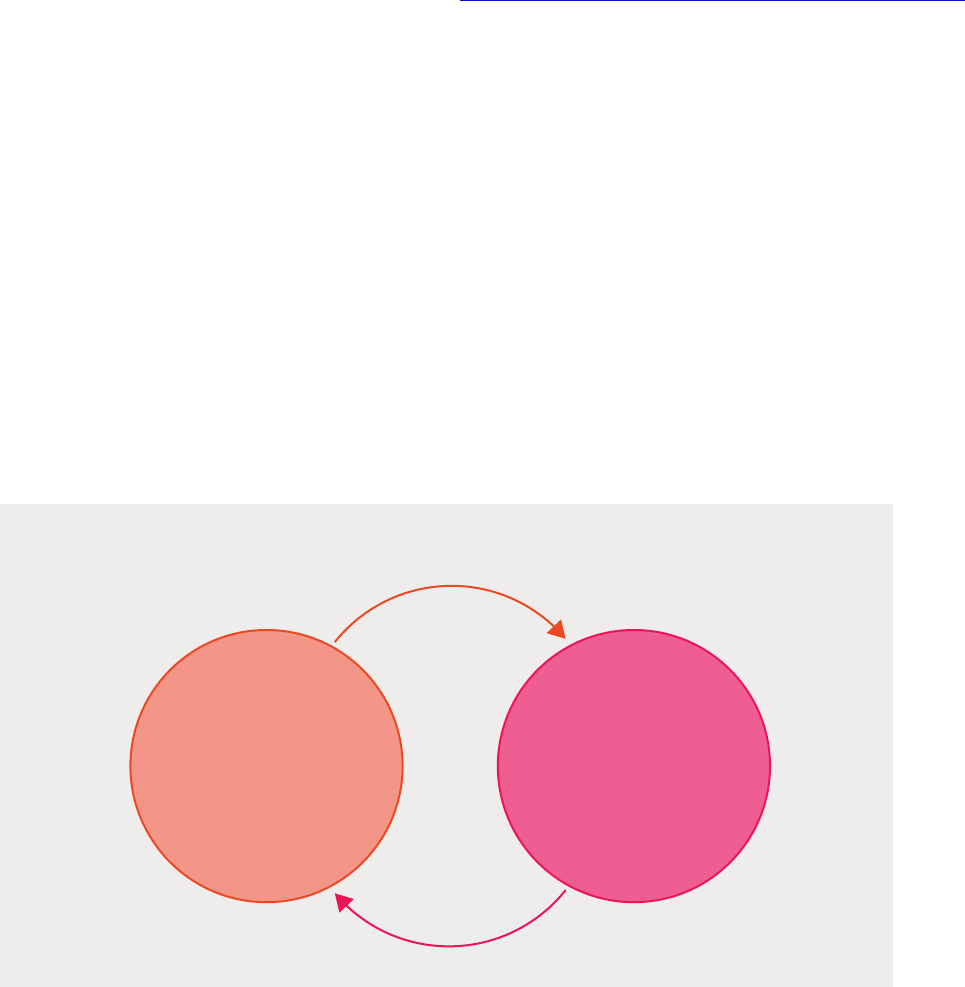

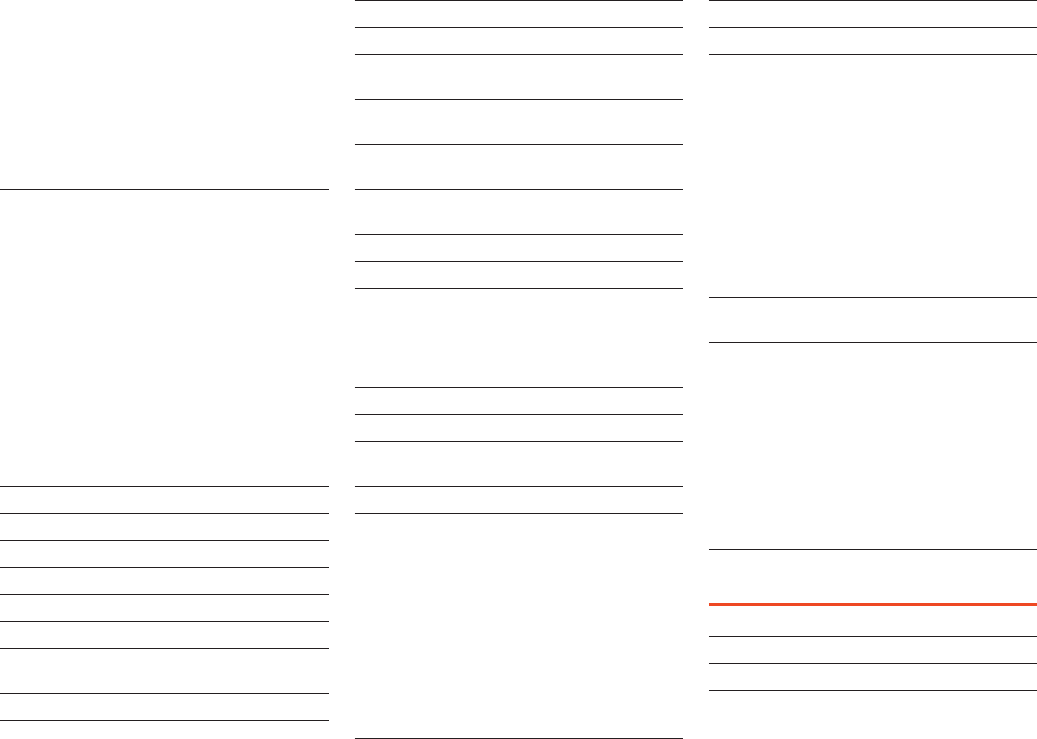

Figure 4 Enriching human security for the Anthropocene

Source: Human Development Report Office.

Protection

Empowerment

Solidarity

Agency

Enables

Promotes Promotes

Enables

Trust

Enables Promotes

OVERVIEW 7

Expanding

human security

through greater

solidarity in the

Anthropocene

PART

I

Human security:

Apermanent and

universal imperative

CHAPTER

1

12 NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

CHAPTER 1

Human security: A permanent and universal

imperative

Just before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, as the world

reached unprecedented development levels, six of

every seven people around the world felt insecure.

Indeed, as many development indicators were mov-

ing up, people’s sense of security was coming down.

The pandemic put a stop to progress in human devel-

opment, deepening the continuing onslaught on peo-

ple’s perceptions of security (box 1.1).

It is not hard to understand how Covid-19 has led

people to feel more insecure.

But what accounts for

Box 1.1 The Covid-19 pandemic as a deep human security crisis continues into 2022

The Covid-19 pandemic has affected nearly everyone

and turned into a full-fledged human security and

human development crisis. The most tragic impact

has been a worldwide death toll of more than 10 mil-

lion (the excess mortality in 2020–2021).

1

But impacts

go well beyond this distressing record. Most countries

have suffered acute recessions. School closures and

restrictions on people’s movement have disrupted

the education of millions of children worldwide, with

the resulting costs to learning still to be assessed.

Many countries turned to remote learning, but an

estimated two-thirds of the world’s school-age chil-

dren lack internet access in their homes.

2

There have

been serious setbacks in women’s empowerment

and gender equality and increasing violence against

women.

3

Women have also been disproportionately

affected by job losses.

4

It is possible to track part of the pandemic’s effects

on human development through the Covid-19-adjusted

Human Development Index. The index retains the

standard Human Development Index (HDI) dimen-

sions but modifies the expected years of schooling

indicator to reflect the effects of school closures and

the availability of online learning on effective at-

tendance rates. In 2020 there was a sharp reduction

across all the three dimensions of the HDI: health,

knowledge and living standards.

The crisis continued in 2021, with human develop-

ment levels (as measured by the Covid-19-adjusted

HDI) remaining well below pre-Covid-19 levels. Even

with the availability of — very unequally distributed

— Covid-19 vaccines, the economic recovery that

started in many countries and the partial adaptation

of education systems, the crisis deepened in health,

with a continued decline in life expectancy at birth. In

2021 the global Covid-19-adjusted HDI value had yet

to recover the equivalent of approximately 5 years of

progress, according to new simulations (see figure).

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused an unprecedented decline in Human Development Index values

Source:

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, the International Monetary Fund, International Telecommunication Union, the Human Mortality Data-

base, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Notes

1.IHME 2021. 2.UNICEF and ITU 2020. 2.UN Women 2021b; Vaeza 2020. 3.ILO 2021a.

0.600

0.620

0.640

0.660

0.680

0.700

0.720

0.740

0.760

The global

financial crisis

Covid-19-adjusted Human

Development Index value

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

1990

Covid-19

13

the startling bifurcation between the improvements

in people’s wellbeing and the declines in their per-

ception of security that was unfolding before the pan-

demic? That is the question that animates this Report.

To address it, the Report takes the premise that

the concept of human security provides a unique per-

spective that is both insightful and fruitful in suggest-

ing how to advance human development with less

insecurity. And in so doing, building on decades of

analytical and policy work, the Report also aims to

enrich the frame of human security.

“

The Report takes the premise that the

concept of human security provides a

unique perspective that is both insightful

and fruitful in suggesting how to advance

human development with less insecurity

There may be many reasons for people to feel inse-

cure, and they will vary according to social and indi-

vidual contexts. They are manifestations of objective

threats. Some social imbalances

have been build-

ing for decades, as the 2019 Human Development

Report highlighted.

But awareness is now growing

about dangerous planetary changes that compound

other well-identied drivers of human insecurity. For

example, social tensions and their implications for

conict interact both with climate hazards (droughts,

wildres, storms) and with what the energy transition

means for jobs and opportunities. Or indeed, how a

global pandemic that followed more frequent out-

breaks of new or emerging zoonotic diseases is linked

to pressures on biodiversity.

As pandemic response

veteran Richard Hatchett notes, “Except we’re now

in a dierent world. This is denitely not a once-in-

a-century problem. Covid-19 is the seventh global

infectious-disease crisis of the 21st century: SARS,

avian inuenza, swine u, MERS, Ebola and Zika

preceded it. It looks like roughly every three years

you’re going to have a global infectious-disease crisis,

and that tempo is probably increasing.”

As the 2020 Human Development Report ex-

plored,

dangerous planetary changes result from

human pressures on planetary processes — from the

climate system to material cycles disrupted by the use

and introduction of materials at an unprecedented

scale and speed and to the threats to the integrity of

ecosystems from tropical forests to coral reefs and to

entire oceans. Those changes are so unprecedented

in human history and in the 4.6 billion year geological

timeline of the planet that they have been described

as a new geological epoch or event: the Anthropo-

cene, the age of humans. There are glaring inequali-

ties in contributions to planetary pressures — now and

historically — and in power between those overextract-

ing and those bearing the consequences. This hap-

pens across countries but, crucially, within countries

as well, with some groups systemically more aect-

ed than others. Human rights violations overlap with

the destruction of ecosystems, as with the forced and

slave labour in the very shing eets that are destroy-

ing ocean ecosystems. Biodiversity losses often par-

allel not only the destruction of livelihoods but also

cultural losses, such as the disappearance of languag-

es, aecting many indigenous peoples and local com-

munities. Collective decisions, national and global,

that could ease planetary pressures are more dicult

to reach and implement, thus slowing, or even pre-

venting, action to ease planetary pressures.

With this the dichotomy of “human development

with human insecurity” may appear far less puzzling

— because the patterns of development that we have

been pursuing inict many of the drivers of insecu-

rity we are confronting. This chapter explores how

the human security concept is a useful lens through

which to understand this new context, elaborated

further in chapter 2, and how the human security

frame can be enriched to provide new perspectives

on specic threats to human security that play out in

this new context and are interconnected, global and

mostly human-made — threats explored in part II of

the Report.

This chapter has two main ndings. First, the

human security frame points to the limitations of

evaluating policies and measuring progress by look-

ing at wellbeing achievements alone. The chapter

identies the neglect of agency as a major blind spot

and suggests making agency a central focus of atten-

tion for decisionmakers. Second, the human securi-

ty frame itself can be enriched by addressing a blind

spot of its own: the neglect of the new Anthropocene

reality and what that implies. The chapter rearms

the relevance of the individually centred approaches

of protection and empowerment to advance human

security. It suggests adding an approach based on

solidarity — beyond borders and across peoples,

14 NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

cognizant of our interdependencies in a globalized

world and our common fate on a planet undergoing

dangerous changes as a result of our actions.

Becoming richer amid a vast

sea of human insecurity

An age of widespread — and growing —

perceptions of human insecurity

Human security is about living free from want, free

from fear and free from indignity. It is about protect-

ing what we humans care most about in our lives. In

2012 the UN General Assembly reected a consensus

that human security would be considered, “The right

of people to live in freedom and dignity, free from

poverty and despair. All individuals, in particular

vulnerable people, are entitled to freedom from fear

and freedom from want, with an equal opportunity

to enjoy all their rights and fully develop their human

potential.”

Annex 1.1 provides a brief account about

the origins and progression of the human security

concept, which continues to evolve.

“

Human security is about living free

from want, free from fear and free from

indignity. It is about protecting what we

humans care most about in our lives

When the human security concept was introduced

in the 1994 Human Development Report,

it was

rapidly recognized as a radical departure from the

predominant view of security at the time, because it

shifted the focus towards the real subjects — people —

and away from territorial security. That seminal work

also emphasized three additional characteristics of

human security — universal, multidimensional and

systemic — which have heightened relevance today

as issues aecting people’s security become part of a

new set of interlinked threats on a planet undergoing

dangerous changes because of human pressures.

Using a human security lens implies considering

people’s views.

What constitutes fear, want and dig-

nity depends largely on people’s beliefs, which are

formulated based on a combination of very specic

and objective factors, along with elements that may

be more subjective. But this is not a problem because

attention to subjectivities — considering how people

themselves view and understand their situation, vul-

nerabilities and limits — is core to the analytical fram-

ing of human security.

As argued in more detail later

in the chapter, beliefs are important elements inu-

encing people’s choices, values and commitments.

In fact, Kaushik Basu, in exploring the relationship

between law and economics, has argued for the cen-

tral role of beliefs in shaping even attitudes towards

the law:

“The might of the law, even though it may be

backed by handcus, jails, and guns, is, in its ele-

mental form, rooted in beliefs carried in the heads

of people in society — from ordinary civilians to the

police, politicians and judges, intertwining with

and weaving into one another, reinforcing some

and whittling down others, creating enormous ed-

ices of force and power, at times so strong that

they seem to transcend all individuals, and create

the illusion of some mysterious diktat enforced

from above. In truth, the most important ingredi-

ents of a republic, including its power and might,

reside in nothing more than the beliefs and expec-

tations of ordinary people going about their daily

lives and quotidian chores.”

So, it is useful to explore how living free from

want, living free from fear and living free from indig-

nity relate to beliefs and interact with one another,

starting by considering dignity, which is most direct-

ly a belief.

• Dignity. Dignity is grounded on the universal belief

that everyone has equal inherent worth and value,

enshrined in Article 1 of the Universal Declaration

of Human Rights: “All human beings are born free

and equal in dignity and rights.”

Its importance

was reiterated as a central aspiration of the 2030

Agenda for Sustainable Development: “to ensure

that all human beings can full their potential in

dignity.”

Threats to one’s dignity emanate not only

from objective deprivations (such as not having

basic needs met, linking to the aspiration of being

free from want) but also from stigma. Sometimes,

the very interventions that seek to address material

deprivations may hurt people’s dignity by stigma-

tizing them and inducing emotions of shame,

especially when poverty is attributed to negative

individual dispositions.

Dignity goes beyond

15

avoiding being physically harmed or shamed to

having autonomy

and agency — a central idea

that is the core of arguments developed later in the

chapter. Implications of this understanding of dig-

nity include that interventions aimed at addressing

freedom from want with dignity imply the need to

both mitigate stigma and promote empowerment

and that interventions need to be culturally sensi-

tive and responsive.

• Fear. Beliefs are also important in triggering emo-

tions (even if not the only determinant; percep-

tual elements also matter). The emotion of fear

involves beliefs about bad things that may happen

in the future (if something bad is certain to happen,

it is likely to trigger an emotion of despair),

often

associated with perceiving “low certainty and low

sense of control.”

Thus, the emotion of fear, a

powerful driver of behaviour,

is inuenced by a

host of factors, from individual cognitive processes

to external and contextual conditions. People form

beliefs about the possibility that painful and harm-

ful events may unfold in the future, often based on

objective elements that can give them reason to be

fearful.

This includes the possibility of suering

“assaults on their sense of dignity,”

once again

showing the interlinkages across the three aspira-

tions that dene human security.

• Want. Beliefs also come into play when assessing

want, which is determined not only by meeting

basic metabolic needs but also by individual aspi-

rations and relative assessments of what people in

a community are expected to achieve. As Amartya

Sen has often reminded us, Adam Smith’s deni-

tion of not being in poverty was to be able to wear

a linen shirt — not because linen protects someone

from the elements but because it is required to

interact socially in the community, without shame.

Thus, there are interlinkages between freedom

from want and living in dignity. This echoes anthro-

pological perspectives on want. As Mary Douglas

put it, “At the local level, wants are part of a feed-

back cycle between the relations of production and

consumption. Wants and needs are not ordered

according to private preferences. Other people

collectively try to solve problems of coordination,

the solutions impose ordering on ego’s preferences.

The cultural process denes wants, and poverty is

culturally constructed.”

“

In addition to being high, the perception

of human insecurity has increased over time

for most countries with comparable data

The formulation of beliefs is thus clearly the result

of a complex constellation of factors. It is not easy,

and it may be impossible, to measure beliefs with

the precision that we can assign to objective indica-

tors such as income or education achievements. But

that does not imply that there are not objective vul-

nerabilities that stimulate particular beliefs and that

this is often the result of well-reasoned processes. As

argued later in the chapter, and more extensively in

chapter 2, there are strong reasons to associate the

new context of the Anthropocene, and the inequali-

ties that characterize it, as the background against

which a new generation of threats to human security

is playing out.

The Index of Perceived Human Insecurity

To get a sense of how people understand and per-

ceive their security beyond what can be grasped from

objective indicators of achievements in wellbeing,

this Report introduces the Index of Perceived Human

Insecurity (I-PHI; see annex 1.2 for details).

It is

based on population- representative data from the

World Values Survey for 74 countries and territories

covering more than 80 percent of the world’s people.

It captures perceived threats across dierent dimen-

sions of daily life in citizen security, socioeconomic

security and violent conict.

The results are striking.

Most people in the world feel insecure: fewer than 1

in 7 people at the global level feel secure or relatively

secure.

More than half of the global population feels

aected by very high human insecurity, as specied

on the I-PHI.

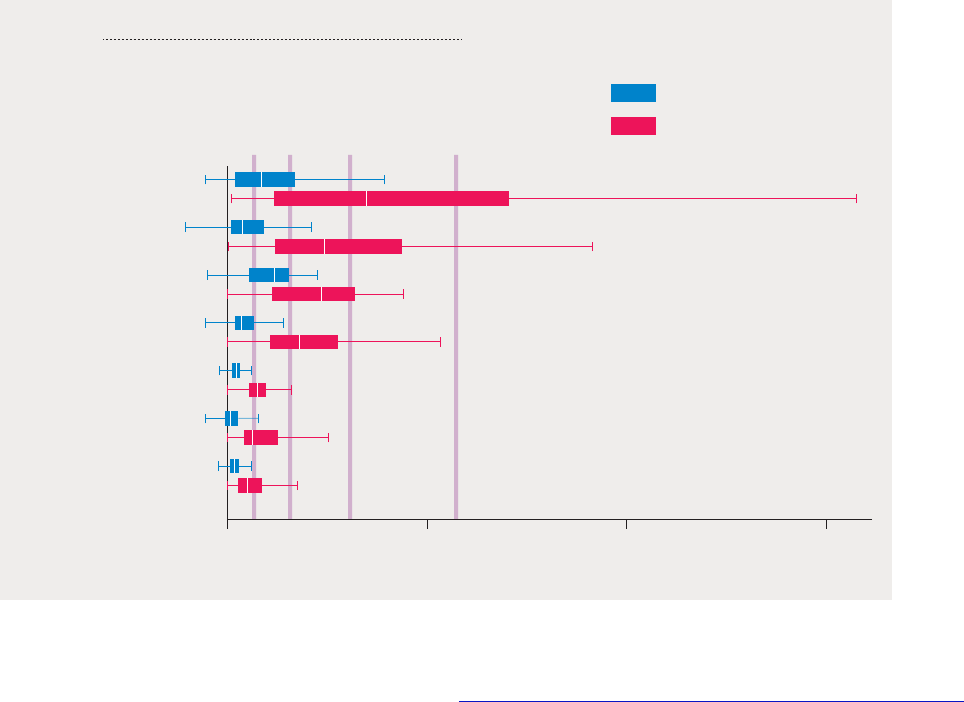

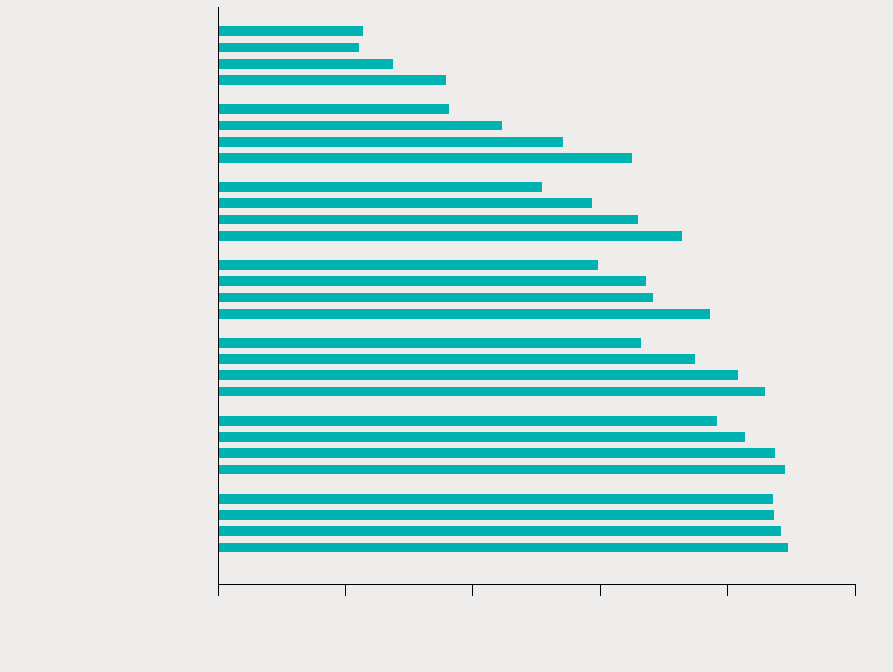

Perceived human insecurity is high across all

Human Development Index (HDI) groups, with more

than three-quarters of the population feeling inse-

cure, even in very high HDI countries (gure 1.1). But

lower HDI countries register even higher perceived

human security, suggesting a negative association be-

tween HDI value and I-PHI value (gure 1.2).

In addition to being high, the perception of human

insecurity has increased over time for most countries

with comparable data. This increase registered across

16 NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

all HDI groups, but some of the largest increases were

in very high HDI countries (gure 1.3).

This suggests that the positive association be-

tween HDI value and I-PHI value gleaned from the

cross-sectional analysis may not reveal much about

the extent to which achievements in wellbeing can

insulate people from feeling insecure. In fact, when

individuals, rather than countries, are grouped by

I-PHI value, the higher the perception of human se-

curity, the higher the level of trust in others tends to

be, a result that holds for dierent levels of satisfac-

tion with the nancial situation (gure 1.4). But the

opposite is not the case: for people who feel very in-

secure, greater nancial satisfaction is not associated

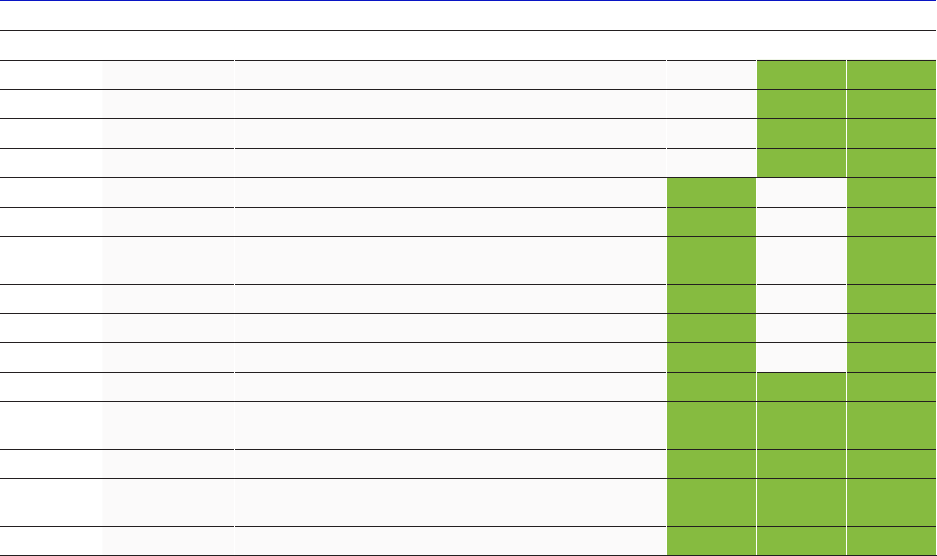

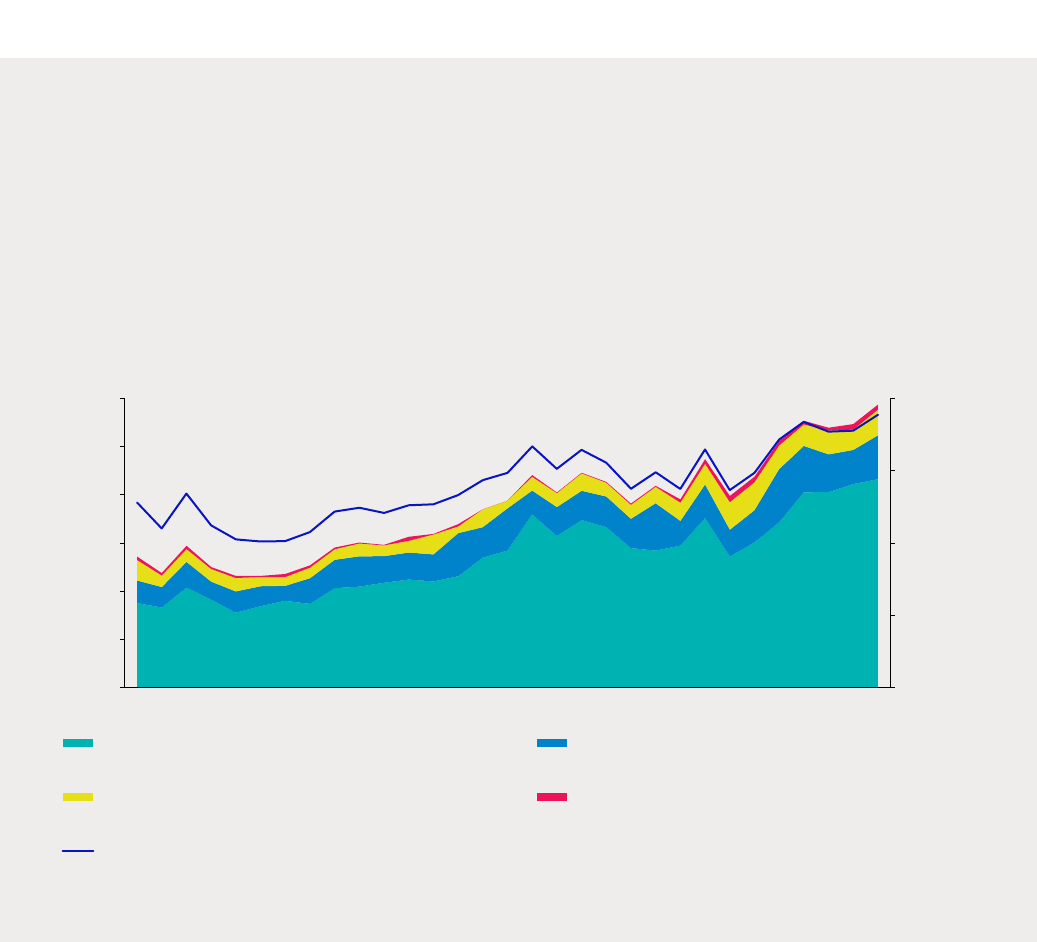

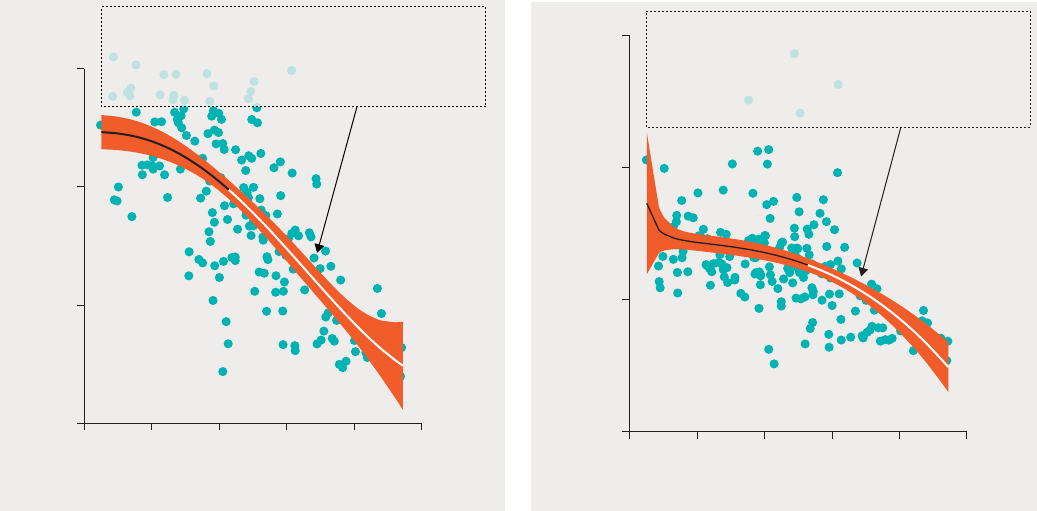

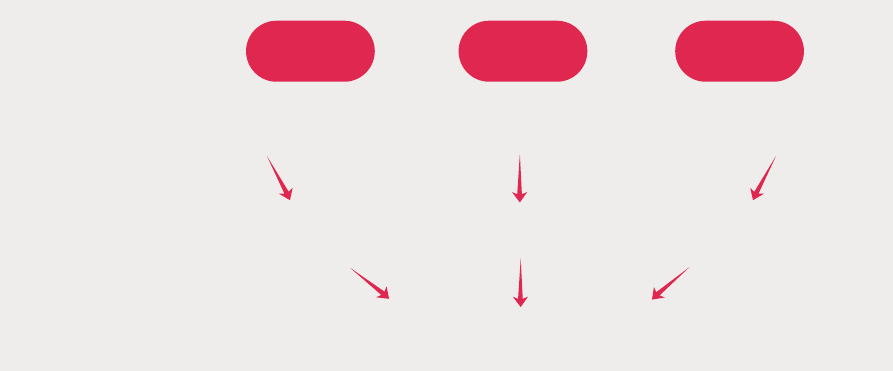

Figure 1.1 Even in very high Human Development Index countries, less than a quarter of people feel secure

Source: Human Development Report Office, based on World Values Survey, latest available wave.

8%

29%

64%

Low and

medium Human

Development

Index

Secure Moderately insecure Very insecure

14%

31%

55%

23%

40%

37%

High

Human

Development

Index

Very high

Human

Development

Index

Perceived insecurity:

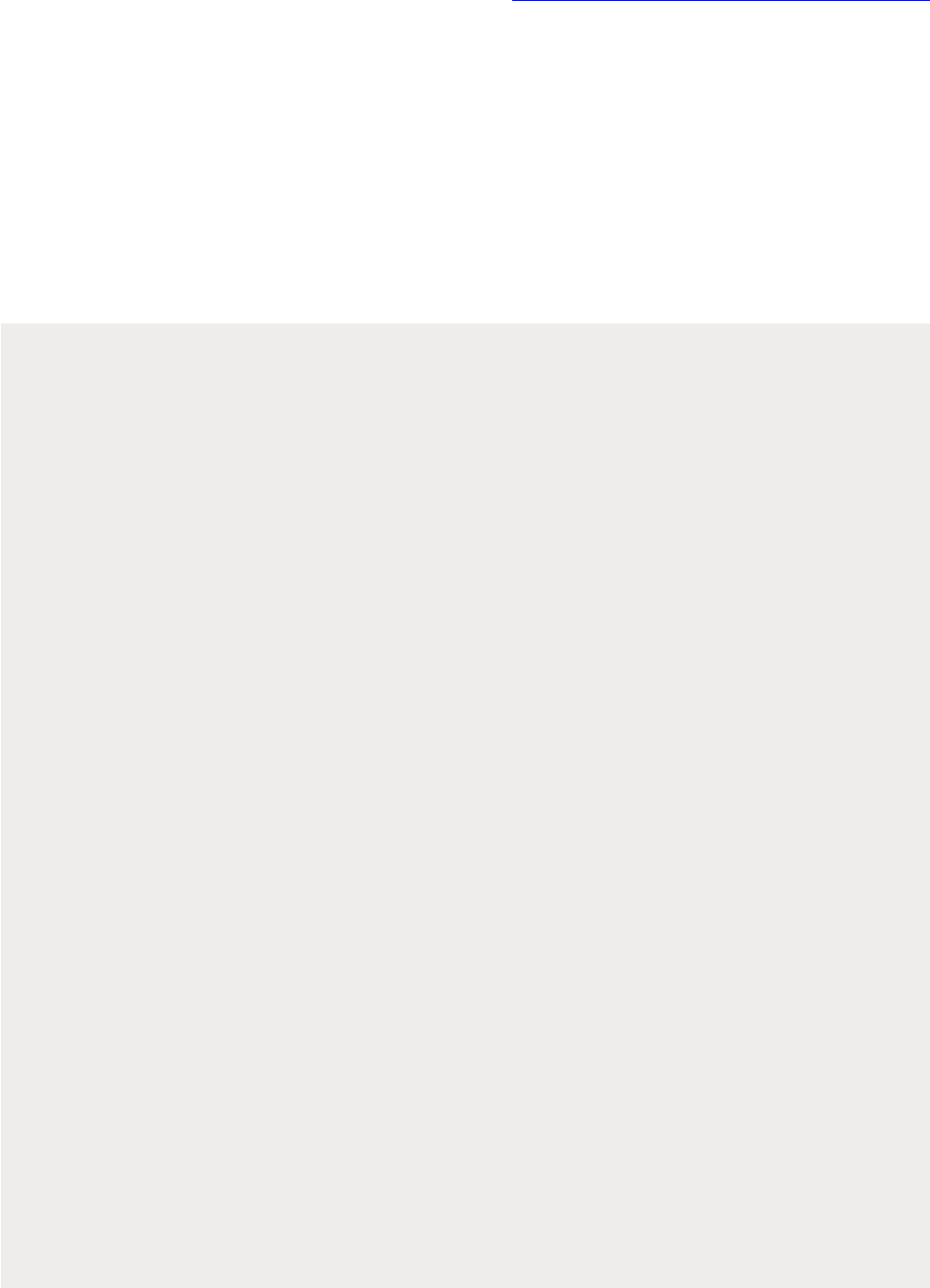

Figure 1.2 Human insecurity tends to be higher in countries with lower Human Development Index values

Source:

0

Index of Perceived Human Insecurity value, most recent year

0.8

0.500 0.600 0.900 1.0000.700 0.800

Human Development Index value, 2019

0.6

0.4

0.2

17

Figure 1.3 Human insecurity is increasing in most countries— and surging in some very high Human

Development Index countries

Note: Bubble size represents the country population.

a. Refers to the change between waves 6 and 7 of the World Values Survey for countries with comparable data.

Source:

Change in Index of Perceived

Human Insecurity value

a

0.500 0.600 0.900 1.0000.700 0.800

Human Development Index (HDI) value, 2019

Increase in

perceived

insecurity

Reduction in

perceived

insecurity

Very high

HDI countries

0.15

0.10

0.05

0

–0.05

–0.10

Figure 1.4 Where human security is higher, trust tends to be higher, regardless of satisfaction with one’s

financial situation

Note: Pooled individual-based data with equal weights across countries.

Source:

0.13

0.19

0.26

0.15

0.24

0.35

0.16

0.25

0.44

0

0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4

Dissatisfied

Moderately

dissatisfied Satisfied

Relatively secure

Perception of insecurity

Moderately insecure

Very insecure

Satisfaction with financial situation

Level of trust

Level of trust Level of trust

18 NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

with a signicant jump in trust. This strong link be-

tween human security and trust also holds when in-

come and life satisfaction are controlled for.

Given

the importance of this nding for the conclusions

later in the chapter, it is crucial to be clear about the

meaning that emanates from answers to the World

Values Survey’s trust question, how it can be inter-

preted and the cautions that must be borne in mind.

What is trust?

Trust is yet another belief.

But what is trust, exact-

ly? It has been dened in multiple ways in dierent

contexts (box 1.2). In the context of the World Val-

ues Survey, it is measured by answering the ques-

tion, “Generally speaking, would you say that most

people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful

Box 1.2 Trust’s many faces

Trust is a complex concept. As sociologist Blaine

Robbins wrote, “Despite decades of interdisciplinary

research on trust, the literature remains fragmented

and balkanized with little consensus regarding

its origins.”

1

Even with this lack of consensus in

the definition and origins, there is widespread

belief that trust has been an important element in

the development and sophistication of societies

throughout history — mainly because it has been

essential for cooperation and collective action.

One of the purported paradoxes around trust

relates to there being higher trust than a rational

agent model where people pursue their self-interest

would suggest. Most economic theory assumes

that trust arises when people are optimistic about

the trustworthiness of others, but evidence shows

that people trust at higher rates than predicted

by reasons to be trustworthy (including past

behaviour). This excess trust seems to be driven by

norms — either social or moral.

2

This result provides

reason for optimism: this excess trust could be a

lever for increased cooperation among strangers

and beyond the close ties usually associated with

reciprocal relationships.

The result has been reflected, for instance, in

the voluntary payment of taxes. In 1972 Michael

Allingham and Agnar Sandmo modelled tax evasion

under a standard rational utility maximization

framework where the agent conducts a cost-benefit

calculation between the cost of being caught

evading tax systems and the monetary benefit of

the evasion.

3

But empirical evidence has shown that

the model consistently underestimates the amount

of taxes people pay. This paradox has promoted the

literature on tax morale — or the reasons beyond

pure rational maximization of self-interest driving

people to comply with the tax authorities.

Trust has been important both in interpersonal

relations and in institution building. Institutional

evolution is closely linked to trust in at least two ways,

as Benjamin Ho explains. First is that institutions rely

on trust to function — modern money, for instance,

depends on the belief that it will be accepted as a

medium of exchange regularly and independent

of who carries it. The second is that institutions are

often designed to create and facilitate trust, in ever

expanding scales of complexity.

4

Not all trust is good, though, and institutional

development has been imperfect across time and

countries. Some institutions have been designed

to expand trust among groups sharing similar

traits — known as in-group trust. In-group trust can

thus promote polarization, be detrimental to equity

and democracy and be exploited by some political

leaders.

5

The challenge when promoting trust in the

context of human security strategies is to promote,

support and use existing generalized trust and

address the behavioural biases and institutional

designs that favour in-group trust. Cosmopolitan

views and moral universalism — altruism towards

strangers compared with altruism towards in-group

members — may be invoked when designing and

implementing strategies to advance human security,

as elaborated later in the chapter. Some evidence

shows that universalist views are associated

with demographic characteristics: age, place of

residence, religious beliefs and income level.

6

Yet a

recent study by the United Nations Children’s Fund

and Gallup shows that young people are almost

twice as likely as older people to declare their

identification with the world as opposed to local or

national community.

7

Notes

1.2.Dunning and others

2014. 3.Allingam and Sandmo 1972. 4.Ho 2021. 5.Gjoneska and

others 2019. 6. Enke, Rodriguez-Padilla and Zimmermann 2021.

7.UNICEF and Gallup 2021.

19

in dealing with people?” The answer appears to con-

form to actual behaviour when people interact with

others.

It captures what has been characterized as

generalized trust (the trust placed in others in general

and not for a particular reason or interest

) or imper-

sonal trust (establishing a default way of interacting

with strangers

).

Understood in this way, it is clear that social life,

in any context, would be very dicult, if not impos-

sible, without impersonal trust.

Trust matters be-

cause it enables cooperation, which “is conditional

on the belief that the other party is not a sucker (is not

disposed to grant trust blindly), but also on the belief

that the other will be well disposed towards us if we

make the right move.”

Therefore, trust is not some-

thing that should always be maximized: even for in-

dividual welfare too much or too little trust is shown

to be harmful.

And we may want less trust among

groups that are threatening us (when engaged in illicit

activities, for instance), so it is not possible to say that

more trust is always desirable.

Given the importance of trust for cooperation, dif-

ferences in impersonal trust across countries are as-

sociated with several economic and social outcomes.

Higher average impersonal trust for countries is posi-

tively correlated with income, economic productivity

and government eectiveness and negatively correlat-

ed with corruption. Evidence suggests that impersonal

trust is part of a cultural and psychological package of

pro-social norms, expectations and motivations that

are historical antecedents of these outcomes.

This cross-country analysis needs to be interpret-

ed carefully, for trust increases when individuals are

socially closer.

And the answer to the World Values

Survey question in some contexts — particularly in

East Asia — is interpreted as trusting others premised

on the existence of dense social networks that create

social and economic interdependence, as opposed

to trusting “strangers” unconditionally. More impor-

tant, there are very large dierences in trust within

countries, even larger than across countries.

Factors

associated with individual preference “types” (being

more or less altruistic, for instance) appear to account

for a large amount of variation in trust across people,

more than can be explained by the country where

people live.

In this context it is crucial to emphasize

again that the ndings of an association between high

human insecurity and low interpersonal trust are at

the level of individuals — not based on a cross-country

analysis.

The individual-level association between human

insecurity and impersonal trust matters for four main

reasons.

• First, evidence suggests that there are low and

declining levels of trust related to important in-

stitutions and policy outcomes, especially those

predicated on cooperation.

• Second, while motives, interests and incentives

are crucial for cooperation, even if people (or

countries) have the appropriate motives and inter-

ests, they still need to “know about each other’s

motives and trust each other”

— this takes us back

to Kaushik Basu’s emphasis on the importance of

beliefs noted earlier in the chapter — even if laws

are codied and enforced.

“

A human- development- with- human- insecurity

duality emerges from how the advancement of

human development has been pursued and from

fragmented security approaches that focus on

wellbeing achievements while neglecting agency

• Third, as this chapter develops later, agency is

central to implementing strategies to advance

human security. It is predicated on people having

freedoms, which include the possibility of disap-

pointing and frustrating others. That is why trust is

closely associated with freedom, having even been

described as a “device for coping with the freedom

of others,”

something that acquires heightened

relevance in contexts of uncertainty.

• Fourth, the importance of trust is likely to increase

in coming years, given that “in the twenty-rst

century, remote collaboration with both unknown

and known counterparts is increasing (in part due

to the recent pandemic), and much economic life is

now happening outside the boundaries of organiza-

tions, regions, and nations, making trust a ubiqui-

tous concern.”

Reasons to feel insecure: The Anthropocene context

and a new generation of threats to human security

This section argues that a human- development- with-

human- insecurity duality emerges from how the

20 NEW THREATS TO HUMAN SECURITY IN THE ANTHROPOCENE / 2022

advancement of human development has been pur-

sued and from fragmented security approaches that

focus on wellbeing achievements while neglecting

agency. Along with a persistent upward trend in well-

being achievements across regions, a new generation

of human insecurities has been emerging, to a signi-

cant degree as a byproduct of how development was

being pursued. This is evident from the emergence

of the Anthropocene context, in which new threats

to human security emerge, all linked to human ac-

tion and, for the most part, to activities that have until

now fuelled improvements in wellbeing.

The unprecedented context of the Anthropocene

is the backdrop for a new generation of threats that

are global, systemic and interlinked. This new reali-

ty gives strong objective reasons for people not only

to perceive high human insecurity but also to believe

that wellbeing achievements — previously conceived

of as development achievements — are insucient to

address human security concerns. This section high-

lights threats related to digital technologies (though

much good can also come out of their diusion), vi-

olent conict, inequalities across groups (to focus

on the notion of social imbalance) and inadequacies

in current healthcare systems. All these exhibit new

characteristics compared with what was covered in

previous seminal reports on human security, nota-

bly the 1994 Human Development Report and the

2003 Ogata-Sen report,

but are not meant to be an

exhaustive list. Rather than organize the discussion

around groups of people, the focus is on these four

threats, as elaborated in part II of the Report, be-

cause this approach allows for a more exible under-

standing of the structural challenges and the possible

structural responses (gure 1.5).

“

Ensuring that people live free from want,

fear and indignity requires a comprehensive,

systemic approach. We have come to realize

that higher incomes, for instance, do not

automatically bring about peace and that a

society without violent conict is not a sucient

condition for people to live in dignity

These four threats, in their interconnectedness,

present a growing challenge for decisionmakers, for

the development journeys unfolding have often un-

derplayed not only agency but also the interactions

across threats. The attention of the public and pol-

icymakers has been on separate aspects when de-

signing or evaluating policy, leading to the pursuit of

solutions to problems in silos, failing to recognize the

possibility that each solution may have unintended

consequences and may exacerbate other problems.

To address this challenge, the relevance of the

human security concept becomes apparent in part

because one of the most important aspects empha-

sized since its inception is the recognition that the

three aspirations that dene it cannot be thought of

independently, as noted above.

Ensuring that peo-

ple live free from want, fear and indignity requires a

comprehensive, systemic approach. We have come to

realize that higher incomes, for instance, do not auto-

matically bring about peace and that a society with-

out violent conict is not a sucient condition for

people to live in dignity.

As Oscar Gomez and Des

Gasper write, “Even a human development perspec-

tive, focused on improvement for persons in all major

areas of life which they have good reason to value,

rather than centred on measured economic growth or

technological display, is insucient for dealing with

Figure 1.5 A new generation of threats to human security

is playing out in the unprecedented context of the

Anthropocene

Source: Human Development Report Office.

Digital

technology

threats

Health

threats

Inequalities

Violent

conflict

Other

threats

A

n

t

h

r

o

p

o

c

e

n

e

c

o

n

t

e

x

t

21

the real world of interconnecting threats and recur-

rent crises, if it retains the linear model.”

One could argue that everything has always been

connected to everything else, but the Anthropocene

context heightens the importance of recognizing

these interdependencies. Virtually all people’s eorts

to nd solutions to development problems result in

actions that are mounting planetary pressures in one

way or another.

The 2020 Human Development

Report argued that industrial societies today meet

their energy and material needs in ways that result in

planetary pressures that drive dangerous planetary

change.

To meet our energy needs, we continue to

rely primarily on fossil fuels, which results in green-

house gas emissions that are driving climate change.

And we use materials with little concern for the dis-

ruptions to material cycles: the use of nitrogen in fer-

tilizer is just one example. For an illustration of how

the solving-one-problem-at-a-time approach may be

problematic, consider how the increased use of re-

newable energy and batteries is leading to increased

extraction of minerals that we know are limited and

for which we have few substitutes at present, often in

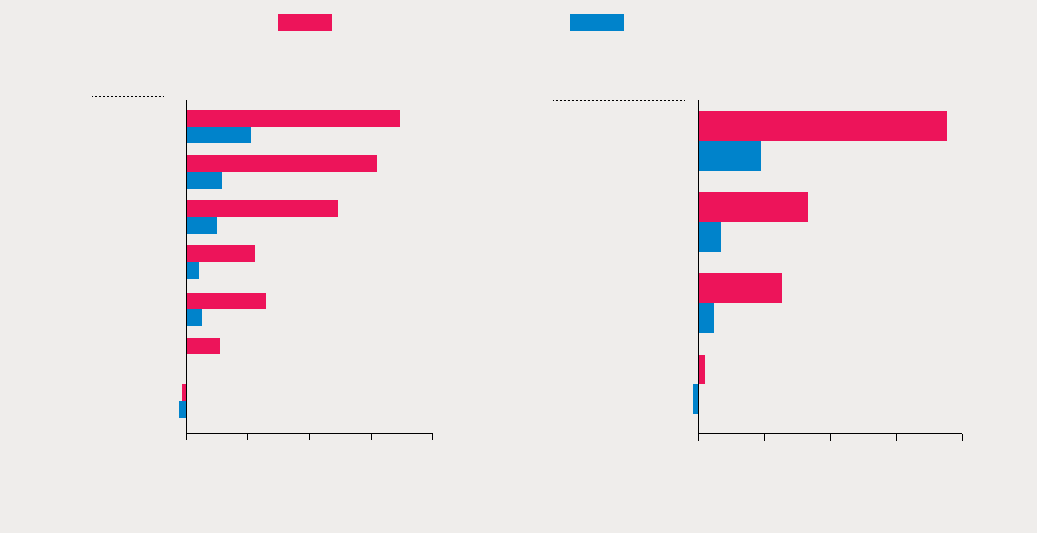

contexts where there are massive threats to biodiver-

sity and violations of human rights.

As countries have increased their Human Devel-

opment Index value, planetary pressures have inten-

sied, on average, as measured by a new index of

planetary pressures (gure 1.6). This index combines

two indicators, carbon dioxide emissions (to account

for the pressures emanating from the reliance on fos-

sil fuels for energy) and material footprint (to indicate

the extent to which we do not consider the disrup-

tion to material cycles). No country has been able to

reach a very high HDI value without exerting high

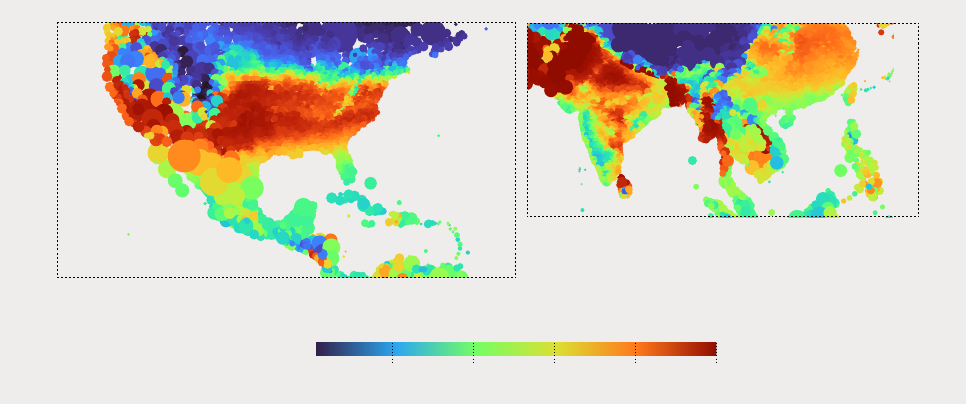

planetary pressures. These pressures are now causing